Central Splenorenal Shunts

Josef E. Fischer

Introduction

The nature of therapy for bleeding varices and cirrhosis has changed dramatically since the introduction and popularization of hepatic transplantation. However, it remains largely believed that unless the patient has demonstrated abstinence from alcohol for a period, it is inappropriate to consider hepatic transplantation. Therefore, arrest of variceal bleeding and the use of shunting procedures remain appropriate, if there is any question as to abstinence.

In considering shunting procedures, it is best that such procedures do not involve the porta hepatis so that future transplantation is not compromised. Thus, the central and distal splenorenal shunts have gained increasing acceptance by those who previously carried out portacaval shunts because they do not interfere technically with the opportunity to do an expeditious liver transplant at some future time. One should not lose sight of the fact that, in a patient with bleeding esophageal varices who shows no signs of stopping despite aggressive therapy, one should move early either to some form of emergency portacaval shunt or to transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), if varices cannot be eradicated by sclerotherapy, to stop the bleeding before the patient becomes coagulopathic and unsalvageable. Although this would make future liver transplantation difficult, it does not render it impossible.

Central and distal splenorenal shunts are generally not emergency procedures, as the decrease in portal pressure is not usually sufficient to arrest bleeding acutely. One should rely on pitressin, or its analogues, somatostatin, iced saline lavage, Sengstaken-Blakemore tubes, and sclerotherapy to provide immediate cessation of bleeding. The patient should be prepared for operation carefully at an interval, in the hospital, if possible, or at home, with abstinence from alcohol, good nutrition, vitamins, and modest exercise. If the patient is protein intolerant, a high branched-chain amino acid diet should be used to minimize encephalopathy, in addition to lactulose or neomycin, or both. The patient should be admitted to the hospital the evening before operation, and a central venous pressure or Swan-Ganz catheter placed if there is doubt about the cardiovascular status. The prevalence of left-right dissociation makes a Swan-Ganz catheter particularly useful to indicate volume status. Antibacterial washes to the abdomen and chest should have been carried out several days before to minimize the skin bacterial count and vitamin K administered to get a maximum prothrombin time. Because the Child’s class is directly related to mortality (Table 1), one should seek to obtain maximum improvement in nutrition, albumin, and overall nutritional and functional status before undertaking operation. I used a standard Nichols-type bowel preparation, in the past, with erythromycin and neomycin, in case the colon is entered inadvertently during the procedure, and it is also probably useful in preventing encephalopathy. I do use a mechanical preparation. The patient should be hydrated overnight; 10% glucose or a branched-chain-enriched amino acid parenteral nutrition solution may be used. Perioperative antibiotics are given as a single dose, usually of a first-generation cephalosporin, at the induction of anesthesia, and repeated every 3.5 hours of the operative procedure.

Table 1 Child’s Classification of Liver Cirrhosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

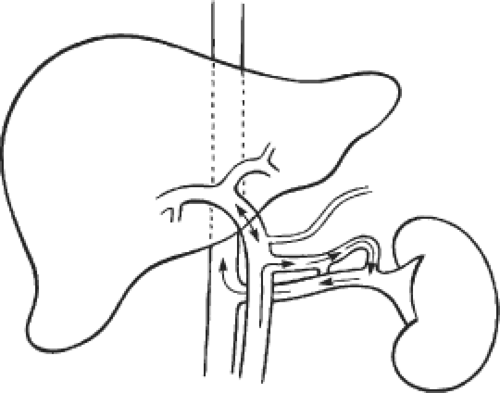

Central Splenorenal Shunt

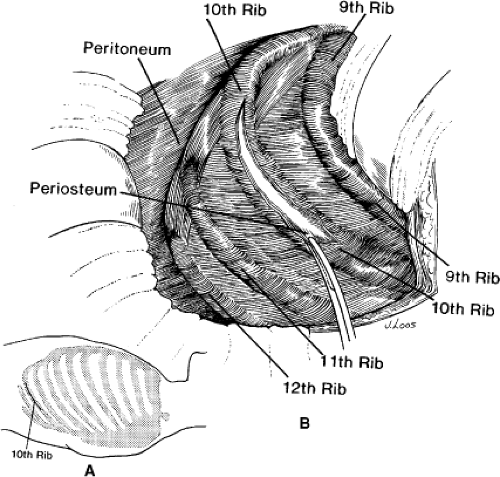

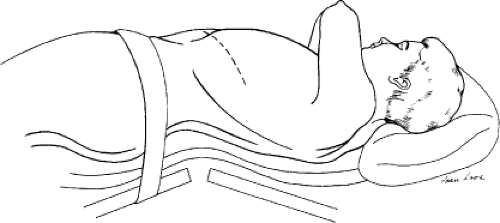

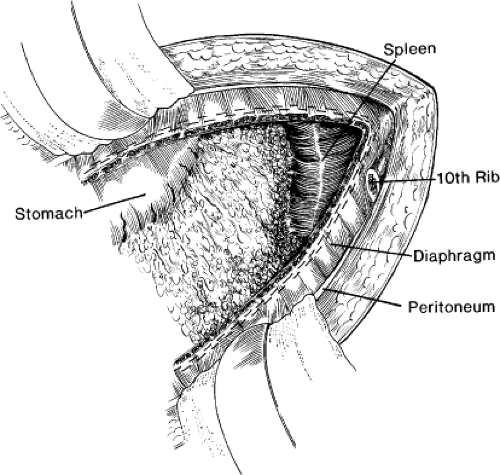

The central splenorenal shunt (Fig. 1) is carried out through a tenth rib thoracoabdominal incision, as popularized by Linton. The patient should be carefully positioned in the right lateral decubitus position, with the left side turned up at 45 degrees (Fig. 2). The entire abdomen and chest are prepared. The incision is carried out from the area of

the umbilicus through the tenth rib proximally to the posterior axillary line. The tenth rib is removed (Fig. 3). I find it easier to enter the abdomen through the peritoneum anterior to the tenth rib and then work posteriorly to resect the rib. If the break in the table is properly placed under the opposite tenth rib, the operator is positioned right over the splenic vein and where the renal vein is ultimately located centrally in the operative field (Fig. 4).

the umbilicus through the tenth rib proximally to the posterior axillary line. The tenth rib is removed (Fig. 3). I find it easier to enter the abdomen through the peritoneum anterior to the tenth rib and then work posteriorly to resect the rib. If the break in the table is properly placed under the opposite tenth rib, the operator is positioned right over the splenic vein and where the renal vein is ultimately located centrally in the operative field (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2. Positioning of the patient. The thoracoabdominal incision centered over the 10th rib (dotted line) is carried from the midaxillary line toward, but not to, the umbilicus. |

Fig. 4. View on opening the diaphragm, incising the diaphragm, and oversewing diaphragm cut edges with mattress sutures. |

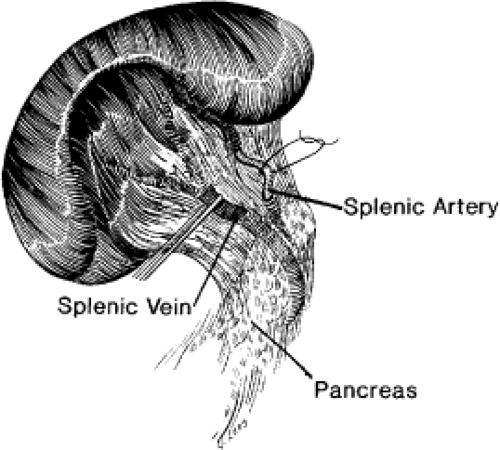

The key to the operative procedure is not to lose control of the splenic vein or the spleen with respect to hemorrhage and blood loss during the splenectomy. I have found it helpful to ligate the splenic artery before attacking the spleen. This generally can be carried out by identifying the splenic artery at a convenient point at the superior border of the pancreas, passing 2-0 silk ties around it, and ligating it (Fig. 5). This decreases the blood loss if there is an inadvertent tear in the spleen. The splenic vein may be encircled with a vessel loop.

The splenectomy is carried out by taking down the attachments to the colon between Kelly clamps and tying with cotton, if available, or silk if it is not. The retroperitoneum is then entered between Schmitt or Rienhoff clamps and suture-ligated on both sides with 2-0 silk. This is the most tedious part of the procedure, but it is essential if one is to dissect the splenic vein free in controlled fashion. One then proceeds laterally along the entire border of the spleen. It is best to take down the spleen 2 cm lateral to its peritoneal attachment (Fig. 6) because one can get a good purchase on the retroperitoneum, and suture ligation is relatively easy; it is also less bloody in that plane. Remember that the basic idea of carrying out a central splenorenal shunt is to get behind the spleen and the pancreas and bring the pancreas anterior so that the splenic vein, which is a retroperitoneal structure, can be easily identified and managed. Do not

try to take out the lateral border of the spleen bluntly; torrential hemorrhage will follow.

try to take out the lateral border of the spleen bluntly; torrential hemorrhage will follow.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree