DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- COPD is an insidious disease, with dyspnea being the predominant presenting symptom. However, dyspnea typically does not develop until the FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second) is ≤60% of predicted.

- The etiology of the dyspnea is multifactorial and includes the following:

- Expiratory airflow obstruction with air trapping3

- Hyperinflation that reduces diaphragm efficiency and results in abnormalities of chest wall and respiratory muscle function

- Mucus hypersecretion

- Bronchoconstriction

- Maldistribution of ventilation, resulting in ventilation-perfusion mismatching

- Physical deconditioning

- Nutritional abnormalities and weight loss

- Expiratory airflow obstruction with air trapping3

History

- Important symptoms of COPD include the following: dyspnea, chronic cough, sputum production, chest tightness, and wheezing (occasionally).

- Exacerbations of combinations of these symptoms, requiring antibiotic therapy or even hospitalization.

- Symptoms of weight loss, recurrent hemoptysis, or hoarseness should precipitate a thorough search for concurrent malignancy.

Physical Examination

- Signs on physical examination are often present only with more advanced disease and include the following: wheezing, prolonged expiration, barrel-shaped chest (hyperinflation), pursed lip breathing, accessory muscle use, and peripheral edema from cor pulmonale.

- Clubbing is not a physical exam finding that occurs in COPD and should prompt a search for additional or alternative etiologies.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

- α1-Antitrypsin levels should be checked in patients with the following problems4:

- Premature onset of COPD or significant impairment before the age of 50

- Predominance of basilar emphysema

- A family history of α1-antitrypsin deficiency or early-onset emphysema

- Chronic bronchitis with airflow obstruction in a patient who never smoked

- Unexplained bronchiectasis or cirrhosis

- Premature onset of COPD or significant impairment before the age of 50

- Genetic phenotyping should be performed if the α1-antitrypsin level is low.

Imaging

- Imaging studies, such as chest radiographs (CXR), are not sufficient to exclude lung cancer and offer little additional prognostic or therapeutic information.

- Routine chest computed tomography (CT) scanning is not indicated in the care of patients with COPD. However, annual low-dose CT protocols do detect early cancer, despite a high false-positive rate, and confer a survival advantage that is similar to routine mammography.5 These protocols are now indicated in smokers over 50 years old with a >30-pack-year history and within 15 years of the last cigarette. It is not known if coexistent COPD results in a greater survival advantage with screening, but given the increased lung cancer risk in individuals with COPD, routine screening in patients outside the guideline population will require future study.

Diagnostic Procedures

- The crucial step in the diagnosis and ongoing assessment of obstructive lung disease is formal pulmonary function testing (PFT).

- Spirometry is the only reliable means for diagnosing COPD and, importantly, also classifies the severity of the disease.6

- The sine qua non for making the diagnosis of obstructive lung disease is a reduced ratio of the FEV1 to the forced vital capacity (FVC).

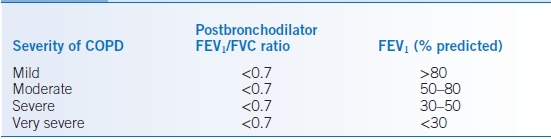

- The grading of COPD severity by PFTs is presented in Table 16-2.

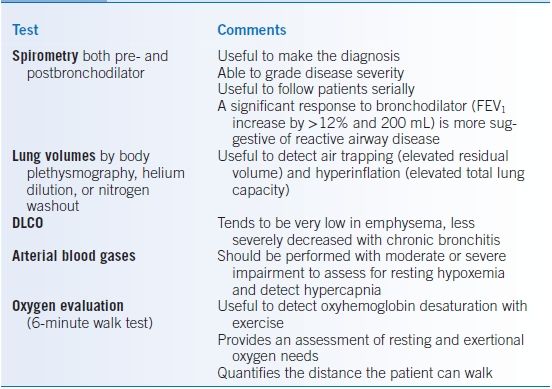

- A comprehensive pulmonary assessment often includes other testing of pulmonary function (Table 16-3). As disease severity increases, an oxygen evaluation becomes important.

TABLE 16-2 Grading the Severity of COPD

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Data from Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–555.

TABLE 16-3 Pulmonary Function Testing in COPD

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

TREATMENT

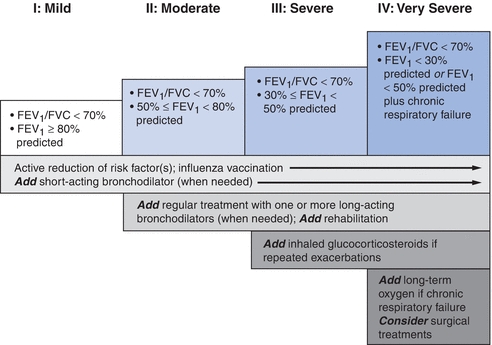

- An overview of the general management of COPD is given in Figure 16-1.6,7 Each component of this management plan will be discussed in detail below.

- General consideration should be given to comorbidities as most patients with COPD have a higher frequency of cardiac disease, osteoporosis, gastroesophageal reflux, depression, and lung cancer.

- Death from cardiac disease or lung cancer is more common than directly from COPD.

- Individuals with COPD benefit from cardiac treatments, such as β-blockers, even with severe disease.

Figure 16-1 Therapy at each stage of COPD, the GOLD guidelines. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity. (Modified from Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–555, with permission.)

Medications

Short-Acting Bronchodilators

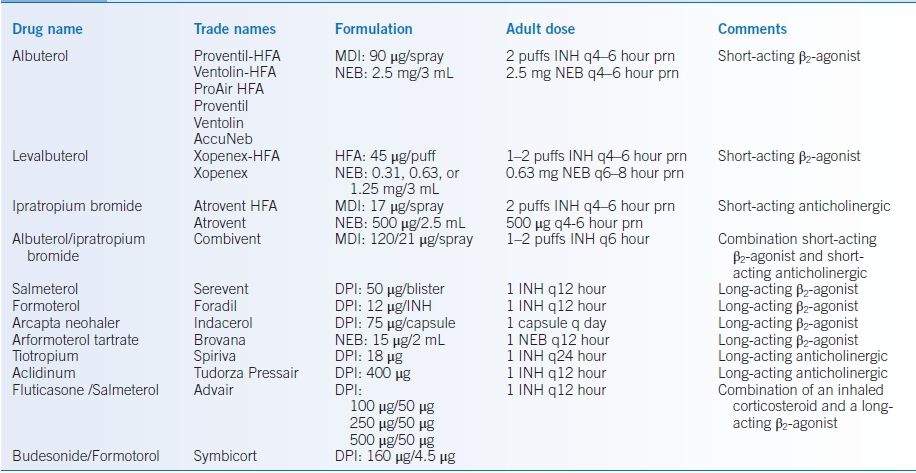

- Metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) that contain a β2-agonist, an anticholinergic agent, or both can result in improvement of airflow obstruction and hyperinflation and therefore less dyspnea. Commonly used inhalers for COPD are detailed in Table 16-4.

- These agents are the mainstay of symptomatic therapy in COPD, and patients can use two to four puffs every 4 to 6 hours.8 Regular use of short-acting bronchodilators does not preserve lung function or alter mortality.9

- Combination therapy with both anticholinergic agents and β2-agonists is appropriate in patients with more severe disease.10

- Proper MDI technique should be verified at outpatient visits, and if patients have difficulty, a spacer device may prove beneficial. Nebulized agents may also be used in patients unable to acquire proper technique.

- Frequent MDI use can lead to failure of patients to recognize an MDI containing no active medication, as propellant quantity exceeds active drug. Patients need to be counseled; presence of propellant does not ensure active drug is also present.

TABLE 16-4 Commonly Used Inhalers in COPD and Cystic Fibrosis

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DPI, dry powder inhaler; HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; INH, inhalation; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; NEB, nebulizer solution or nebulized.

Long-Acting Bronchodilators

- Current guidelines endorse the regular use of long-acting agents to improve symptoms and quality of life. Reduction in exacerbations of COPD has been demonstrated for several of these medications.6,11,12 Multiple formulations are available (Table 16-4).

- The long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs, Table 16-4) produce bronchodilation for 12 hours or more, potentially reducing nocturnal symptoms. Whether agents acting >12 hours offer greater efficacy, compliance, or simply convenience has not been addressed.

- Long-acting antimuscarinic (anticholinergic) agents (LAMA, Table 16-4) can improve airflow over a 24-hour period.

- A large trial compared LAMA with LABA therapy in predominantly GOLD 2 and 3 diseases and demonstrated a slight therapeutic advantage of anticholinergics. However, this trial and several large anticholinergic trials have excluded subjects with higher-risk cardiac disease.12

- Increased potential cardiac risk with anticholinergic agent use in clinical practice may outweigh the marginal benefit in subjects with advanced coronary disease.

- A large trial compared LAMA with LABA therapy in predominantly GOLD 2 and 3 diseases and demonstrated a slight therapeutic advantage of anticholinergics. However, this trial and several large anticholinergic trials have excluded subjects with higher-risk cardiac disease.12

- Many patients with significant dyspnea are managed with combinations of short-acting and long-acting bronchodilators. Use of both LABA and LAMA medications simultaneously likely has an additive symptomatic effect, but whether this also results in further exacerbation reduction is not known. Symptomatic dyspnea relief with simultaneous therapy is an option for some patients but may be cost prohibitive.

Inhaled Corticosteroids

- Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) combined with LABAs have a role in reducing exacerbation frequency of patients with more than one exacerbation per year and GOLD 3+ disease.11

- There is an increased risk of pneumonia, so caution should be taken to utilize these medications in combination with LABAs and for the outcome of exacerbation reduction and not symptomatic relief alone.

- ICS as a monotherapy do not confer the same level of benefit. Use as part of a combined inhaler (Table 16-4) is preferred to improve compliance.

- Oral thrush is a common side effect, and mouth rinse or using medication prior to brushing teeth typically prevents this complication.

Macrolides

- One randomized placebo-controlled trial that included subjects with greater than one annual exacerbation and GOLD 2+ COPD demonstrated a significant reduction in COPD exacerbations.13

- Subset analysis may suggest that current smokers and older subjects received less benefit.

- Thought should be given to the possibility of atypical mycobacterial disease before chronic therapy is initiated, as later eradication is complicated if the mycobacteria develop resistance to macrolide antibiotics.

- Higher than expected levels of hearing loss were observed in the trial and likely warrant audiometry testing in older patients selected for chronic use.

Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) Inhibitors

- Currently, one PDE4 inhibitor is available for use in COPD (Table 16-4).

- This medication has the narrow indication of reduction of exacerbation frequency in GOLD 3+ subjects with chronic bronchitis.14

- Similar to macrolides, the benefit in current smokers is less clear.

- GI distress is relatively common with this class of medications and may be a relative contraindication in patients with low BMI at the outset.

Methylxanthines

- Theophylline use has declined steadily due to its potential toxicity; however, this long-acting oral bronchodilator can be used as add-on therapy in patients who are still dyspneic despite maximal inhaled bronchodilator use.15

- Theophylline has multiple drug interactions, and drug levels need to be monitored routinely and whenever potentially interacting medications are added to a patient’s regimen. Therapeutic range is between 6 and 12 mg/L.

- Common side effects include anxiety, tremor, nausea, and vomiting.

- Toxicity is manifested as tachyarrhythmias and seizures.

Oral Corticosteroids

- ICS are used in COPD, but the use of chronic oral corticosteroids has less supportive clinical evidence.

- A brief trial of oral corticosteroids may benefit as many as 30% of patients with COPD with wheezing, frequent exacerbations, or severe impairment. An objective improvement in FEV1 should be evident to justify maintenance therapy with an oral steroid. Doses in the range of 40 mg/day for 1 to 2 weeks are generally initiated and then tapered off as soon as possible.

- Chronic use of oral steroids is discouraged because of the systemic side effects including osteoporosis, hyperglycemia, risk of peptic ulcer disease, immunosuppression, and cataracts.

Replacement Therapy

- Augmentation therapy with α1-antitrypsin is available and is indicated in patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency and obstructive lung disease who have quit smoking.16

- Hepatitis vaccination should be performed prior to starting therapy.

- The efficacy of this therapy has been supported by radiographic measurement of emphysema progression but not rate of change in FEV1.

- The therapy is very expensive and is given intravenously at weekly or monthly intervals to achieve trough levels equivalent to a heterozygote (80 mg/dL).

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapy

- Oxygen therapy has been shown to reduce mortality in hypoxemic patients with COPD and also improve physical and mental function.17,18

- Arterial blood gases (ABGs) should be obtained to document whether hypoxemia is present when breathing room air in individuals with more severe disease. Pulse oximetry can be used for oxygen titration after an arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation is obtained. It should be noted that in current smokers lower oxygen saturation can be present as carboxyhemoglobin levels can reach >10% but do not result in reduced noninvasive saturation measurements.

- The indications for oxygen therapy as derived from the Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group (NOTT) are as follows17:

- PaO2 < 55 mm Hg or SpO2 < 88% at rest

- PaO2 < 56 to 59 mm Hg or SpO2 < 89% if there is P pulmonale, cor pulmonale, or hematocrit >55%

- With exercise if accompanied by desaturation to levels listed above

- With sleep if accompanied by desaturation to levels listed above

- PaO2 < 55 mm Hg or SpO2 < 88% at rest

- Desaturation is common during sleep in patients with COPD, so formal overnight oximetry with oxygen titration may be helpful. If this is not available, patients are generally told to increase their resting oxygen setting by 1 L during sleep.

- Many patients develop worsening hypoxemia during acute exacerbations of COPD. These supplemental requirements may decrease after treatment of the exacerbation, so a follow-up oxygen evaluation should be performed 1 to 3 months later.

- Prescriptions for oxygen should specify the oxygen dose (L/minute) for rest, exercise, and sleep as well as the delivery system.

- There are three main forms of oxygen delivery for patients:

- Oxygen concentrators: These are large devices, which are normally placed in the patient’s home for home use. Patients need an additional portable mode of delivery, which is discussed below. Concentrators require power, and the portable tanks also function as a reserve if power failures occur.

- Compressed gas: A portable form of therapy that can occasionally be difficult to carry or push around because of the size and weight of the gas canisters.

- Liquid oxygen: This is the most expensive but most mobile form of therapy for patients. A large reservoir is typically present at home with refillable smaller portable tanks. Therefore, no concentrator pairing is need with liquid.

- Oxygen concentrators: These are large devices, which are normally placed in the patient’s home for home use. Patients need an additional portable mode of delivery, which is discussed below. Concentrators require power, and the portable tanks also function as a reserve if power failures occur.

- The oxygen is normally delivered to the patient via a continuous-flow, dual-prong nasal cannula.

- Patients with COPD rarely require very high concentrations of oxygen, as the predominant cause of hypoxemia is ventilation-perfusion mismatch. However, higher requirements necessitate the use of a reservoir system like an Oxymizer device.

- Demand pulse systems that deliver oxygen only during inspiration are also available and can extend tank life for individuals with higher flow requirements.

Surgical Management

- Bullectomy can be performed in patients with dyspnea in whom a bulla or bullae occupy at least 50% of a hemithorax and compress the normal lung.

- Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) can have excellent spirometric and functional outcomes in highly selected patients with severe emphysema (FEV1 <35%) and apical target areas, which consist of poorly functioning and volume-occupying lung, which can be surgically resected.19 Individuals with low diffusing capacities and therefore little residual functioning compressed lung do not achieve improvement with LVRS and, in fact, have increased mortality.

- Lung transplantation can be performed in patients who have severe obstruction (FEV1 <25%), hypercapnia, pulmonary hypertension, and marked limitation of activities of daily living (ADLs), but who are young without significant comorbidities.20

Lifestyle/Risk Modification

Smoking Cessation

- The beneficial effect of smoking cessation is well demonstrated by the Lung Health Study.9 Subjects with COPD who continued to smoke experience higher yearly declines in lung function than sustained quitters.

- The Framingham offspring cohort has given additional data on smoking cessation, as cessation after 40 years had less of an impact in normalizing annual decline.21 This cohort included lung function in young women, demonstrating early smoking may also cause harm via suppressing maximal lung function.

- It is well recognized that in addition to rate of decline, continued smoking also increases the risk of subsequent exacerbations and symptom severity, such as sputum production. Therefore, smoking cessation has the potential to preserve lung function, reduce symptoms, and decrease morbidity and mortality.

- Nicotine addiction causes a state of dependence; therefore, effective smoking cessation requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes consideration of pharmacologic treatment of addiction.22 Smoking cessation is discussed in detail in Chapter 45.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Dyspnea significantly impairs quality of life in COPD; pulmonary rehabilitation comprises a multidimensional continuum of services aimed at improving functional status both physically and psychologically. Rehabilitation programs can reduce exacerbation frequencies and significantly improve quality of life and ability to perform ADLs.23 Insurance benefits are important to evaluate as coverage can vary significantly.

- Any patient with moderate COPD should be considered for referral to a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation program, particularly those with persistent dyspnea on maximal pharmacologic therapy, frequent exacerbations and hospital admissions, and impaired functional status and quality of life.

- These programs consist of the following24:

- Nutrition and psychosocial support and counseling

- Graded exercise programs to enhance functionality

- Typically, sessions are three times a week with a goal of 30 minutes of continuous aerobic activity. Patients are exercised on tracks, treadmills, and bicycles and also perform arm ergometry and light weight lifting to promote upper body strength. Attention is also paid to increasing flexibility.

- Patients are monitored with pulse oximetry, and oxygen is titrated during the exercise program. The workload is gradually increased until patients reach 80% of their maximum heart rate or breathlessness.

- Often, coverage is for a single initiation period with continued lifelong exercise to be performed by the patient independently. Reinitiation of previous independent exercise often relies on the discharging physician after hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations.

- Typically, sessions are three times a week with a goal of 30 minutes of continuous aerobic activity. Patients are exercised on tracks, treadmills, and bicycles and also perform arm ergometry and light weight lifting to promote upper body strength. Attention is also paid to increasing flexibility.

- Nutrition and psychosocial support and counseling

- Oxygen assessments and potentially noninvasive cardiac stress testing should be performed prior to initiation of a rehabilitation program in patients at risk for significant coronary artery disease.

Patient Education

It is important that patients understand the nature, chronicity, treatment options, and prognosis of COPD. Educational materials are available from the American Lung Association (http://www.lung.org, last accessed January 20, 2015).

Health Maintenance

Yearly influenza vaccination is recommended for all patients, as well as a pneumococcal vaccine every 5 years. Yearly CT screening is indicated in the previously discussed high-risk population.

OUTCOMES/PROGNOSIS

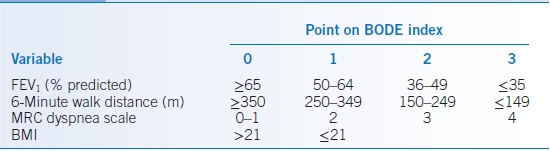

- The BODE index is a multidimensional grading system to provide a better assessment of mortality risk and includes parameters that can be obtained at routine outpatient visits25:

- Body mass index (BMI)

- FEV1 (obstruction)

- Dyspnea, graded by the Medical Research Council dyspnea scale (Table 16-5)

- Exercise tolerance (6-minute walk distance)

- Body mass index (BMI)

- The highest possible score is 10 points, with lower scores indicating a lower risk of death (Table 16-6).

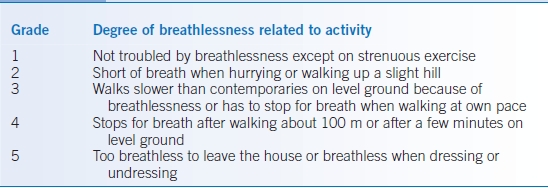

TABLE 16-5 The Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnea Scale

Adapted from Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn MB, et al. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. BMJ 1959;2:257–266.

TABLE 16-6 The BODE Index

BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; MRC, Medical Research Council.

Adapted from Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005–1012.

Acute Exacerbations of COPD

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Acute exacerbations are a common occurrence in patients with COPD and tend to occur more frequently in those patients who continue to smoke.

- These episodes are characterized by a change in the patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough and/or sputum production beyond day-to-day variability, and sufficient to warrant a change in management.

- Exacerbations are often precipitated by viral or bacterial respiratory infections but can be precipitated by other noxious stimuli like air pollution. Exacerbations account for a significant portion of the costs of managing COPD due to frequent physician visits, hospitalization, and time away from work.26

DIAGNOSIS

- Patients who are experiencing exacerbations often have worsening of their hypoxemia and hypercapnia during these episodes; evaluation is indicated to identify patients who may require hospitalization.

- Evaluation should focus on the severity of the dyspnea; the patients’ ability to sleep, eat, and care for themselves; and underlying comorbidities.

- Physical exam findings of altered mental status, hemodynamic abnormalities, increased accessory muscle use, and significant comorbidities should prompt hospitalization.

- A CXR should also be performed in these patients.

TREATMENT

- Management, whether pursued as an outpatient or as an inpatient, consists of maximizing bronchodilator therapy, corticosteroids (oral prednisone at a dose of 40 mg/day for 7 to 10 days), and antibiotics if there is evidence of purulent sputum.27

- The antibiotic chosen can be narrow spectrum to cover Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella spp., or Streptococcus pneumoniae in patients who do not have recent nosocomial risk factors. Reasonable choices include azithromycin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, an oral second-generation cephalosporin, or moxifloxacin.

- Gram-negative organisms (including Pseudomonas aeruginosa) are not unusual in patients with severe COPD, comorbid illnesses, and recurrent exacerbations, so coverage should be broadened in patients with these risk factors. For outpatients, ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin is acceptable. For inpatients, more aggressive treatment is warranted, such as piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, or levofloxacin.

Asthma

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways characterized by airway hyperresponsiveness and variable airflow obstruction in response to a wide variety of stimuli that is at least partially reversible either spontaneously or with treatment.28

- Many cell types play a role in the inflammation, in particular, mast cells, eosinophils, and Th2 lymphocytes.

- In susceptible individuals, this inflammation causes paroxysms of wheezing, chest tightness, dyspnea, and cough.

- Asthma is a chronic disease with episodic acute exacerbations that are interspersed with symptom-free periods.

- Exacerbations are characterized by a progressive increase in asthma symptoms that can last minutes to hours. They are triggered by viral infections, allergens, and occupational exposures and occur when airway reactivity is increased and lung function becomes unstable.

Classification

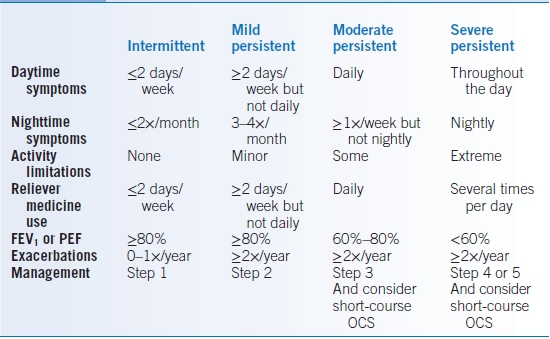

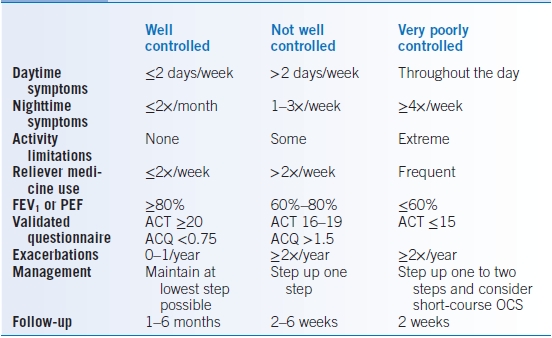

- Asthma severity should be classified based on both level of impairment (symptoms, activity limitation, lung function, and rescue medication use) and risk (exacerbations, lung function decline, medication side effects). At the initial evaluation, this assessment will determine level of severity in patients not on controller medications (Table 16-7). The level of severity is based upon the most severe category in which any feature appears. On subsequent visits or if the patient is on a controller medication, this assessment is based on the lowest step of therapy to maintain clinical control (Table 16-8).

- Patients who have had two or more exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered in the same category as those who have persistent asthma, regardless of level of impairment.

TABLE 16-7 Classification of Asthma Severity on Initial Assessment

OCS, oral corticosteroids; FEV1, forced expiratory volume over 1 second; PEF, peak expiratory flow.

GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2011—www.ginasthma.org and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program-Expert Panel Report 3, 2007—http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf

TABLE 16-8 Assessment of Asthma Control

FEV1, forced expiratory volume over 1 second; PEF, peak expiratory flow; ACT, Asthma Control Test; ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; OCS, oral corticosteroids.

Epidemiology

- In the United States, asthma is the leading cause of chronic illness among children (20% to 30%).

- The prevalence of asthma and asthma-related mortality had been increasing from 1980 to the mid-1990s, but since the 2000s, mortality has decreased.29

- African Americans are more likely than whites to be hospitalized and have a higher rate of mortality due to asthma.

Pathophysiology

Asthma is characterized by airway obstruction, hyperinflation, and airflow limitation resulting from multiple processes:

- Acute and chronic airway inflammation characterized by infiltration of the airway wall, mucosa, and lumen by activated eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages, and T lymphocytes

- Bronchial smooth muscle contraction resulting from mediators released by a variety of cell types including inflammatory, local neural, and epithelial cells

- Epithelial damage manifested by denudation and desquamation of the epithelium leading to mucous plugs that obstruct the airway

- Airway remodeling characterized by the following findings:

- Subepithelial fibrosis, specifically thickening of the lamina reticularis from collagen deposition

- Smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia

- Goblet cell and submucosal gland hypertrophy and hyperplasia resulting in mucus hypersecretion

- Airway angiogenesis

- Airway wall thickening due to edema and cellular infiltration

- Subepithelial fibrosis, specifically thickening of the lamina reticularis from collagen deposition

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- The patient’s medical history is of critical importance in establishing the diagnosis of asthma and also identifying characteristic triggers for exacerbations of the patient’s symptoms. Asthma may have its onset in infancy through adulthood, and the symptoms may be intermittent or persistent.30 Asthma is less likely to be the sole cause of respiratory symptoms in patients presenting for the first time after 50 years of age or who have >20-pack-year history of smoking.

- The history at the initial visit and all subsequent visits should focus on the following features:

- Presence of cough, which can occasionally be productive of yellow sputum and classically is worse at night or in the early morning31

- Presence of wheezing

- Shortness of breath

- A feeling of chest tightness

- Nocturnal awakenings

- A history of episodic symptoms and/or seasonal variation

- Triggers of asthma: exercise, allergen exposure (mold, pollen, dust mites, pet dander, cockroaches), changes in weather, and occupational allergens and irritants such as perfumes, cleaners, or detergents

- Symptoms suggestive of gastroesophageal reflux disease

- History of sinusitis/allergic rhinitis and postnasal drip

- History of missed work/school days

- Prior history of hospitalization and intubation

- Presence of tobacco abuse

- History of aspirin sensitivity

- Personal or family history of atopy

- Prior therapeutic response to asthma medications

- Presence of cough, which can occasionally be productive of yellow sputum and classically is worse at night or in the early morning31

Physical Examination

- Wheezing and prolonged expiratory phase can be noted, but a normal lung examination does not exclude asthma.

- Signs of atopy, such as eczema, rhinitis (pale, boggy nasal mucous membranes), or nasal polyps often coexist with asthma.

- Patients with more severe airflow obstruction may exhibit tachypnea or accessory muscle use but may not have any wheezing due to poor air movement and can ultimately develop a pulsus paradoxus.

Differential Diagnosis

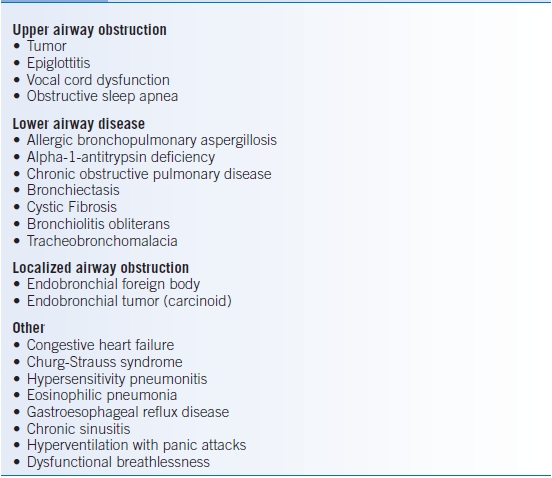

Other conditions may present with wheezing and need to be considered, especially in patients with refractory asthma. Many of the conditions in Table 16-9 can be differentiated from asthma by the absence of reversibility with bronchodilators, review of the flow volume loop, and consideration of the onset and temporal course of the symptoms.

TABLE 16-9 Common Mimics of Asthma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree