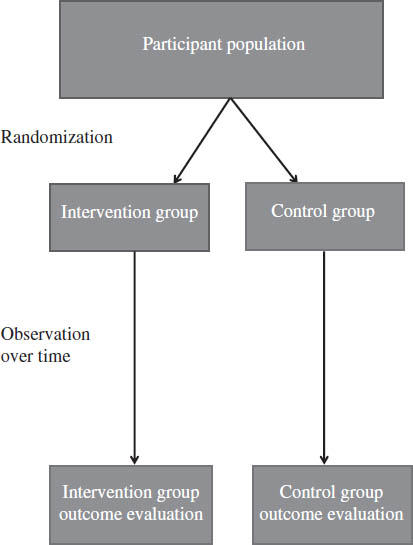

Figure 11-1. Example of Parallel Design

Figure 11-2. Example of Crossover Design

a. May include washout period.

Key Aspects of Randomized Controlled Trials

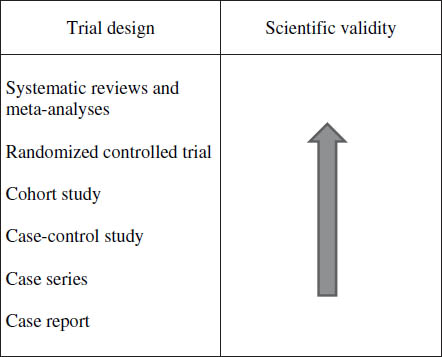

RCTs have a high weighting in the ranks of medical literature. See Figure 11-3 for a diagram illustrating general considerations regarding scientific rigor of particular study designs. Understanding the basics of RCT design will aid in interpreting the results and applying new literature to study practice. This section reviews key considerations of RCT design. Many of the principles covered here may also be applied to other types of trials.

Sampling and randomization

Sampling of a population is necessary in RCTs because enrolling every patient within a population with a particular disease state or condition in the study is not feasible. Key aspects of sampling are as follows:

■ Study participants must be representative of the population to which the results of the study are to be applied.

■ Patients enrolled in the study must meet all of the predetermined study inclusion criteria, and conversely, they must not have any of the characteristics listed as exclusion criteria.

Figure 11-3. Hierarchy of Literature Evidence

Clinicians should consider the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria when applying the study results to avoid extrapolating these results to patients who may not be representative of the population being evaluated. Alternatively, one can infer that similar findings will be observed in other patients who meet these criteria within the probabilities emanating from inferential statistics used to analyze the study data. One of the basic principles of inferential statistics is that patients sampled from a particular population of interest have an equal chance of being randomized or assigned to one of the study groups or another. As such, systematic error can occur when study participants are not properly randomized into the study groups, which can lead to potentially misleading and incorrectly interpreted study results because of bias in patients being assigned to one group or another. Randomization does not ensure that study participant characteristics (e.g., sex, weight, race, and so on) are equally divided between study groups. A process known as stratification can be used to accomplish the latter. Stratification is a grouping that occurs before randomization, although grouping of patient characteristics can be performed retrospectively. In this latter instance, the process is often referred to as subgroup analysis.

Blinding

In clinical trials, blinding refers to the process whereby some or all of the participants are unaware of the treatment being received by the study participants. Blinding is a very important strategy for decreasing bias within any clinical trial. The underlying purpose of blinding is that study volunteers or patients may knowingly or unknowingly alter the study outcome data if they know which treatment or treatments they are receiving. Similarly, study investigators may bias data collection based on the perceived benefits of the treatment or lack of benefits they are observing if they are aware of the treatment the volunteers or patients are receiving or not receiving, respectively. Nevertheless, certain clinical studies may not be suitable for blinding because of safety or ethical concerns (e.g., administration of investigational treatments through compassionate use protocols, severely ill patients, and so on). Regardless of blinding type, the processes must be in place to break the blind if needed for safety reasons. When no blinding is used, studies are referred to as open-label trials. Generally accepted blinding definitions are as follows:

■ Single blind: Patients are unaware of which treatment they are receiving.

■ Double blind: Neither the study patients nor the investigators are aware of the treatments. This is the traditional gold standard within clinical research focused on treatment efficacy because this design has the greatest potential for minimizing bias from the study participants and investigators.

■ Triple blind: All persons coming in contact with the study procedures or data (e.g., during the data analysis phase) are unaware of the study treatments in addition to the study participants and investigators.

Maintaining study blinding can be very challenging or virtually impossible irrespective of careful study planning and design. Such challenges can be overcome to some extent by using a group of blinded investigators—independent of those unblinded investigators or personnel directly interacting with the study participants—to gather the safety and efficacy data. Regardless of the blinding strategies used, investigators should provide details, to the greatest extent possible, on their maintenance of blinding for any trials published in medical literature.

Sample size

Selection of sample size is an extremely important issue in designing randomized clinical trials. Inadequate numbers of study participants will decrease the statistical power of any clinical trial. In this instance, patient numbers may be insufficient to report a statistically significant difference between the study treatments, although in actuality a difference does exist. Thus, statistical power is the probability of avoiding a false negative study result. Conversely, recruitment of an excessive number of study participants may be very inefficient despite being more than adequately powered statistically. Specifically, patient recruitment may take much longer than is necessary as well as substantially increase the study budget, thereby making the study unfeasible to conduct. Generally, the greater the expected difference between the study treatments, the fewer the number of study participants that will be needed to demonstrate a statistically significant difference between the groups. Furthermore, fewer study participants will be needed when less variability exists in the study outcomes being measured from one participant to another. Statistical power can be calculated by investigators and bio-statisticians on the basis of estimates of the expected differences and variability between the study groups and should be included in any published report of the study results.

Controls

In the context of RCTs, controls are the comparator to the treatment of interest. In a crossover study design, patients serve as their own control. As previously noted, control groups may receive standard treatments, no treatment, usual care, or placebos in both RCT crossover and parallel designs. Ideally, the placebo should have dosage form properties (e.g., color, shape, taste, and so on) that are identical to the active treatment dosage forms to avoid compromising study blinding. The potential for a “placebo effect” should always be considered. This occurs when the placebo has an effect on the study outcome despite receipt of an inactive substance. Use of placebos may not be suitable for all RCTs because of ethical considerations. In these instances, an active or usual treatment would be used as the control.

Follow-up

Any RCT must follow the study participants over a sufficient period of time to demonstrate adequate safety or efficacy data or both. The length of follow-up is determined by the following:

■ The period of time intended for patients to receive the study intervention

■ Long-term safety concerns

■ The study objectives and outcome measures (e.g., pain scale, overall survival, and so on)

During the treatment and follow-up study periods, not all participants may remain in the study. More specifically, participants may drop out of the trial. This can occur for a number of reasons, and investigators must plan how to handle the partial data in addition to the study sample size determination as previously noted. The two major analysis approaches are as follows:

■ Intention to treat: This method includes all patients as a member of their respective study group, regardless of completion of the protocol since they began the study and were randomized. Data up to the point of withdrawal are used in the analysis.

■ Per protocol: This method excludes data from participants with significant deviations from the protocol. If incomplete data are excluded from study outliers, this exclusion may increase precision and homogeneity of the study results. If incomplete data are related to adverse events or lack of response, this may bias results in a positive manner. For example, if many of the patients with adverse events withdraw from the study and are not included in the data analysis, then the treatment may appear to be safer than is actually the case. As such, dropout patient characteristics and reasons for study withdrawal should be included with reporting of the other study results.

Importantly, the two analytical techniques are not mutually exclusive. Often investigators will report results from both techniques that allow the reader of the report to compare potential differences directly. The following are additional sources for guidance in designing clinical research studies:

■ Spilker B. Guide to Clinical Trials. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1991.

■ Freidman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets DL. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 1998.

11-5. Principles of Evaluation for Medical Literature

Critical appraisal is an objective systematic review of medical literature. The critical appraisal of original research articles can be time consuming; however, the skills required are not difficult to develop and are highly important to pharmacy practitioners. Critical appraisal of the literature can be broken down into four steps:

■ Search the literature for relevant evidence.

■ Determine the applicability of the study.

■ Evaluate basic study design.

■ Critically evaluate the validity of the study results.

The following series of questions will aid in evaluating the design of a clinical trial and validity of the results. These questions were adapted from Guyatt, Sackett, and Cook (1994) and assembled by Hill and Spittlehouse (2001):

■ Did the trial address a focused research question in terms of the following?

• Population studied

• Intervention given

• Outcomes considered

■ Did the authors use the correct type of study design?

■ Was the assignment of participants randomized?

■ Were all of the participants who entered the trial appropriately accounted for as well as those not enrolled in the study?

■ Were participants and study personnel blinded? If not, were appropriate efforts made to blind the study treatments, or is there appropriate justification for not blinding?

■ Did the groups have similar baseline characteristics at the start of the study?

■ Aside from the experimental interventions, were the groups treated equally?

■ How large was the treatment effect?

■ How precise was the estimate of the treatment effect?

■ Can the study results be applied to the local population?

■ Were all clinically important outcomes considered?

■ Are the benefits worth the harm and costs?

The following are additional sources for guidance in assessing medical literature and the practice of evidence-based medicine:

■ Guyatt G, Drummond R, Meade MO, Cook DJ, eds. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidenced-Based Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill; 2008. Available at: http://www.jamaevidence.com/resource/520.

■ Greenhalgh T. How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine. London: BMJ Books; 2001.

11-6. Practical Implications of Primary Literature

Diligently reviewing and applying appropriate primary literature can aid in improving the care of patients. However, medical knowledge is not stagnant, and new investigations are continually refining and improving the treatment of patients. Thus, treatment based on old literature may no longer meet current standards of care, and clinicians need to review the literature regularly. The amount of new literature being published daily can easily overwhelm practitioners; hence, review articles, systematic reviews, and clinical practice guidelines play an important role in keeping practitioners up to date. The following steps can help practitioners deal with the fast pace of medical literature:

■ Identify three to five key journals that are relevant to your practice, and review them regularly for pertinent literature (monthly or bimonthly basis).

■ Regularly attend continuing education courses, and keep up with continuing education resources and requirements.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree