Cesarean Delivery

Thomas R. Moore

Background

Definition and History

The origin of the term cesarean is unclear, but the legend of Julius Caesar’s “cesarean” birth is unlikely to be true. In those ancient times, cesarean delivery was universally fatal, and Caesar’s mother was known to have lived for many years after his birth. The term may have derived from the Latin words caedere (to cut), and caesons (the term for children delivered by cesarean), or from the Roman law known as Lex Cesare, which mandated postmortem delivery so the mother and infant could be buried separately. The term “cesarean section” is redundant, derived from the Latin words caedere and secare, which both mean “to cut.”

The evolution of the current surgical technique is of interest. Maternal mortality rates for cesarean birth prior to the 20th century approached 100% owing to the almost universal uterine sepsis that followed. Consequently, very few cesareans were performed. Cesarean delivery was combined with hysterectomy in the late 19th century in an effort to reduce infection and thus prevent maternal death. Although one innovation (the “Porro” technique) involved suturing the edges of the uterine incision to the abdominal wall, allowing the lochia to drain externally significantly reduced postpartum sepsis and death; it was not until well into the 20th century that advances in surgical suture material, aseptic technique, anesthetic advances, the low-transverse incision, and antibiotics improved the safety of cesarean delivery. As a result, cesarean delivery rates in the United States increased from 4.5% of all deliveries in 1965 to 16.5% in 1980 to 24.5% in 1988 to 32% in 2007. Cesarean rates still vary widely with geographic area and type of hospital (i.e., teaching vs. nonteaching). Currently, over 1 million cesarean deliveries are performed annually in the United States alone, making it is the most common surgical procedure performed on women today.

Cesarean delivery may be indicated for fetal and/or maternal reasons, such as failure to progress in labor, fetal malpresentation, placenta previa, nonreassuring fetal monitoring (category II or III by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines), suspected macrosomia (greater than 5,000 g or 4,500 g if diabetic), active infections like herpes simplex virus or high viral load HIV, vertical uterine incisions from previous deliveries, and certain fetal anomalies such as severe fetal hydrocephalus or fetal neck masses. The majority of cesareans are still primary with repeat cesarean as an indication for 37.5% of all cesarean births in 1997. A most controversial topic today is the “cesarean-on-demand”—elective, patient-choice cesarean birth. There are data suggesting less urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse after elective cesarean, but the slightly increased morbidity and mortality associated with surgical delivery make the risk/benefit ratio for elective cesarean difficult to quantify. There is currently no standard recommendation regarding patient-choice cesarean. ACOG states, “Although the evidence does not support the routine recommendation of elective cesarean delivery, we believe that it does support a physician’s decision to accede to an informed patient’s request for such a delivery” (ACOG Committee Opinion on Ethics 2003).

Risks

Currently, cesarean delivery has an overall low maternal mortality and morbidity but is still significantly elevated over vaginal delivery. The current cesarean mortality rate in the United States ranges from 6.1 to 22 per 100,000 live births. Maternal morbidities associated with cesarean birth depend on the indication for surgical delivery, but include increased risk of endometritis (up to 20%), wound infections, increased blood loss, need for transfusion (up to 7%), thromboembolic events, anesthetic complications, and surgical complications with damage to bowel, bladder, and major pelvic blood vessels. Morbidity is highest in emergency cesarean birth, especially after prolonged labor and/or ruptured membranes.

Subsequent Outcomes

Long-term morbidities commonly attributed to cesarean delivery include uterine scar dehiscence or rupture, fetal demise and expulsion from a uterine scar, placenta previa with or without accreta, increased surgical complications from adhesions, bowel obstruction, bladder injury, and increased blood loss during future surgery. Uterine rupture occurs in subsequent pregnancy less than 1% if a low-transverse uterine incision was done, and up to 12% if a prior vertical classical uterine incision was performed. Uterine rupture may be an asymptomatic uterine “window” with minimal consequences or may be a catastrophic expulsion of the fetus into the abdomen with subsequent fetal demise. If risk factors such as a previous classical uterine incision, extensive myomectomy, or more than two previous low-transverse uterine incisions are present, repeat cesarean delivery prior to the onset of labor is usually recommended. If a vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC) is considered, an appropriate support team of anesthesiologist, nurse, and pediatrician must be available in case an immediate abdominal delivery during labor is necessary. Women undergoing VBAC must be properly informed about the potential risks/benefits of vaginal versus

repeat cesarean delivery, and this must be clearly documented in written consent.

repeat cesarean delivery, and this must be clearly documented in written consent.

Anesthesia

Choice of anesthesia is determined by the clinical situation and maternal/fetal indications for delivery. The options for anesthesia are spinal, epidural, combined spinal epidural, general anesthesia, and local anesthesia alone (least common). Regional anesthesia is most commonly used for planned cesarean deliveries or nonurgent cases. Epidural anesthesia may be used if already in place for labor analgesia and if time allows for dosing to an adequate level. Slow epidural anesthesia may be indicated in cases where general or spinal anesthesia is contraindicated. One example is a maternal cardiac disorder (i.e., pulmonary or aortic stenosis) where avoiding rapid decreases in systemic vascular resistance is important. There are significant risks of general anesthesia in the laboring parturient. Gastric emptying is slowed and significant changes in maternal physiology make airways more difficult during gestation. Antacids or histamine-2 blockers are given regardless of gastric contents in all cases prior to surgery. Local anesthesia has been used alone, but should be reserved for the rare case where no anesthesiologist is available, immediate delivery is required, and patient consent has been obtained.

Patient Preparation

The patient is generally positioned supine with leftward uterine displacement (i.e., a wedge under the right hip) to reduce aortocaval compression. Surgical site preparation with betadine or a surgical scrub or paint such as chlorhexidine (CHG) or parachlorometaxylenol (PCMX) is typically recommended. If alcohol-based paints are used it is important to allow them to dry completely because they are potentially flammable. A Foley catheter is placed in the bladder to allow decompression during surgery and urine measurement for management of intraoperative fluids. Clipping the pubic hair is usually done just prior to surgery in the operating room (OR) because shaving the previous evening may increase the risk of postoperative infection. Prophylactic antibiotics are generally recommended for all cesareans. Common practice in the United States is the use of a first-generation cephalosporin (in nonallergic patients) up to 30 minutes before skin incision to reduce the incidence of postpartum endometritis without adversely affecting neonatal outcomes. Ancef, 1 g, or 2 g if the body mass index (BMI) is >30, is a cost-effective choice. There is some evidence that providing extended coverage with azithromycin may further reduce the risk in some patient populations.

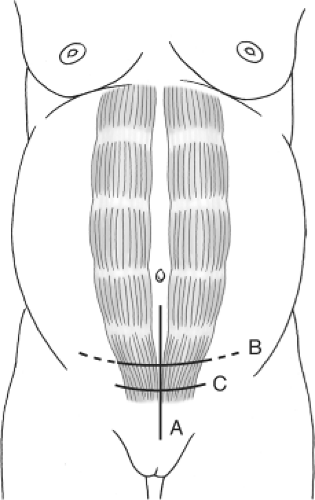

Abdominal Incision

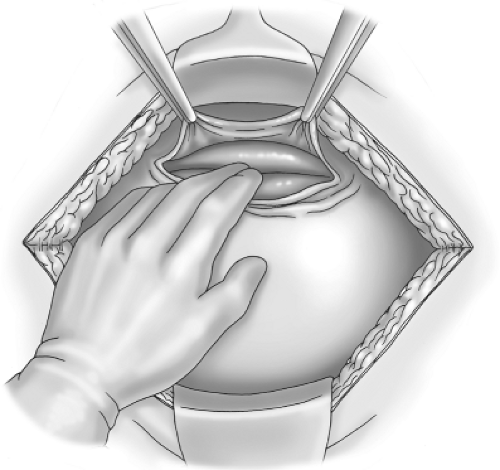

Three types of skin incisions are commonly used: Pfannenstiel, Maylard, or midline vertical (Fig. 1). In addition, there are three described modifications of the low-transverse incision—Joel–Cohen, Misgav–Ladach, and Pelosi. The choice of incision is based on the urgency of the procedure, presence or knowledge of prior scars/adhesions and presence of other pelvic pathology, and physician preference. The most common is the Pfannenstiel incision, also widely used in gynecologic surgery. The Pfannenstiel is a transverse incision made in a curvilinear fashion, typically 12 to 15 cm in length (depending on fetal size) beginning 2 cm above the pubic symphysis in the midline and extending toward the iliac crests; the superficial epigastric vessels should be avoided, ligated, or cauterized to prevent excessive bleeding in the subcutaneous space. The fascia is then incised with the knife or cautery and extended laterally as well. Kocher clamps are then used to elevate the fascia and dissect bluntly or sharply the rectus muscles from the undersurface of the fascia. All perforating bleeding vessels should be controlled as this dissection occurs. The underlying rectus muscles are then separated in the midline and the peritoneum is identified and entered by sharp or blunt dissection (never with cautery). Inspection and palpation of the peritoneum is important at this point, as previous surgery or obstructed labor may affect the bowel or bladder location underlying the peritoneum. Care should be taken to avoid these structures. The peritoneal opening is then extended and the bladder retractor is placed inferiorly. The bladder flap is created by incising the peritoneal reflection over the lower uterine segment usually with Metzenbaum scissors. The vesicouterine space is then created with blunt dissection. The bladder is retracted out of the operating field and an appropriate-sized Richardson retractor is used for exposure in the upper portion of the incision (Fig. 2).

A Maylard incision may be used if significant scarring is suspected, or in a severely obese parturient to avoid making the abdominal incision in or under the panniculus. The Maylard incision is made 3 to 4 cm above the pubic symphysis and is extended in a transverse fashion. The superficial epigastric vessels may need to be ligated and the fascia is extended laterally with scissors or cautery. The rectus muscles are then elevated and incised approximately two-thirds on each side with ligation of the deep inferior epigastric vessels located under the outer third of the rectus muscles. The rectus muscles can be incised by cautery (preferred) or sharp dissection.

A vertical skin incision is used if extreme speed is essential for delivery, if pelvic pathology such as ovarian tumor is suspected, if extensive adhesions were noted in a previous operative note, or if a vertical scar already exists. Other indications include coagulopathies or the need for perioperative anticoagulation in order to reduce the risks of subfascial or wound hematomas. Some authors suspect that vertical incisions are more prone to herniation, poor wound healing, and increased pain postoperatively, but there are multiple confounding factors associated with these observations. The midline vertical incision avoids dissection of the rectus muscles completely. A midline incision is made just above the pubic symphysis and is extended midway to the umbilicus. This is followed by dissection of the subcutaneous layers and then incision of the fascia. Once the midline separation of the rectus muscles is identified, the rectus muscles are separated, the rest of the fascia incision is extended, and the peritoneum is entered sharply. The rest of the delivery proceeds as described below.

Fig. 1. The obstetrician most commonly uses one of three abdominal incisions: midline (A), Maylard (B), and Pfannenstiel (C). Dashed lines indicate possible extension. |

There are three described modifications of the low-transverse incision. The Joel–Cohen technique begins with a

straight transverse incision slightly higher than a Pfannenstiel, 3 to 4 cm above the symphysis just below the level of the iliac spines. The subcutaneous fat is incised sharply in the middle of the incision and the fascia is also opened to a width of approximately 3 to 4 cm. The fascial incision is extended either by manual stretch or by inserting scissors into the fascial opening and pushing laterally toward the iliac spines. The rectus muscles are manually separated and the peritoneum entered digitally. The incision is stretched, a bladder flap created, and the myometrium opened in the midline and bluntly extended transversely. The uterus is closed with interrupted sutures. The Misgav–Ladach modification involves abdominal entry using a Joel–Cohen technique; however, the placenta is removed manually, the uterus exteriorized and then closed in a running, locked fashion in one layer. The fascia is closed with a running stitch and the skin with mattress sutures. Peritoneal closure is omitted. In the Pelosi modification, entry is via a Pfannenstiel incision with electrocautery used to divide the subcutaneous and fascial layers. The rectus are separated and the peritoneum entered bluntly with fingers and the incision stretched. No bladder flap is created and the uterus is entered similarly. Oxytocin is administered and the placenta is delivered spontaneously followed by uterine massage. The uterus is closed with a running locked 0-chromic and the peritoneum is not closed. The fascia is closed with a running synthetic absorbable suture and the subcutaneous layer is closed with interrupted 3-0 absorbable sutures if it is deep.

straight transverse incision slightly higher than a Pfannenstiel, 3 to 4 cm above the symphysis just below the level of the iliac spines. The subcutaneous fat is incised sharply in the middle of the incision and the fascia is also opened to a width of approximately 3 to 4 cm. The fascial incision is extended either by manual stretch or by inserting scissors into the fascial opening and pushing laterally toward the iliac spines. The rectus muscles are manually separated and the peritoneum entered digitally. The incision is stretched, a bladder flap created, and the myometrium opened in the midline and bluntly extended transversely. The uterus is closed with interrupted sutures. The Misgav–Ladach modification involves abdominal entry using a Joel–Cohen technique; however, the placenta is removed manually, the uterus exteriorized and then closed in a running, locked fashion in one layer. The fascia is closed with a running stitch and the skin with mattress sutures. Peritoneal closure is omitted. In the Pelosi modification, entry is via a Pfannenstiel incision with electrocautery used to divide the subcutaneous and fascial layers. The rectus are separated and the peritoneum entered bluntly with fingers and the incision stretched. No bladder flap is created and the uterus is entered similarly. Oxytocin is administered and the placenta is delivered spontaneously followed by uterine massage. The uterus is closed with a running locked 0-chromic and the peritoneum is not closed. The fascia is closed with a running synthetic absorbable suture and the subcutaneous layer is closed with interrupted 3-0 absorbable sutures if it is deep.

Fig. 2. The bladder flap is created with the surgeon’s index finger and forefinger as the potential space between the bladder and uterus is developed. |

These techniques have been compared in a number of instances to treat randomized trials. These trials have also been subjected to meta-analysis. In general, the Joel–Cohen–based techniques are associated with reduced blood loss and operative times. There also appears to be a reduced time for return of bowel function, less pain, and fever and shorter incision to delivery times. However, these trials do not assess the potential for serious morbidity or long-term outcomes.

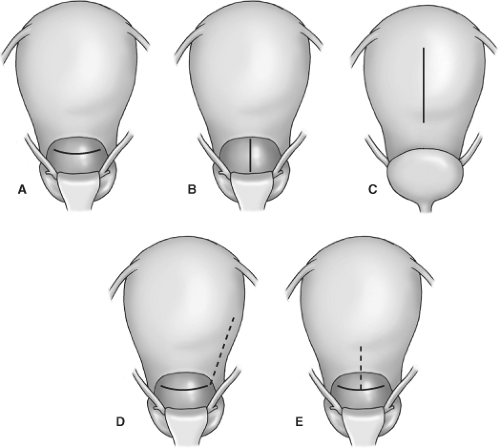

Uterine Incision

The uterine incision types are shown in Figure 3. The type of uterine incision most commonly used is a Kerr incision (low-transverse), but other choices are Krönig (low-vertical), classical, T, or J incision. Low-transverse incisions are made in the thin area of the lower uterine segment and heal

much better than an incision that extends into the contractile or upper portion of the myometrium. A low-transverse incision is made 1 to 2 cm above the bladder attachment to the uterus. A scalpel should be used to score the uterus in the midline taking care to avoid the fetus, especially if the membranes are ruptured or in emergency deliveries. To avoid fetal injury one can elevate the myometrium with an Allis clamp or enter bluntly with a Mayo clamp or finger. Extension of the incision can be made with bandage scissors or blunt dissection. If using scissors, the surgeon’s fingers should be placed underneath the uterine tissue to prevent unintentional injury to the fetus. Blunt extension is usually preferred because it is associated with less intraoperative blood loss and need for fewer transfusions postoperatively while avoiding the risk of sharp injury to the fetus. Further, blunt manual extension of the low-transverse uterine incision by cephalad–caudad (vertical) stretching has been associated with less uterine vessel injury.

much better than an incision that extends into the contractile or upper portion of the myometrium. A low-transverse incision is made 1 to 2 cm above the bladder attachment to the uterus. A scalpel should be used to score the uterus in the midline taking care to avoid the fetus, especially if the membranes are ruptured or in emergency deliveries. To avoid fetal injury one can elevate the myometrium with an Allis clamp or enter bluntly with a Mayo clamp or finger. Extension of the incision can be made with bandage scissors or blunt dissection. If using scissors, the surgeon’s fingers should be placed underneath the uterine tissue to prevent unintentional injury to the fetus. Blunt extension is usually preferred because it is associated with less intraoperative blood loss and need for fewer transfusions postoperatively while avoiding the risk of sharp injury to the fetus. Further, blunt manual extension of the low-transverse uterine incision by cephalad–caudad (vertical) stretching has been associated with less uterine vessel injury.

Indications for a classical uterine incision include, but are not limited to, anterior placenta previa, transverse back-down fetal lie, anatomic considerations such as fibroids or extensive vessels in the lower uterine segment, poorly developed lower uterine segment, or previous scarring that limits access to the lower segment. A low-vertical incision can first be made 1 to 2 cm above the bladder and then extended with bandage scissors to allow delivery. If adequate space is not achieved in the lower segment, the incision can be extended superiorly into a classical incision. The J or T incision is an extension when a transverse uterine segment does not allow delivery and must be extended either laterally (J) or in the midline (T) (Fig. 3). If any incision extends into the thicker uterine segment, patients should be counseled to avoid labor in the future due to increased risks of uterine rupture in these circumstances.

Delivery of Infant and Placenta

After the uterine incision is made, all retractors should be removed and the table lowered to allow adequate maneuvers for delivery. The surgeon’s hand should be placed below the fetal presenting part and if deeply engaged in the pelvis, the fetal part should be lifted up to the incision. If the vertex is presenting, the head may be flexed and then delivered with gentle external fundal pressure once elevated to the level of the incision. Delivery should occur as usual followed by clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord on the surgical field. Bulb or catheter suctioning of meconium is no longer recommended. A pediatrician or anesthesiologist may be present for resuscitation in cases of fetal compromise. A segment of umbilical cord may also be obtained if needed for cord gas analysis. Cord blood collection should only be done after this segment of cord is obtained. Special delivery maneuvers may be necessary for delivery of the preterm infant or multiple gestations. Care should be taken to ensure a large enough uterine incision, especially in the preterm infant. With breech presentation, head entrapment may occur if the incision is too small. This can often be relieved by extending the incision or with uterine relaxation by administering sublingual nitroglycerin. By leaving the membranes intact, en caul delivery of the intact conceptus may reduce trauma in extremely premature infants.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree