INTRODUCTORY CASES

CASE 6-1

GW is a 23-year-old female who is seen by her family medicine physician following several months of increasing fatigue and generally not feeling well. She reports she has lost 16 lbs over the past 6 months without dieting. She is applying to medical school and thinks this may be stress related.

CASE 6-2

RM is a 52-year-old male who presents to the emergency department with mild chest pain and shortness of breath. He reports that his symptoms began about 3 hours ago just before landing at the local airport after a 18-hour flight from Asia.

LABORATORY MEDICINE

Laboratory medicine will play a critical role in the workup of each of the above patients. The importance of the history and physical must not be understated, but the data often obtained from these activities are subjective or dependent on the patient and the stage of the condition. Furthermore, the signs and symptoms of many diseases are similar, so much so, that patients can be misdiagnosed or mismanaged without additional data. Consider, for example, the number of disorders that can cause the fatigue and weight loss reported by the patient in Case 6-1. Is the shortness of breath and chest pain reported in Case 6-2 due to a cardiac or respiratory problem?

As will be seen, the tests ordered by their respective clinicians and the results reported by the clinical laboratory will make the diagnosis in one patient and will greatly influence additional decisions for the other. These are but two examples in which the judicious use of clinical laboratory testing proves to be one of the most effective and economical ways of acquiring objective data that can clarify many presentations. Today’s clinician has several thousand individual tests at his or her disposal.

The goal of this chapter is to introduce you to laboratory medicine and the clinical laboratory thus removing some of the mystery of what happens when you order a laboratory test or take a sample to the laboratory, and to help you understand how to better use and evaluate laboratory tests so that you will be more efficient and effective in ordering tests and interpreting results.

WHAT WE DO

The use of this part of pathology, laboratory medicine (Figure 6-1), is so important to patient care that the clinical laboratories in these United States produce more than 7 billion test results each year that are used to derive a diagnosis, determine disease severity, assess risk factors, select and monitor interventions and treatments, formulate prognoses, and to evaluate or avoid potential adverse outcomes.

LABORATORY MEDICINE AND THE CLINICAL LABORATORY

Laboratory medicine is the part of pathology typically associated with the provision of laboratory test results. Traditionally, these tests were grouped according to the instruments and techniques used to perform the analyses, and the field is usually divided into the subdisciplines seen in Table 6-1. For example, glucose, electrolytes, enzymes, and proteins are measured using chemistry-based methods in clinical chemistry sections, while hormones are measured using antibody-based methods in immunology sections. As technologies have changed and evolved, these lines of distinction have blurred.

| Discipline or Section | General Role | Examples of Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Transfusion medicine (blood bank) | Collection, testing, processing, dispensing of blood and blood products for transfusion | Blood (ABO) typing, cross-matching |

| Clinical chemistry | Testing for a wide range of analytes from small ionic species and organic molecules to proteins, drugs, and hormones; includes toxicology, endocrinology, blood gases, and metabolic testing | Creatinine, sodium, potassium glucose, troponin, cholesterol, TSH, free thyroxin (free T4), drugs of abuse in urine, blood gases |

| Cytogenetics | Chromosomal analysis using fluids (blood, amniotic fluid, etc.), tissues and cells, uses techniques such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) | Karyotype (peripheral blood chromosome analysis), X/Y centromere analysis and subtelomere analysis |

| Hematology and coagulation | Identification and counting of blood cells | Complete blood count, differential, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT, PTT), factor VIII assay, fibrinogen antigen, sickle cell testing, identification of hemoglobinopathies |

| Immunology and histocompatibility | Testing related to the cellular and humoral immune function, uses techniques such as immunoassay and flow cytometry | Leukemia and lymphoma markers |

| Medical microscopy and urinalysis | Examination of body fluids other than blood using microscopic, physiochemical, and macroscopic techniques | Urinalysis, specific gravity, pH, crystal identification, ketones |

| Microbiology | Detection and identification of pathogens and infectious agents includes bacteriology, mycology, parasitology, and virology. | Hepatitis testing, HIV testing |

| Molecular diagnostics | Performs genetic testing at the gene and protein level | Factor V Leiden DNA, BRCA 1/2 gene mutations, Fragile X syndrome (FMR1 gene mutation), hemochromatosis, (HFE gene), CYP450 polymorphisms |

The professionals who work in laboratory medicine not only perform testing but also contribute to patient care through clinical service, education, research, and administration. They practice in a variety of settings from hospitals and medical schools, to private reference laboratories, in industry, and in government settings such as public health laboratories and federal and state regulatory agencies.

Today’s clinical laboratory is a busy place where you will find a range of professionals working together to produce test results. While pathologists and doctoral level clinical scientists are qualified to perform the analytical procedures, most generally do not engage in these activities, but instead provide testing oversight and administration. They work closely with the technical staff to determine what tests will be performed, to select the instrumentation and methods, and to assure appropriate quality practices are in place. These behind the scene roles are absolutely critical to patient care. As part of the clinical services they provide, these individuals guide other clinicians and providers in selecting the best or most appropriate test for the need, in interpreting the result, and in understanding the clinical performance and limitations of the tests. Who physically performs the analysis depends upon the complexity of the test method, a classification determined by the FDA.

A small, but growing portion of testing is performed by other health professionals such as nurses using small, portable devices often in the immediate patient setting. The latter is known as point of care testing (POCT) and even when performed by nonlaboratorians is often managed by the laboratory medicine department. Clinical testing is performed in other locations such as physician offices, free standing ambulatory centers, and in public health laboratories.

Regardless of the setting, any facility in the United States performing testing for patient care is regulated under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act of 1988 (CLIA) and its subsequent amendments. This includes all of the aforementioned settings outside of a clinical laboratory including physician offices. These regulations were established to assure accuracy, reliability, and timeliness of the test result used in patient care whether for health assessment or for the diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of disease. The regulations not only establish the various levels of testing based on the complexity of the method and instrumentation but also establish criteria for all levels of personnel, all phases of analytic testing, and quality assurance. The regulations mandated by this federal law are monitored by a variety of agencies such as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (the Joint Commission), College of American Pathologists (CAP), American Association of Blood Banks (AABB), among others.

THE TOTAL TESTING PROCESS

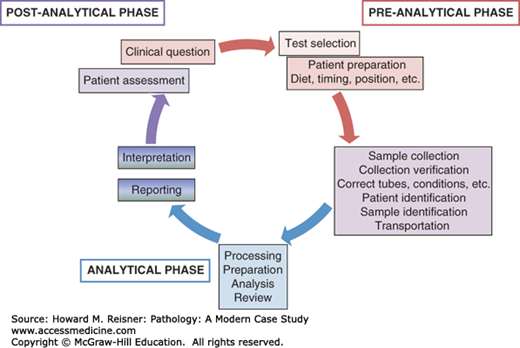

Laboratory medicine uses a systems-based approach known as the total testing process. In this, testing begins with the clinical decision to order a test and ends when the result is acted on. By approaching testing from this perspective, pathologists and laboratory scientists are able to monitor and assess all of the activities and processes that impact a test result and therefore the care of the patient. The following sections will provide a broad overview of the total testing process (Figure 6-2) with brief descriptions of key operations and concepts to prepare you to understand and use the laboratory more effectively.

FIGURE 6-2

Total testing process. Testing begins with the evaluation of the patient and the decision to order a test, and is completed when the result is acted on. In this scheme, testing is divided into the preanalytical, analytical, and postanalytical phases with many steps taking place outside the laboratory. As the colors indicate, these steps are interrelated.

QUICK REVIEW

The testing process is divided into the preanalytical, analytical, and postanalytical phases with each phase consisting of multiple steps many of which take place outside of the laboratory (Figure 6-2).

The testing process begins with an interaction between the clinician and the patient, perhaps in the form of a physical examination or a history of current symptoms. Studies of laboratory-related medical errors in diagnosis find that about half are due to failure to use the correct test indicated for the disorder in question. Admittedly, this part of the process is complicated by the fact that testing has changed rapidly over recent years both in terms of new analytes and technologies. Laboratory medicine professionals are challenged to stay abreast of these changes and it is more so for those outside.

There are several approaches used in deciding what tests to order. Some take the “shot-gun” approach, in which as many tests as possible are ordered, to cover all aspects of the differential. Such an approach is not time or cost-effective for anyone—physician, patient, or laboratory. Testing schemes will differ depending on the use, that is, the question(s) you are asking and the setting. For example, one test may be appropriate when screening an apparently healthy newborn for thyroid disease but additional tests will be needed when evaluating a 42-year-old woman who has clinical symptoms of thyroid disease.

To help put this in perspective, consider the patient presented in Case 6-1: The differential diagnosis of weight loss includes malignancy, chronic illness, gastrointestinal disease, malabsorption, drug use, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and pheochromocytoma. The shotgun approach could include several tumor markers, C-reactive protein, complete blood count (CBC) including differential, electrolytes, albumin, total protein, glucose, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine, urine drug screens, and urinary metanephrines and catecholamines. In the history, you determine that the patient has had several occurrences of vaginal yeast infections the past year, and has experienced an increase in thirst and urination. Her vital signs include a blood pressure of 119/78 mmHg and pulse of 80 bpm. She admits to being stressed during the examination because she is worried. Armed with this information, some of the disorders associated with weight loss move up in terms of likelihood and one might consider if the patient has diabetes or hyperthyroidism. One might still decide to include some basic tests to assess general health such as total protein, renal function, and a CBC, but emphasis will be placed on the glucose and TSH results.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree