12 Cancer

Concepts of cancer chemotherapy

Chemotherapy

The chemotherapeutic techniques currently used include:

A diagnosis of cancer carries a significant social and emotional impact. Hair loss and sickness are more often the initial concern for patients, rather than other potentially serious side-effects of chemotherapy. Nausea and vomiting should be taken seriously in cancer management, as these can have a devastating impact on quality of life; antiemetic drugs are discussed in Chapter 8.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Mechanisms of action

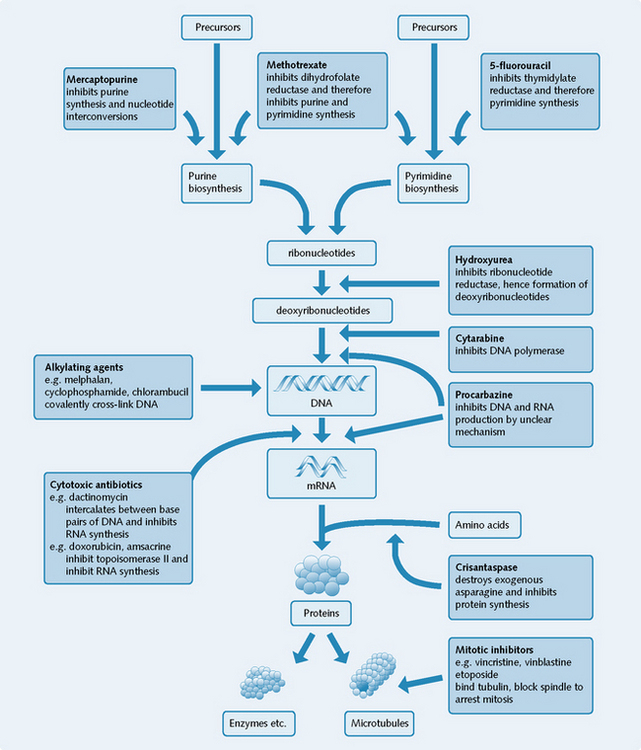

Most cytotoxic drugs affect DNA synthesis. They can be classified according to their site of action on the process of DNA synthesis within the cancer cell (Fig. 12.1). Cytotoxic drugs are therefore most active against actively cycling/proliferating cells, both normal and malignant, and least active against non-dividing cells.

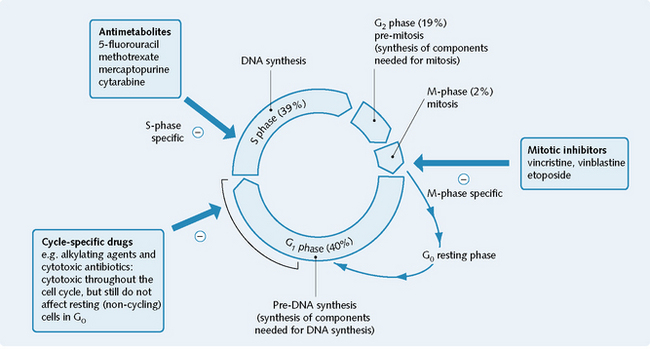

Some drugs are only effective at killing cycling cells during specific parts of the cell cycle. These are known as phase-specific drugs (Fig. 12.2). Other drugs are cytotoxic towards cycling cells throughout the cell cycle (e.g. alkylating agents) and are known as cycle-specific drugs.

Selectivity

Cytotoxic drugs affect all dividing tissues, both normal and malignant, and thus are likely to have general toxic side-effects (see Fig. 12.4). The side-effects of cytotoxic drugs are most often related to the inhibition of division of non-cancerous host cells, namely in the gut, in the bone marrow and in the reproductive and immune systems.

Relative selectivity can occur with some cancers because:

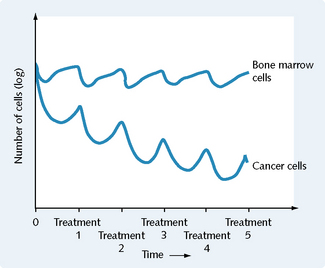

Knowledge of these principles and knowing that cytotoxic drugs kill a constant fraction, not a constant number, of cells, lays down the foundation for chemotherapeutic dosing schedules (Fig. 12.3).

Mechanisms of genetic resistance to cytotoxic drugs

The mechanisms of genetic resistance to cytotoxic drugs include:

Cytotoxic agents

Cytotoxic agents, the major group of anticancer drugs, include the:

Alkylating agents

Examples of alkylating agents include melphalan, cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree