Challenges of an Aging Society

One of the greatest challenges of the 21st century is responding to the needs of the growing number of older adults. In the United States, improvements in nutrition, health care, medicine, and sanitation have increased the average lifespan. The average American today can expect to live almost twice as long as one born in 1900. The generation of Americans born between 1946 and 1964 are referred to as Baby Boomers. As a cohort, Baby Boomers have experienced unprecedented prosperity, substantial advances in medical care and public health, higher standards of living, and significant increases in educational attainment, prompting experts to suggest that Baby Boomers will be healthiest generation ever.

Every 7 seconds, one of the 76 million Baby Boomers turns 50 years old. In 2010, there were 40.4 million people in the United States age 65 years and older. 1 While the total population increased by 9.7%, between 2000 and 2010, the older population grew by 15.1%. The number of Americans 85 to 94 years old grew fastest, increasing by nearly 20%. In the next two decades, this growth will continue. Between 2010 and 2050, the number of Americans age 65 and older is projected to double to 88.5 million. 2 The rate of disability among all those age 65 and older is relatively low (37%), but the percentage increases significantly for the oldest old, those older than 80 years. Fifty-six percent of people over age 80 reported severe disability and 64% reported their health as only fair or poor. 3 Therefore, as more and more people live long enough to experience chronic disability, there will be an unprecedented demand for health professionals with knowledge and expertise in caring for older adults and their caregivers. Health care providers must be prepared to manage a large number of older adults with chronic health care needs in the community, in hospitals, and in long-term care.

19.1.1 Longevity and Life Expectancy

Longevity refers to the average number of years an individual is likely to live. Although life expectancy is often used synonymously with longevity, it does differ. Life expectancy refers to the number of years that the average population lives. Many factors, such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle (including body weight, drinking habits, smoking, and exercise), influence an individual’s longevity. Life expectancy, on the other hand, is often used as an indictor of the overall health of a country. Life expectancy is decreased by famine, war, disease, and poor health. It is increased by improvements in health and welfare. Based on historical trends, some predict that life expectancy at birth will increase to 100 years in the United States by the year 2060; however, others point to the increasing prevalence of obesity to suggest that life expectancy of current and future generations will diminish. 4

19.1.2 Ageism

Ageism is a process of systematic stereotyping of, and discrimination against, people because they are old. 5 It includes beliefs and attitudes that justify age-based prejudice, discrimination, and subordination. Fueled by media portrayals of older adults as dependent, helpless, nonproductive, and demanding, ageism is pervasive in American culture. Ageism is also evident in the health care setting, where older adults may be avoided, their ailments are attributed simply to old age, and “elder speak” is common. 6 Elder speak is most common among young caregivers, who attempt to demonstrate caring by talking to older adults as if they were children. Examples include use of a singsong voice, phrasing statements to sound like questions, and addressing older patients by terms like “honey” and “dear.” Ageism may be hazardous to one’s health. Exposure to age stereotypes may cause older adults to direct the age stereotypes inward, resulting in a negative perception of their aging. A longitudinal study of older individuals found that those with more positive self-perceptions of aging lived 7.5 years longer than those with less positive self-perceptions of aging. 7

How can health care providers overcome ageism? Providers should respond to ageism in the same way that they respond when a person is discriminated against because of race, gender, or disabilities, and they should strive to put an end to negative stereotypes. Individual providers need to identify myths and misconceptions about aging, become aware of the special needs of older adults, and encourage older adults to actively participate in their own care. Additionally, effort should be directed toward increasing the social status of older adults by creating opportunities for older adults to contribute their wisdom and experience to society. Research also suggests that ageist stereotypes can be reduced by a comprehensive educational effort targeted at preschool children and continuing through the school years. 8

19.1.3 Achieving Multidisciplinary Competencies

Older Americans use considerably more health care services than younger Americans, and their health care needs are often complex. According to the Institute of Medicine publication Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce, 9 older adults make up only 12% of the population, yet they account for approximately 26% of all physician office visits, 47% of all hospital outpatient visits with nurse practitioners, 35% of all hospital stays, 34% of all prescriptions, 38% of all emergency medical service responses, and 90% of all nursing home use. Thus, there is an enormous need for health care professionals trained in geriatric principles.

In general, the health care workforce receives very little geriatric training and is not prepared to deliver the best possible care to older patients. 9 The Partnership for Health in Aging Workgroup on Multidisciplinary Competencies in Geriatrics developed a set of competencies that describes the essential skills and approaches that all health care providers should master by the time they complete their entry-level degree in order to provide quality care for older adults 10 ( ▶ Table 19.1). These universal competencies are relevant to all health care disciplines.

Domain 1: Health Promotion and Safety |

|

|

|

|

|

Domain 2: Evaluation and Assessment |

|

|

|

|

|

Domain 3: Care Planning Coordination (Including End-of-Life Care) |

|

|

|

|

Domain 4: Interdisciplinary and Team Care |

|

|

Domain 5: Caregiver Support |

|

|

|

|

Domain 6: Health Care Systems and Benefits |

|

|

|

19.1.4 Teamwork and Interdisciplinary Care

Interdisciplinary care is a philosophy and process of care that integrates the specialized knowledge of multiple disciplines. Because the care needs of older adults tend to be complex, the American Geriatrics Society 11, 12 advocates interdisciplinary care for older adults. Interdisciplinary care results in better patient outcomes, improved function, decreased readmission to acute care facilities, and improved medication adherence. Team members also benefit from improved morale, better job satisfaction, greater efficiency, lower staff stress, and fewer errors. 13

Despite the many benefits of interdisciplinary collaboration, adoption has been slow and dissemination is not widespread. Young and colleagues 12 note that many health professionals are traditionally educated in isolation and fail to understand various disciplinary perspectives. In addition, many lack essential skills in both teamwork and geriatrics. Therefore, to be most effective, health care providers should be skilled in working as effective team members. Team members need to understand the purpose of the team and the roles, unique competencies, and skills of other team members ( ▶ Table 19.2). They must also be willing to work in partnership, understand sources of conflict, and develop basic skills in negotiation and conflict resolution.

Clinical or Counseling Psychologists | Psychologists diagnose and treat mental disorders, learning disabilities, and cognitive, behavioral, and emotional problems, using individual, child, family, and group therapies. |

Geriatrician | A physician certified in the treatment of diseases common to older adults. |

Health Care Social Worker | Social workers provide individuals, families, and groups with the psychosocial support needed to cope with chronic, acute, or terminal illnesses. Services include advising family caregivers, providing patient education and counseling, and making referrals for other services. They may also provide care and case management or interventions designed to promote health, to prevent disease, and to address barriers to access to health care. |

Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) Licensed Vocational Nurse (LVN) | LPNs and LVNs care for ill, injured, or convalescing patients or persons with disabilities in hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, private homes, group homes, and similar institutions. They may work under the supervision of a registered nurse. |

Neurologist | A physician who specializes in the investigation, diagnosis, and treatment of neurologic disorders. |

Nurse Practitioner | A registered nurse who is prepared through advanced education and clinical training to provide a wide range of preventive and acute health care services. A nurse practitioner may diagnose and treat acute, episodic, or chronic illness independently or as part of a health care team; may focus on health promotion and disease prevention; may order, perform, or interpret diagnostic tests; and may prescribe medication. |

Nutritionist | Nutritionists plan and conduct food service or nutritional programs to assist in the promotion of health and control of disease. They may supervise activities of a department providing quantity food services, counsel individuals, or conduct nutritional research. |

Occupational Therapist | A therapist who assesses, plans, organizes, and participates in rehabilitative programs that help build or restore vocational, homemaking, and daily living skills, as well as general independence, to persons with disabilities or developmental delays. |

Pharmacist | Pharmacists dispense drugs prescribed by physicians and other health practitioners and provide information to patients about medications and their use. A pharmacist may advise other health practitioners on the selection, dosage, interactions, and side effects of medications. |

Physical Therapist | Physical therapists assess, plan, organize, and participate in rehabilitative programs that improve mobility, relieve pain, increase strength, and improve or correct disabling conditions resulting from disease or injury. |

Physician assistant (PA) | The PA provides health care services typically performed by a physician, under the supervision of a physician, including conducting complete physicals, providing treatment, and counselling patients. |

Psychiatrist | A physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. |

Registered Nurse (RN) | RNs assess patient health problems and needs, develop and implement nursing care plans, and maintain medical records. They administer nursing care to ill, injured, convalescent, or disabled patients, and they may advise patients on health maintenance and disease prevention or provide case management. |

Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) | SLPs assess and treat persons with speech, language, voice, and fluency disorders. They may select alternative communication systems and teach their use, and they may perform research related to speech and language problems. |

Data from: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Division of Occupational Employment Statistics, www.bls.gov/OES. | |

19.1.5 Preventing and Treating Frailty

While the majority of older adults live healthy and active lives, the incidence of frailty increases with age. Frailty is a progressive physiologic decline in multiple body systems and includes a loss of function, decreased physiologic reserve, and increased vulnerability to disease and death. 14 There is evidence that frailty is a distinct clinical syndrome characterized by three or more of the following criteria: unintentional weight loss (10 lbs in past year), self-reported exhaustion, weakness (as measured by grip strength), slow walking speed, and low physical activity. 15 Frailty is a risk factor for falls, worsening mobility, impaired activities of daily living, hospitalization, and death. The causes of frailty are not fully understood, but they are thought to include chronic inflammation, impaired immunity, neuroendocrine dysregulation, and metabolic alterations. 16 More recently, frailty has been recognized not only as a biological state, but also to include interrelated risk factors in the physical, psychological, and social domains. Identifying older adults who are frail or at risk for frailty is important because it can provide opportunity to intervene with exercise, nutritional maintenance, oral health, environmental modifications, and family and professional caregiver education. 17 For those who are frail, the goal is to minimize further weight loss, to maintain muscle mass and strength, and to reduce fall risk. 18

19.2 Normal Age-Related Changes

Although people age at different rates and the effects of aging on healthy individuals vary, there are normal changes in body composition that accompany aging ( ▶ Table 19.3). In general, normal age-related changes reduce reserve capacity, diminish the ability to maintain homeostasis, and impair regulation of body systems. Health care providers caring for older adults must be aware of normal age-related changes and how these changes can contribute to adverse drug reactions, atypical and altered disease presentation, and problems with communication.

System | Age-Related Change | Implications |

General | Increased body fat Decreased total body water Decreased total body protein | Increased risk for adverse drug events resulting from changes in volume of distribution |

Sleep | Circadian rhythm change Decreased sleep efficiency and slow wave sleep | Sleep is less deep Frequent awakening may be common |

Senses | Eyes

Ears

Smell

Taste

| Presbyopia Decline in near vision Presbycusis Decreased high-frequency acuity Increased risk of falls and accidents May result in decreased sense of smell May result in altered sense of taste |

Skin | Decreased elastin and collagen Decreased ability of skin to retain moisture and dissipate heat Decreased elasticity and resiliency Decreased subcutaneous layer | Tissue more fragile Loss of moisture Increased risk of pressure ulcers Increased risk of heat stroke |

Endocrine | Insulin resistance may alter conversion of glucose into energy Decreased aldosterone and cortisol | Increased risk of type 2 diabetes |

Respiratory | Decreased cough reflex Decreased lung and chest wall elasticity | Increased risk for microaspiration |

Cardiovascular | Decreased maximum heart rate Heart rate and blood pressure slower to return to normal after stress Increased peripheral resistance Diminished aortic elasticity Increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure Decreased number of pacermaker cells Less-sensitive baroreceptors | More irregular heartbeats Diminished cardiac output Less able to respond to changes in blood pressure |

Gastrointestinal | Decreased saliva Diminished large bowel motility Diminished hepatic synthesis Reduced capacity to absorb calcium Reduced sensation of thirst | Increased risk of dry mouth Altered/slowed metabolism of some medications Increased risk of constipation Increased risk of dehydration |

Renal | Decreased size of urinary bladder Decreased size of kidney Decreased renal blood flow Decreased glomerular filtration rate | Increased risk of drug toxicity Increased risk of renal damage |

Genitourinary | Decreased hormonal response and impaired ability to conserve salt Decreased bladder capacity Increased residual urine | Increased risk of dehydration Increased risk of urinary tract infections and incontinence |

Female | Decreased estrogen levels Ovulation cessation Diminished vaginal and cervical secretions Weakening of the pelvic floor | Increased risk of incontinence, cystocele, and urethrocele Increased risk of dyspareunia |

Male | Enlarged prostate gland Decreased testosterone Decreased testicular size Decreased sperm production | Increased risk of erectile dysfunction Increased risk of prostatic obstruction |

Musculoskeletal | Decreased height Increase in weight until age 60 Increased body fat mass Decreased lean muscle mass | Increased risk of reduced muscle strength resulting from inactivity, poor nutrition, and chronic illness |

Nervous system | Reduced semantic knowledge Decline in rate of information processing | Decreased word retrieval Slower rate of encoding may interfere with long-term memory |

19.2.1 Adverse Drug Reactions

More than one-third of prescription medications are taken by people over the age of 65. While pharmaceuticals can improve morbidity and delay mortality, a significant proportion of older adults experience adverse drug reactions. It is estimated that over 40% of preventable adverse events are serious, life-threatening, or fatal, and nearly 30% of hospital admission are attributable to adverse drug events. 19 Normal age-related changes make older adults more vulnerable to adverse drug reactions. For example, aging is associated with a relative decrease in total body water and lean muscle mass and an increase in percentage of body fat. Water-soluble drugs, such as aminoglycosides, have a smaller volume of distribution in older adults. Therefore, lower doses are needed to attain a therapeutic effect. Similarly, drugs that are distributed into lean muscle mass, like digoxin, also have a smaller volume of distribution. If older adults are given the same dose as younger adults, signs of digoxin toxicity, such as confusion, vision changes, and vomiting, can occur. Similarly, fat-soluble drugs like diazepam have a greater volume of distribution that results in delayed clearance, causing the drug to accumulate. Common adverse effects of diazepam are sedation, amnesia, and ataxia. In addition, because most medications are excreted through the kidneys and age is associated with a decline in kidney function, the elimination of drugs is often slowed in older adults. Furthermore, changes in the central nervous system make older adults more sensitive to psychoactive medications and those with anticholinergic effects, which may cause increased blood pressure and heart rate, drowsiness, urinary retention, mental status changes, dry mucous membranes, slurred speech, and vision changes.

A famous adage in pharmacotherapy for older adults is “start low and go slow.” Starting low addresses the changes in volume of distribution, and going slow addresses the changes in metabolism and excretion. 19 Health care providers should be aware that using multiple medications increases the risk of drug–drug interactions, noncompliance, and adverse effects. 20 In addition, providers should frequently review the patient’s medication history, know the actions and toxicity profiles of medications, and educate patients and caregivers about safe medication storage, utilization, and disposal ( ▶ Table 19.4).

Things for Health Care Providers to Consider |

Assess drug regimen at each encounter |

Prescribe as few drugs as possible |

Avoid adding new drugs to treat side effects of current medications |

Discuss potential side effects with patients and caregivers |

Consider whether a nonpharmacologic alternative exists |

Discontinue medications without known benefits |

Provide written instructions |

Work as part of an interdisciplinary team |

Things for Patients and Caregivers to Consider |

Talk with health care providers about all medications, including over the counter medications, eating habits and lifestyle |

Be sure to understand how to take medication, what the intended effect is, and the potential unintended side effects |

Keep a list of all medications, doses, and instructions |

Dispose of all outdated, expired, and leftover prescription medicines from previous illnesses or conditions |

Store medications in a cool and dry location away from bright light. |

Lock up your medications if children are around |

Keep medicine in the bottles they came in and do not mix different medicines in the same bottle |

Have a “medicine check-up” at least once a year |

19.2.2 Altered and Atypical Disease Presentation

Identifying health conditions among older adults can be challenging. Some older adults may not report symptoms because they learn to tolerate symptoms that develop slowly. Some older adults may also be reluctant to report symptoms if they fear the diagnosis or treatment. In addition, older adults may not seek treatment for conditions that they attribute to old age. Health care providers may also reinforce these misperceptions. Common conditions mistaken as a normal part of aging include memory loss, urinary incontinence, weight gain, falls, and vision or hearing loss. Health care providers should screen for these common, manageable conditions so that they may be effectively treated to prevent them from impairing function and quality of life.

Providing health care to older adults may also be complicated by atypical presentation of acute illness. Older adults with severe acute or chronic conditions may present with vague, nonspecific symptoms, such as confusion, apathy, self-neglect, and falls. 21 In addition, some conditions present differently in older adults than in younger adults. For example, major depression, which typically includes sadness as a major symptom, may present as confusion or somatic symptoms in the elderly. The typical signs of infection, such as an elevated white blood cell count, fever, and tachycardia, may be absent in older adults. In the elderly, an acute myocardial infarction may not be associated with chest pain. Instead, older adults may report vague illness, nausea, and exercise intolerance. Nonspecific symptoms are warning signs of acute illness or exacerbation of underlying chronic conditions. Therefore, health care providers should search for the cause of vague symptoms, such as fatigue, confusion, and falls.

19.2.3 Communication

It is estimated that 16 million older adults experience communication challenges. 22 With normal aging, communication skills can change subtly due to decreased vision and hearing acuity. Some aging adults have preexisting communication disorders, while others develop new communication disorders as they age, such as Parkinson’s disease, stroke, or dementia. Yorkston 22 provides the following recommendations to improve communication in the health care setting: know the patient’s communication strengths and weaknesses, use sensory aids, take extra time, make sure the environment is communication friendly (well lit, quiet, allows face-to-face interaction), avoid medical jargon, speak slowly, supplement verbal instruction with pictures and writing, confirm understanding with teach-back approaches, limit the amount of information in one session, and provide take-home material at an appropriate reading level.

Health literacy can also pose challenges to communication with older adults. Health literacy is the degree to which individuals can obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health care decisions. It includes the ability to interpret documents, to read and write, to use quantitative information, and to speak and listen effectively. 23 Although a significant proportion of the general population has low health literacy, there is a higher prevalence of poor health literacy in the older adult population. 23 Low health literacy is linked to poor health outcomes, such as higher rates of hospitalization and less frequent use of preventive services. Many resources are available to health care providers who wish to improve their communication, including Gateway to Health Communication and Social Marketing Practice from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) available at http://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/; a free online course from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) available at http://www.hrsa.gov/healthliteracy/, and a guide to writing and designing health Websites at http://www.health.gov/healthliteracyonline/about.htm. All of these sources recommend the use of “plain language,” which is communication that users can understand the first time they read or hear it. It includes the following: information organized so that important points come first, breaking complex information into understandable pieces, using simple words, and using the active voice. Additional strategies to improve the usability of health information include using pre- and post-tests, limiting the number of messages, focusing on behavior, checking for understanding, supplementing with pictures, and using a medically trained interpreter or translator.

19.3 Staying Healthy

19.3.1 Preventive Care

It is never too late or too early to implement healthy lifestyle and preventive strategies. Older adults can benefit from health-promotion strategies just as younger individuals do. Health care providers should organize health-promotion programs and strategies for older adults that account for physiologic, social, and economic changes associated with aging. Research indicates that investing in primary prevention improves the health and longevity of future cohorts of older adults at a relatively low cost. 24 For example, smoking cessation results in substantial gains in life expectancy. Lowering cholesterol with statin medications reduces the risk of cardiac events and stroke. Exercise decreases cardiovascular events and improves quality of life. Lowering blood pressure reduces strokes and all-cause mortality, and annual influenza vaccination is one of the most cost-effective methods of prolonging life. 25

Screening

Healthy People 2020 provides national objectives for improving the health of all Americans . 26 For the first time, it includes objectives aimed at improving the health, function, and quality of life of older adults . 27 Because early detection can be essential to effective treatment, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also publishes a set of clinical preventive services recommended for people 65 years old and older . 28 Included in the guidelines are core services, such as influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations and screening for lipid disorders, for colorectal cancer, for diabetes, for depression, and for osteoporosis and breast cancer in women.

Injury Prevention

Falls are a leading cause of death due to unintentional injury. Falls can also lead to fear of falling, sedentary behavior, impaired function, and lower quality of life. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes a guide for developing effective fall-prevention programs. Essential components of an effective fall-prevention program for community-dwelling older adults include education, exercise programs, medication management, vision checks and correction, and home hazard assessment. The guide is available at http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Falls/community_preventfalls.html.

19.3.2 Exercise

Regular exercise decreases mortality and age-related morbidity in older adults. It also reduces the risk of chronic diseases associated with advancing age, such as hypertension, diabetes, colon and breast cancer, and depression. 29 Older adults should engage in endurance, resistance, and flexibility exercises ( ▶ Table 19.5). Physical activity should begin at low levels for older adults who are highly deconditioned, are functionally limited, or have chronic conditions that affect their ability to perform physical tasks. The frequency, intensity, and duration of exercise should progress as tolerated. For those who are very frail, muscle strengthening and balance training may need to precede aerobic training. Those who cannot undertake the minimum amount of physical activity should be encouraged to perform physical activities as tolerated to avoid being sedentary. Balance exercises should be added for individuals who fall frequently and those with mobility problems. Older adults who wish to improve their fitness should exercise more than the recommended minimum amounts of physical activity.

Exercise | Frequency | Examples |

Endurance | Moderate intensity: accumulate at least 30–60 minutes/day to a total of 150–300 minutes/week Vigorous intensity: a total of 75–150 minutes/week | Walking Aquatic (aerobics, swimming) Cycling |

Resistance | 2 times/week | Progressive weight training Weight-bearing calisthenics Stair climbing |

Flexibility | 2 times/week | Any activity that maintains or increases flexibility, using sustained stretches for each major muscle group |

19.3.3 Nutrition

The overall nutritional requirements for protein, vitamins, and minerals remain largely unchanged with age. However, energy and overall caloric requirements decrease. Therefore, older adults are challenged to eat fewer calories while maintaining a diet with sufficient nutrient-rich food. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010 30 recommends that all adults eat a variety of fruits and vegetables, at least three ounces of whole grains, and three servings of fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products fortified with vitamin D. They also recommend that older adults consume foods fortified with vitamin B12, reduce sodium intake to 1,500 mg per day, reduce calories from saturated fatty acids to <10% of total caloric intake, and reduce cholesterol to <300 mg per day.

Hydration

The sensation of thirst is often diminished in older people. In addition, some older adults may limit their fluid intake to avoid trips to the bathroom; others are prone to dehydration from diuretics used to treat hypertension and heart disease. Dehydration can lead to low blood pressure, constipation, confusion, and headaches. Six to eight glasses of fluid are recommended each day. Older adults with limited access to fluids (e.g., those in hospital) should be offered, and encouraged to consume, fluids frequently.

Vitamins and Minerals

Most vitamin and mineral needs remain the same in older adults, with the exception of calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B12. To maintain bone health, older adults should consume adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D. Both men and women over age 65 should consume 1,200 to 1,500 mg of calcium per day and 600 to 800 IU of vitamin D per day. Calcium-rich foods include dairy products, fortified cereals and fruit juices, dark green leafy vegetables, and canned fish with soft bones. Very few foods contain vitamin D. Instead, fortified foods, such as milk and cereals, provide most of the vitamin D in the American diet. Some older adults may require calcium supplements with vitamin D to obtain the recommended allowance. Vitamin B12 is required for proper red blood cell formation and neurologic function. Over age 50, the body’s ability to absorb vitamin B12 decreases. The Dietary Guidelines 30 recommend that nutrients be obtained from food, but dietary supplements may be advantageous in some situations to increase intake of a specific vitamin or mineral.

19.4 Iatrogenesis and Hazards of Hospitalization

While hospitalization may be necessary, many hospitalized older adults experience iatrogenic complications unrelated to the diagnosis for which they seek treatment. Those who are frail and who have multiple comorbidities, cognitive impairment, functional impairments, psychosocial issues, and sensory impairment are at risk for iatrogenesis. Iatrogenesis is a state of ill health or an adverse event that is caused by, or the result of, a well-intended health care intervention. Common iatrogenic events in hospitals include adverse drug events, complications of diagnostic interventions, hospital-acquired infections, and geriatric syndromes, such as falls, delirium, functional decline, and pressure ulcers. Sadly, iatrogenic events can lead to functional decline, nursing home placement, hospital readmission, caregiver stress, and death. Cascade iatrogenesis is defined as the serial development of multiple medical complications that can be set in motion by a seemingly innocuous first event. 31 An example of cascade iatrogenesis is an adverse drug reaction causing a patient to fall, causing an immobilizing injury, resulting in a pressure ulcer and pneumonia.

Hospital-related adverse events occur in approximately one third of hospital admissions admissions. Patients who experience adverse events are older, have higher mortality, and have longer hospital stays. 32 Many patients do not regain their prehospital level of functioning. More than three-fourths of residents in assisted living facilities are discharged to nursing homes after hospitalization rather than returning home . 34 For multifaceted conditions, removing or treating one factor in isolation is usually not sufficient. All vulnerabilities and precipitating factors need to be addressed. 34 The Fulmer SPICES acronym is an effective guide to conducting an assessment for the factors that may precipitate cascade iatrogenesis. 35

S: Sleep disorders

P: Problems with eating and feeding or Pain

I: Incontinence

C: Confusion

E: Evidence of falls

S: Skin breakdown

19.4.1 Sleep Disorders

With age, the required number of hours of sleep does not change; however, older adults have an increase in stage 1 and 2 sleep (light sleep) and a decrease in stages 3 and 4 sleep (deep sleep). Sleep quality and sleep efficiency also decrease with age. Therefore, many older adults have sleep-related complaints, including waking up earlier, disturbed sleep, increased nighttime wakefulness, decreased total time asleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness. 36 In addition, sleep disorders (e.g., restless legs syndrome, sleep apnea), discomfort (e.g., pain, anxiety), and sleep-impairing medications (e.g., cold medications, steroids) are more common among older adults.

Hospitalized older adults are especially vulnerable to disrupted sleep, and sleep disturbance is common. Environmental noise, disrupted light/dark cycle, caregiver interruptions, pain, and stress all contribute to a less than restful environment. 33 Sleep medications, such as sedative-hypnotics, should be avoided in older adults because they impair sleep quality, cause residual sedation, increase risk of falls, and impair memory and function. Instead, nonpharmacologic sleep-promoting measures have demonstrated significant benefit. 38 To develop individualized sleep-promotion strategies, health care providers should begin with an assessment of the patient’s sleep history and typical sleep pattern, including typical bedtime and rise time, bedtime routines, medications, and subjective assessment of sleep. An interdisciplinary assessment may be required to identify and treat sleep disorders or other physical conditions that interfere with sleep. Interventions to promote relaxation include massage, music therapy, guided imagery, and progressive muscle relaxation. Environmental modifications include noise reduction, light adjustment, decreased nighttime interruptions, and increased meaningful daytime activity.

19.4.2 Problems with Eating

Malnutrition is a serious condition that negatively affects the health of older adults. A multinational study found the combined prevalence of malnutrition was 22.8%, ranging from approximately 6% in community-dwelling older adults to 38.7% in hospitalized patients and 50.5% in the rehabilitation setting. 39 Poor nutrition is not an inevitable part of aging; however, normal age-related changes in body composition, changes in appetite, and impaired sense of taste and smell make older adults more vulnerable to malnutrition. Furthermore, medical illness can interfere with digestion and absorption, can increase nutritional requirements, or may necessitate dietary restrictions. Many medications, such as antidepressants, antihypertensives, and antibiotics, can suppress appetite. Older adults may also face financial or structural barriers to attaining and preparing sufficient high-quality food.

Malnutrition is a state in which there is a deficiency or excess of energy, protein, and other nutrients that has measurable adverse effects in the body, on function, and on clinical outcomes. Protein-energy malnutrition is caused by an imbalance between intake and the body’s requirements. Involuntary weight loss can lead to muscle wasting, decreased immunocompetence, and increased rates of complications. Malnutrition is associated with infection, diminished strength, depression, and death. 40

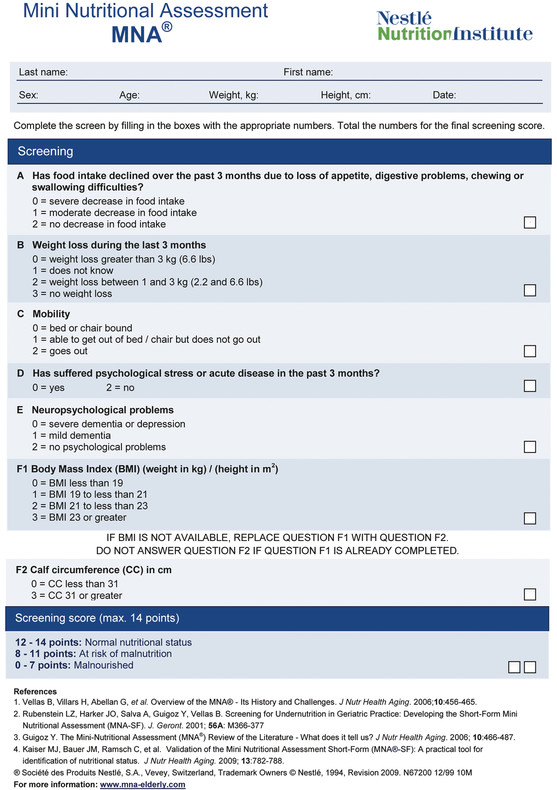

The progression of malnutrition is often insidious and undetected. Therefore, screening is recommended for all older adults at least once a year, and every 3 months for institutionalized patients and those who are underweight (body mass index <19) and those who are overweight (body mass index >25). 41, 42 Identifying older adults who are malnourished or at risk allows the clinician to intervene early to prevent further deterioration and to improve patient outcomes. 43 The Mini Nutritional Assessment-SF (MNA-SF) is a screening tool to help identify older adults who are malnourished or at risk for malnutrition ( ▶ Fig. 19.1). Literature related to the MNA is available at www.mna-elderly.com.

Fig. 19.1 The Mini Nutritional Assessment-short-form (MNA-SF).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree