INTRODUCTION

In a large lecture hall of fellow clinicians-to-be, I was told that my job as a physician is not to be concerned with costs but rather to treat patients. My wrist, moving frantically left to right on my page taking notes, stopped. I looked up and my mind wandered: What an odd message to tell those who will be listening to ill people’s symptoms, prescribing medicine, ordering tests, and orchestrating people’s care to not worry about costs.

We have set up this dichotomy of treating the patient or being concerned with costs. We have soaked medicine with the belief that cost-conscious care is rationing at the bedside and the public is fed fear messages that clinicians who care about costs are limiting their care. How can we teach future clinicians to be so out-of-touch with one of the greatest concerns that many patients have when seeing a clinician? We know that people forgo medications because of high prices, medical bankruptcy plagues many, and that some cannot seek care due to cost. What other industries allow someone so crucially involved in controlling costs immunity from worrying about them? Does medicine’s unique role of saving lives exempt it from keeping an eye on the register? Is good care not cost-conscious care?

Clinicians do not have the luxury to not care about costs.

—adapted from Sarah Jorgenson, Costs of Care, 2013

As Sarah Jorgenson eloquently highlights, teaching medical students how to consider costs while caring for patients is uncommon—in fact, clinicians are often taught to specifically ignore costs. But times are changing, and recently, there have been increasing calls for medical education to train cost-conscious physicians.1 Educating physicians to be “cost aware” is now becoming a critical responsibility of medical schools and residency programs. The Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has included cost awareness and stewardship into its systems-based practice competency; residents are asked “to incorporate considerations of cost awareness and risk-benefit analysis in patient and/or population-based care as appropriate.”2 To raise the visibility of this need, the American College of Physicians (ACP) has proposed that high-value, cost-conscious care be added as a standalone “7th core competency” of residency education.3

MEDICAL EDUCATION AND VALUE-BASED CARE

Although current efforts to integrate value-based care into medical training may appear new, it may be surprising to learn that such efforts actually date back to as early as 1975! In that year, Harvard Professor of Medicine Dr Howard Hiatt famously encouraged physicians collaborate with other experts and the public to protect the medical commons (see Chapter 5).4 In 1984, UCSF Professor of Medicine Dr Stephen Schroeder and colleagues rigorously evaluated an educational intervention, which included a weekly lecture as well as audit and feedback, designed to reduce lab and radiology use at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF). Unfortunately, there was no significant effect on total hospital charges.5 One reason such prior efforts have not resulted in widespread change could be in part due to the local nature of the efforts, in addition to the myriad of cultural, operational, and systemic challenges such innovations have faced, including the need to align stakeholder interests and integrate novel material into already crowded curricula.

But now, cost-containment has become an urgent national priority that is increasingly spilling over into clinical education. For example, policymakers and accrediting organizations have all expressed concern that residency training does not produce cost-effective physicians. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which advises Medicare on payment issues, has identified cost-consciousness as a critical deficiency in current residency training.6 In fact, a MedPAC RAND Study in 2009 demonstrated that only 23% of 26 internal medicine residency programs reported their residents get training in cost-effectiveness.7 A 2012 survey from the Association of Program Directors of Internal Medicine (APDIM) continues to highlight the lack of formal curricula in this area, finding that only 15% of programs had curricula related to cost, although an additional 50% of programs were thinking about starting one.8 Furthermore, while the majority (85%) of program directors thought that graduate medical education has the responsibility to curtail the rising costs of care, just under half (47%) felt that their faculty working with residents model cost-conscious patient care.

The situation is no better in our nation’s medical schools. Data from the 2013 Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Graduation Medical Student Questionnaire demonstrate that 63% of graduating students feel the training they received on healthcare economics was “inadequate.”9 Of all the topical areas assessed, training in healthcare economics was judged to be the worst. Given the lack of curricula at both the undergraduate and graduate level, it is worth considering what obstacles exist. In both the RAND and APDIM studies, a lack of qualified faculty to teach and role model cost-conscious care was cited as a major barrier. Furthermore, the culture of medical training environments creates what educators often refer to as the “hidden curriculum” (as discussed below). It is not just that we are not taught much about healthcare costs, but the way that we’re taught may be actively training us to be bad stewards of healthcare resources.

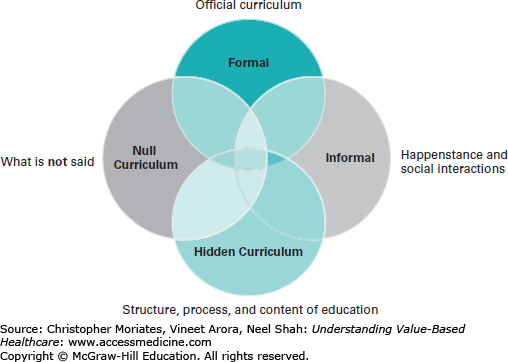

To address value-based education, it is important that we first understand how medical education is actually delivered in teaching hospitals. As Mayo Clinic Professor Fred Hafferty has recognized, there are several types of “curricula” that pass down knowledge and attitudes to medical trainees (Figure 11-1).10 The most obvious and familiar to the casual observer is the “formal curriculum,” which refers to the actual planned lessons or written curricular objectives and content that are delivered to medical trainees. When asked about curricula, this is often the component that is discussed. But, a powerful and surreptitious undercurrent is also at work in medical education, aptly named the “hidden curriculum.” The hidden curriculum describes lessons that are not taught formally, but are learned through the transmission of norms, values, and beliefs conveyed in the classroom and the social environment. Medical education experts believe the hidden curriculum to be more powerful than the formal curriculum for instilling values, beliefs, and behaviors. Lastly, the “null curriculum” emphasizes that topics or issues that are not taught are deemed to not be important, thus often sending an unintended message to trainees.

To see how the hidden curriculum plays a major role in promoting a culture of overuse and waste, consider how medical trainees are often rewarded for suggesting rare diagnoses in the differential diagnoses for patients, and that many resident conferences, such as traditional morning reports, emphasize bizarre and very rare cases that require more intensive workups rather than focusing on the most likely diagnosis for the patient’s chief complaint.11 Residents are also more often criticized for sins of omission than for commission. For example, a resident is more likely to be asked why he or she did not order a certain test than to be questioned about why he or she did order a test. Moreover, questioning whether a test is needed, opens up a trainee to possible criticism for “not being thorough.”12

In fact, there are many reasons that trainees may overorder tests and it is easy to see how these relate to the hidden and null curricula (Table 11-1).13 Actively tackling these reasons for overuse in the training environment clearly map to several of the ACGME core competencies, most notably, systems-based practice, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal communication, and professionalism (see Table 11-1). Let us think about preemptive ordering. Systems inefficiencies in hospitals lead to an often-used workaround: to jump the gun and “preemptively” order a test just in case you might need it later, realizing that a delay in ordering could ultimately result in a postponed discharge.14 As a result, many patients receive tests they do not necessarily need, which lead to both direct and indirect effects on patient safety. Unnecessary testing can lead to patient harm, as discussed throughout this book. In addition, if, say, an MRI was labeled as “urgent” when it is in fact not, a less sick patient may take priority in getting a scan over a patient who truly needed it.

Top 10 reasons doctors overorder tests

| Top 10 | Problem | Solution | ACGME Competency | ABIM Charter Commitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How we are taught | It’s taboo for doctors to consider cost | Change culture | Systems-based practice | Improving access to care |

| Create framework for considering costs as part of patient care paradigm | Just distribution of resources | |||

| Trying our best | We’re worried … and risk averse | Teach diagnostic strategies | Professionalism | Improving quality of care |

| Practice-based learning and improvement | Improving access to care | |||

| Preemptive ordering | Ordering everything now is easier and saves time | Semiannual review of order-entry by workflow task force, composed of all members of care team | Systems-based practice | Just distribution of resources |

| Covering all bases | Doing more is equated with being thorough | Build cost-effectiveness data into workflow | Practice-based learning and improvement | Improving quality of care |

| General unawareness | We do not know how much things cost | Monthly “Costs of Care” morning report | Systems-based practice | Improving access to care |

| Just distribution of resources | ||||

| Broader ignorance | Costs are opaque | Build price-point examples into workflow | Systems-based practice | Improving access to care |

| Just distribution of resources | ||||

| Unaware of setting’s effect on cost | Pricing is not intuitive | Institution-specific cheat sheets for commonly ordered tests | Systems-based practice | Improving access to care |

| Just distribution of resources | ||||

| Defensive medicine | Malpractice claims are real … and exaggerated | Teaching module designed to differentiate standards of care versus evidence-based medicine | Systems-based practice | Patient welfare |

| Practice-based learning and improvement | Improving access to care | |||

| Patient requests | The customer is always right | Communication module aimed at understanding and addressing requests | Professionalism | Honesty with patients |

| Patient care | Maintaining appropriate relations with patients | |||

| Interpersonal and communication skills | ||||

| Lack of oversight | Discomfort with third party oversight, among doctors and patients | Evidence-based demonstrations of better outcomes and lower costs through oversight | Systems-based practice | Professional responsibilities |

Another reason physicians may overorder a test is that patients directly request the test (see Chapter 10).15 While clinicians are often taught to be patient-centered and serve their patients, information asymmetry leads patients to make medical decisions that may not always be the most rational, or in their actual best interest. This is why the competency of interpersonal communication is so important (see also Chapter 12). In fact, studies have shown that through better communication, physicians are able to counsel patients to avoid unnecessary tests. In one study published in 1987, patients were randomized to receive immediate x-rays or a brief educational intervention for back pain.16 After 3 weeks, fewer patients in the education group believed “everyone with back pain should have an x-ray” (44% education vs 73% x-ray). Patient outcomes were no different in both groups, and no serious diagnoses were missed.

Story From the Frontlines: On Being 100% Sure

As busy practitioners, we may forget that our trainees do not always have the skills to make cost judgments prior to ordering tests, especially when a test is just a computer-click away. As teachers, though, it is imperative we reinforce the fact that tests have costs and should only be used as adjuncts to our clinical assessments. The toughest thing to teach is what not to order.

Unfortunately, medical economics is not routinely taught in medical school and we either never learn it at all or we learn it informally from our mentors, if we are lucky. The emergency room is an area where we always seem to struggle with trying not to “miss a disaster.” A chief resident came to me to discuss a woman who presented with left lower quadrant pain that was suspicious for ovarian torsion, a surgical emergency. If you suspect it, you operate. She underwent a pelvic ultrasound that was completely normal, and by the time the evaluation was completed, her pain had resolved. Discharge; end of story, right? No. The resident, still concerned, wanted to observe her in the Emergency Room for four more hours and repeat the ultrasound to “double-check.”

“Why would you do that? What risk factors does she have for torsion?” I asked.

The resident responded, “None, but I want to be sure.”

“If you’re that worried, then we should go to the OR, not wait for another ultrasound,” I advised.

“I’m not concerned enough for the OR, but don’t we need to be 100% sure?” she asked.

“We can never be 100% sure 100% of the time, but if we use good judgment, we can be pretty darn close. The remaining uncertainty, you have to learn to deal with. She’ll call again if the pain returns,” I said.

It didn’t.

In a time when there’s constant worry about potential lawsuits, it’s very difficult to embrace the concept of tolerating uncertainty. We are so used to being explorers trying to find the proverbial zebra, that it becomes harder to see the horse when it’s staring us in the face. That’s how these million-dollar workups occur when sometimes a tincture of time is the best treatment. I was fortunate to have teachers who helped instill the importance of clinical examination, who engaged me in understanding medical costs, but I am not perfect by any means. It is a continual learning process, which should be a formal part of medical training. Until then, all I can do is take baby steps, starting with myself and those I educate. Hopefully, many people taking many baby steps can work to reduce costs and provide better care, which, in the end, is our ultimate goal.

—Padma Kandadai. “On Being 100% Sure.”

Costs of Care, 2010. (www.costsofcare.org)

MOVING TOWARD COMPETENCIES FOR TEACHING VALUE-BASED CARE

Recently, the ACGME has launched a new institutional approach to accreditation based on the Clinical Learning Environment Review, or “CLER,” with a focus on integrating residents into the hospital quality and safety mission, including value. For example, under the pathway of education on quality improvement, the ACGME states “the focus will be on the extent to which residents/fellows receive experiential learning in quality improvement that includes consideration of underuse, overuse, and misuses in the diagnosis or treatment of patients.”17 Early experiences with CLER site visits demonstrate that residents are seldom engaged in systems-based practice and even when they are, their efforts to improve quality and safety may not be well-integrated with the approach of their institution.18

In the summer of 2014, these gaps in physician skills for delivering high-value care prompted the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to issue a report that proposes radical changes in the structure and financing of graduate medical education.19 In particular, the IOM committee recommended creating a new “GME Transformation Fund” to support efforts that help close the value-based care training gap. Based on lessons from the Transformation Fund pilot projects, they proposed tying how much an academic medical center gets paid to performance. In a New England Journal of Medicine article that summarizes their recommendations, committee chairs Gail Wilensky and Donald Berwick point out, “GME can and should be better leveraged than it has been to date for … meeting the needs of the American people.”20

In 2013, The ABIM Foundation convened a meeting of stakeholders around promoting high-value care education for trainees. At that meeting, the following competencies, designed to be interdisciplinary, were proposed for trainees (Table 11-2).

Competencies proposed for Choosing Wisely

| Competency | Skills |

|---|---|

| Know why to Choose Wisely |

|

| Know when to Choose Wisely |

|

| Know How to Choose Wisely |

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree