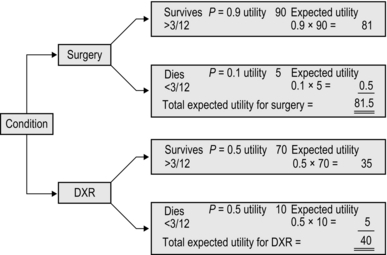

1 This three-point dictum, probably coined in the early 20th century, was never intended as a simple three-step sequence. ‘Choose well’ extends throughout, leading the celebrated American surgical teacher Frank C. Spencer, to claim that good surgery is 20–25% manual dexterity and 70–75% decision-making.1 ‘Not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted, counts.’ Notice on the Princeton University office wall of Albert Einstein ‘Choose well’, was originally directed only at the surgeon. The 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent legislation have emphasized the paramount rights of the fully informed patient2 to control what is done. Complex decisions, in particular those involving alternative or adjuvant (Latin: ad = to + juvare = to assist) therapies, intended to supplement effectiveness, are increasingly made at multidisciplinary meetings seeking a formalized consensus. 1. Make decisions on the basis of critical reading of up-to-date reports, observation, copying successful colleagues, and following your patients in order to learn as you acquire experience. Test your decisions by presenting them to respected colleagues. As you organize the information you often recognize strengths and weaknesses. 2. Statistical analysis of the gathered experience from a large number of patients has profoundly influenced practice. Prospective, double-blind, controlled clinical trials, meta–analysis of the results of different studies,3 and application of Bayesian logic (a means of quantifying uncertainty as fresh information accumulates4), may offer guidance for treatment. 3. Decision analysis offers a means of weighing all the factors and possible outcomes5 (Fig. 1.1). The subjective assessments of satisfaction values are termed utilities, an unexpected term for anticipated benefit. Decision analyses are published for a number of common conditions. Computerized decision-support systems exist, offering advice and information which can be incorporated into subsequent judgements.6 4. The patient’s valuation must prevail, and patients may measure their satisfaction with treatment using criteria that differ from those of you, the surgeon. Dignity and quality of life weigh heavily with patients alongside life expectancy. A number of terms are used in assessing this: one measure is the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).7 One year of life in perfect health is 1 QALY; a lower figure is allocated for a portion of a year in perfect health or a full year spent with a disability. 5. There are many general reviews such as evidence-based Cochrane Collaboration reports,8 and Clinical Knowledge Summaries commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence,9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention10 and Health and Safety Executive.11 6. Economic cost–benefit analysis must be added, usually as a rule by economists and health management organizations. 7. In balancing variable evidence, numerical indicators are preferred over analogue terms because numbers can be manipulated and compared. Ensure that what is chosen to be measured is valid, and not selected merely because it can be assigned a number. 8. As new methods become available, conflicting evidence emerges about effectiveness and safety compared with existing practice. Enthusiasm of originators and early promoters of treatments may lead them to confuse placebo effect with successful treatment. In case of doubt, wait for confirmation from a source unconnected with inaugurating the procedure. The eminent London physician Sir William Whithey Gull (1816–1890) humorously and cynically stated, ‘Make haste and use all the new remedies before they lose their effectiveness.’ 9. It is claimed that the tradition of doctors to customize treatments on an individual patient basis is detrimental to establishing the best method of management. Evidence-based medicine requires that fragmentation should be selectively replaced by standardization based on scientifically valid knowledge: an example cited is the success of well-vetted guidelines. Current methods of ranking outcome results for reporting to the public are imperfect, but transparency based on improved analyses should be the aim.12 10. ‘Choose well’ thus incorporates a complex challenge even before you face your patient. 1. In spite of increasing standardization and however much evidence is available, there are many factors that must be understood and negotiated with the patient (and often with multidisciplinary teams). Much of this information is subjective and may be difficult to identify, quantify or weigh. Each decision is a best guess, so it is valid only for the time it is made and must be flexible. Your initial plan is comparable to the strategy (Greek: stratos = army + agein = to lead; the overall plan) of a general before battle. Once battle is enjoined, he needs to monitor progress and alter his tactics (Greek: tassein = to arrange), responding to opportunities and threats. 2. We cannot always concentrate on a single patient when many people are ill. This is particularly true in wartime or following a civilian disaster. You must make urgent, sometimes agonizing, decisions. This process of triage (Old French = to pick, select) involves choosing to treat first those whose lives can be saved by quick action, whilst deferring treatment of those with peripheral, less lethal injuries: ‘Life comes before limb.’ 3. Particularly in acute conditions, the features may change rapidly. Take your own history and only then read the existing notes and letters. They often differ. In case of doubt, when possible defer a decision. After an interval take a fresh history and thoroughly re-examine the patient. It is remarkable how often discrepancies are then revealed. 4. Do not be too proud to take advice. The very action of arranging and presenting the problem to another person often clarifies it. 5. Choose investigations carefully from those available after asking yourself ‘What do I expect to be revealed by the result?’ Prefer investigations that confirm or exclude a diagnosis, or clarify the extent of disease. Avoid ‘trawling’ – performing a battery of tests in the hope that something emerges: as the French chemist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), stated, ‘Chance favours the prepared mind.’ If the results of investigations conflict with carefully and confidently obtained clinical findings, trust your clinical judgement. Many investigations are operator dependent: be prepared to confer with the person who has performed them. 1. Even if you are a trainee, not permitted to make and act on your decision, do not ignore the opportunity to increase your experience. Commit yourself: mentally consider the possible options as though you do have the responsibility and are defending your proposed course of action. Follow the patient to determine the outcome. Do not be an onlooker – learn from the encounter. 2. Try to consider the possibilities – the ‘what ifs… .’ and how you would modify your management in each circumstance. Take up every opportunity to present your decision and be willing to offer the evidence to justify it. It is estimated that approximately 230 million surgical procedures are performed each year worldwide.13 Operative techniques are undergoing remarkable changes as the result of technological improvements, particularly in three-dimensional imaging and minimally invasive surgery, which permits improved access to the target structures requiring surgical intervention while causing minimal damage to the interposed tissues. Many previously sacrosanct ‘rules’ of procedure no longer apply, but one tradition remains inviolate. Following the successful demonstration of general anaesthesia with inhaled ether in 1846 and the development of antiseptic, then aseptic, surgery from 1867, three visionary surgeons and friends, Theodore Kocher of Berne (1841–1917), William Halsted of Baltimore (1852–1922) and Harvey Cushing of Yale (1869–1939), pioneered the era of gentle, deliberate, aseptic, painstakingly haemostatic technique, completed with accurate apposition of viable, tension-free tissues. All subsequent technological refinements are merely instruments designed to reduce to a minimum the threat to living tissues. You cannot make the tissues heal but your disregard for them can prevent them from doing so. Your commitment to performing operations carefully and skilfully does not appear automatically as you enter the operating theatre. You bring it with you, by acquiring the habit in everyday life of striving to perform every activity carefully, faultlessly and to completion, so that it becomes second nature.14 1. Make sure that the patient is correctly identified, labelled and listed. 2. Re-assess the condition requiring surgery and check for any previous operations – and any untoward reactions. Identify and personally mark unilateral conditions. 3. Obtain a list of routine drugs being taken. 4. Identify any co-morbidity such as infection, diabetes, allergies or drug reactions. 5. In appropriate circumstances screen the cardiorespiratory, peripheral vascular, haematological, urogenital, endocrine, digestive and neurological systems. Check the nutritional state and fluid and acid-balance. 6. If the patient will require special treatment postoperatively, for example care of a stoma or a limb prosthesis, they should receive preoperative specialist instruction and reassurance. 7. Check the psychological state. 8. Make sure that the patient gives informed consent. 9. Arrange for appropriate corrections to be made to make the patient fully fit for surgery, including prophylactic antibiotics, prevention of thrombo-embolic complications, necessary modifications in the presence of prostheses and dealing with conditions normally treated with regular drugs. 10. Arrange for preparations appropriate to the procedure, such as bowel preparation. Shaving is employed much less frequently than formerly and is usually carried out immediately preoperatively or replaced by the use of depilatory preparations.

Choose well, cut well, get well

CHOOSE WELL

BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE

INDIVIDUAL PATIENTS

LEARNING

CUT WELL

PREPARE

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Choose well, cut well, get well