10 Cardiology

Syncope

What are the key questions in establishing the diagnosis?

• Reliable eye-witness account: if not available, make a phone call to the patient’s workplace.

• Prodromal symptoms: non-specific but almost always present for some minutes before a vasovagal attack (faint).

• Precipitating cause: anything from the sight of blood to a hangover!

• Circumstance of event, frequently in:

In the absence of any abnormal investigations, the most likely diagnosis is vasovagal syncope (see Table 15.8, Features of fits and faints). You should be aware of some other specific forms of vasovagal syndrome:

• Carotid sinus syncope: on turning head or shaving the chin. Due to carotid sinus hypersensitivity, usually in the elderly.

• Cough syncope: after a paroxysm of coughing, usually in a patient with obstructive airways disease.

• Micturation syncope: more common in men. Usually occurs in the night when going to pass urine or during micturation itself.

What is the differential diagnosis?

There are many other causes of syncope and all might need to be excluded.

• Neurological: seizures, cerebrovascular disease (TIA, CVA or vertebrobasilar ischaemia) are the most common causes. A good eye-witness account is key to the diagnosis. Note: Some jerky movements of the limbs, and even incontinence, can occur in a prolonged vasovagal attack, especially if the patient remains upright.

• Hyperventilation/anxiety (if suspected, symptoms can often be readily reproduced by voluntary hyperventilation): usually associated with a tachycardia. The patient often has symptomatic palpitations and might feel light-headed, a feeling of being distanced from the surroundings, chest pain and/or paraesthesiae with numbness in arms, hands or lips. Pallor and peripheral cyanosis can be striking in a full-blown attack. Circumstances provoking an attack can often be the same as for a faint (e.g. warm room, stressful situation).

• Orthostatic hypotension: especially in elderly patients. This is often caused by drugs, e.g. for hypertension, but don’t forget autonomic neuropathy and Parkinson’s disease.

A cardiac cause of syncope should be sought in all patients with known structural heart disease.

Investigation

This patient required further investigation as the LBBB indicates cardiac disease.

Treatment and progress

A DDD pacing system (see p. 278) was implanted and programmed to produce a tachycardic response to counter any detected bradycardia of sudden onset. So far she has had no more syncopal attacks.

A clinical approach to patients with tachycardia

1. What is the heart rate? – i.e. 180 beats/min in this man

3. Are the ECG complexes broad or narrow?

Having answered these questions, you should decide who needs admission to hospital (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Patients with tachycardia: who to admit to the Medical Assessment Unit?

| Broad complex | Narrow complex | |

|---|---|---|

| Collapsed | Usually need immediate cardioversion and must be admitted from A&E. Do not give verapamil or other negatively inotropic drugs | Usually need admission into hospital, especially if the patient is in heart failure |

| Did not collapse | The most difficult category to sort out | Can probably go home if tachycardia stops on treatment (Case 1) |

| Probably need admission to sort out diagnosis | Need outpatient assessment | |

| Irregular tachycardia in this group may be due to WPW with AF, so do not give verapamil | If this is a recurrent problem they need to be referred to a cardiologist to be considered for EPS, as they may benefit from radiofrequency ablation of their pathway or their arrhythmia focus |

AF, atrial fibrillation; EPS, electrophysiological studies; WPW, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.

• Always assume a broad complex tachycardia is VT until proved otherwise.

• If in doubt use DC cardioversion rather than drugs.

• Seek advice if your first drug does not work.

• Beware of verapamil (which should not be used as first-line therapy) and other negatively inotropic drugs.

• Check the electrolytes and correct them appropriately before using drugs, but do not delay treatment in a patient who is compromised because you are waiting for results. Remember in an emergency, K+ levels can be roughly measured using blood gas machines in A&E and used to guide replacement therapy.

The ECG and classification of tachycardias

SVT

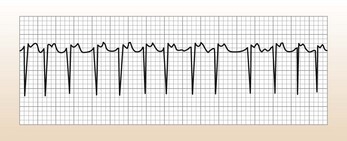

These are narrow complex tachycardias (Fig. 10.1), unless there is bundle branch block. Adenosine is very useful for their diagnosis and will terminate some SVTs:

• Atrial tachycardia: an SVT from a focus in the atrium, rather than due to re-entry.

• Atrial flutter (Afl): look for regular rhythm, often with a rate of 150. Adenosine will help in the diagnosis, often revealing underlying flutter waves.

• Atrial fibrillation (AF): look for lack of P waves, irregular rhythm and baseline; this can be very hard to see with very fast rates, in which case adenosine will help.

Features suggesting that a tachycardia might be an SVT

• Normal LBBB or RBBB morphology but be careful: VT from RV outflow tract with LBBB morphology can look like SVT. A small stubby R wave in V1–2 is characteristic of VT.

• You might be able to see evidence of both atrial and ventricular activity. A constant relationship between the P waves and the QRS complexes suggests a supraventricular origin.

• The frontal and horizontal QRS axes are in the same general direction as that in sinus rhythm.

• It slows with manoeuvres designed to increase vagal tone, e.g. carotid sinus massage.

• If the onset is witnessed you might see a P wave that is premature.

Management

Case history (2)

A 57-year-old woman presents with a tachycardia at a rate of 132 per minute.

On examination she is hypotensive (90/50), looks pale and distressed and has bibasal crackles.

Diagnosis.

This is broad complex tachycardia with gross axis deviation, probably VT (see Table 10.2). She needs urgent treatment ( see below).

Table 10.2 Distinction between supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with bundle branch block and ventricular tachycardia (VT)

Ventricular tachycardia (VT)

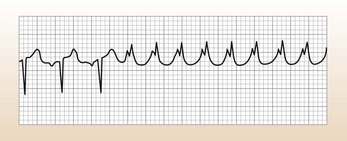

This causes a broad complex regular tachycardia (Fig. 10.2), often called monomorphic VT. However, a broad complex pattern can be caused by any tachycardia if there is a pre-existing abnormality of the conduction system (usually bundle branch block). So, for example, AF with bundle branch block can cause a broad complex tachycardia that is irregular. Although adenosine (see below) can be useful for diagnostic purposes, do not waste time using it if the patient is compromised.

Features suggesting that a tachycardia might be a VT

• A QRS duration of > 140 ms strongly suggests a ventricular origin.

• The frontal and horizontal axes are grossly discordant with that seen in sinus rhythm. Most people are used to looking at the frontal QRS axis in the limb leads. The horizontal axis is estimated by seeing where the predominantly negative QRS complexes become equiphasic as you look across from V1 towards V6. This equiphasic point is called the zone of transition and is usually at V3 or V4. In VT there might be no transition zone or it might be far to the right, or left, of V4.

• QRS morphology: the pattern is not typical of LBBB or RBBB. These are specific appearances that strongly suggest VT, e.g. concordance; seek help if unsure.

• Fusion beats: these are beats where there is simultaneous activation of the ventricles from a focus of arrhythmia and from the atria via the AV node at the same time. These beats will look like a cross between the standard VT complex and the patient’s normal complexes in sinus rhythm.

• Capture beats: occasionally the atria ‘captures’ a normal complex in the midst of a tachycardia.

• You might be able to see evidence of both atrial and ventricular activity. If there is no constant relationship between the P waves and the QRS complexes it suggests a ventricular origin and this is called atrioventricular dissociation.

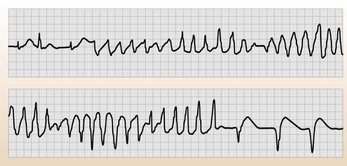

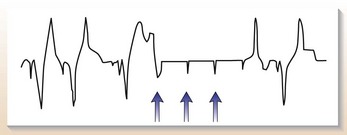

A word about torsade de pointes

Torsade de pointes is an uncommon form of VT with a characteristic ECG pattern (often called polymorphic VT (Fig. 10.3)). The complexes appear to twist around the baseline by virtue of their changes in amplitude. It is particularly associated with syndromes involving a long QT interval. Correct diagnosis of torsade de pointes is necessary because the treatment is very different from VT and treating the underlying cause can often have a marked effect.

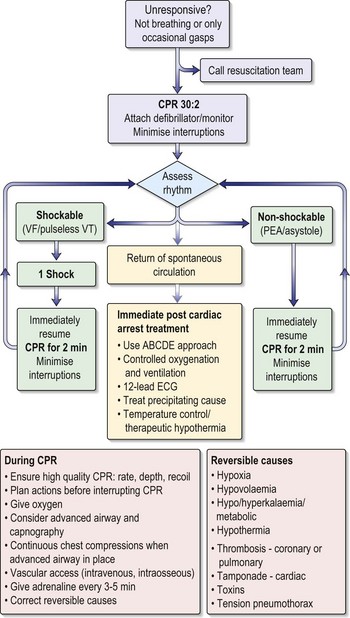

The acute treatment of arrhythmias

Remember

Always think about the underlying state of the ventricle when treating an acute arrhythmia.

Problems with the use of any anti-arrhythmic drugs:

• Many arrhythmias arise as a result of pre-existing LV disease. You need to be aware of any drugs that you give which could further suppress LV function and make matters worse.

• A drug that is ineffective for the rhythm in question might also depress ventricular function without alleviating the rate-related stress on the ventricle.

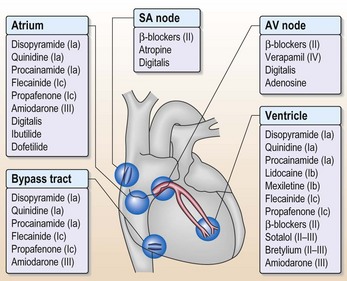

• The final catch when you are treating arrhythmias with drugs (Fig. 10.4) is that ischaemia might alter the electrophysiological activity of drugs. This means that drugs that are anti-arrhythmic under normal circumstances become pro-arrhythmic in ischaemic myocardium.

This limits the use of drugs in many patients because it is often difficult to exclude the possibility of coexisting ischaemia. Because of these problems it is often safer to use DC cardioversion than drugs.

Figure 10.4 Drugs used to treat arrhythmias. The numbers in brackets refer to the Vaughan–Williams classification.

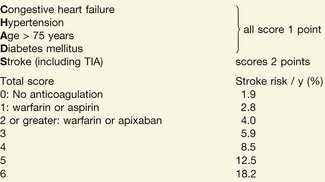

Atrial fibrillation

Should I cardiovert?

Yes, generally DC cardioversion is always worth trying at least once, provided there are no contraindications. Cardioversion can also be achieved with drugs but do not forget there is nearly as much of a risk of a thromboembolic event as with DC cardioversion, so these patients should be appropriately anti-coagulated. Amiodarone (200 mg × 3 daily for 1 week then 200 mg maintenance per day) and class 1c drugs (e.g. flecainide) both promote cardioversion. Figure 10.4 shows the sites of action of drugs on the heart but do not use flecainide in the presence of ventricular disease.

Bradycardia and pacing

• Sinus node: sick sinus syndrome

• AV node: complete heart block, slow atrial fibrillation

• His–Purkinje system: bifascicular block (left axis deviation and right bundle branch block; RBBB).

Diagnosis

• Difficulties often arise in establishing arrhythmia as a cause of dizzy spells when the condition is intermittent, as it often is in the early stages.

• 24-h ECG is the best investigation but repeat tapes might be needed to demonstrate an abnormality when the history is very suggestive. Occasionally, in a patient with persistent symptoms and no findings on repeat ambulatory ECG monitoring, an implantable ECG recording device can help.

Classification of generic pacemaker code

Notation is by the following abbreviations:

• Chamber paced (0 = none, A = atrial, V = ventricular, D = both or dual).

• Chamber sensed (0 = none, A = atrial, V = ventricular, D = both or dual).

• Response to sensing (0 = none, I = inhibited, T = triggered, D = both T + I).

• Rate response (0 = none, R = rate modulation).

• Anti-tachycardia function (0 = none, P = anti-tachycardia pacing, S = shock, D = pace and shock).

For example: VVI = ventricular pacing, ventricular sensing, inhibition of pacing when beat is sensed; DDD(R) = dual pacing, dual sensing, inhibition and triggered as appropriate when beat is sensed, rate response mode available.

Pacemakers in common use

Rate response (R) is used when a patient has lost the chronotropic response, i.e. cannot increase the heart rate with exercise/stress. The cardiologist inserting the pacemaker will decide this but will need to know the patient’s usual level of activity/independence to make this decision. AAI pacemakers are not often used in practice because a small proportion of these patients go on to develop coexisting AV nodal disease, so in anticipation of this dual-chamber pacemakers are usually implanted.

Pacemaker problems

Technical problems

• Fibrosis occurring around the pacemaker tip: this can cause pacemaker thresholds to rise, which can affect pacemaker function.

• Lead displacement: this will cause pacemaker malfunction, usually manifesting as failure to capture. It is most common in the first 6 weeks after implantation.

• Lead or pacemaker erosion through the skin: usually occurs long term.

• Pacemaker syndrome: vague feelings of weakness or dizziness in patients with VVI pacemakers and complete heart block. This is caused by loss of synchrony between atrial and ventricular contraction leading to episodic falls in BP and retrograde conduction of pacing impulse from ventricle to atria leading to simultaneous atrial and ventricular contraction. It is not seen with dual-chamber pacing and is treated by upgrading to a dual-chamber system.

Case history (2)

A 78-year-old man is admitted for a routine hip replacement. You are fast bleeped to the Orthopaedic ward; when you arrive the orthopaedic SHO tells you the patient is in ‘VT’. You rush to see the patient, who is sitting up reading his newspaper. His rhythm strip from his preoperative ECG is shown (Fig. 10.5). What do you tell the SHO and what do you do?

• This is a paced rhythm but there is evidence of failure to capture.

• You ask the pacing clinic to check his pacemaker; they find that the sensing threshold has risen but all other parameters are fine. They increase his pacemaker output and his pacemaker function returns to normal.

Remember

• Bradycardia and even transient conduction disturbance (first-degree and Mobitz type I or Wenckebach) can occur in healthy people during sleep. Great caution is needed when interpreting rhythm disturbances at night.

• Always take dizzy spells in a patient with a pacemaker seriously. Formal evaluation and an urgent pacing clinic check are required.

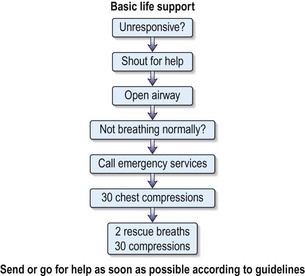

Cardiac arrest and basic life support

What should you do?

An assessment and initial resuscitation of the critically ill patient should be undertaken (ABCDE):

• Airway – remove any obstructing material and make sure airway is clear.

• Breathing – look, listen and feel for signs of breathing.

• Circulation – check carotid and peripheral pulses and start external chest compression if cardiac arrest.

• Disability – conscious level – Glasgow Coma Scale (see Table 15.3, p. 492).

• Examination/exposure. – to allow a full examination to be carried out.

Recent evidence emphasises that maintaining the circulation is the key factor overall.

The order of resuscitation should be CAB, i.e. Circulation, Airways, Breathing.

• Check for danger then shake and shout to check responsiveness.

• If there is no response shout for help.

• If no one responds to your call open the airway (Fig. 10.6).

There are no signs of breathing, you remain alone. What must you do now?

You must leave the patient and go to the nearest telephone to initiate the cardiac arrest call.

You have initiated the emergency call from a telephone further along the corridor.

What should be your next action?

There are no signs of circulation after your assessment. The patient is cyanosed and motionless.

Commence basic life support (see Fig. 10.6).

Chest compressions – carefully note the following:

• Hand position: place the heel of the hand on the sternum, two fingers’ breadth above where the rib margins meet.

• Arm position: lock the elbows and lean directly over the porter.

• Rate: aim to maintain a rate of 100 per minute.

• Depth: compress the chest one-third of the resting diameter of the chest.

• CPR at a ratio of 30 : 2 (30 compressions to 2 breaths), irrespective of number of rescuers.

• Continue this until the defibrillator arrives (Fig. 10.7).

Progress.

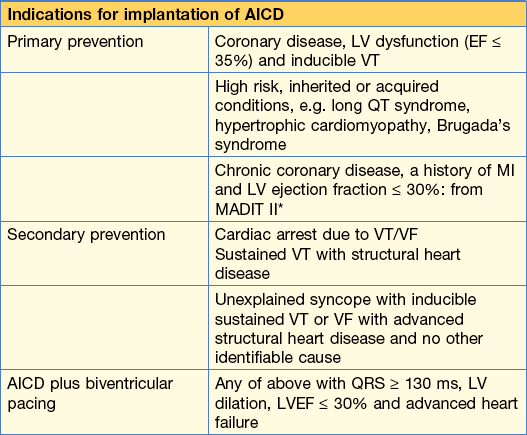

He will need investigations to rule out structural heart disease (echo and angiogram). He will then need electrophysiological studies and an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD; Table 10.3) implanted to prevent recurrence because he has, in effect, had an ‘out of hospital’ VF arrest.

Table 10.3 AICDs – who needs referring for consideration of implantation of one?

* Although this indication is backed up by evidence from the MADIT II trial, the healthcare cost implications are enormous and this is neither a routine indication in the UK at present nor likely to be in the near future.

Chest pain (p. 336) and acute coronary syndromes

Initial assessment

Immediately, when she arrives:

• Risk factor profile (smoking, hypertension, lipids, diabetes, family history, age, gender, ethnic origin)

• Brief examination (BP, pulse, murmurs, chest signs)

• Relieve pain, e.g. if ischaemic ECG give diamorphine 5–10 mg IV and an anti-emetic

Causes of chest pain to consider

• Aortic dissection (see later)

• Pericarditis: sharp central pain, related to posture and respiration

• Pleurisy: sharp, usually lateral, related to respiration

• Muscular: related to posture, localised tenderness

• Herpes zoster: nerve root distribution, rash might appear later

• Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: retrosternal burning pain but can be very similar to angina.

Note: Many episodes of chest pain do not easily fit into any category and patients are often admitted and treated for acute coronary syndromes. Their symptoms should be assessed in conjunction with their risk factor profile. If in doubt, it is safer to admit.

What features would make you suspect a dissecting aneurysm?

• Pain tends to radiate to back, starts abruptly and is often intense and described as tearing.

• On examination: absent arm or leg pulses, murmur of aortic regurgitation, different BP in arms, neurological signs.

• ECG might be normal or show inferior ischaemia or MI.

• As the dissection in the aortic wall extends proximally, first it disrupts the origin of the subclavian arteries (affecting arm BP), then the carotid arteries (causing neurological sequelae), the origin of the right coronary artery – causing inferior ischaemia – and finally the aortic valve is disrupted causing aortic regurgitation.

If you clinically suspect a dissecting aneurysm you must

• Get a chest X-ray to look for mediastinal widening.

• Never give thrombolytic therapy, heparin or anti-platelet therapy.

• Carefully reduce BP with IV labetolol or sodium nitroprusside.

• Discuss with a cardiothoracic centre.

• CT with contrast or an MRI with contrast: although trans-oesophageal echo (TOE) is an excellent investigation it must be done by a very senior operator and should really be done in the cardiothoracic centre with surgeons on standby.

Immediate medical management in A&E

• IV access should be gained and bloods sent for cardiac markers, biochemistry, lipid profile, FBC and clotting profile.

• Oxygen is no longer recommended in the 2008 British Thoracic Society guidelines, unless the patient is hypoxaemic (check on pulse oximeter).

• Aspirin 300 mg chewed, then 75–150 mg daily, should be given.

• Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) 0.3–1 mg should be given for pain relief, repeated as necessary (provided BP is not compromised). This can be followed by an IV infusion of 1–10 mg/hour, which is titrated to pain whilst aiming to keep systolic BP > 100 mmHg.

• IV diamorphine 2.5–5 mg or morphine 10 mg is used as analgesia, with metoclopramide 10 mg as an antiemetic.

• IV β-blockade with metoprolol is given in 5 mg boluses (up to a total of 15 mg), provided the patient is not in cardiogenic shock and/or hypotensive, and that there are no contraindications (e.g. asthma).

• Patients with a STEMI ideally should start β-blockers on the first day, provided they are definitely haemodynamically stable. If there is any doubt, wait until they are stable, to avoid the possibility of cardiac shock developing.

• All ACS patients should be transferred to a coronary care unit (CCU) for continuous monitoring and further specialist care.

• Patients with ACS should have clopidogrel 600 mg loading dose, unless PCI is not being done, in which case the loading dose should be 300 mg; thereafter 75 mg daily is given in addition to aspirin. It has been shown to reduce mortality and the occurrence of major vascular events without an increase in the risk of bleeding in STEMI ACS. Prasugrel 60 mg is an alternative

• N.B. Proton pump inhibitors, particularly omeprazole, reduce the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel because they are inhibitors of cytochrome p450 (CYP2C19), but have only a small therapeutic effect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree