Chapter 7 Cardiovascular Diseases

General Considerations

Cardiovascular diseases are the commonest cause of death in Westernised communities. The main forms are:

The following general abnormalities of circulation are common to both.

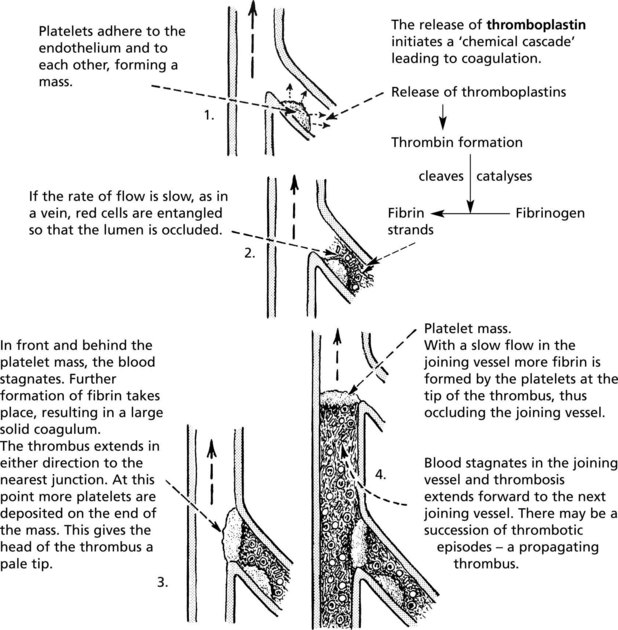

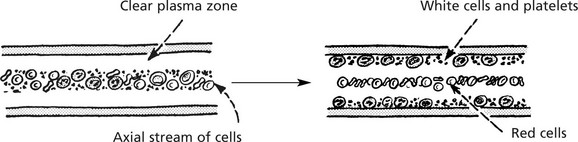

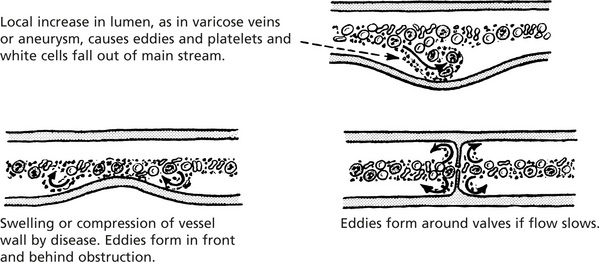

Factors Leading to Thrombosis

The 3 MAIN factors leading to thrombosis are known as Virchow’s triad:

Turbulence, e.g. by deformation of vessel wall or around venous valves.

This leads to platelet adhesion and aggregation. Common causes are:

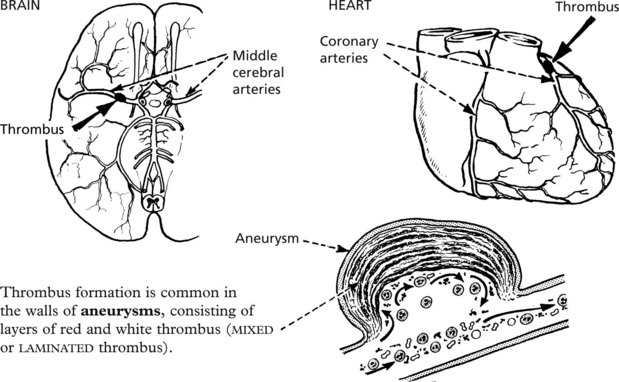

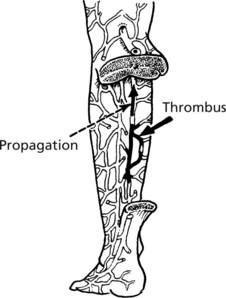

Common Sites and Types of Thrombus

Arterial

Thrombi are common in arteries as a complication of atheroma. Forming in a rapid circulation, the thrombus consists mainly of platelets (white thrombus).

Venous

Bed rest, operations and cardiac disease are predisposing conditions.

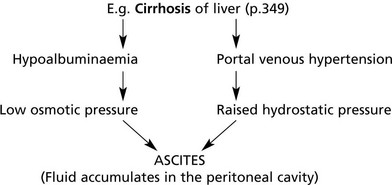

Portal thrombosis is a rare complication of abdominal disease, e.g. hepatic cirrhosis.

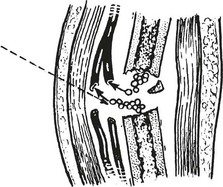

Capillary

Thrombi, composed mainly of fused red cells, form when capillaries are damaged, usually in acute inflammatory processes.

Capillaries are occluded by fibrin thrombi in cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC – see p.414).

Sequels of Thrombosis

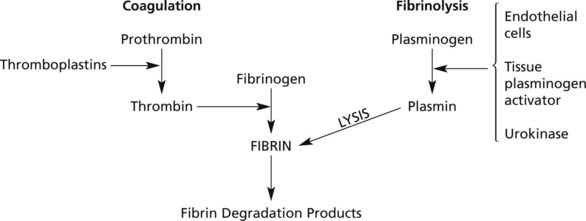

Many small thrombi are completely removed by the Fibrinolytic System which exists to limit thrombosis.

PROPHYLAXIS and THERAPY of thrombosis aims at:

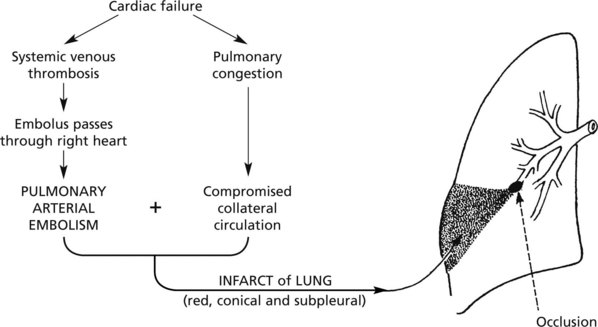

Embolism

An embolus is any abnormal mass of matter carried in the blood stream and large enough to occlude some vessel.

Matter entering the vascular system may be:

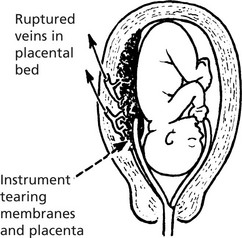

Amniotic Fluid Embolism

During childbirth, amniotic fluid may enter a uterine vein, especially after manipulations. Vernix, hairs and squames enter the circulation. In addition to embolic phenomena, there are also coagulation disorders (p.413).

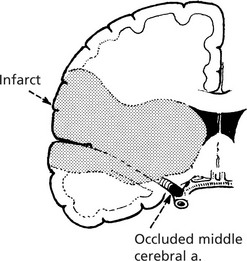

Arterial Obstruction

Arterial obstruction is usually due to thrombosis or embolism and may be (i) partial or complete, (ii) acute or slowly progressive.

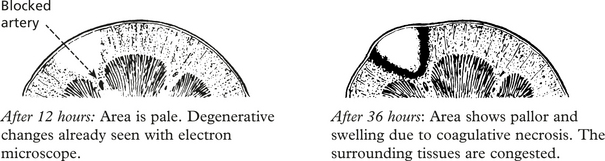

Important Sites of Infarction

Heart (p.175)

Infarction is almost always due to coronary arterial thrombosis complicating atheroma.

If the patient survives, the infarct heals by fibrosis.

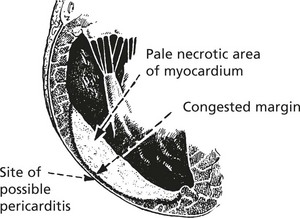

Brain (p.177)

The usual changes of infarction take place, but the necrosis is colliquative – cerebral softening.

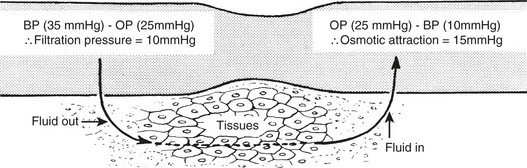

Normal Tissue Fluid Circulation

There is continuous interchange of fluid between blood and tissues. Some fluid enters the lymphatics before eventually returning to the blood stream. Two main forces operate pressure gradients controlling the fluid movement.

Intake via the gut or parenterally may exceed the ability of the kidneys to eliminate water.

Oedema

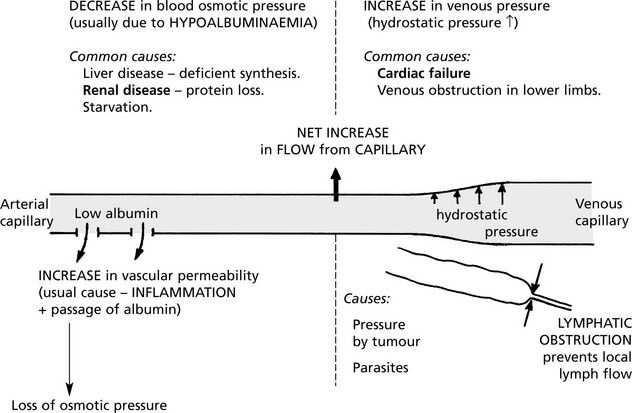

Oedema is an accumulation of excess fluid in the extravascular tissues. It can be local or generalised. There are a wide variety of causes.

More than one factor may apply:

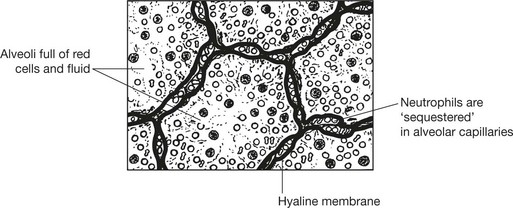

Cerebral (p.532) and pulmonary (p.187) oedema are life threatening and are dealt with separately.

Shock

Shock is a condition in which there is reduced perfusion of the vital organs due to a severe and acute reduction in cardiac output and effective circulating blood volume. There is progressive cardiovascular collapse characterised by hypotension, hyperventilation and clouding of consciousness.

Causes

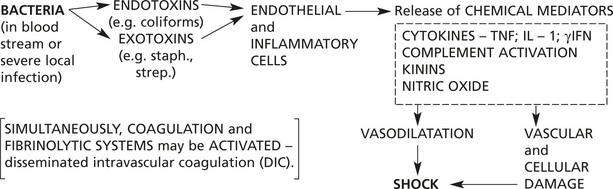

In serious bacterial infections (especially Gram-negative organisms, e.g. E. coli).

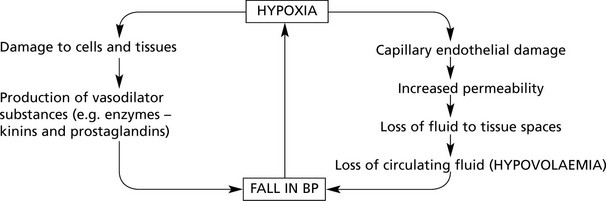

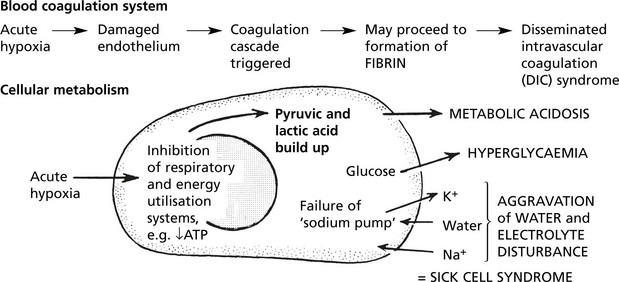

Effects

These two mechanisms combine to cause the shock syndrome.

The main consequences of shock are:

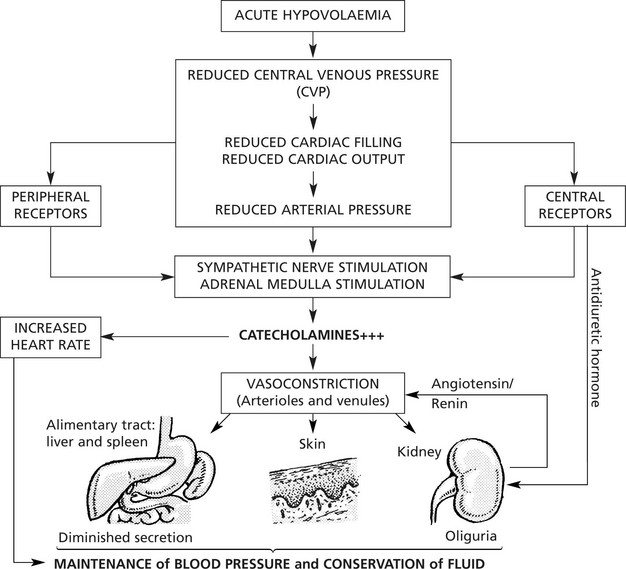

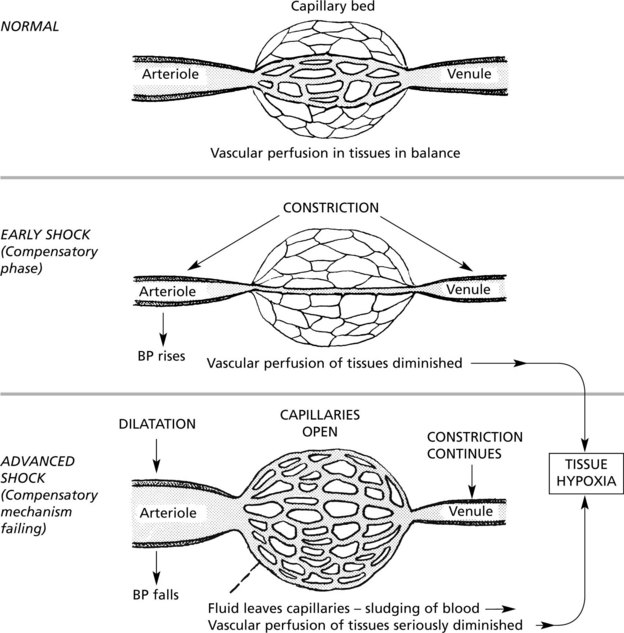

Reactive Circulatory Changes – Early Stage

These changes are concerned with the maintenance of an adequate cerebral and coronary circulation and are effected by redistribution of the blood in the body as a whole.

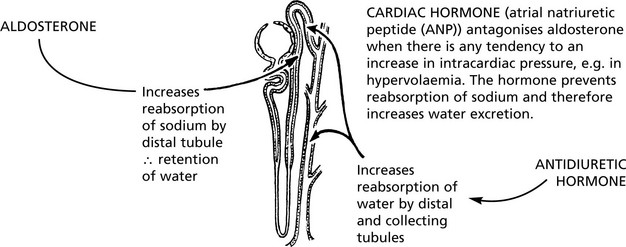

Note: Salt and water are retained due to aldosterone from the adrenal cortex.

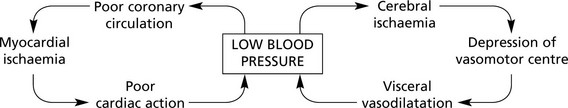

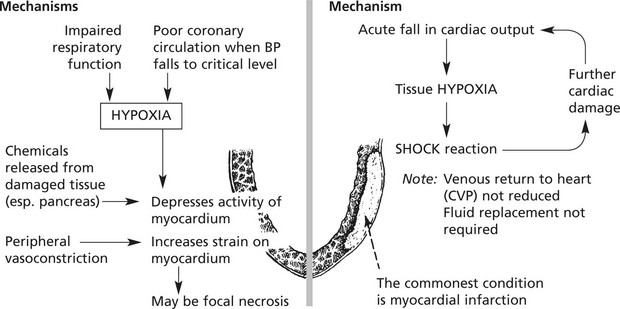

Decompensation – Advanced Stage

The patient is now listless, pale and cold, the face is pinched and the lips blue. The pulse is rapid and weak and the blood pressure is low.

Septic Shock (Endotoxic)

Causes

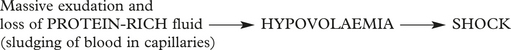

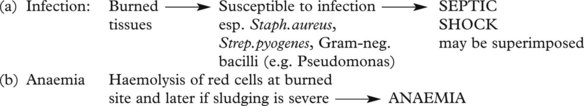

Shock in Burns and Scalds

Shock – Individual Organs

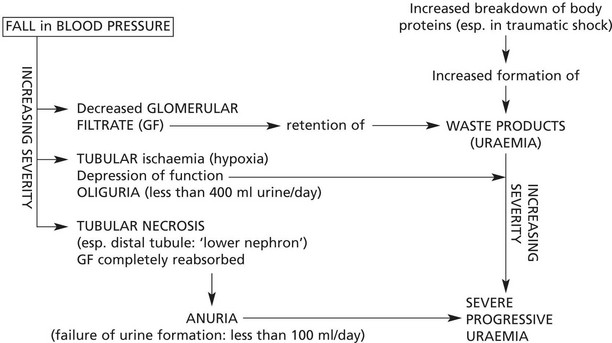

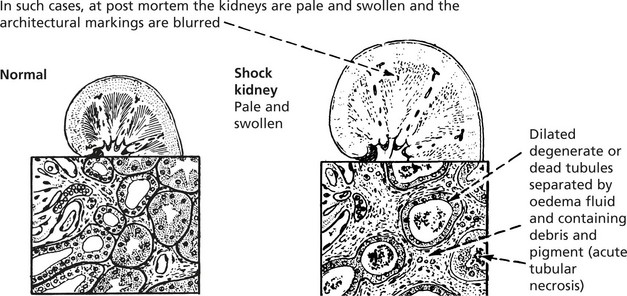

Kidneys

The excretory function of the kidneys is always disturbed in shock. This is due to the general circulatory collapse and hypotension, but it may be aggravated by the secretion of renin and angiotensin by the kidney, aldosterone by the adrenal and antidiuretic hormone by the posterior pituitary. These hormones are secreted in an attempt to retain fluid and restore the blood volume, but by inducing vasoconstriction they will tend to increase renal damage.

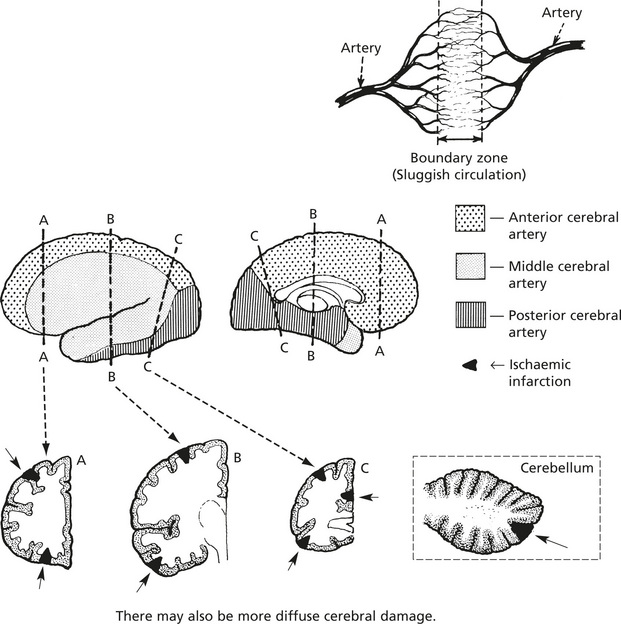

Brain

During the compensated phase of shock, relatively mild cerebral ischaemia is associated with changes in the state of consciousness. When the blood pressure falls to below 50–60 mmHg, the brain suffers serious ischaemic damage with infarction in the ‘boundary zones’ of the cerebral cortex and cerebellum.

Shock – Individual Organs: Outcome

Liver

The liver acinus is supplied by portal venous blood and hepatic arterial blood: in shock, Zone 3 of the hepatic acinus is vulnerable to anoxia.

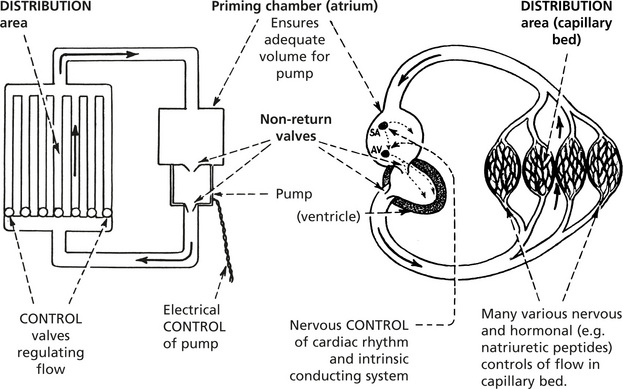

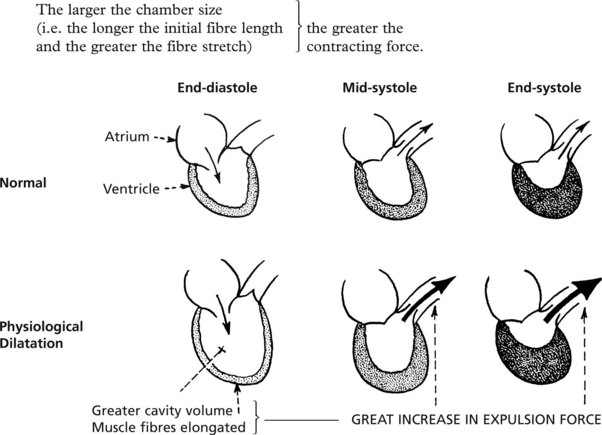

Cardiac Function

The main function of the heart is to provide the pumping action in a closed circulation.

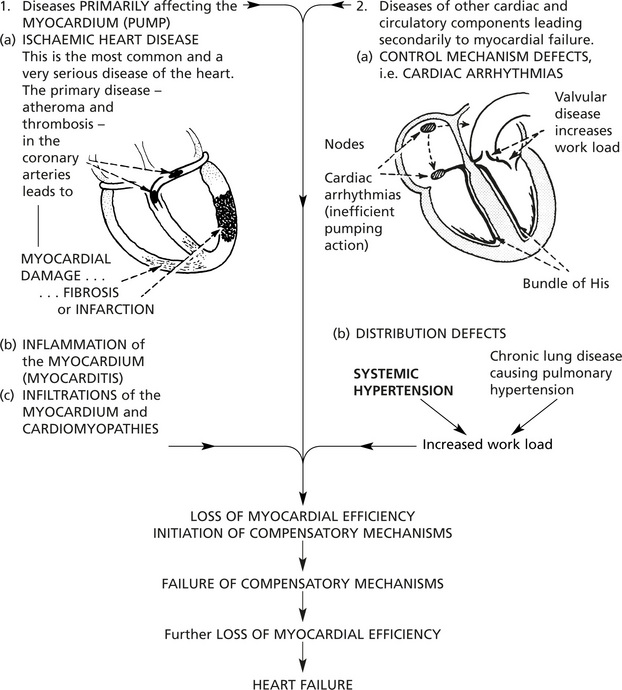

Heart Failure

Heart failure is very common and occurs when the ventricular muscle is incapable of maintaining a circulation adequate for the needs of the body, producing symptoms on exercise and at rest.

Causes of heart failure can be separated into two main groups:

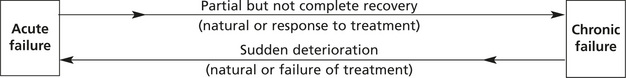

Acute and Chronic

This depends on the suddenness of onset and rate of development.

The causes and effects are different.

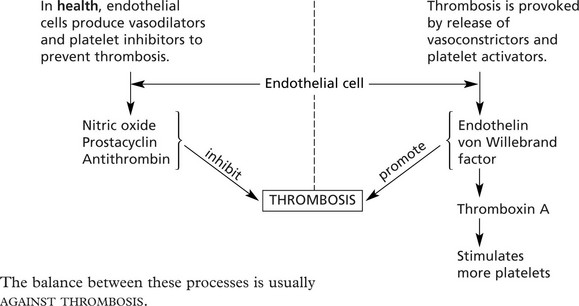

| Acute | Chronic | |

|---|---|---|

| Time factors |  |  |

| Causes | (a) ACUTE CORONARY ARTERIAL OCCLUSION with infarction or arrhythmia (b) Pulmonary embolism (c) Severe malignant hypertension (d) Acute myocarditis (e) Acute valve rupture | (a) Ischaemic heart disease (b) Hypertension (c) Chronic valvular diseases (d) Chronic lung diseases (e) Chronic severe anaemia |

| Effects | SUDDEN DEATH May be no time for compensatory mechanisms to be initiated. Acute pulmonary oedema is common. May be acute ischaemic effects in brain and kidneys. | Compensatory mechanisms fully developed – hypertrophy and dilatation. Chronic oedema and chronic venous congestion. |

Acute and chronic failure are at opposite ends of a spectrum but may merge.

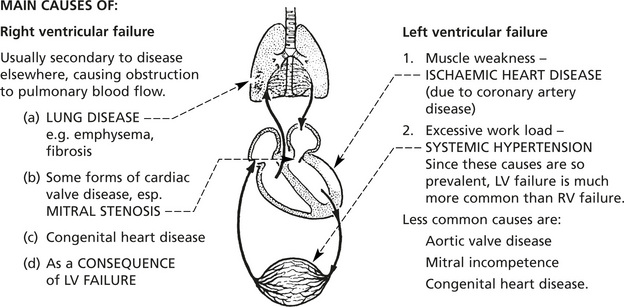

Left, Right and Combined Ventricular Failure

From a clinical point of view it is convenient to consider heart failure as affecting one or other side of the heart.

| The pulmonary circulation | The systemic circulation | |

|---|---|---|

| A low pressure system | A high pressure syste | |

| Systolic arterial pressure = 24 mmHg | Systolic arterial pressure = 120 mmHg | |

| Pressure gradient, artery/vein = 8 mmHg | Pressure gradient, artery/vein = 90 mmHg | |

| Right ventricular mass and coronary blood supply | < 1:4 (approx.) | Left ventricular mass and coronary blood supply |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree