Chapter Forty-Two. Breech presentation

Introduction

Any presentation of the fetus other than a vertex is called a malpresentation, which includes breech, face, brow and shoulder. These presentations have in common an ill-fitting presenting part which may be associated with early rupture of the membranes. There is also the likelihood of poor uterine action, leading to prolongation of labour. Each malpresentation leads to a different mechanism for descent and there may be difficulties in delivery; an understanding of the movements made by the fetus in response to the maternal pelvis will help to prevent injury to the woman or her baby. The risk of morbidity and mortality for the fetus is increased and malpresentations may result in operative delivery. Breech presentation is discussed in this chapter and the other malpresentations in Chapter 43.

Breech presentation

Breech presentation is where the lie is longitudinal but the fetal buttocks lie in the lower segment of the uterus. This presentation is found in 3–4% of all deliveries at term (RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) (2006a) and RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) (2006b)). One in four fetuses will present by the breech at some stage in pregnancy but as pregnancy progresses spontaneous version to a vertex presentation is likely to occur, especially in multigravidae. In many cases there is no known cause; however, certain factors contribute to breech presentation such as extended legs, multiple pregnancy, preterm labour, polyhydramnios, hydrocephaly, uterine abnormality and placenta praevia (Coates 2003).

Types of breech presentation

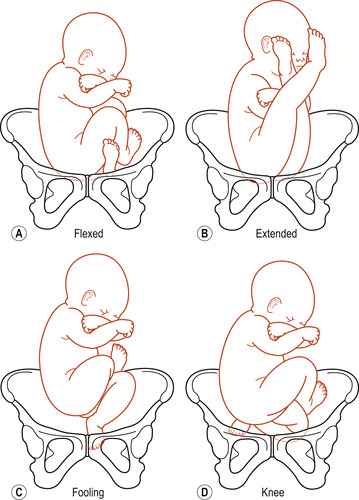

Depending on the relationship of the lower limb(s) to the fetal trunk, four types of breech presentation can be described (Fig. 42.1). This can influence the diagnosis of breech presentation antenatally and the complications likely to occur at delivery:

1. Complete or flexed breech (Fig. 42.1A): the thighs and knees are flexed and the feet are close to the buttocks (tailor sitting or squatting), which occurs in 10–15% and is most common in multigravidae.

2. Extended or frank breech (Fig. 42.1B): the fetal thighs are flexed and the legs extended at the knees. The legs lie alongside the trunk with the feet near the head. This is the most common of the four types of breech presentation, occurring in 45–50%, and is seen most commonly in primigravidae near to term. The firm uterine and abdominal muscles prevent fetal movement so that the fetus is unable to flex its knees and there is limited likelihood of a turn to cephalic presentation.

3. Footling presentation (Fig. 42.1C): one or both hips and knees are extended and the feet present below the buttocks. This rare complication is more common in preterm labour.

4. Knee presentation (Fig. 42.1D): one or both hips are extended and the knees flexed. The knee(s) present below the buttocks. This is the rarest of the four presentations.

|

| Figure 42.1 Types of breech presentations. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

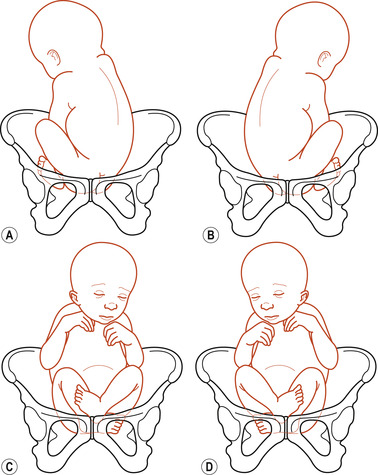

As in vertex presentations, the baby presenting by the breech can take up different positions (Fig. 42.2).

|

| Figure 42.2 Breech positions. (A) Left sacroanterior. (B) Right sacroanterior. (C) Right sacroposterior. (D) Left sacroposterior. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Aetiology

Many of the causes of persistent breech presentation are associated with conditions which either restrict the movement of the fetus or allow excessive movement of the fetus. Others involve the health of the fetus (see Table 42.1).

| Restricted space | Excessive intrauterine space | Fetal causes |

|---|---|---|

| Primigravidae with firm uterine and abdominal muscles | Grande multiparity because of lax uterine and abdominal muscles | Fetal abnormalities |

| Uterine malformations such as bicornuate uterus | Polyhydramnios | Fetal death in utero |

| Uterine fibroids | Decreased fetal activity | |

| Contracted pelvis preventing engagement of the presenting part | Impaired fetal growth | |

| Multiple pregnancy | Short umbilical cord | |

| Placenta praevia | ||

| Oligohydramnios |

Diagnosis of breech presentation

On discussion

A past history of a previous breech presentation could suggest a uterine anomaly and an increased risk of repeated breech. If the woman complains of discomfort under the ribs it may be due to the presence in the fundus of the hard fetal head. The woman may also be aware of fetal kicking movements below the umbilicus.

On abdominal examination

Findings are:

BOX 42.1

BOX 42.1

• Inspection: usually reveals nothing unusual.

• Palpation: the presenting part feels firm but not hard or smooth. The head may be felt in the fundus, hard, round and ballottable. Box 42.1 presents possible findings on abdominal palpation of breech presentation.

BOX 42.1

BOX 42.1 ABDOMINAL PALPATION OF BREECH

Although abdominal examination is the main diagnostic tool it may be difficult to recognise in the primigravid woman with an extended breech. The breech may be deep in the pelvis and simulate an engaged head. The feet lie alongside the head and both prevent identification by palpation and prevent movement of the head on the neck elicited by ballottement. Finally, if the breech is engaged, the fetal heart may be heard in the expected position for a vertex presentation.

• Auscultation: fetal heart sounds may be heard above the umbilicus.

On vaginal examination

On vaginal examination, either small parts or the breech itself may be detected. It is essential to distinguish between a hand and a foot if small parts are felt (a hand might grasp the examiner’s finger, whereas a foot will not!). The breech itself is smooth and rounded and may feel like a vertex. A vaginal examination will also exclude a deeply engaged head either in pregnancy or labour. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate the shoulders, which lie at the level of the pelvic brim, from the breech.

Ultrasound scan

Diagnosis in a suspected breech presentation can be made by ultrasound. The fetus should be examined for anomalies at the same time.

Associated risk factors

The increased risk of morbidity and mortality in breech deliveries may be four times that of cephalic presentation but is partly dependent on associated factors. These factors include prematurity, congenital abnormalities, placenta praevia and placental abruption (Enkin et al 2000). Prolapse of the umbilical cord may lead to anoxia and fetal death, as may entrapment of the fetal head behind an incompletely dilated cervix. The woman is also placed at risk because of the possible delivery by caesarean section (CS).

Congenital abnormality

The presence of a congenital abnormality occurs more frequently with a breech presentation than with a vertex. The risk of congenital abnormality may be as high as 15% in babies of less than 1500 g (Arias 1993). The most common major abnormality is a defect of the neural tube such as meningomyelocele, hydrocephaly or anencephaly. Anomalies of the internal systems such as the gastrointestinal, respiratory, cardiovascular and urinary systems are also found. Congenital dislocation of the hip is the most common problem, occurring in three times as many girls as boys.

Risks at delivery

The fetus is at risk from the following:

• Intrauterine and extrauterine asphyxia, because of the delay in delivery of the head after the birth of the thorax and arms. Placental separation may occur before the birth is complete and cord compression is inevitable. Hypoxia may stimulate breathing with the inhalation of blood, liquor and mucus.

• Intracranial haemorrhage, which used to be thought to be due to rapid compression and decompression of the brain as the head descended through the pelvis, resulting in a torn tentorium cerebelli. However, it is now thought that the main cause of cerebral haemorrhage is anoxia and congestion of the cerebral vessels.

• Skeletal fractures and dislocations, damage to muscles and nerves and rupture of abdominal organs due to difficulties arising during delivery or to faulty delivery technique.

• Genital oedema and bruising, because of the formation of a caput succedaneum.

Management of pregnancy

Any woman found to have a breech presentation after 32 weeks should be seen by an obstetrician. With her full involvement, a decision needs to be made about the safest option for delivery. NICE (2004) state that in an uncomplicated singleton breech pregnancy at 36 weeks’ gestation, women should be offered external cephalic version (ECV). However, women excluded would be labouring women, women with ruptured membranes, vaginal bleeding, uterine scar or abnormality, medical conditions and fetal compromise. If ECV is contraindicated or has been unsuccessful to reduce perinatal mortality and morbidity then women with a singleton breech presentation at term should be offered CS (NICE 2004).

Cephalic version

Promotion of spontaneous cephalic version

Various exercises and positions have been tried in an attempt to turn a breech. Hofmeyr & Kulier (2000) systematically reviewed the postural techniques ‘used by doctors, midwives and birth attendants to promote cephalic version’. The review cited the following five studies involving 392 women:

•Chenia & Crowther (1987), who modified Elkin’s procedure asking women to adopt the posture three times a day for 7 days with a full bladder.

•Bung et al (1987), who used a different technique—the ‘Indian’ version—where women are encouraged to lie down once or twice a day in a supine head-down position with the pelvis supported on a wedge-shaped cushion.

•Hartadottir & Thornton (1992), who carried out a randomised controlled trial with women with a diagnosed breech presentation after 34 weeks. One group were taught how to take up the knee–chest position for 15 min twice a day. The results were compared to a control group of normally managed women.

•Obwegeser et al (1999), who asked women to adopt the supine position with the pelvis elevated by a 30–35 cm high cushion for periods of 10 min twice a day.

•Smith et al (1999), who asked women to assume the knee–chest position for 15 min, three times a day for 1 week.

There is insufficient evidence from well-controlled trials to support the use of postural management for breech presentation and larger trials are needed to assess the clinical value of these techniques. However, these exercises do not do any harm and there are no contraindications.

Moxibustion

Moxibustion (burning herbs to stimulate acupuncture points) is a traditional Chinese method used to help version of a fetus in breech presentation (Coyle et al 2005, Lewis 2004). In this technique a practitioner inserts heated acupuncture needles, then places small cones of moxa on the needle heads and ignites them. The acupuncture point Bladder 67 (BL67) is located at the tip of the fifth toe; its Chinese name is Zhiyin (Coyle et al 2005). It is a way of applying heat locally to regulate, tone and supplement the body’s flow of Qi (vital energy). This method is popular in China and Japan.

The systematic review of Coyle et al (2005) evaluated the evidence from three trials; their aim was ‘to examine the effectiveness and safety of moxibustion on changing the presentation of an unborn baby in the breech position, the need for ECV, mode of birth, and perinatal morbidity and mortality for breech presentation’. Meta-analysis was unable to be conducted due to the difference in interventions and overall small sample size (579 women in total). Only one trial reported on other outcome measures relevant to the review and stated that moxibustion reduced the need for ECV and resulted in decreased use of oxytocin before or during labour for women who had vaginal deliveries. However, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of moxibustion to correct a breech presentation. Moxibustion may be beneficial in reducing the need for ECV and decreasing the use of oxytocin; however, further well-designed randomised controlled trials to evaluate moxibustion for breech presentation which report on clinically relevant outcomes as well as the safety of the intervention are required.

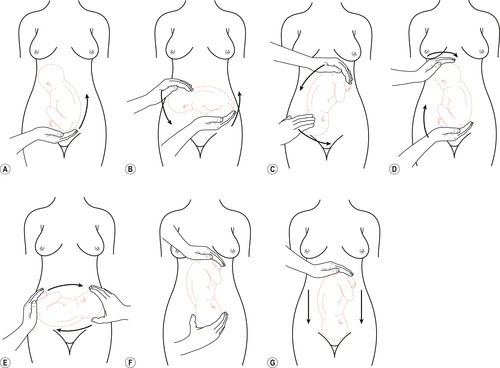

External cephalic version

During ECV the fetus is manipulated through the abdominal wall to turn it from a breech to a cephalic presentation (RCOG 2006a) (Fig. 42.3). This manual manoeuvre has always been controversial, especially if carried out before 36 weeks. There are risks attached to the procedure: bleeding from the placental site, cord entanglement, causing fetal distress, converting the lie and presentation to an undeliverable one and initiating preterm labour. To reduce these risks to a minimum, the following contraindications are described:

• History of infertility.

• Elderly primigravida.

• Hypertension.

• Rhesus-negative mother.

• Cephalopelvic disproportion.

• Uterine scar.

• Placenta praevia or placental abruption.

• Multiple pregnancy.

• Congenital malformations.

• Intrauterine fetal death.

|

| Figure 42.3 External cephalic version. (A) Palpation and mobilisation of the breech. (B) Manual forward rotation using both hands, one to push the breech and the other to guide the vertex. (C) Completion of forward roll. (D) Backward flip using both hands. (E) Quarter turn accomplished. Continue to push breech upwards and vertex downwards. (F) Completion of external version. (G) Gently push the breech downwards to direct vertex into pelvis. (Reproduced with permission from Clay et al 1993.) |

The role of ECV in three different situations has been systematically reviewed:

1. External cephalic version before term (Hutton & Hofmeyr 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree