8 Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in the Western world, with most deaths arising from ischaemic heart disease. Although the incidence of ischaemic heart disease is declining in many developed countries, it continues to rise in Eastern Europe and on the Indian subcontinent. Valvular heart disease is also common, but while rheumatic fever still predominates in the Indian subcontinent, degenerative disease of the aortic valve is now the leading aetiology in developed nations. The diversity of symptoms attributable to heart disease is limited and patients often remain asymptomatic despite the presence of advanced disease. However, prompt recognition of the development of heart disease is important, as many highly effective and evidence-based treatments are available.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

A close relationship between symptoms and exercise is a hallmark of cardiovascular disease. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification is often used to grade disability (Box 8.1).

8.1 NEW YORK HEART ASSOCIATION (NYHA) FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATION ![]()

| Class I | No limitation during ordinary activity |

| Class II | Slight limitation during ordinary activity |

| Class III | Marked limitation of normal activities without symptoms at rest |

| Class IV | Unable to undertake physical activity without symptoms; symptoms may be present at rest |

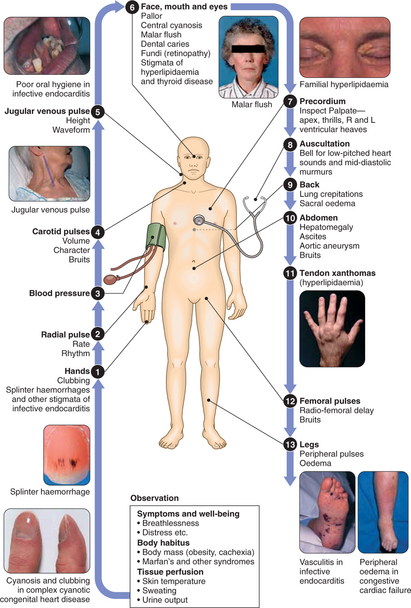

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

BREATHLESSNESS (DYSPNOEA)

The differential diagnosis of dyspnoea is wide and includes many respiratory disorders (p. 271). However, both acute and chronic dyspnoea may have a cardiac aetiology. Acute left heart failure with pulmonary oedema is a common cause of the former. With pulmonary oedema:

SYNCOPE AND PRESYNCOPE

Cardiovascular disorders that cause an abrupt fall in cerebral perfusion may lead to recurrent or isolated episodes of syncope (sudden loss of consciousness) and presyncope (lightheadedness and near-collapse). Other causes of blackouts and ‘funny turns’ include seizure, hyperventilation and hypoglycaemia; dizziness, in the form of vertigo, may also result from labyrinthine or central vestibular dysfunction (p. 619). An accurate description of events from the patient and a witness is invaluable and helps to guide investigations. In cardiac syncope (i.e. secondary to arrhythmia or structural heart disease), onset is usually sudden and recovery rapid. In contrast, patients with vasovagal syncope often feel nauseated and unwell for several minutes before and after the episode. Patients with seizures may exhibit abnormal movements, usually take many minutes to recover and are confused on recovery.

Arrhythmias: May cause lightheadedness or blackouts, the latter with profound bradycardia or malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Ambulatory ECG recordings may establish the diagnosis, although a close temporal relationship must be demonstrated between symptoms and a recorded arrhythmia. Patient-activated ECG recorders are useful for patients with recurrent dizziness but clearly unhelpful in sudden collapse. Where necessary, an implantable ‘loop recorder’ can be placed beneath the skin of the upper chest under local anaesthesia. This device continuously records an ECG, storing arrhythmic events in its digital memory for subsequent analysis.

PALPITATION

The term ‘palpitation’ may be used to describe a variety of sensations, including an erratic, fast, slow or forceful heart beat. A detailed description is essential (Box 8.2) and patients should be asked to tap out the heart beat on the table.

8.2 THE EVALUATION OF PALPITATION ![]()

An ECG recording during an attack of palpitation (ambulatory monitoring or patient-activated recorder) may be necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. Most cases are due to an awareness of the normal heart beat, sinus tachycardia or benign extrasystoles triggered by stress, intercurrent illness, caffeine or alcohol. In such cases, careful explanation and reassurance will often suffice but a low-dose β-blocker may be helpful in patients with distressing symptoms. Arrhythmia management is described on pages 215–225.

ABNORMAL HEART SOUNDS AND MURMURS

The first clinical manifestation of heart disease may be the incidental discovery of an abnormal sound on auscultation. Clinical evaluation is helpful (Box 8.3) but an echocardiogram is often necessary to confirm the nature of an abnormal heart sound or murmur. Some added sounds are physiological but may also occur in pathological conditions; for example, a third sound is common in young people and in pregnancy but is also a feature of heart failure. Similarly, an ejection systolic murmur may occur in hyperdynamic states (e.g. anaemia, pregnancy) but also in aortic stenosis. Benign murmurs do not occur in diastole and systolic murmurs that radiate or are associated with a thrill are almost always pathological. Individual murmurs are dealt with below (pp. 254–260).

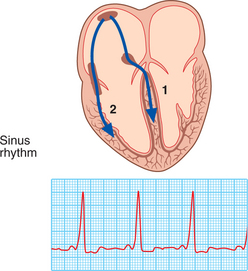

DISORDERS OF HEART RATE, RHYTHM AND CONDUCTION

ATRIAL TACHYARRHYTHMIAS

Atrial tachycardia: Produces a narrow complex tachycardia with abnormal P-wave morphology caused by increased atrial automaticity, sinoatrial disease or digoxin toxicity. It may respond to β-blockers, which reduce automaticity, or class I or III anti-arrhythmic drugs (p. 760).

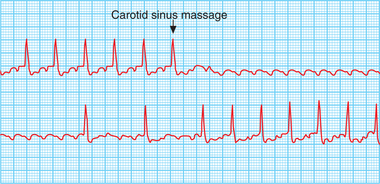

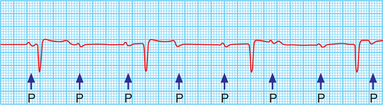

Atrial flutter: Results from a large re-entry circuit within the right atrium. The atrial rate is approximately 300/min, but associated 2 : 1, 3 : 1 or 4 : 1 atrioventricular (AV) block usually produces a ventricular heart rate of 150, 100 or 75/min. The ECG shows saw-toothed flutter waves. With regular 2 : 1 AV block these may be buried in the QRS complexes and T-waves but can be revealed by transiently increasing the degree of AV block through carotid sinus massage (Fig. 8.1) or i.v. adenosine. Digoxin, β-blockers or verapamil can limit the ventricular rate but electrical or chemical cardioversion is often preferable. In addition to restoring sinus rhythm, flecainide, amiodarone or propafenone may prevent recurrent episodes of atrial flutter, though catheter ablation is now the treatment of choice for patients with persistent and troublesome symptoms.

ATRIAL FIBRILLATION (AF)

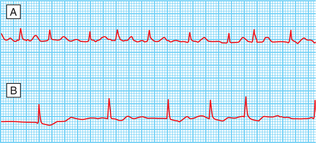

AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, its prevalence rising with age. The atria beat rapidly, but in an uncoordinated and ineffective manner. The ventricles are activated irregularly at a rate determined by conduction through the AV node, giving rise to an ‘irregularly irregular’ pulse. The ECG (Fig. 8.2) shows normal but irregularly spaced QRS complexes with absent P waves.

Initially, classification may be difficult but paroxysmal AF often becomes permanent with progression of the underlying disease process. Common causes of AF are shown in Box 8.4; however, many patients have ‘lone atrial fibrillation’ where no underlying cause is identified.

Management of an acute episode

Within 48 hrs of AF onset, heparinisation and cardioversion with a synchronised DC shock or drug therapy (flecainide or amiodarone) can be attempted. Beyond 48 hrs, the ventricular rate should be controlled and cardioversion deferred until anticoagulation with warfarin (INR 2–3) has been established for at least 3 wks. When AF complicates an acute illness (e.g. chest infection), treatment of the primary disorder usually restores sinus rhythm. All patients with haemodynamic compromise (e.g. hypotension) should receive immediate i.v. heparin and DC cardioversion.

Long-term management

Rhythm control—prevention of recurrent episodes: Treatment with amiodarone or β-blockers may reduce risk of recurrence following successful cardioversion; if relapse occurs, a repeat cardioversion may be appropriate. In paroxysmal AF, β-blockers are usual first-line therapy, especially in patients with associated ischaemic heart disease, hypertension or cardiac failure. Amiodarone is more effective in preventing AF but its use is limited by side-effects. Class Ic drugs such as flecainide, though effective, should be avoided in patients with coronary disease or LV dysfunction. Digoxin and verapamil limit ventricular rate in AF but do not prevent episodes. Radiofrequency ablation is a promising treatment for lone paroxysmal AF.

Prevention of thromboembolism: Left atrial dilatation and loss of contraction cause stasis of blood and may lead to atrial thrombus formation, predisposing patients to stroke and other systemic embolic events. Warfarin (target INR 2.0–3.0) reduces the risk of stroke by two-thirds (with an annual risk of bleeding of 1–1.5%), while aspirin reduces it by only one-fifth. Warfarin is indicated for patients with AF and specific risk factors for stroke (Box 8.5). Patients <65 yrs with no evidence of structural heart disease have a very low risk of stroke and can receive aspirin. With intermittent AF, the risk of stroke depends on the frequency and duration of AF episodes; patients with frequent, prolonged (>24-hr) episodes should be considered for warfarin. Anticoagulation with warfarin should be maintained for at least 1 mth following successful cardioversion.

‘SUPRAVENTRICULAR’ TACHYCARDIAS

AV NODAL RE-ENTRY TACHYCARDIA (AVNRT)

ATRIOVENTRICULAR RE-ENTRANT TACHYCARDIA (AVRT) AND WOLFF–PARKINSON–WHITE SYNDROME

An abnormal band of rapidly conducting tissue (‘accessory pathway’) connects the atria and ventricles. In around half of cases, premature activation of ventricular tissue via the pathway produces a short PR interval and a ‘slurring’ of the QRS complex, called a delta wave (Fig. 8.4). As the AV node and bypass tract have different conduction speeds and refractory periods, a re-entry circuit can develop, causing tachycardia; when associated with symptoms, the condition is known as Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.

VENTRICULAR TACHYARRHYTHMIAS

VENTRICULAR ECTOPIC BEATS (EXTRASYSTOLES, PREMATURE BEATS)

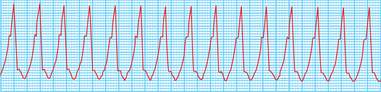

VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA (VT)

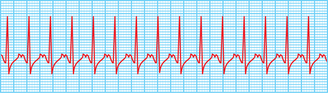

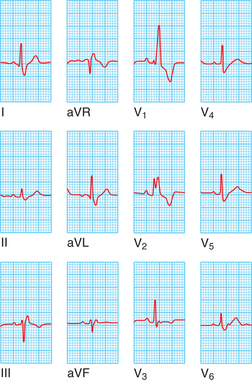

VT usually occurs in patients with coronary heart disease or cardiomyopathies and may cause haemodynamic compromise or degenerate into ventricular fibrillation (p. 221). The ECG shows tachycardia with broad, abnormal QRS complexes and a rate >120/min (Fig. 8.5). VT is by far the most common cause of a broad-complex tachycardia but may be difficult to distinguish from supraventricular tachycardia with bundle branch block or Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome. When there is doubt, it is safer to manage the problem as VT.

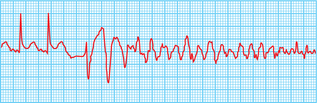

CARDIAC ARREST

VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION (VF) AND PULSELESS VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA (VT)

These rhythms frequently arise in patients with MI or a history of previous MI.

Defibrillation restores cardiac output in >80% of patients if delivered immediately.

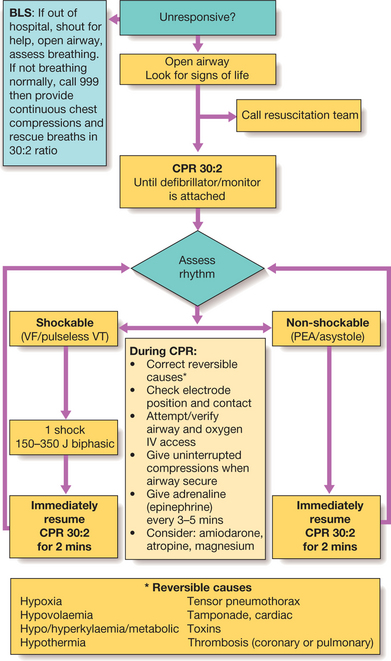

MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST

The management of cardiac arrest is shown in Figure 8.7.

Fig. 8.7 Algorithm for basic and adult advanced life support. For further information see www.resus.org.uk. (BLS = basic life support; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA = pulseless electrical activity; VF = ventricular fibrillation; VT = pulseless ventricular tachycardia)

In the absence of an identifiable, treatable cause (e.g. ischaemia, aortic stenosis), survivors of VT or VF arrest should be considered for anti-arrhythmic therapy or an implantable cardiac defibrillator (p. 226). • Patients who survive cardiac arrest in the context of acute MI require no specific additional treatment.

BRADYARRHYTHMIAS

ATRIOVENTRICULAR (AV) BLOCK

AV block may be congenital or result from:

First-degree AV block

AV conduction is delayed, producing a prolonged PR interval (>0.20 secs). It rarely causes symptoms.

Second-degree AV block

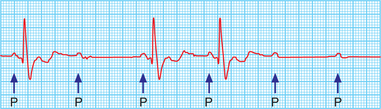

Mobitz type II block (Fig. 8.8): The PR interval of conducted impulses remains constant but some P waves are not conducted. It is usually caused by disease of the His–Purkinje system and carries a risk of asystole. In 2 : 1 AV block alternate P waves are conducted, so it is impossible to distinguish between Mobitz type I and type II block.

Third-degree (complete) AV block

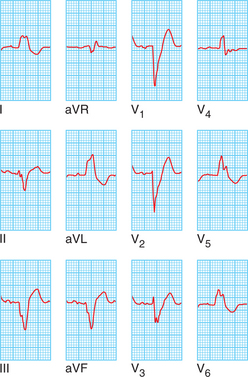

AV conduction fails completely, the atria and ventricles beat independently (AV dissociation, Fig. 8.9), and ventricular activity is maintained by an escape rhythm arising in the AV node or bundle of His (narrow QRS complexes) or the distal Purkinje tissues (broad QRS complexes). Distal escape rhythms are completely regular but slower and less reliable. Cannon waves may be visible in the neck, and the intensity of the first heart sound varies due to the loss of AV synchrony.

Stokes–Adams attacks

Episodes of ventricular asystole may complicate complete heart block, Mobitz type II second-degree AV block and sinoatrial disease, resulting in recurrent syncope (‘Stokes–Adams’ attacks). Episodes are characterised by a sudden loss of consciousness, typically without warning, which may result in a fall. Convulsions (due to cerebral ischaemia) can occur if asystole is prolonged. There is pallor and a death-like appearance during the attack, but when the heart starts beating again there may be a characteristic flush. In contrast to epilepsy, recovery is rapid.

BUNDLE BRANCH BLOCK AND HEMIBLOCK

Interruption of the right or left branch of the bundle of His delays activation of the corresponding ventricle, broadens the QRS complex (≥0.12 secs) and produces characteristic alterations in QRS morphology (Figs 8.10 and 8.11). Right bundle branch block (RBBB) can be a normal variant but left bundle branch block (LBBB) usually signifies important underlying heart disease (Box 8.6).

THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURES

IMPLANTABLE CARDIAC DEFIBRILLATORS (ICDs)

These devices sense rhythm and deliver current through leads implanted in the heart via the subclavian or cephalic vein. They automatically sense and terminate life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. ICDs have all of the functions of a pacemaker (to deal with bradycardias) but in addition can treat ventricular tachyarrhythmias using overdrive pacing, synchronised cardioversion, or defibrillation. ICD implantation is subject to similar complications as pacemaker implantation (see below). Indications for ICDs are shown in Box 8.7.

TEMPORARY AND PERMANENT PACEMAKERS

Permanent pacemakers

Permanent pacemakers utilise the same principles but the pulse generator is implanted under the skin. Electrodes can be placed in the right ventricular apex, the right atrial appendage or both (dual-chamber). Atrial pa-cing may be appropriate for patients with sinoatrial disease without AV block. In dual-chamber pacing the atrial electrode can be used to detect spontaneous atrial activity and trigger ventricular pacing, thereby preserving AV synchrony and allowing the ventricular rate to increase together with the atrial rate during exercise, leading to improved exercise tolerance. A code is used to signify the pacing mode (Box 8.8). Most dual-chamber pacemakers are programmed to a mode termed DDD. Rate-responsive pacemakers trigger a rise in heart rate in response to movement or increased respiratory rate and are used in patients unable to mount an increase in heart rate during exercise. Early complications of permanent pacing include:

8.8 INTERNATIONAL GENERIC PACEMAKER CODE ![]()

| Chamber paced | Chamber sensed | Response to sensing |

|---|---|---|

| O = none | O = none | O = none |

| A = atrium | A = atrium | T = triggered |

| V = ventricle | V = ventricle | I = inhibited |

| D = both | D = both | D = both |

CORONARY HEART DISEASE (CHD)

Hypercholesterolaemia: The risk of CHD and other atherosclerotic vascular disease rises with plasma cholesterol concentration, especially the ratio of total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. A weaker correlation exists with plasma triglyceride concentration. Lowering low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and total cholesterol concentrations reduces the risk of cardiovascular events.

STABLE ANGINA

Clinical features

The history is by far the most important factor in making the diagnosis of stable angina (p. 209). The condition is characterised by central chest pain, discomfort or breathlessness that is precipitated by exertion or other forms of stress, and is promptly relieved by rest. Physical examination is frequently negative but may reveal evidence of:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree