KEY TERMS

Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA)

Air pollution caused by coal burning was a problem in London as early as the 17th century. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, the air of many cities was blackened with smoke from industrial and household furnaces and railroad locomotives. In 1952, an unusual weather pattern caused a particularly severe air pollution crisis in London. A layer of cold, moist air hung motionless over the city for five days, and smoke, fumes, and motor vehicle exhaust accumulated. More than 4000 deaths from both respiratory and heart disease were attributed to the foul air. Britain’s first clean air act was passed soon afterward.1(Ch.13)

Earlier, in 1948, the United States had been shocked by a similar deadly air pollution crisis caused by a similar weather pattern. A 5-day atmospheric inversion trapped the smoke and fumes of a heavily industrialized Pennsylvania valley. In the small town of Donora, population 14,000, residents suffered eye, nose, and throat irritation and breathing difficulties resulting in 20 deaths.1 The event gained national attention and helped raise awareness about the health consequences of air pollution. In 2008, on the 60th anniversary of the event, the town opened the Donora Smog Museum with the slogan “Clean Air Starts Here.”2

For most cities, the effects of air pollution were not so dramatic, but air quality was noticeably deteriorating in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. Increasingly, this was due to automobiles. Los Angeles became known for its photochemical smog, the yellowish-brown haze caused by intense sunlight acting on the complex mix of chemicals emitted in motor vehicle exhaust. The irritating effects of air pollution were obvious to everyone and were especially harmful to the health of children and people with heart and lung diseases.

Efforts by cities and states to regulate pollutant emissions proved unsuccessful, and the federal government began attacking the problem in the mid-1960s. The first emission standards for automobiles were passed in 1965, to take effect with 1968 model-year cars. The Clean Air Act of 1970 established strict air quality standards, set limits on several major pollutants, and mandated reduction of automobile and factory emissions. Since then, improving air quality has been an almost constant political battle. Environmental and public health groups have pressed for compliance and ever stricter standards, while industries, supported by political conservatives, argue that the cost of pollution control is too high, hurting the nation’s economy. Amendments to the Clean Air Act, strengthening some air quality regulations, were passed in 1977 and 1990. In general, the United States has cleaner air now than it did in 1970, but the battle is far from over.1(Ch.13)

Criteria Air Pollutants

The Clean Air Act and its amendments require monitoring and regulation of six common air pollutants, called criteria air pollutants, known to be harmful to health and the environment: particulates, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, ozone, and lead.1(Ch.13) All of these substances enter the air as a result of combustion—for energy in power plants or motor vehicles, or for solid waste disposal or industrial processes.

Particulate matter is the most visible form of air pollution—the smoke, soot, and ash that were so typical of the Industrial Revolution. Aesthetically, particulate matter is objectionable because it reduces visibility, forms layers of grime on buildings and streets, and corrodes metals. Epidemiologic studies have shown that particulates in the air also have harmful health effects. A groundbreaking cohort study conducted by Harvard epidemiologists compared the health of adults and children over the period 1975 to 1988 in six cities with markedly different amounts of particulate pollution in their air.3 Residents of Steubenville, Ohio, the most polluted city in the study, were more likely to suffer from respiratory symptoms and had poorer lung function than residents of Portage, Wisconsin, the least polluted city. Death rates in Steubenville were 26 percent higher than those in Portage. In a larger study of 151 cities, death rates were increased by 15 percent in the cities with the dirtiest air.

Early air pollution regulation focused on limiting total particulate matter. However, a number of studies, including the study of six cities, suggest that the smallest particles are the most dangerous because they can evade the body’s natural defenses and penetrate deeply into the lungs, becoming a chronic source of irritation. In 1987, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) revised the standard so that the smaller particles—those with a diameter less than 10 micrometers (PM10)—were limited. In 1997, and again in 2006, the EPA focused on even smaller particles, issuing increasingly stringent limits for particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5). In 2012, the agency proposed a further strengthening of PM2.5. States will have until 2020 to meet the new standards.4

Opponents of stricter regulations tried hard to discredit the six-city study and other data, but the evidence has continued to strengthen, showing increased hospitalizations and deaths associated with higher levels of the smallest particles. Opponents of the 1997 PM2.5 standard sued the EPA, demanding a cost–benefit analysis for implementing the new rules.5 In 2001, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a cost–benefit analysis was not necessary and that the EPA must consider only public health and safety in setting the standards.6 The importance of PM2.5 was affirmed in several other studies, including the Women’s Health Initiative, which in 2007 found that every increase of 10 micrograms per cubic meter in PM2.5 almost doubled the risk of death from cardiovascular disease.7

Sulfur dioxide is produced by combustion of sulfur-containing fuels, especially coal. It irritates the respiratory tract, but its most significant impact is as a precursor to acid rain, a major threat to the environment. Sulfur dioxide reacts with water vapor to form sulfuric acid; it also tends to stick to fine particulates in the air, both mechanisms that increase this pollutant’s potential for causing respiratory damage.1 Sulfur dioxide levels, which are highest in the vicinity of large industrial facilities, declined by 81 percent between 1980 and 2013.8

Carbon monoxide is a highly toxic gas, most of which is produced in motor vehicle exhaust. It interferes with the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and is therefore especially harmful to patients with cardiovascular disease, who are more likely to suffer heart attacks when exposed to higher concentrations of the pollutant. Carbon monoxide also affects the brain, causing headaches and impairing mental processes. Average carbon monoxide levels, which generally are highest in areas of high traffic congestion, decreased by 84 percent between 1980 and 2013.9

Nitrogen oxides are the chemicals responsible for the yellowish-brown appearance of smog. Like sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides are respiratory irritants that contribute to acid rain. They also contribute to the formation of ozone. The main sources of nitrogen oxides are on-road motor vehicle exhaust, off-road equipment, and power plant emissions.9 Nitrogen oxides levels declined by 60 percent between 1980 and 2013.10

Ozone, a highly reactive variant of oxygen, is produced by photochemical reactions in which sunlight acts on other air pollutants including nitrogen oxides. It is very irritating to the eyes and to the respiratory system, and chronic exposure can cause permanent damage to the lungs. A study of 95 large urban communities in the United States, published in 2004, found that even short-term increases in ozone levels lead to increases in mortality from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.11

Ozone levels in the air are an indicator of various other chemicals produced by motor vehicles, and they are often used as a general measure of air pollution. As discussed later, ozone is an important protective component of the upper atmosphere, but at low altitudes its effects are harmful. Although ozone levels tend to be high in many urban areas, many rural and wilderness areas may also be affected, because the wind carries the pollutants hundreds of miles from their original source. Maximum ozone levels in the United States decreased 33 percent between 1980 and 2013.12 However, in 2008, the National Parks Conservation Association and the Environmental Defense Fund filed suit to force the EPA to clean up emissions responsible for the haze that obscures the views in many national parks.13 In 2015 the EPA strengthened the standards for ozone.14

Lead is a highly toxic metal that can damage the nervous system, blood, and kidneys, posing a special risk to the development of children’s intellectual abilities. The main source of lead as an air pollutant was the use of leaded gasoline, which was phased out in the United States by 1995.1(Ch.13) While environmental lead from other sources is still a threat to children, the amount of lead in the air has decreased dramatically, having dropped by 92 percent between 1980 and 2013.15

When an area does not meet the air quality standard for one of the criteria pollutants, the EPA may designate it a nonattainment area and may impose measures designed to force the area to attain the standard. According to the EPA, 115 areas in 42 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia were classified as nonattainment areas for one or more criteria pollutant as of January 2015.16 Poor air quality that is due to ozone levels is especially widespread, affecting broad areas in California, Texas, the East Coast from Boston to Atlanta, and parts of the Midwest. In 2010, approximately 124 million people lived in counties with poor air quality.17

In addition to the criteria air pollutants, which are widespread, a large number of other toxic and carcinogenic chemicals are released into the air by local factories, waste disposal sites, and other sources. The Clean Air Act of 1970 directed the EPA to identify and set emissions standards for such hazards, but as of 1993, only eight had been acted upon: asbestos, mercury, beryllium, benzene, vinyl chloride, arsenic, radionuclides, and coke-oven emissions.1(Ch.13) Legal battles over each standard have made progress painfully slow.

Clean Air Act amendments passed in 1990 contained a number of provisions designed to speed up the process. Congress identified 187 specific chemicals for the EPA to regulate. Rather than addressing each chemical individually, however, the agency was to identify major sources that emit these pollutants and to develop technical standards that will reduce the emissions. Since then, the EPA has issued rules covering over 80 categories of major industrial sources, including chemical plants, oil refineries, aerospace manufacturers, and steel mills, as well as categories of smaller sources such as dry cleaners.18 It has also identified 33 toxic air pollutants that pose the greatest threats to public health in the largest number of urban areas and developed health risk assessments on them, producing maps of county-level risk for cancer, respiratory effects, and neurological effects.18

Strategies for Meeting Standards

Motor vehicles are the primary source of air pollution in urban areas, and the number of motor vehicles is increasing far more rapidly than the population. The standard approach for limiting air pollution from motor vehicles has been limitation of tailpipe emissions by mandating changes both in automobile engineering and in fuel. Significant improvement was achieved by the use of catalytic converters, devices that have been repeatedly improved to meet increasingly strict standards. The newest cars have reduced emissions of carbon monoxide and ozone-producing chemicals by about 90 percent and nitrogen oxides by 70 percent below those of cars without emission controls.1(Ch.13) The ban on leaded gasoline has almost eliminated lead as an air pollutant.

Because of the continuing increase in the number of cars, however, and because older cars and poorly maintained vehicles continued to emit high levels of pollutants, a number of other requirements were included in the 1990 Clean Air amendments. Special attention was paid to geographic areas that fail to meet standards for one or more criteria pollutants. These requirements include use of less polluting alternative fuels such as ethanol and reformulated gasoline, installation of vapor recovery systems on gasoline pumps, and inspection and maintenance programs that require annual measurement of tailpipe emissions on each car, with mandatory remediation on cars that fail the test. Another mandate was that automakers should develop and market “zero-emission” vehicles—electric cars—a goal that is beginning to be achieved, beginning with the increasingly popular hybrid vehicles. Complicating efforts to reduce tailpipe emissions has been the increase in the number of pickup trucks and SUVs, for which the standards for passenger cars did not apply. The rules were changed in the 1990s to require all new vehicles to meet the same standards by 2009, but vehicles manufactured under the old rules will still be on the road for years.1(Ch.13)

Ideally, the number of cars on the road in highly populated areas should be reduced. Public transportation undoubtedly benefits air quality in New York City and Washington, DC, but too many American cities—including Los Angeles—are not designed for efficient public systems. While Americans support most measures to ensure cleaner air, they consistently resist efforts to move them out of their private automobiles. Many urban areas have developed, with modest success, policies to encourage carpooling by providing high-occupancy vehicle lanes and by taxing parking spaces. Substantially higher taxes on gasoline, such as those in most European and Asian countries, would undoubtedly discourage unnecessary driving; but raising gas taxes seems to be considered political suicide by most politicians. Efficient public transport systems require some assistance from public funds—the dreaded increase in taxes. Spikes in gasoline prices in the early 21st century had some beneficial effects in encouraging people to buy smaller, more fuel-efficient, and less polluting vehicles. However when gasoline prices fell, the popularity of SUVs and vans surged again.

A variety of strategies have been effective in reducing industrial sources of pollution. Foremost among them have been installation of scrubbers on smokestacks and a move to less polluting fuels, especially away from high-sulfur coal. A new approach included in the 1990 Clean Air Act amendments is the creation of pollution allowances that can be bought and sold. Instead of requiring each factory or power plant to meet defined standards, an overall national or regional emissions goal is set, and that goal is set lower each year. Each potential polluter is assigned a fraction of that amount as an allowance, which can be used or sold. Plants that choose to clean up their technology can recoup some of their investment by selling their allowances to plants that find cleanup too expensive. This market approach was expected to achieve Clean Air Act goals with a maximum of flexibility and a minimum of political pain.1(Ch.13)

A provision of the 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments that has generated a great deal of controversy is called “New Source Review.” When the original Act was passed in 1970, it set standards for newly built power plants but did not require changes to existing plants. Because this provision led the companies to improve existing facilities without cleaning up their emissions, the 1977 rules required that companies that substantially upgraded their old plants had to bring them into compliance with the standards. Many companies, however, ignored the rules. In the mid-1990s, after years of negotiations with the industry, the Clinton administration sued seven electric utility companies in the Midwest and the South to force them to comply with the law and launched investigations of dozens of others.

When the younger President Bush took office in 2001, his administration responded to the complaints of the utilities by setting out to weaken the environmental laws. In 2002, the president proposed the “Clear Skies Initiative,” which replaced the New Source Review requirement with a market-based trading system that clearly set weaker emissions standards than those required by the Clean Air Act. Congress did not act on the proposal, so the Bush administration began to administratively change the rules. It also dropped the investigations of noncompliant companies. In late 2003, attorneys general of 15 states, in cooperation with national environmental organizations, filed their own lawsuits against a number of the polluting power plants. Most of the states that sued were in the Northeast, where air is polluted by emissions blown in from the Midwest. The legal battles continued throughout Bush’s term in office; by the end of his term, the New Source Review rule was still in place, but power plant emissions were still major sources of pollution.19,20

The Bush administration also issued rules on mercury pollution by coal-burning power plants that were later found by the courts to be inadequate and ineffective. The Bush rules used the cap-and-trade system that has been effective for air pollutants that disperse in the atmosphere; but mercury is heavy and tends to settle near the source of emission, causing local deposits that pollute soil and surface waters. Power plants, which produce more than 40 percent of mercury emissions, had lobbied heavily against strict rules requiring state-of-the-art technology at each site. The Obama administration promised to tighten the rules for mercury in accordance with the court order.21 Accordingly, the EPA in 2011 proposed stricter rules for emissions of mercury and other pollutants from coal-burning power plants.22

There was one exception to Bush’s attempts to weaken air quality rules, however: In May 2004, the administration announced rules that require vehicles using diesel fuel to meet stricter standards on emissions. Engine makers are required to install emission control systems, and refineries are required to produce cleaner-burning diesel fuel. The new regulations, which were scheduled to take effect by 2012, apply to nonroad vehicles such as tractors, bulldozers, locomotives, and barges, as well as to buses and trucks. The change was expected to significantly cut emissions of particulate matter and also, because diesel fuel contains high concentrations of sulfur, to reduce levels of sulfur dioxide in the air, helping to reduce acid rain.1(Ch.13) The program has been something of a disappointment, however, because there are many more older, polluting, diesel engines in use than new clean ones. In 2005, Congress authorized funding to retrofit old engines with a filter that reduces soot emissions. Due to budget-cutting fervor, however, the funding has not been sufficient to significantly reduce the health risks from diesel exhaust.23

A modest law that took effect in 1988, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), has had unexpectedly beneficial effects in prodding companies to voluntarily restrict their discharge of air pollutants. The law was passed in response to the infamous Bhopal disaster of 1984, in which a leak of isocyanate gas occurred at a Union Carbide pesticide factory in India, killing over 10,000 people who lived nearby. EPCRA requires businesses to report the locations and quantities of chemicals stored at their sites. This allows communities to prepare for emergencies such as leaks and chemical spills. The law also requires that manufacturers disclose information on the kinds and amounts of toxic pollutants they discharge into the local environment each year.24 Frequently, local communities, alarmed by the information, pressure the industry to cut back on their emissions. The program, known as the Toxics Release Inventory, is credited with reducing industrial releases of toxic chemicals in the United States by 54.5 percent between 1988 and 2001 and another 33 percent between 2001 and 2013.25,26

Even before September 11, 2001, some industries were pressuring the EPA to relax requirements of EPCRA, claiming, among other reasons, that publication of such information would increase communities’ vulnerability to terrorism. After September 11, the EPA has gone much further in trying to restrict public access to environmental information. Some critics claim that the terrorism argument is being used as a smokescreen to protect industry from lawsuits or bad publicity. As one of these critics is quoted as saying, “What’s tricky is finding the right balance between protection from terrorists on one hand and providing information for the neighbors so they can be safe.”27(p.107)

Urban areas that are having the most difficulty meeting air quality standards by requiring controls on motor vehicles and factories must consider regulating sources of pollution that have thus far been left alone. For example, Los Angeles banned the use of charcoal lighter fluid for barbecues and regulates the exhaust of gas-powered lawnmowers. Dry cleaners, auto body shops, and furniture refinishers are also significant sources of toxic air pollutants that are regulated in the Los Angeles area.28 In 2004, the region announced a program through which residents could turn in old gasoline lawnmowers in exchange for new, nonpolluting electric mowers.29 California still struggles with pollution associated with its ports, caused by cargo ships and the trucks that crowd the dock areas to move imported goods inland. The area’s air pollution control agency in 2012 awarded $4.8 million to replace 163 older diesel trucks with newer, cleaner models.30 In 2015, the agency announced the “Replace Your Ride” program, which provides up to $9500 to low-income residents for the replacement of their old vehicles with newer, less polluting ones.31

On a national scale, the Obama administration’s 2009 program, nicknamed “Cash for Clunkers,” which provided rebates to people who turned in old vehicles for new, more fuel-efficient ones, proved popular and helped to reduce pollution in areas with high emissions from motor vehicles.32

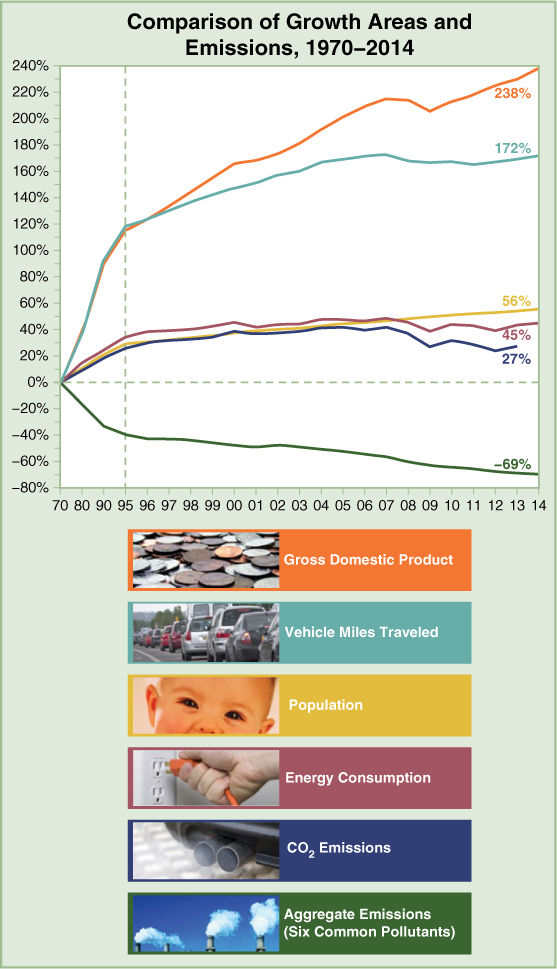

Overall, the United States has made substantial progress in fighting air pollution. As shown in (FIGURE 21-1), emissions of most common pollutants have decreased significantly since 1970 despite significant increases in the nation’s population and economic growth. In Los Angeles, concentrations of ozone, historically the most difficult pollutant to control, are now less than one-half of what they were in the mid-1970s; still, ozone levels in Los Angeles air violated federal standards on 90 days in 2013.33