7 Care of the Elderly

Blackouts

What should you ascertain from the history?

• What was patient doing at the time (e.g. micturition, change in posture, coughing).

• Symptoms preceding blackout:

• Witness history: any witness(es) to give description of the blackout.

Epilepsy in the elderly

• Focal fits or a focal origin of generalised seizures are common in the elderly (accounting for 80% of fits in this age group).

• Post-ictal confusion, headache and focal signs (Todd’s paresis) are common.

• 35% to 50% of fits in the elderly are caused by vascular disease.

• 20% of patients with stroke have seizures within the first year.

• Elderly persons are more susceptible to pharmacological causes of fits, e.g. neuroleptics, tricyclics, and to alcohol withdrawal.

• An EEG can be useful but a normal or non-diagnostic EEG does not rule out epilepsy.

• Don’t forget hypoglycaemia as a cause of fits.

• Anti-convulsant drugs should be started after the first fit if a vascular or structural cause is suspected.

• Pallor suggests cardiac cause.

• Tonic–clonic contractions or incontinence suggest epilepsy.

• Was there a history of head turning or tight neckwear? This suggests carotid sinus syndrome.

• Was there a period of drowsiness after blackout? This suggests epilepsy but might also occur in cardiac causes.

Investigations

• FBC, U&Es, glucose, TFTs, Ca2+

• 24-hour tape if ECG abnormal or history suggestive of cardiac cause

• If history suggests epilepsy: EEG, and/or CT scan

• Specialist intervention: carotid sinus massage – undertaken if carotid sinus syndrome suspected (Note: contraindications for massage include presence of carotid bruit or history of carotid territory neurological events)

Cardiovascular causes of blackouts

• Arrhythmias (brady- or tachy-) can be difficult to diagnose and sometimes require repeated 24-h tapes or 2–3-week ‘event recorders’ (see p. 278).

• Myocardial infarction: can be pain free in older people.

• Aortic stenosis: typically causes exertional syncope, also shortness of breath on exertion and angina.

• Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: diagnosed on echocardiogram.

• Carotid sinus syndrome is an underdiagnosed cause of unexplained blackouts. It is caused by an exaggerated response of baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and requires specialist investigation by carotid sinus massage with close observation. There are three variants. The cardioinhibitory variant is diagnosed by > 3-s asystole on massage. The vasopressor variant is diagnosed by a 50-mmHg drop in blood pressure or systolic blood pressure drop to < 90 mmHg. Thirdly, up to one-third of cases are mixed.

• Vasovagal syncope: occasionally presents for the first time in older people. Consider if there is a long history of ‘funny turns’.

Falls in the elderly

What questions should you ask?

• What was he doing when he fell, e.g. was there a postural element?

• What does he remember about the fall?

• What happened immediately before the fall?

• Were there any preceding symptoms?

• Were there any physical hazards, e.g. wet floor, carpet edge?

These features can help distinguish pathological causes (intrinsic) from those with a major external factor (extrinsic), although in practice most falls are multi-factorial. Falls or ‘collapse’ can be seen as a final common pathway for many diseases common in the elderly.

Orthostatic hypotension

This is defined as a > 20-mmHg drop in systolic BP on standing or during head-up tilt:

• Common in elderly: occurs in up to 30% of healthy older people and it is not clear why some develop symptoms.

• ‘Physiological’ changes in elderly: decreased baroreceptor sensitivity increases risk of postural hypotension.

• ‘Pathological’ changes: e.g. sepsis with vasodilatation; poor LV function; neurological disease affecting reflex pathways.

• Pharmacological causes: beta blockers, vasodilators, anti-parkinsonian drugs, sedatives, neuroleptics, diuretics.

Investigations of falls

• BP and heart rate measurement with patient lying flat, with patient standing upright or at 45° on tilt table after 1, 3 and 5 min.

• FBC for evidence of infection, anaemia.

• U&Es, creatinine for evidence of dehydration, renal impairment (eGFR is calculated).

• Blood glucose for hypo-/hyperglycaemia.

• Thyroid function tests for subclinical hypothyroidism.

• ECG for ischaemia, arrhythmias, silent MI.

• Heart beat monitoring (beat-to-beat variation) for autonomic neuropathy.

Management of falls

• Review medications and withdraw exacerbating drugs if possible.

• Treat medical factors, e.g. sepsis.

• Assessment and reduction of osteoporosis risk.

• Advice to patients (see below).

• Drug treatment occasionally used in patients with persistent disabling symptoms:

Delirium (see p. 515)

Delirium in the elderly

As a condition (syndrome) it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Diagnosis

Delirium – diagnostic criteria (derived from DSM-IV-TR)

Confusional assessment method (CAM) criteria

1. Acute onset + fluctuating course: this history is usually obtained from the family/carer or from the nurse caring for a patient already in hospital.

2. Inattention: is the patient easily distractible or does he/she have difficulty keeping track of what is being said?

3. Disorganised thinking: is the patient incoherent? Is the conversation irrelevant?

4. Altered level of consciousness: the patient might be hyperactive, hypoactive/lethargic or semi-conscious.

Remember

• One in four patients with delirium are hypoactive

• Although history/observations can confirm the presence of CAM features, it is also useful to assess the patient’s cognitive functioning using serial mental test scores, e.g. Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT) (Table 7.1). Other tests using questions on: orientation (e.g. time, place, date), registration (naming objects), attention and calculation (simple arithmetic), recall (previously mentioned objects) and language (understanding commands) can be used.

Table 7.1 Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT)

Causes

For causes, remember the mnemonic delirium and think of common conditions:

D drugs: side effects, toxicity of drugs, e.g. hypotensives, sedatives

E electrolyte/endocrine disturbance, e.g. hyponatraemia, hypernatraemia, hypothyroidism

L lack of drugs: withdrawal of drugs

I infections, e.g. pneumonia, cellulitis

R reduced sensory input, e.g. visual impairment

I intracranial: TIAs, epilepsy

U urinary retention/faecal impaction

How would you manage a patient with delirium?

• Treat cause(s) of delirium. Review present drug therapy.

• Environmental measures and general support: fluids/nutrition; bladder/bowel care + environment (nurse in quiet, dimly lit room if possible), providing reassurance and reorientation.

• Pharmacological management: only appropriate if general supportive measures are not adequate to reduce patient’s distress and if there is danger to patient. Drugs of choice:

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.

Inovye SK. Delirium in the older persons. NEJM. 2006;354:1157–1185.

Young J, Inovye SK. Delirium in older people. BMJ. 2007;334:824–826.

Dementia

Definition.

• The capacity to solve problems of day-to-day living.

• The performance of learned perceptuomotor skills.

• The correct use of social skills.

• The control of emotional reactions in the absence of gross clouding of consciousness.

• Dementia is often irreversible and progressive, and has a number of causes.

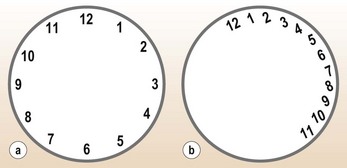

• Assessment: this is performed using the 10-point Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT; Table 7.1), or Clock-drawing test (Fig. 7.1).

• Although screening tests are useful in demonstrating the presence of deficits in cognition, they cannot be used for making the diagnosis of dementia or identifying the underlying cause. This requires imaging (CT or MRI scan) and, in some patients, assessment by a clinical psychologist and/or a psychiatrist. A history of progressive decline in memory or cognition over 6 months is significant.

Causes

The common causes of dementia include Alzheimer’s disease, multi-infarct dementia, Lewy body dementia and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, but other conditions can produce a dementia-like syndrome (Table 7.2) and p. 523.

Table 7.2 Examples of treatable causes of dementia-like syndrome (see also p. 523)

Management

• Alzheimer’s disease (AD): although there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, research on acetylcholine esterase inhibitors has shown that in selected patients with mild to moderate AD the decline can be slowed down. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has produced a guidance on use of donepezil, rivastigmine, memantine and galantamine in patients with mild to moderate AD by specialists. Other agents/drugs that have some benefit to patients with AD include vitamin E and Ginkgo biloba extract.

• Multi-infarct dementia: treat the risk factors, such as hypertension. Aspirin also has a role in preventing further strokes. Ginkgo biloba (120–240 mg daily) can also help.

• As dementia progresses, the management focus changes to care provision for patients plus support for carers.

• Lewy body dementia: avoid anti-psychotics as they can increase confusion. Some of these patients respond to acetylcholine esterase inhibitors.

Depression

Depression is common in old age (see also p. 528). Community studies have revealed a prevalence of 11.3% for depressive symptoms and 3% for depression in the UK. Studies of elderly hospital inpatients have shown that up to 33% have depression. It is common in the elderly with chronic physical illnesses such as stroke, and it can also be the presentation of an occult physical illness such as hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia or carcinoma of the lung. Physical illness is the biggest risk factor for depression in old age.

Case history

Examination showed no abnormality apart from slight residual neurological signs from his CVA.

Assessment

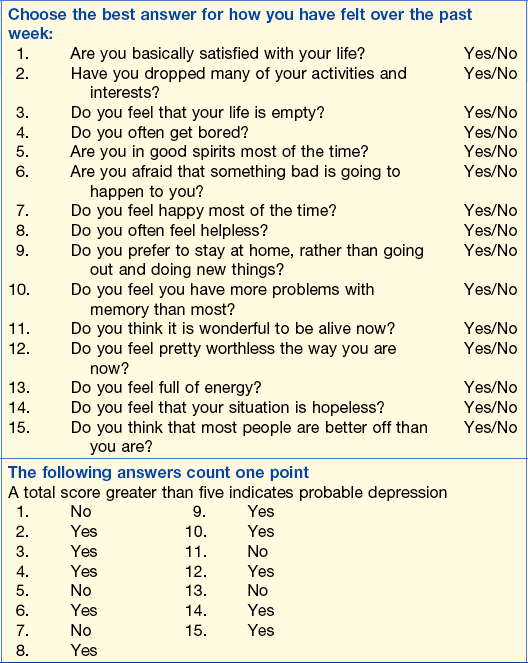

• Geriatric depression scale (Table 7.3) as a screening test. The Geriatric Depression Scale (shorter version) is a reliable and valid screening instrument of depression in the elderly. A score greater than 5 indicates probable depression.

• Physical examination and investigations to detect/exclude physical causes of depression, such as hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, malignancy. In a patient with a normal physical examination it is recommended that FBC, U&Es, LFTs, vitamin B12, Ca2+,  TFTs and chest X-ray are performed.

TFTs and chest X-ray are performed.

In this patient, these blood tests and the CXR showed no abnormality.

Table 7.3 Geriatric Depression Scale

From Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Clinical Gerontologist 1986; 5: 165–173.

Management

• Citalopram: a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) 8–32 mg daily.

• Mirtazapine: a pre-synaptic alpha-2 antagonist is particularly useful in patients with poor appetite – 15 mg daily, increased according to response to 45 mg daily.

• Venlafaxine: a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, 75–150 mg daily.

Severely depressed patients with or without suicidal ideation need urgent referral to a psychiatrist for further assessment.

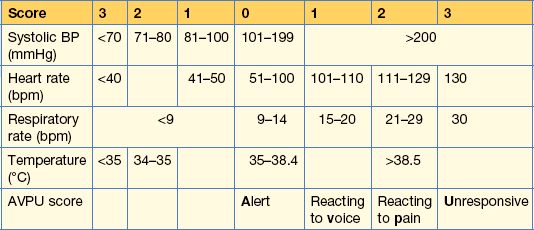

Non-specific presentation of illness in the elderly

These problems are highlighted in the following case. MEWS (Table 7.4) is a simple physiological scoring system that can be used at the bedside in a medical admission unit. It identifies patients at risk of deterioration and who may require more specialised care.

Case history (1)

On arrival in hospital Mr S was very confused and unable to give a detailed history. His abbreviated mental test (AMT) score (see Table 7.1) was 3 out of 10.

It was not clear how long he had been confused or how mobile he had been before these problems.

Progress.

• Any illness in old age can present with any of the so-called ‘giants’ of geriatric medicine, i.e. confusion, falls/instability and incontinence.

• In addition, some illnesses present atypically. Examples of this include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree