Carcinomas

Primary lung carcinomas account for the highest number of cancer deaths in the United States each year. Carcinomas are tumors of the lung epithelium, including the bronchial mucosa. The four primary histopathologic cell types of lung carcinoma are adenocarcinoma, squamous-cell carcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma (collectively referred to as non-small-cell carcinomas), and small-cell carcinoma. Subtypes of the four major cell types and other, often rare, histopathologic types of primary pulmonary carcinoma occur and are included in this chapter. Several tumors that have been categorized together in some of the classification schemes are illustrated separately here according to the distinctiveness of their histopathology to emphasize pattern recognition for the practicing pathologist. For a classification scheme of lung carcinomas, please refer to the 2004 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart.

Part 1 Adenocarcinoma

Alvaro C. Laga

Timothy C. Allen

Mary L. Ostrowski

Philip T. Cagle

Adenocarcinomas are glandular epithelial cancers and are the most common cell type of lung cancer, accounting for slightly more than 30% of all lung cancers in many series. Adenocarcinomas are frequently histologically heterogeneous. Major histologic subtypes include acinar (gland-forming), papillary, bronchioloalveolar, solid adenocarcinoma with mucin, and adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes. Most adenocarcinomas consist of two or more of the subtypes and therefore fall into the mixed subtype. It is common to see central scarring in pulmonary adenocarcinomas and a focal bronchioloalveolar-like pattern at the periphery of the tumor. Due to distinctive clinicopathologic features, bronchioloalveolar carcinomas are discussed in Part 2 of this chapter.

Cytologic Features

Tissue fragments, cell clusters, single cells.

Eccentric nuclei with finely granular chromatin.

Central macronucleoli, acinar type.

Foamy or vacuolated, usually cyanophilic, cytoplasm.

Occasional large cytoplasmic vacuoles.

Histologic Features

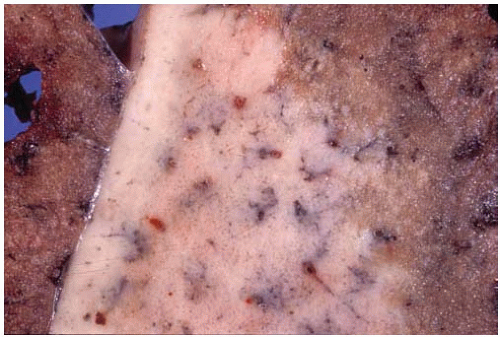

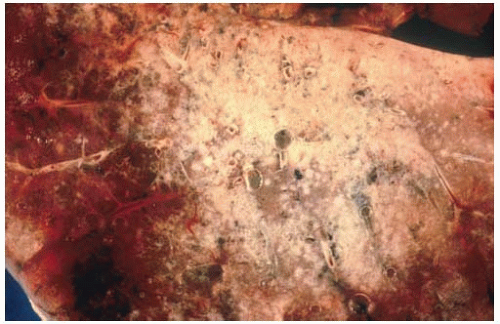

Gray-white, grossly lobulated lesions often with central scarring and anthracotic pigment.

Histopathologically, adenocarcinomas form acinar structures like glands and tubules and often produce mucin.

Microscopic subtypes include acinar, papillary, bronchioloalveolar, and solid with mucin production.

More poorly differentiated tumors tend to loose gland formation and tend toward a solid pattern.

Most adenocarcinomas are histologically heterogeneous and therefore have mixed subtypes.

Variant patterns include fetal adenocarcinoma (well-differentiated fetal adenocarcinoma), mucinous (“colloid”) adenocarcinoma, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, signet-ring adenocarcinoma, clear-cell adenocarcinoma, and sarcomatoid (sarcomatous or spindle-cell) adenocarcinoma.

True bronchioloalveolar carcinoma can currently be diagnosed only in the setting of an adenocarcinoma growing in a lepidic fashion without stromal invasion and is discussed separately.

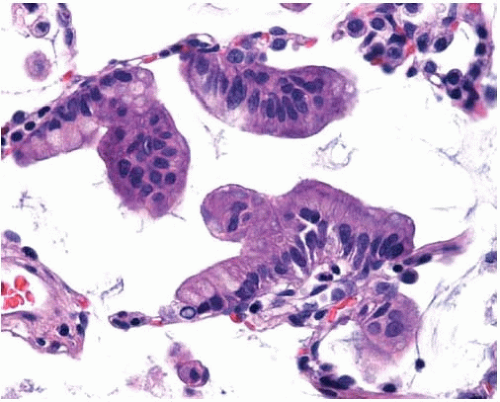

True papillary adenocarcinoma can be distinguished from bronchioloalveolar carcinoma by the following criteria: papillary morphology with complex secondary and tertiary branching in more than 75% of the tumor, stromal invasion and destruction of normal lung architecture, and marked nuclear atypia with occasional “dirty necrosis.”

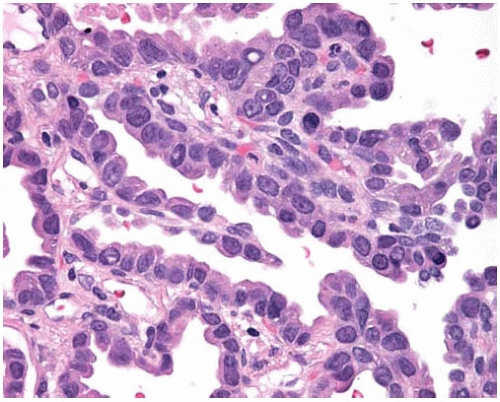

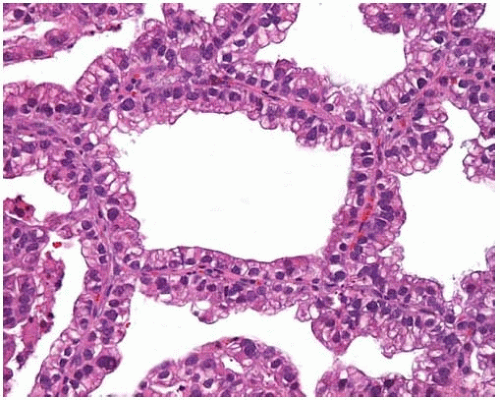

The micropapillary pattern can be distinguished from the papillary pattern by the absence of fibrovascular cores in the projections and is discussed in Subpart 1.1.

Positive immunoreactivity usually with CK7 and AE1/AE3, CEA, TTF-1, EMA, and HMFG-2; often with LeuM1 (CD-15), BerEP4, and B72.3; and occasionally with vimentin.

Negative immunoreactivity with CK5/CK6 and CK20 in the vast majority of cases.

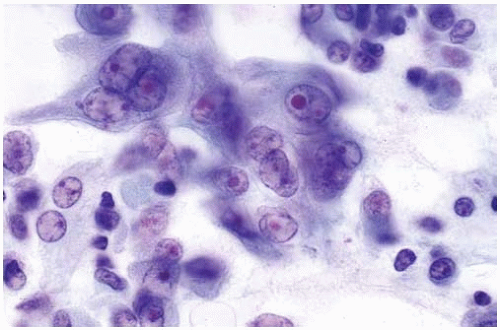

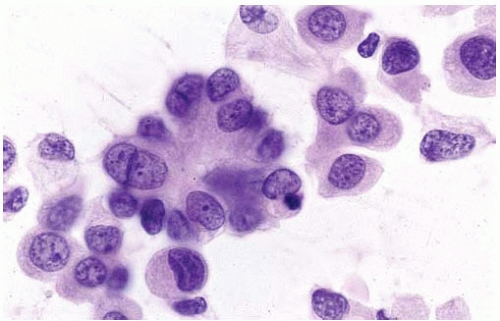

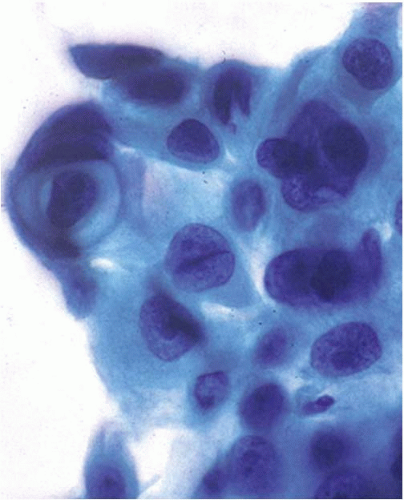

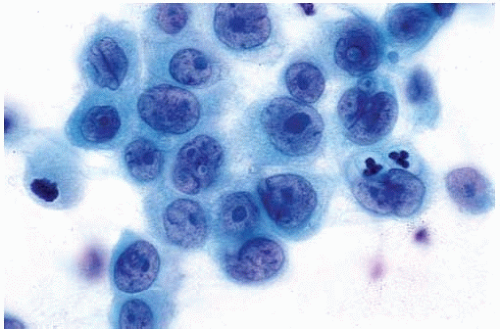

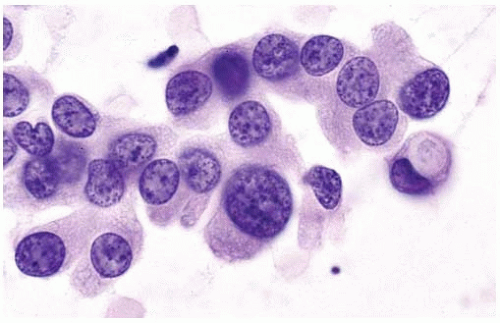

Figure 10.2 Cytology figure showing abundant cytoplasm with enlarged nuclei with finely granular chromatin. |

Figure 10.4 Cytology figure showing mucinous adenocarcinoma with large cytoplasmic vacuoles and eccentric nuclei. |

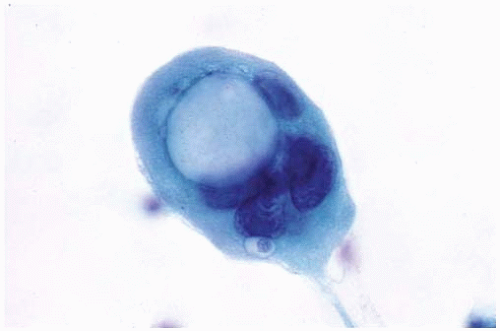

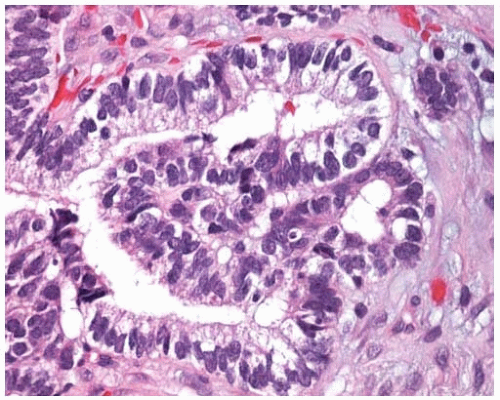

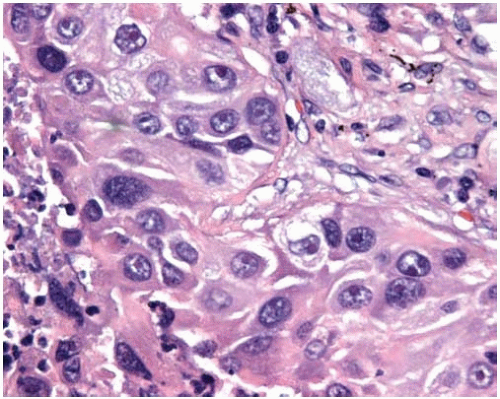

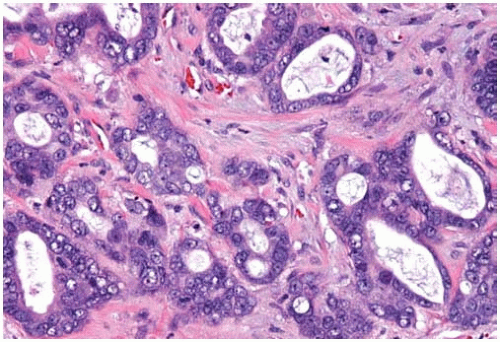

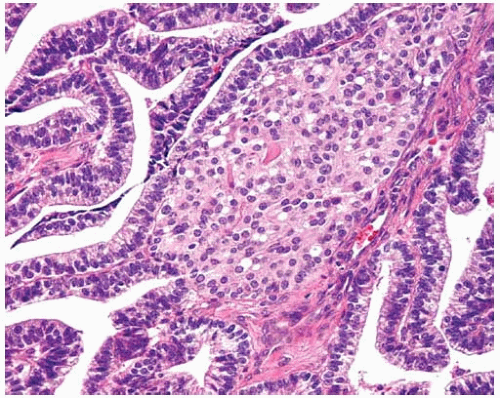

Figure 10.8 Acinar pattern of adenocarcinoma with desmoplastic stroma containing glands with malignant cells exhibiting pleomorphic nuclei. |

Figure 10.10 Irregularly shaped invasive glands of adenocarcinoma at periphery of so-called central scar. |

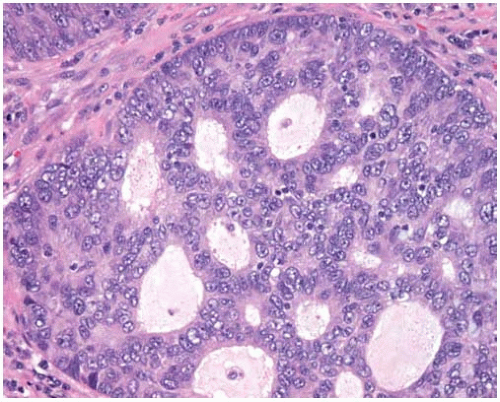

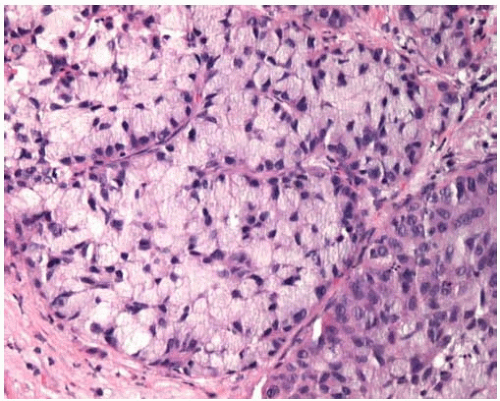

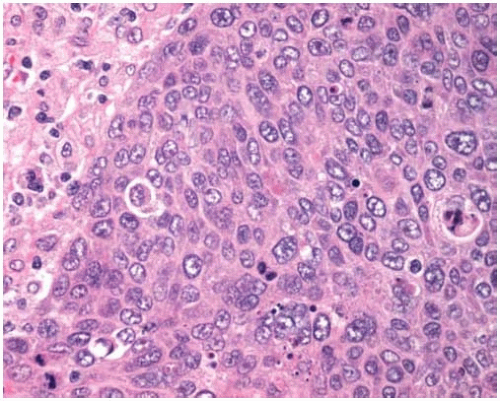

Figure 10.11 Solid pattern of adenocarcinoma with a sheet of malignant cells with abundant cytoplasm and scattered mitotic figures lacking gland formation. |

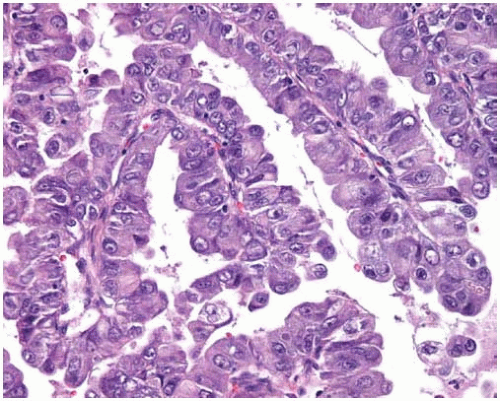

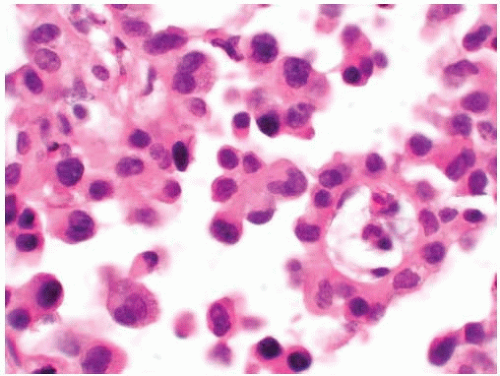

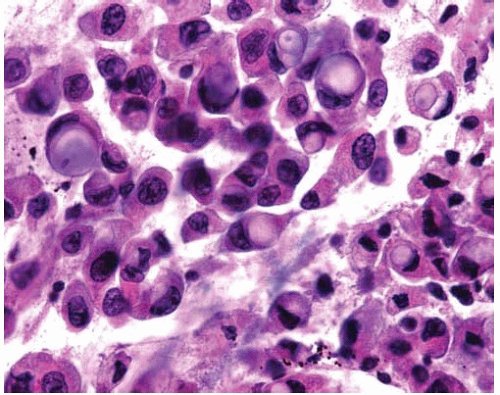

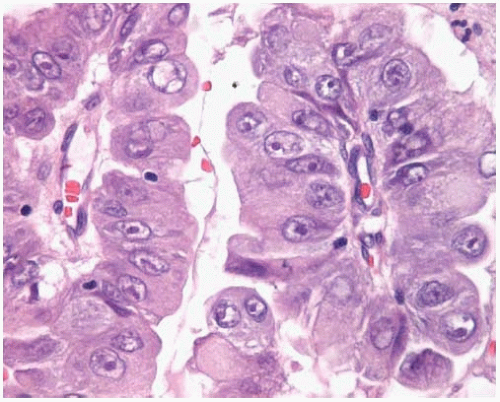

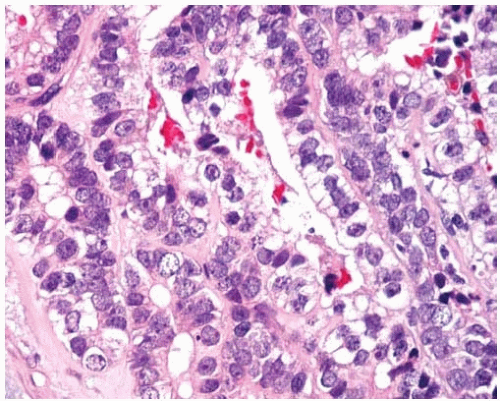

Figure 10.13 Higher power of papillary adenocarcinoma showing atypical vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. |

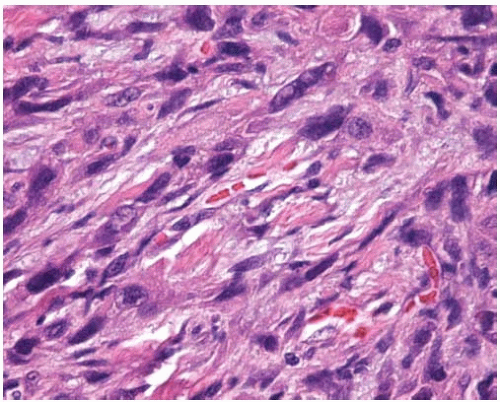

Figure 10.15 Sarcomatoid (sarcomatous) pattern of adenocarcinoma composed of spindled cells with elongated pleomorphic nuclei. |

Subpart 1.1 Adenocarcinoma with Micropapillary Component

Andras Khoor

Keith M. Kerr

Adenocarcinomas of the lung may possess a micropapillary component. This component can range from focal to prominent and may be associated with any conventional histologic subtype. Adenocarcinomas with a micropapillary component are more likely to metastasize and have a poorer prognosis.

Histologic Features

The micropapillary component displays small papillary tufts, which lack a central fibrovascular core.

Subpart 1.2 Fetal Adenocarcinoma

Timothy C. Allen

Philip T. Cagle

Fetal adenocarcinoma is an uncommon primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma that arises in both men and women generally as an asymptomatic central or peripheral solitary lung mass. It has a peak incidence in the fourth decade. The majority of fetal adenocarcinomas are well differentiated; however, a poorly differentiated or high-grade variant of fetal adenocarcinoma may rarely occur. Fetal adenocarcinoma is histologically similar to the epithelial component of pulmonary blastoma, but the tumors have distinct clinical features. The more common well-differentiated variant of fetal adenocarcinoma has a better prognosis than the more common types of adenocarcinoma, or than biphasic pulmonary blastoma.

Histologic Features

The tumor is characterized by tubules lined by glycogen-rich columnar cells that resemble the fetal lung at 10 to 15 weeks gestational age.

The tubular or glandular structures resemble endometrial glands, with prominent supranuclear and subnuclear vacuolization, and the columnar tumor cells contain glycogen-rich cytoplasm that is diastase sensitive, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive, and mucin negative.

Round-to oval-shaped morules composed of polygonal cells containing abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm are interspersed within the tumor glands.

Surrounding benign stroma contains inconspicuous spindle cells lying within myxomatous connective tissue.

Tumor cells are generally immunopositive with EMA, TTF-1, CAM5.2, CEA, AE1/EA3, GATA-6, and β-catenin; and are generally immunonegative with S-100, Estrogen receptor, Progesterone receptor, desmin, p53, chromogranin, and synaptophysin.

High-grade tumors have glandular disorganization without morules, large areas of necrosis, stromal desmoplasia, and areas of transition to more common histologic patterns of adenocarcinoma.

Tumor cells in the high-grade variant contain large, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and anisonucleosis.

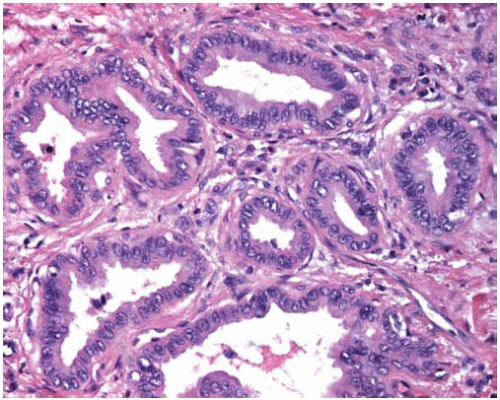

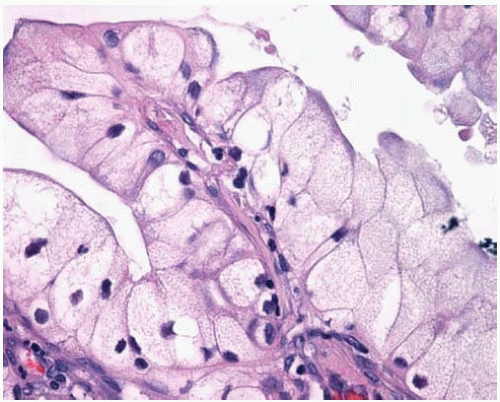

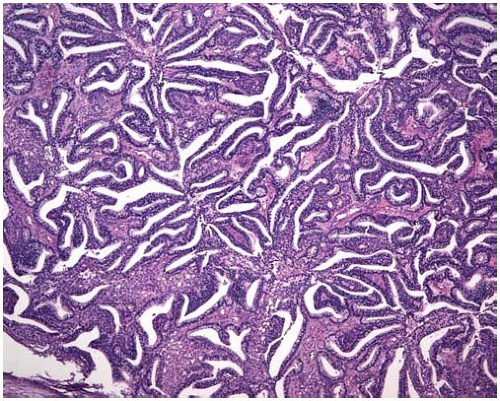

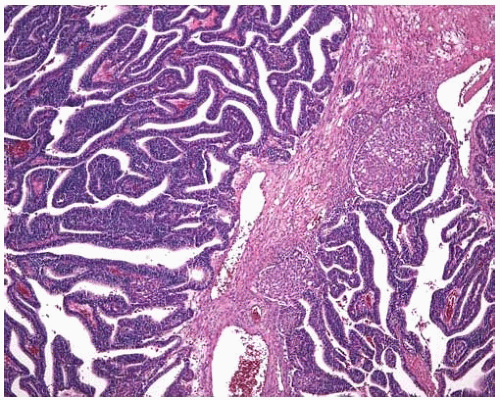

Figure 10.20 Fetal adenocarcinoma, well-differentiated or low-grade variant, appears similar to tfetal lung or endometrial glands, displaying a villiform tubular pattern. |

Figure 10.21 The glandular component of this well-differentiated fetal adenocarcinoma shows two squamoid morules. |

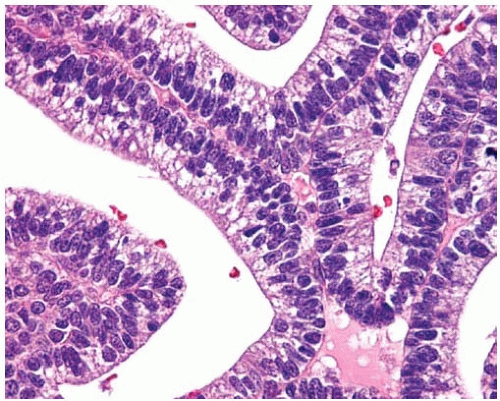

Figure 10.22 On high power, columnar cells in a well-differentiated fetal adenocarcinoma contain glycogen-rich cytoplasm and basally arranged uniform nuclei. |

Figure 10.23 This squamoid morule in a well-differentiated fetal adenocarcinoma consists of ovoid to polygonal cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. |

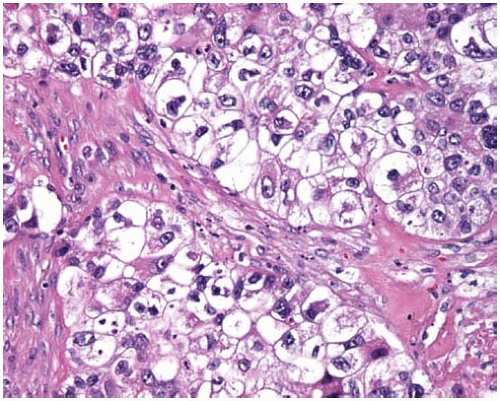

Figure 10.24 High-grade fetal adenocarcinoma shows glycogen-containing columnar cells with nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli. |

Part 2 Bronchioloalveolar Carcinomas

Alvaro C. Laga

Timothy C. Allen

Mary L. Ostrowski

Philip T. Cagle

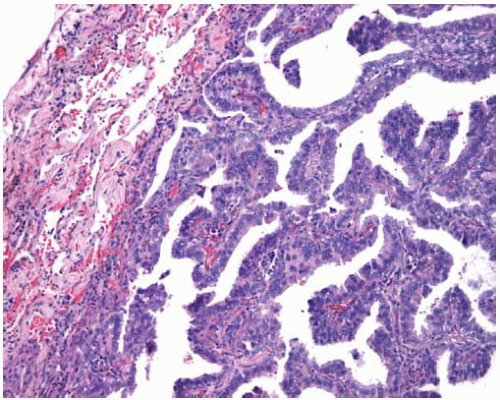

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) is defined as adenocarcinoma of the lung that grows in a lepidic fashion along intact alveolar septa without invasion. BAC can be nonmucinous, mucinous, or a mixture of these two subtypes. BAC, particularly the nonmucinous subtype, may be associated with areas of subpleural alveolar collapse, fibrosis, and pleural puckering apparently without stromal invasion, referred to in the past as a scar. Some BACs, particularly the mucinous subtype, grow in a pneumonic pattern spreading through the air spaces. BAC-like growth around the edge of an invasive adenocarcinoma is very common but is only a component of an adenocarcinoma of mixed cell types in that setting. A final diagnosis of BAC can be achieved only on a surgical resection specimen because bronchoscopic or needle biopsies are insufficient to exclude the presence of invasive growth. Metastatic adenocarcinomas to the lung may grow in a lepidic pattern on intact alveolar septa mimicking BAC, including metastatic adenocarcinomas of the colon, pancreas, and breast.

Cytologic Features

Ball-like clusters (three-dimensional), papillary fronds, florets.

Single cells.

Round to oval nuclei, bland chromatin.

Nucleoli (sometimes small).

Occasional secretory vacuoles, intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions, psammoma bodies.

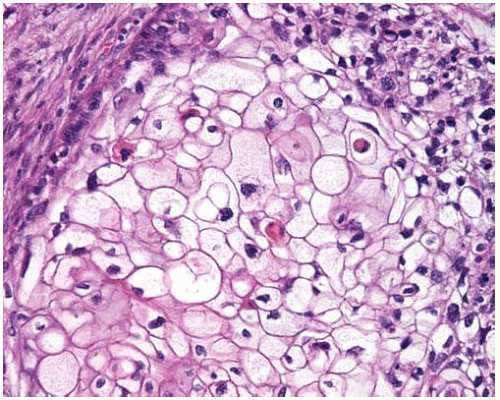

Histologic Features

Mucinous BACs tend to be multicentric and characteristically have mucin production evident by gross and microscopic examination; they can cause lobar consolidation resembling pneumonia.

Mucinous BACs consist of tall columnar cells with abundant apical cytoplasmic mucin and small basally oriented nuclei growing along intact alveolar septa; the alveolar septa are usually thin and delicate.

Mucinous BACs may form discontinuous tufts of cells on the alveolar septal surfaces, may project into the alveolar spaces as pseudopapillae, or may shed into mucin-filled alveolar spaces.

Nonmucinous BACs are more likely to be solitary tumors and may be associated with subpleural alveolar collapse, fibrosis, and pleural puckering without apparent invasion previously referred to as a scar.

Nonmucinous BACs are composed of cuboidal-to-columnar cells proliferating along intact alveolar septa; the cells may have a hobnail or sawtooth appearance and may project into the alveolar spaces as tufts or pseudopapillae; the alveolar septa may be thickened.

Nuclear inclusions may be found in the nonmucinous variant and may be PAS and surfactant apoprotein positive.

Generally, BACs are immunopositive for CEA and B72.3.

Nonmucinous BACs are typically immunopositive for TTF-1 and CK7.

Mucinous BACs are typically immunonegative for TTF-1 and may be immunopositive for CK20.

Figure 10.26 Wedge resection of nonmucinous BAC showing subpleural tumor with associated subpleural consolidation or so-called scar. |

Figure 10.28 Cytology figure showing round to oval nuclei with occasional small nucleoli and a secretory vacuole. |

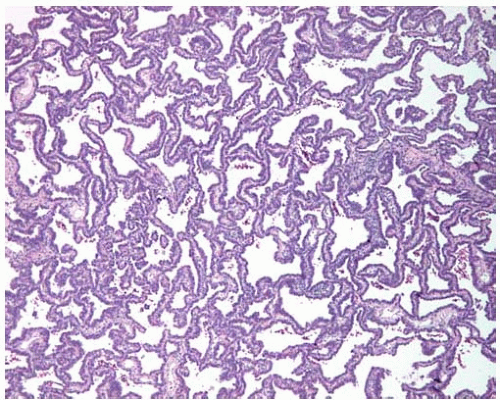

Figure 10.31 Subpleural nonmucinous BAC showing circumscription and mildly thickened alveolar septa. |

Figure 10.32 Nonmucinous BAC showing cuboidal to columnar cells with focal intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions. |

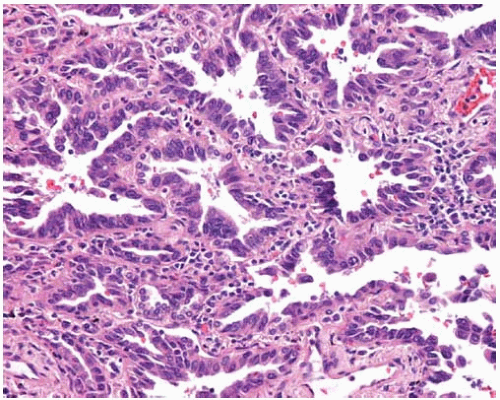

Figure 10.33 BAC with cuboidal-to-columnar cells with basally oriented nuclei and eosinophilic or vacuolated cytoplasm proliferating along intact alveolar septa. |

Figure 10.34 Mucinous BAC cells with abundant apical mucin and small basal nuclei lining thin, delicate alveolar septa and projecting into the alveolar spaces as tufts or pseudopapillae. |

Part 3 Squamous-Cell Carcinoma

Handan E. Zeren

Alvaro C. Laga

Timothy C. Allen

Carlos Bedrossian

Mary L. Ostrowski

Philip T. Cagle

Squamous-cell carcinoma is a cancer with keratinization and/or intercellular bridges. It accounts for about 30% of all lung cancers in many series. Two-thirds present as central lung tumors. Squamous-cell carcinomas of the lung may have clear-cell, small-cell, papillary, and basaloid subtypes. Papillary squamous-cell carcinomas often show a pattern of exophytic endobronchial growth and are discussed in Subpart 3.1 of this chapter. Basaloid carcinomas are discussed in Part 10.

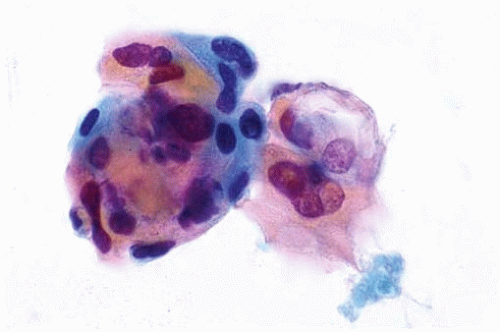

Cytologic Features

Single cells and small clusters in sputum.

Sheets of cells (“fish in a stream”), bronchial brushings, and fine-needle aspiration.

Marked cellular pleomorphism due to bizarre cytoplasmic shapes (tadpole or caudate cells, spindle or fiber cells).

Hyperchromatic, “inkblot” nuclei.

In poorly differentiated cases, nucleoli may be prominent.

Cytoplasm ranges from dense and orangeophilic to deeply cyanophilic (Papanicolaou stain) due to keratin, and may be abundant with prominent cell borders.

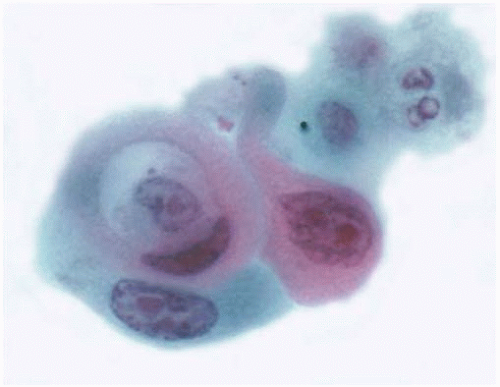

Herxheimer spirals composed of keratin in the cytoplasm, endoectoplasm, and intercellular bridges are present in well-differentiated cases.

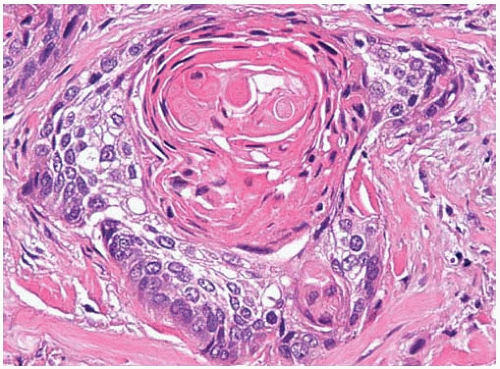

Histologic Features

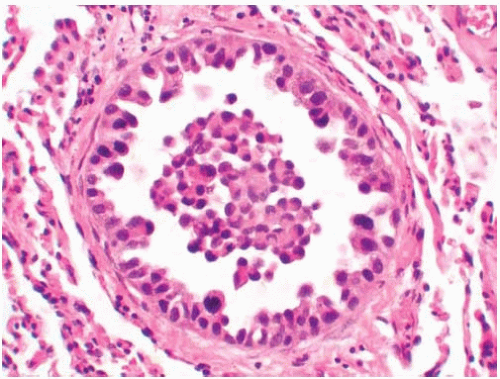

Squamous-cell carcinomas arise most often in bronchi, particularly segmental bronchi.

Squamous differentiation is identified by intercellular bridges, squamous pearl formation, and individual cell keratinization.

These features are apparent in well-differentiated tumors but are difficult or impossible to find in poorly differentiated tumors.

The small-cell variant is a poorly differentiated squamous-cell carcinoma with small tumor cells with nuclear and cytoplasmic features of squamous-cell carcinoma.

Positive immunoreactivity usually with AE1/AE3, CK5/CK6, 34BE12, EMA, and HMFG-2, often with polyclonal CEA, and occasionally with vimentin.

Negative immunoreactivity with TTF-1 in the great majority of squamous-cell carcinomas.

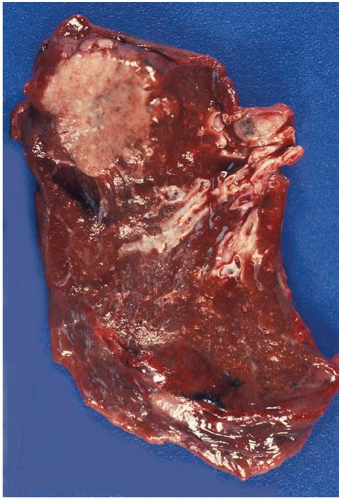

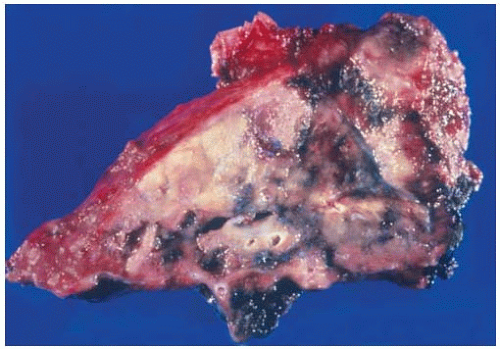

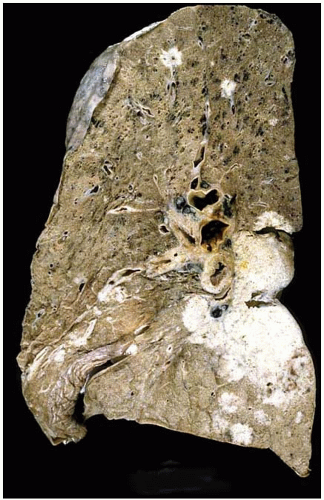

Figure 10.36 Gross figure of squamous-cell carcinoma showing a central tumor mass with bronchial and hilar lymph node involvement, and peripheral satellite lesions. |

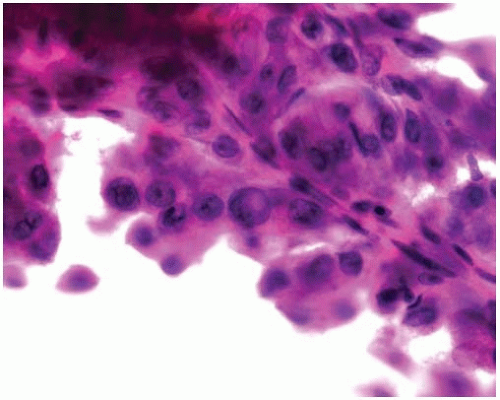

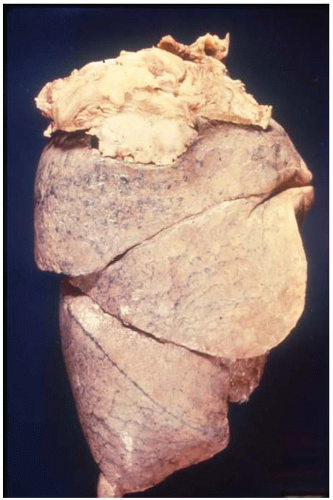

Figure 10.37 Gross figure of a squamous-cell carcinoma showing a superior sulcus tumor (Pancoast tumor) arising from the apex of the right lung. |

Figure 10.38 Cytology figure showing small clusters of squamous cells exhibiting nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromatic “inkblot” nuclei. |

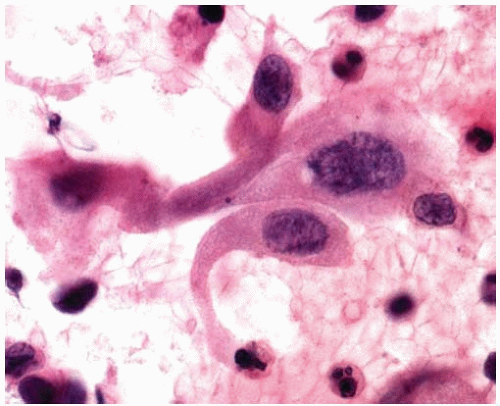

Figure 10.40 Cytology figure showing Herxheimer spiral and pleomorphic nuclei, some containing prominent nucleoli. |

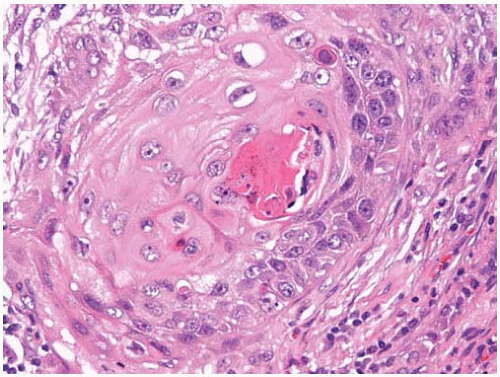

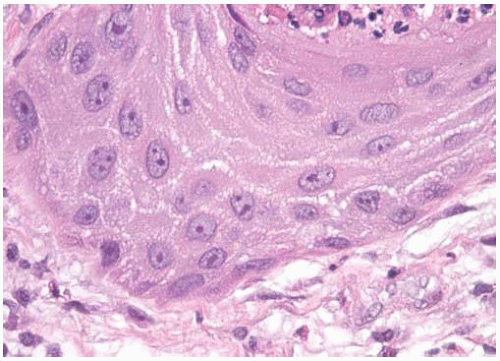

Figure 10.43 Well-differentiated squamous-cell carcinoma with prominent keratinization and keratin pearl formation. |

Figure 10.46 Clear-cell pattern of squamous-cell carcinoma showing cells with clear cytoplasm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|