Chapter 5 Choosing the project

Making the decision

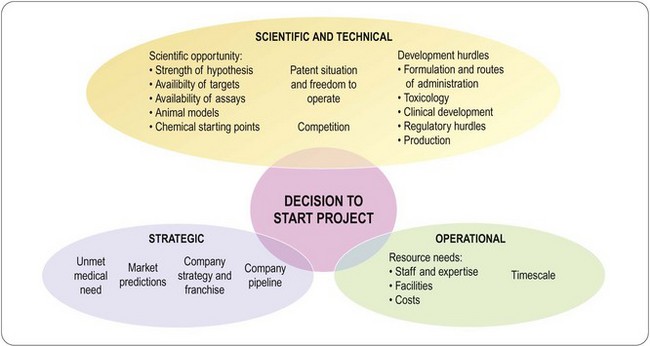

The main factors that need to be considered are summarized in Figure 5.1.

Strategic issues

Unmet medical need

• How close do we come to ‘free’? In other words, can we be more cost-effective?

• Compliance is important: a drug that is not taken cannot work. Once-daily oral dosing is convenient, but would a long-lasting injection be a better choice for some patients?

• If an oral drug exists, can it be improved, for example by changing the formulation?

• The reduction of side effects is an area where there is often a medical need. Do we have a strategy for improving the side-effect profile of existing drugs?

• Curing a condition or retarding disease progression is preferable to alleviating symptoms. Do we have a strategy for achieving this?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree