Frances Rudnick Levin, MD, and John J. Mariani, MD

89

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF ADHD AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is highly prevalent in child and adolescent populations, with rates ranging from 8% to 18%. The adult rate of ADHD is estimated to be from 2.5% to 4%. There is strong evidence that substance use disorders (SUDs) are more common among adults with ADHD, with rates two to three times than found in the general population. Similarly, ADHD is overrepresented among SUD individuals in the general population and those seeking treatment for their SUD. Numerous studies, both in the United States and throughout the world, have found that the rate of adult ADHD ranges from 5% to 33%. Similarly, SUDs appear to be overrepresented in adults with ADHD, whether or not they are seeking treatment, roughly three times as likely as those without ADHD to have an SUD. Individuals with ADHD also have a greater likelihood of nicotine dependence.

UTILITY OF ADHD SCREENING INSTRUMENTS IN SUBSTANCE-ABUSING POPULATIONS

Three commonly used instruments include the Wender Utah Rating Scale, which screens for childhood ADHD; the Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale, and Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale. Each of these screens has been used in the general and treatment populations with good results, although the applicability to SUD patients is less well studied.

THE IMPACT OF HAVING ADHD ALONE AND WITH SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

ADHD has substantial morbidity in and of itself. Children with ADHD who are followed into adulthood are more likely to have completed less schooling, to hold occupations with less professional or social status, to suffer from poor self-esteem, to have social skill deficits, and to have antisocial personality disorder. As adults, individuals who are diagnosed with ADHD in childhood are more likely to have had their driver’s licenses suspended, to incur speeding violations, to have quit or been fired from a job, and to have been married multiple times. ADHD symptoms appear to place these individuals at great risk for antisocial personality disorder, mood and anxiety disorders, and substance abuse. Women with ADHD may be particularly vulnerable to eating disorders, such as bulimia. Moreover, persistent symptoms seem to place individuals at greatest risk for early substance use.

When ADHD symptoms are combined with those of a SUD, the severity of impairment of each disorder is likely to increase, and the individual’s response to addiction treatment is adversely affected by comorbid ADHD. Since ADHD may exert a negative effect on the course of a SUD, treatment needs to be targeted at both the psychiatric and SUDs.

POSSIBLE REASONS FOR LINKAGE OF ADHD AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Various explanations have been offered for the link between ADHD and SUD, including (1) the presence of a necessary mediating factor, such as conduct disorder, (2) the persistence of ADHD symptoms, (3) self-medication, (4) genetic factors, and (5) exposure to stimulants in childhood. Prospective studies that have followed children with ADHD into adolescence suggest that a mediating factor—specifically, conduct disorder—substantially increases the likelihood of an SUD diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS OF ADHD

ADHD is characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. To meet DSM-V criteria for ADHD, individuals must have (1) six symptoms of inattention (inattentive type) (five symptoms if an older adolescent, age 17, or older or adults), (2) six symptoms of impulsivity and hyperactivity (impulsive/hyperactive type) (five symptoms if an older adolescent, age 17, or older or adults), or (3) both (combined type). Some ADHD symptoms need to be present prior to the age of 12, some impairment from these symptoms need to be present in two or more settings, and the symptoms must produce clear evidence of interference with and reduction of the quality of social, academic, or occupational functioning. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis that is best made by carrying out a comprehensive assessment that includes developmental history, learning history, evaluation of other psychiatric comorbidities, and medical evaluation. An issue that complicates assessment and often leads to diagnostic confusion is that of additional psychiatric comorbidity. Generally, because ADHD symptoms are present in elementary school and precede the SUD, ADHD can be more readily identified as an independent disorder, compared with disorders that usually are episodic in nature and may occur only after regular substance use has developed.

TREATMENT OF CO-OCCURRING ADHD AND SUD

Patients with co-occurring ADHD and SUD present a formidable challenge for any clinician treating such individuals. Compared with other patients with SUDs, individuals with ADHD may have greater difficulties in processing information and in sitting through group meetings—a common format for addiction treatment. Because individuals with ADHD have a tendency to act impulsively, they also may be more likely than those without ADHD to drop out of treatment.

PHARMACOTHERAPEUTIC OPTIONS FOR THE TREATMENT OF ADHD

Amphetamine analogs and methylphenidate have been the most widely studied pharmacotherapies for adult ADHD, although nonstimulant medications, including atomoxetine, tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), alpha-2 agonists, venlafaxine, and the novel stimulant modafinil, have been studied as well. While there is substantial evidence for the efficacy of these agents in adults with ADHD, there are only a limited number of studies of patients with co-occurring ADHD and SUD.

Stimulant Medications

Amphetamine analogs and methylphenidate are the stimulant medications most commonly used to treat ADHD in children and adults in the United States. Side effects most commonly associated with amphetamine and methylphenidate administration include insomnia, emotional lability, nausea/vomiting, nervousness, palpitations, elevated blood pressure, and rapid heart rate. Rare but serious adverse effects include severe hypertension, seizures, psychosis, and myocardial infarction.

Nonmedical Use/Misuse and Abuse Potential of Psychostimulants

While methylphenidate and amphetamine analogs are widely used in the treatment of ADHD, concern exists with respect to their abuse potential, particularly in patients with SUD. Individuals who receive medication for ADHD are twice as likely to be asked to divert their medication as are those receiving medications for pain, sleep, or anxiety. Long-acting preparations may have lower abuse potential and may have particular utility for patients with co-occurring SUD. An additional advantage of delayed-release preparations is greater difficult to using via a nonoral route (e.g., injected or intranasally), which should also reduce the potential for misuse and diversion. It is crucial that patients who are prescribed stimulants for their ADHD, regardless of whether they have a concurrent SUD or not, be warned about the risks associated with prescription stimulant use, understand why it is important not to “share” their medication with others, and be given strategies of how to safeguard their medication so that it is not diverted.

Nonstimulant Medications

A diverse group of nonstimulant medications has been identified as having some efficacy for the treatment of ADHD, although none has been shown to be therapeutically equivalent to stimulant medications. With the exception of atomoxetine (which is FDA approved for pediatric and adult use) and guanfacine-extended release (which is FDA approved for pediatric use), all other nonstimulant medications are “off-label” for ADHD and are generally considered second- or third-line treatments. There are certain instances where nonstimulant medications would be considered first line, such as if a motor tic disorder is present or in the case of cardiovascular disease. It remains controversial whether the presence of even an active SUD represents such a significant risk that the superior efficacy of stimulant medications should be traded off for the lower abuse potential of nonstimulant medications. Atomoxetine is a centrally acting noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor. Common side effects of atomoxetine include sedation, appetite suppression, nausea, vomiting, and headache. Rare but serious side effects reported in children and adolescents include increased suicidal ideation and hepatotoxicity. Guanfacine extended release, an alpha-2 agonist, has been shown to be nearly as effective as stimulants in youth, and although it has not been as extensively studied in adults, there is evidence that it is effective in treating adult ADHD symptoms as well. Common side effects of guanfacine include somnolence, headaches, sedation, and blood pressure decreases.

A number of antidepressant agents have been studied for the treatment of ADHD. Tricyclic antidepressants, which block the reuptake of norepinephrine, have some efficacy in reducing ADHD symptoms but are considered to be less effective than the stimulant medications. The dopaminergic antidepressant bupropion has been reported to be effective in the treatment of ADHD, although when studied in patients with SUD, it offered no benefit over placebo. Venlafaxine, a norepinephrine–serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant medication, has limited evidence of efficacy in ADHD in uncontrolled clinical trials. MAOIs have been shown to have efficacy for ADHD, but the potential for hypertensive crises associated with tyramine-containing foods and medications (both illicit and prescribed) limits their utility, and MAOIs should be considered contraindicated in patients with SUD.

Clonidine, a noradrenergic alpha-2 agonist antihypertensive agent, has been shown to be effective for the treatment of ADHD although less so than stimulant and other FDA-approved nonstimulant medication. Side effects include sedation, dry mouth, depression, confusion, electrocardiographic changes, and hypertension with abrupt withdrawal. Modafinil has been shown to improve ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents, albeit less so. Modafinil has minimal reported abuse potential and has not been shown to be as effective as traditional stimulant medications.

PHARMACOTHERAPY SELECTION FOR ADHD AND CO-OCCURRING SUD

At present, there are no clear-cut guidelines regarding the appropriate use of traditional stimulant medications, methylphenidate and amphetamine analogs, in the treatment of adult ADHD and SUD. To our knowledge, there have been 10 medication outpatient double-blind treatment studies conducted in active SUD with ADHD in which only 4 evaluated a nonstimulant medication. None of the nonstimulant trials found the medication (bupropion or atomoxetine) to be superior to placebo in reducing substance use on the primary outcome measures. However, atomoxetine was found to be superior to placebo in treating ADHD in alcohol-dependent individuals and outperformed the placebo group on some secondary alcohol outcome measures. The therapeutic use of stimulant medications has been studied in patients with co-occurring adult ADHD and SUD, with mixed reports of efficacy. In none of the trials using stimulants was abuse or misuse of prescribed stimulant medication reported.

Further evidence of the feasibility of using stimulant medications for the treatment of co-occurring ADHD and SUD can be found in the literature describing the use of stimulant treatment of cocaine dependence. The results of these studies have been mixed with regard to effects on cocaine use outcomes, with the most consistent positive effects reported for dextroamphetamine. A sustained release of methamphetamine, an amphetamine analog, has also been evaluated for cocaine dependence and was associated with lower rates of cocaine-positive urine samples and greater reduction in craving than placebo, while the immediate-release formulation of methamphetamine was not superior to placebo for cocaine use outcomes.

Despite concerns that prescription stimulant use may lead to increased craving and cocaine or amphetamine use, this effect has not been reported in the controlled clinical trials conducted to date. While prescription stimulant medications may be diverted for nonmedical use, clinical data suggest that the use of stimulants in a structured therapeutic context can be accomplished safely.

Taken together, the clinical trials have shown some “signal” in that the active medication performed better than placebo in reducing ADHD symptoms and about half showed greater substance use reduction on medication if there were an ADHD response. However, overall, this response has been modest. Some possible reasons for the modest response to medications for substance abusers with ADHD include (1) inadequate dosing; (2) less responsiveness if actively using substances; (3) lack of abstinence to clarify the ADHD diagnosis; (4) use of older, poorly absorbed sustained-release stimulant formulations; (5) additional comorbidities; and (6) poor compliance.

In choosing between stimulant and nonstimulant agents for co-occurring ADHD and SUD is balancing the risk of untreated ADHD symptoms versus the risk of stimulant misuse and diversion. In developing a treatment plan for co-occurring ADHD and SUD, these risks must be considered in light of the individual characteristics of the patient in question. The appropriateness of the medication choice should be regularly reassessed based on the patient’s clinical response and overall clinical status. General recommendations for pharmacotherapy management of ADHD and co-occurring SUD follow.

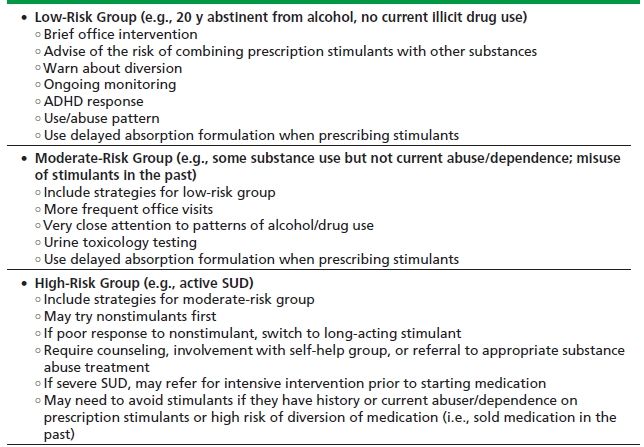

To help organize treatment planning decision making, we propose classifying patients with co-occurring ADHD and SUD into three risk groups: low, moderate, and severe (Table 89-1). The most important clinical variable in considering the use of stimulant medication is whether the SUD is active or in remission. Patients with a remote history of an SUD and a long period of abstinence from substance use likely represent a low-risk group for prescribing stimulant medications. Patients should be counseled that their history of SUD may put them at increased risk and general prescribing precautions should be employed (e.g., use of delayed-release preparations, monitoring prescription renewal times, surveillance for evidence of substance use).

TABLE 89-1. SUGGESTED TREATMENT STRATIFICATION FOR CO-OCCURRING ADHD/SUD

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree