Summary by Stephen Ross, MD

90

Based on “Principles of Addiction Medicine” Chapter by Stephen Ross, MD, Jeffrey R. Guss, MD, and Erin Zerbo, MD

INTRODUCTION

Personality disorders (PDs) are defined by DSM-IV-TR as “enduring patterns of inner experience and behavior” that are deep-seated, inflexible, and at odds with cultural norms and expectations and produce psychopathologic symptoms affecting cognition, emotion, interpersonal functioning, and impulse regulation. The patterns cause repeated conflicts with one’s social and occupational environment and lead to emotional distress, while the individual usually experiences the disorder as ego-syntonic and externalizes blame for his or her dysfunction. The onset of diagnosable PDs occurs in late adolescence or early adulthood when personaltiy trait patterns become stable. Although PDs tend to have a chronic course of illness, longitudinal studies have generally supported the notion that PDs tend to improve over time from the perspective of decreases in clinical symptomatology, although the evidence is more mixed for cluster A and C disorders.

PDs and substance use disorders (SUDs) are highly associated with each other, especially in mental health and substance abuse treatment settings where these represent the norm in terms of comorbidity. Screening and the use of standardized assessment instruments are vital components of diagnostic formulation to determine the presence of a PD that is distinguishable from or co-occurring with an SUD. Given the epidemiologic data where the majority of patients with a PD have a co-occurring addictive disorder and vice versa, an a priori assumption diagnostically should be that there are two separate problems until proven otherwise. Patients with co-occurring SUDs and PDs can benefit from treatment as much as those without PDs, but the presence of a PD does negatively affect the course of treatment of the addictive disorder and is associated with worse outcomes. It is important to provide comprehensive care, optimally within a structured environment with a dual focus (i.e., PD and SUD), utilizing integrated psychosocial treatments for PDs and SUDs, in an integrated system of care, and providing symptom-targeted pharmacotherapy when appropriate as an adjunct to psychosocial interventions. This chapter reviews the following regarding PDs and co-occurring SUDs: Definitions/Classification Systems, Epidemiology, Diagnostic Assessment, and Treatment.

DEFINITIONS/CLASSIFICATION: CHANGES FROM DSM-IV TO DSM-V PD CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

The DSM-IV classification system for PDs was based on phenomenology and clinical observation and has been criticized as leading to high comorbidity between Axis II PDs, vaguely defining core commonalities among PDs, and not accounting for level of personality dysfunction or the complexity and individual manifestations of personality psychopathology. To address these shortcomings, DSM-V has proposed a new classification system, considered a “hybrid” categorical–dimensional system that includes (1) common diagnostic criteria: impairments in self (identify vs. self direction) versus interpersonal (intimacy or empathy); (2) five levels of personality function that account for severity variability and generate 60 possible combinations of self versus interpersonal functioning; (3) a dimensional system with five domains (negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, psychoticism) comprising 25 pathologic personality traits; and (4) a categorical system with 6 of the 10 DSM-IV diagnoses (schizotypal, borderline, narcissistic, antisocial, avoidance, obsessive– compulsive) remaining although the methodology to diagnose them will be changed relative to DSM-IV.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PDs and SUDs are both prevalent in the general population. In looking at five well-designed (i.e., use of DSM-IIIR, DSM-IV, or ICD-10 diagnostic criteria and structured or semistructured interviews) community surveys of PDs published since 2000 with sample sizes ranging from 214 (NCS-R) to 43,093, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Condition (NESARC), the estimated prevalence of any PD in the general population ranged from 4.4% to 13.4% with a median of 9.6% and with cluster C disorders (obsessive compulsive personality disorder [OCPD] and avoidant PD) being the most commonly diagnosed. In comparison, SUDs, defined as either substance abuse or dependence, affect approximately 22.6 million (9.2% of the population) individuals 12 years of age or older, including both alcohol or illicit drugs. This does not include nicotine use disorders, which affect approximately 21% of the population.

In addition to both being prevalent conditions by themselves in the general population, PDs and SUDs are intimately related in community samples. For instance, in a nonpatient sample of approximately 800 individuals who were relatives of both normal and psychiatric patients, of those who had any PD, 43% and 53%, respectively, met criteria for a lifetime AUD or DUD, and having a PD increased the risk of both AUD and DUD by a factor of 4 compared to individuals without a PD. Using revised diagnostic criteria from the NESARC community sample, Trull and colleagues found that each PD was strongly associated with lifetime dependence syndromes with the highest rates of co-occurrence as follows: alcohol dependence co-occurring with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), and histrionic PD, all at approximately 50%; drug dependence co-occurring with histrionic PD 29%, dependent PD 27%, and ASPD approximately 25%; and nicotine dependence co-occurring with ASPD, BPD, and dependent PD, all at approximately 50%.

Compared to the rates of PDs in community samples, the rates of PDs in psychiatric and SUD are significantly increased. In selecting well-designed studies (i.e., random selection, sample size ≥100, use of standardized diagnostic instruments), Verheul reported on the prevalence rates of Axis II psychopathology: 45% to 80% (median 60%) in psychiatric patients and 35% to 73% (median 57%) in patients treated for SUDs.

Even though cluster C diagnoses (OCPD, avoidant PD) are the most common PD diagnoses in the general population, cluster B disorders (ASPD and BPD) are the most commonly associated with SUDs either in community or treatment (substance abuse or psychiatric) samples. In a review of comorbidity data between BPD and SUD, Trull et al. reported that among those seeking addiction treatments, rates of BPD ranged from 5% to 65% and conversely, among those receiving treatment for BPD, the prevalence of current SUDs is between 25% and 67%. From the ECA study, ASPD (among men) was more frequently diagnosed with an SUD than any other Axis I or II disorder with 83% of individuals with ASPD also meeting criteria for an SUD and with ASPD being diagnosed in 18% of those with a DUD and 14% with an AUD.

DIAGNOSIS: PRACTICAL ISSUES

Screening is a crucial step prior to diagnostic formulation. Since patients with PDs tend to have more severe pathology and more frequent treatment contact, they are more likely to present in the situations with the least time for assessment, such as emergency rooms or incarcerated settings. However, most screening questionnaires focus on specific PDs or require too much time to be used in routine clinical practice. To remedy this, Cloninger has proposed a 20-item screen that focuses on four core features that are suggestive of any PD: low self-directedness, low cooperativeness, low affective stability, and low self-transcendence (the last encompassing unstable self-image, emptiness, and erratic world view). Clinicians can keep these features in mind as “red flags” for the need to pursue more thorough PD assessment.

The use of standardized assessment instruments is important in diagnosing PDs because traditional unstructured clinical diagnostic interviews are poorly reliable and are associated with missed and incorrect diagnoses. There are a number of formal assessment tools used in evaluating personality pathology, although these were not specifically designed for an SUD population.

Any assessment tool must be considered along with other information sources, such as unstructured patient interview, collateral information, and longitudinal assessment. Collateral contacts can be helpful in elucidating long-standing behavior patterns, can provide information that the patient is not able or willing to provide, and can increase the convergent validity of diagnoses. Risk assessment for suicidality, self-injury, and violence deserves special attention, especially in patients with BPD and ASPD. Given the high-risk nature of these patients, a team-based approach and access to referral services is ideal for optimal management.

In addition to a careful substance history and risk assessment, important areas of focus include a history of trauma (abuse, neglect, conflict in the household), familial history of personality dysfunction, and quality/quantity of current and past interpersonal relationships. Inflexible or maladaptive coping skills are the hallmark of a PD. Close attention to interpersonal style and transference/countertransference can yield important diagnostic information. For example, patients with BPD tend to develop transference quickly and intensely and to have extreme and rapid oscillations (the clinician is experienced as all good and ideal, and then suddenly all bad and malicious after a seemingly small disappointment). Schizoid or avoidant patients may be especially deferential or reserved in a clinical encounter. It is also important to rule out other co-occurring Axis I disorders whose symptom presentation may mimic symptoms of various PDs. For example, bipolar I or II disorder should be excluded before diagnosing borderline PD, and social phobia should be ruled out before diagnosing avoidant PD. A detailed temporal history and longitudinal observation and assessment is key to differentiate acute state phenomenon usually associated with Axis I disorders (i.e., acute mood instability associated with mania) versus longer-term traits associated with PDs.

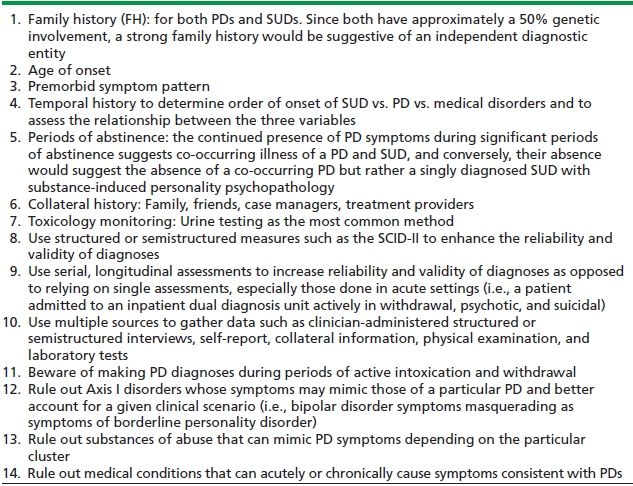

The ultimate goal of assessment is to determine the presence of a PD that is distinguishable from or co-occurring with an SUD. Several factors can help in this process (Table 90-1). Given the epidemiologic data where the majority of patients with a PD (especially BPD and ASPD) have a co-occurring addictive disorders and vice versa, an a priori assumption diagnostically should be that there are two separate problems until proven otherwise by a process of exclusion (i.e., that it is a case of an etiologic diagnosis). As a general clinical rule, symptoms that persist beyond 1 month of abstinence are more likely to be primary. It is further important to assess substances of abuse and medical conditions that can occasion symptoms that mimic those of PDs or exacerbate them.

TABLE 90-1. DIAGNOSTIC FORMULATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree