I. INTRODUCTION. This chapter provides a systematic approach to breast pathology, which enables pathologists to effectively play their role in today’s interdisciplinary care of patients with breast disease, especially cancer. It is not intended to be a compendium of histologic alterations occurring in the breast, which is enormous and covered in many excellent textbooks on the subject (see Suggested Readings). Instead, it is based on a template addressing the most common alterations, in order of clinical importance, ranging from potentially lethal cancers to common benign changes (e-Appendix 18.1)* Diagnoses are conveyed in a concise, standardized manner addressing specific issues important to other specialists–such as correlating histologic with mammographic findings for radiologists, status of surgical margins for surgeons, tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging [essential elements of which include: tumor size (T), nodal status (N), and distant metastasis (M)] for oncologists, and so on. Although templates cannot be all inclusive, and must be updated to stay current, their advantages far outweigh their limitations.

This chapter begins with a discussion of the methods used in grossing breast specimens. A discussion of normal breast follows, because a comprehensive understanding of normal is necessary to appreciate what is abnormal. This is followed by discussions of invasive carcinomas, noninvasive carcinomas, prognostic and predictive biomarkers, common benign lesions, and reporting results.

II. SPECIMEN PROCESSING

A. General approach. The primary goals of grossing in breast pathology are to (i) identify the specimen, determine its orientation, and dimensions; (ii) identify the presence, location, and dimensions of lesions (masses, calcifications, etc.); (iii) estimate the distance of lesions from surgical margins; and (iv) take small samples for more precise microscopic evaluation. Secondary goals include taking samples from various other locations depending on the type of specimen (e.g., nipple, all quadrants, and lymph nodes associated with mastectomies).

There are many methods of grossing breast surgical specimens; all acceptable methods adequately address the goals listed above even if their specific strategies vary. This section provides a basic grossing strategy to manage most surgical breast specimens, followed by more detailed discussion of the most common types of samples. More detailed information on grossing can be

found in specialized texts (Manual of Surgical Pathology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingston; 2006).

The central element of the basic strategy is a generic grossing template (e-Appendix 18.2), which can accommodate specimens of almost any size, ranging from small lumpectomies to large mastectomies. Utilization of the template creates a permanent record (diagram) of the most important features of a specimen (e.g., size, orientation, location of samples, location of mass lesions, and distance of lesions from margins); the small amount of extra time required to create the diagram has several additional benefits, including (i) providing relatively precise information on the size and distribution of lesions that are not apparent grossly; (ii) enabling better control of margins; (iii) assistance in taking additional samples if necessary; and (iv) facilitating succinct, comprehensive, and standardized gross dictations.

The main steps of grossing a surgical breast specimen are as follows:

1. Identification

2. Orientation

3. Dimensions

4. Inking of margins

5. Sectioning into thin slices to facilitate fixation. Small specimens are usually cut (from 2 to 4 mm in thickness) into a few slices and entirely submitted in a corresponding number of cassettes for formalin fixation. Larger specimens are usually cut into slices (5 mm thick and hinged at the bottom to maintain intact orientation), and allowed to fix before submitting samples in cassettes.

6. Fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for a minimum of 8 to 12 hours. The recommended maximum fixation time is 72 hours.

7. Production of a diagram of the specimen on the template. Diagrams are more informative and useful than gross dictations alone.

B. Ancillary information. Most patients with breast pathology present with a clinically or radiologically detected mass and/or a mammographically detected abnormality, most often in the form of microcalcification. The manner of presentation often dictates the approach to specimen processing. Because most breast specimens lack natural anatomical landmarks, careful specimen processing–especially margin assessment–is crucial for accurate pathologic interpretation. In addition, evaluation of specimen radiographs represents an integral part of examination of breast specimens, and should be reviewed whenever available. Review provides valuable information as to the nature of the lesion (ill-defined vs. well-defined mass; microcalcification); location of the lesion(s); and assists planning of the sectioning of the specimen.

C. Specimen types. Most breast specimens received for pathologic evaluation are in one of the following forms.

1. Needle core biopsies have almost totally replaced fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy specimens for the initial pathologic evaluation of localized breast lesions in most centers. They are obtained to diagnose palpable breast masses or nonpalpable breast lesions detected by screening mammography, such as stellate densities or suspicious microcalcifications. For nonpalpable lesions, biopsy is usually obtained using image guidance (ultrasound guided, stereotactic, or MRI guided). Vacuum-assisted biopsies increase the volume of tissue obtained for microscopic examination. If biopsy is performed for calcifications, a radiograph of the specimen is often obtained to confirm that the calcifications have been adequately sampled. After describing the shape, size, and color of the tissue cores, they should be aligned in parallel and placed in the cassette between two sponges (preferable) or wrapped in tissue paper; similar to biopsies from other organs, overstuffing of cassettes should be avoided. Formalin fixation time is absolutely critical,

as underfixation and overfixation both may result in altered biomarker results by immunohistochemistry. Current College of American Pathologists/American Society of Clinical Oncology (CAP/ASCO) guidelines recommend that core needle biopsy samples be fixed in formalin for 6 to 48 hours prior to processing. At least three histologic levels should be obtained from each paraffin block to ensure adequate representation of the lesion(s). For all other breast specimens, the histologic findings should always be correlated with the clinical and radiologic findings, and, if discrepant (such as when microcalcifications are not seen in original sections of a biopsy performed for microcalcifications) additional deeper sections from the block, and/or radiographic images of the paraffin block need to be examined to resolve the discrepancy.

2. Excisional biopsy/lumpectomy specimens are either oriented or nonoriented. Nonoriented specimens are those in which evaluation of the status of specific margins is not required by the surgeon (such as excisions of benign lesions or malignant lesions with separate margin specimens); nonetheless, these specimens should be inked. Oriented specimens need to be inked differentially to facilitate specific margin orientation. A four-ink color approach is useful to orient the margins (the superior, inferior, anterior, and posterior margins will be inked by four different colors); the medial and lateral margins are amputated, sliced, and completely submitted in separate cassettes. Another acceptable approach is to use six ink colors to orient all the margins.

For these specimens, the gross dimensions and weight should be recorded. Then, the specimen should be serially sectioned as soon as possible to allow for adequate penetration of fixative. Such sectioning is usually performed perpendicular to the long axis of the specimen; however, sectioning may be influenced by the shape and proximity of the lesion(s) to particular margins. Gauze should be placed between the sections, and the specimen should be fixed in formalin for 6 to 48 hours before submitting samples in cassettes.

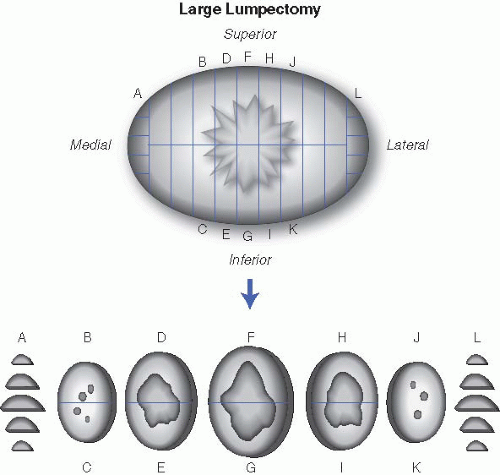

a. If excision is performed for mass lesions. The size of the mass (accurate to nearest millimeter), consistency (gelatinous, rubbery, firm, or hard), growth pattern (well circumscribed, infiltrative, pushing), and distance from margins should all be described. The presence and size of a biopsy cavity should also be noted. For well-circumscribed lesions thought to be benign (such as fibroadenomas), one section per centimeter of the lesion is usually sufficient. Ill-defined and suspicious lesions need to be entirely submitted if possible. If the mass is too large to be completely submitted, at least one section per centimeter of the mass should be submitted. Margins are microscopically examined by submitting a perpendicular section of the mass with each margin (superior, inferior, anterior, posterior). If the margins are distant from the mass, representative-shave sections suffice. Medial and lateral margins are usually amputated, sliced, and completely submitted in labeled cassettes (Fig. 18.1). Representative sections of grossly noninvolved breast should additionally be submitted with particular attention to fibrous areas of the breast.

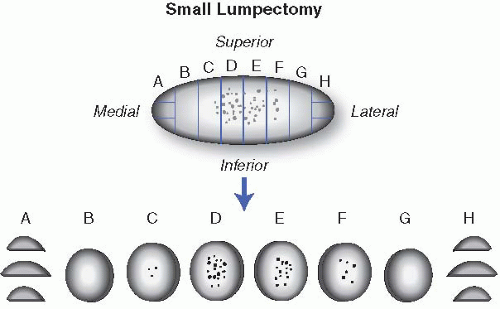

b. If excision is performed for imaging-detected microcalcifications. Most of these specimens show no significant gross pathology. These specimens are usually oriented (by two perpendicular sutures or clips), contain a guiding wire, and are accompanied by a specimen radiograph. Similarly, a surgical clip may have been placed at the area of previous core biopsy. The guiding wire, which is placed at the site of imaging-detected abnormality, should be used in conjunction with the specimen radiograph to preferentially sample areas of abnormality, immediately adjacent areas, as well as the margins. For smaller specimens, it is preferable to entirely

submit the specimen in consecutive sections, as this facilitates accurate estimation of the extent of disease. In larger specimens, wide sampling of the area of the wire tip and adjacent tissue is advised. If possible, the specimen should be sectioned in a way that facilitates some inference of the three-dimensional aspects of the lesion when histologic sections are evaluated. This can be achieved by labeling the cassette numbers on a generic diagram that can be used to determine the relationship of tissue blocks containing abnormalities with each other (see e-Appendix 18.2). If there are multiple lesions, their location and relationship to each other should be documented; in addition to sampling each lesion individually, sections from normal-appearing areas in between the lesions can be used to determine whether they are individual or multiple masses. Representative sections from grossly noninvolved breast with attention to fibrous areas should also be submitted (Fig. 18.2). In situations where gross examination and initial set of sections do not show a histologic abnormality, the entire specimen, or at least all the fibrous parts of the specimen, should be submitted for microscopic examination.

3. Margin and biopsy reexcisions. These cases range from unorientated flat portions of tissue that should be laid flat in a cassette (shave margin), where the presence of any malignancy seen histologically would thus be indicative of a positive margin; to larger, variably oriented specimens that should be inked preferentially, bread-loafed perpendicular to the new margin (oriented), and submitted in a manner to examine the new margin. For reexcisions following invasive carcinoma, the status of gross residual disease should be evaluated as well as its relationship to different excision margins; in the absence of gross disease, the specimen need only to be representatively sampled. For reexcisions following a diagnosis of in situ carcinoma, the specimen may need to be more widely sampled to detect residual disease and/or associated invasive carcinoma. Complete reexcision of the cavity created by a prior lumpectomy may also be performed; these specimens should be inked with respect to orientation, and serially sectioned as in a lumpectomy. The blood-filled biopsy cavity should be entirely submitted, in particular with respect to new margins to evaluate the residual disease and status of surgical margins.

4. Mastectomy specimens range from simple skin-sparing mastectomy (which removes the breast only covered by the nipple-areola complex and a narrow rim of surrounding skin), to simple mastectomy (mastectomy without axillary tissue), to modified radical mastectomy (mastectomy with axillary lymph nodes). Radical mastectomy (modified radical mastectomy with pectoral muscles), is rarely performed in current practice. Mastectomies may be prophylactic or therapeutic. When the specimen is received for pathologic examination, it should first be measured and weighed. Then, the specimen should be oriented and the surgical margins inked; it should then be serially sectioned perpendicular to the skin at 5 mm intervals from the posterior aspect, packed with gauze, and fixed in formalin overnight. The size of any

masses, including their growth pattern, location, and distance from all surgical margins, should be recorded; the same principles discussed above (for excisional biopsy/lumpectomy specimens also apply to grossing mastectomy specimens. Masses should be entirely submitted if small, in a manner that demonstrates the relationship to the surgical margin. If a mass is predominantly composed of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with focal microinvasion, submitting the entire mass is required to exclude a larger size of invasive carcinoma. In addition, at least one section of nipple, grossly normal tissue from each of the four quadrants of the breast, skin, and dermal scars from previous biopsies should be submitted for microscopic examination. If the specimen is a modified-radical mastectomy, the axillary tail should be removed and dissected for lymph nodes, which should all be submitted for microscopic evaluation (see below). A search for lymph nodes should always be performed even in simple mastectomies and if lymph nodes are found, they should be sampled accordingly. It is important to correlate the gross and microscopic findings with imaging studies to optimize patient care; for nonpalpable lesions, radiographing the specimen with submission of the entire area of radiologic abnormality is recommended.

5. Mammary implants should be documented, photographed, and inspected grossly for any evidence of leakage. One or two sections are usually sufficient to evaluate the surrounding fibrous “capsule” that is usually submitted with the implant(s).

6. Sentinel lymph nodes. The sentinel lymph node(s) is (are) the first lymph node or group of lymph nodes that drain the breast into the axilla and in most cases they are the first lymph node(s) involved in metastatic carcinoma. Only rarely does cancer “skip” the sentinel node and metastasize to a nonsentinel lymph node. As such, specimens designated as sentinel lymph nodes should be dissected carefully. Intraoperative evaluation (frozen sections and/or touch preparations) is usually limited to lymph nodes grossly suspicious for malignancy; in these situations, intraoperative imprint cytology of the lymph node can provide results at the time of surgery. For permanent sections, each node is serially cut at 2 mm intervals and, in the absence of gross evidence of metastatic carcinoma, entirely submitted for histologic examination. There are many different protocols for microscopic evaluation of sentinel lymph node, but one common approach involves examination of three hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections from each paraffin block. The use of cytokeratin-stained sections–if initial H&E sections are negative–is optimal, but not required. In the event of a positive sentinel lymph node, axillary dissection is indicated.

7. Nonsentinel (axillary) lymph nodes. Axillary lymph node dissection may be performed in conjunction with lumpectomy in a patient with a positive sentinel lymph node, or may be performed as part of a modified radical mastectomy (see above). After carefully dissecting grossly benign appearing nodes from the fat, nodes <0.4 cm can be submitted intact, whereas larger nodes need to be bisected or trisected and submitted in a manner that permits accurate enumeration (either by submitting them in individual cassettes or by differential inking). If possible, the size of the largest grossly positive node or metastatic deposit should be measured, and the presence of extranodal extension sampled in one section. It is recommended that a minimum of 10 lymph nodes should be identified in an axillary dissection (although this number is dependent on the surgical technique and the extent of axillary lymph node dissection during surgery). Attention should also be directed to identification of possible intramammary lymph nodes, which are usually identified in the upper outer quadrant of the breast.

D. Examples of reporting template. To demonstrate the organization of a pathology report on breast samples using the discussed diagnostic template (see e-Appendix 18.1), a few examples are shown in e-Appendix 18.3.

III. NORMAL BREAST. An understanding of normal breast histology is essential for accurate histologic evaluation of breast specimens. It should be noted that what constitutes normal varies based on gender, age, menstrual phase, pregnancy, lactation, and menopausal status.

The breast represents a modified skin adnexal structure composed of major lactiferous ducts that originate from the nipple, progressively branching, until eventually inducing grape-like clusters of secretory glands as lobules. Breast development starts during the fifth week of gestation, at which time thickenings of ectoderm appear on the ventral surface of the fetus extending from axilla to the groin (mammary ridges or milk lines). The majority of this thickening regresses as the fetus develops, except an area in the pectoral region. Failure of this regression results in ectopic mammary tissue or accessory nipple. The most common location for accessory nipple is axilla.

The adult female breast consists of a series of branching ducts, ductules, and lobulated acinar units embedded within a fibroadipose stroma. Terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs) are composed of lobules, which are groups of alveolar glands, embedded in loose intralobular connective tissue that connect to a single terminal ductule. These are the structural and functional units of the breast and most pathologic processes arise within them (e-Figs. 18.1 and 18.2). The lining throughout the duct/lobular system of the breast is composed of two distinct layers: an inner (luminal) epithelial layer with a cuboidal to columnar appearance, and an outer (basal) myoepithelial layer (e-Fig. 18.3). The myoepithelial cells have variable morphologies ranging from flattened, to epithelioid with clear cytoplasm, to a myoid appearance. Identification of these two cell layers is very important in the assessment of breast lesions as they are almost always preserved in benign lesions, as well as in noninvasive malignant lesions, but are absent in invasive carcinomas. Immunohistochemistry can also be used to identify myoepithelial cells, as myoepithelial cells are usually positive for calponin, p63, CD10, and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, among other markers (e-Fig. 18.4). A panel-based approach of two or more markers is recommended (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:422). In addition, a proportion of luminal epithelial cells almost always expresses estrogen and/or progesterone receptors. The intralobular stroma is usually sharply demarcated from a denser, collagenized, paucicellular interlobular stroma. The proportion of dense stroma to adipose tissue is variable, with younger women having denser connective tissue (which partially explains why mammography is less sensitive in younger individuals). Breast lobules can be classified on the basis of their morphology into three major types. Type 1 lobules are the most primitive and rudimentary, and are usually seen in prepubertal and nulliparous women. Type 3 lobules are the most developed, and are usually seen in parous and premenopausal women. The progression from type 1 to type 3 is accompanied by additional branching and increased number of alveolar buds. Type 1 lobules also predominate in postmenopausal women and premenopausal women with breast cancer (Dev Biol. 1989;25:643; Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1994;3:219; Breast J. 2001;7:278).

After birth and in the premenstrual period, breast development starts with puberty and cyclic secretions of estrogen and progesterone. The ducts elongate and branch primarily due to estrogen stimulus and lobulocentric growth advances primarily under the influence of progesterone. In addition, the breast undergoes various physiologic changes during menstruation, pregnancy, and lactation. It is prudent to be aware of these physiologic changes since they can be mistaken for pathologic processes by an inexperienced observer. Cyclic menstrual changes in

the breast tissue are subtle in comparison with other sites such as endometrium. The follicular phase of the menstrual cycle is characterized by simple acini and collagenized stroma, while the luteal phase is characterized by apical snouting of the epithelial cells, prominent vacuolization of myoepithelial cells, and loose edematous stroma. The epithelial cells show peak mitotic activity in the late luteal phase. During pregnancy, there is progressive epithelial cell proliferation resulting in an increase in both the number and the size of TDLUs. By late pregnancy, lobular myoepithelial cells become inconspicuous while the cytoplasm of the luminal epithelium becomes vacuolated as secretions accumulate in the expanded lobules. After parturition, florid changes including the frequent presence of luminal cells with atypical nuclei protruding into the lumen (hobnail cells) can be seen, which can be alarming to the inexperienced observer (e-Fig. 18.5). Gradually and slowly, the lobules involute to their resting appearance.

In postmenopausal women, the lobules undergo involution and atrophy characterized by reduction in size and complexity with an increase in fat (type 1 lobules) (e-Figs. 18.6 to 18.8).

In contrast to women, due to lack of hormonal stimulation, TDLUs do not develop to a significant extent in men, and male breast consists of branching ducts within a fibroadipose stroma.

IV. INVASIVE BREAST CARCINOMA. Establishing the diagnosis of invasive breast cancer (IBC) is the first and most critical responsibility of pathologists (Table 18.1). Most invasive carcinomas present as a palpable mass and/or as a mammographic abnormality. However, in some cases the primary tumor is occult, and the patient may present with lymph node or distant metastasis. The purpose of the pathology report is to communicate all the diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive findings to a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, oncologists, and other specialists; some findings are strong prognostic factors (histologic type, histologic grade, lymph node status), some determine the likelihood of response to specific treatment (hormonal therapy, Trastuzumab), and some determine the need for additional surgical procedures (margin status). Determination of pathologic stage (Table 18.2) is vital to determine prognosis and to guide the therapy. In addition to pathologic stage, the prognosis of breast carcinoma is greatly dependent on additional prognostic and predictive factors that are mandatory and should be evaluated and reported for all breast carcinomas (15), and are most significant in lymph node–negative breast carcinoma.

A. Prognostic and predictive factors

1. Histologic subtype. Histologic typing remains the gold standard for classification of breast carcinoma and provides useful prognostic information. Five major types of IBC are currently recognized. Four are characterized by relatively unique/uniform histologic features and, thus, they are referred to as “special” histologic types. Collectively, the special types account for about 25% of all the IBCs, and include the so-called invasive lobular, tubular, mucinous, and medullary carcinomas (approximately 15%, 5%, 2% to 3%, and 1% to 2%, respectively) (Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:S4). The remaining ˜75% of the breast carcinomas are histologically and prognostically very heterogeneous and are referred to as invasive ductal carcinomas (IDCs), no special type, or, not otherwise specified. Except, perhaps, invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), all the special type carcinomas have more favorable prognosis compared with IDC, although the degree of improved outcome is variable for different types. In addition, some pathologists recognize other less common special types of invasive carcinoma that have a favorable prognosis. These include invasive cribriform (1%), papillary (<1%), and adenoid cystic (0.1%) carcinomas. Different experts have used variable criteria for diagnosing special type carcinomas, which is partially responsible for the variable prevalence reported in different studies. For practical purposes, a carcinoma is considered “special type” if >90% of the tumor shows special type differentiation. For a carcinoma to be considered “no special type,” >50% of the tumor should lack special type differentiation. Tumors with special type differentiation in 50% to 90% of the tumor are considered variants or mixed types. Some experts believe that variant/mixed type carcinomas have an outcome intermediate between no special type carcinomas and the pure special type carcinomas (Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:334; Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:S4). The diagnostic features of major histologic subtypes of breast carcinoma are summarized in Table 18.3 and are discussed in more detail below.

TABLE 18.1 World Health Organization Classification of Breast Tumors

Epithelial tumors

Myoepithelial lesions

Invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified

Myoepitheliosis

Invasive lobular carcinoma

Adenomyoepithelial adenosis

Tubular carcinoma

Adenomyoepithelioma

Invasive cribriform carcinoma

Malignant myoepithelioma

Medullary carcinoma

Mucinous carcinoma and related tumors

Mesenchymal tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors

Hemangioma

Invasive papillary carcinoma

Angiomatosis

Invasive micropapillary carcinoma

Hemangiopericytoma

Apocrine carcinoma

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia

Metaplastic carcinomas

Myofibroblastoma

Lipid-rich carcinoma

Fibromatosis (aggressive)

Secretory carcinoma

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

Oncocytic carcinoma

Lipoma and angiolipoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Granular cell tumor

Acinic cell carcinoma

Neurofibroma

Glycogen-rich clear cell carcinoma

Schwannoma

Sebaceous carcinoma

Angiosarcoma

Inflammatory carcinoma

Liposarcoma

Lobular neoplasia

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Lobular carcinoma in situ

Osteosarcoma

Intraductal proliferative lesions

Leiomyoma

Usual ductal hyperplasia

Leiomyosarcoma

Flat epithelial atypia

Atypical ductal hyperplasia

Fibroepithelial tumors

DCIS

Fibroadenoma

Microinvasive carcinoma

Phyllodes tumor

Intraductal papillary neoplasms

Periductal stromal sarcoma, low grade

Papilloma

Mammary hamartoma

Atypical papilloma

Intraductal/intracystic papillary carcinoma

Tumors of the nipple

Adenomas

Nipple adenoma

Tubular adenoma

Syringomatous adenoma

Lactating adenoma

Paget’s disease of the nipple

Apocrine adenoma

Pleomorphic adenoma

Malignant lymphoma

Ductal adenoma

Metastatic tumors

Condensed from: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. Used with permission

TABLE 18.2 Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) Staging Scheme for Breast Carcinoma

Primary tumor(T)

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tis

Carcinoma in situ

Tis (DCIS)

Ductal carcinoma in situ

Tis (LCIS)

Lobular carcinoma in situ

Tis (Paget)

Paget’s disease of the nipple not associated with invasive or in situ carcinoma

T1

Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension

T1mic

Microinvasion ≤0.1 cm in greatest dimension

T1a

Tumor >0.1 cm but ≤0.5 cm in greatest dimension

T1b

Tumor >0.5 cm but ≤1 cm in greatest dimension

T1c

Tumor >1 cm but ≤2 cm in greatest dimension

T2

Tumor >2 cm but ≤5 cm in greatest dimension

T3

Tumor >5 cm in greatest dimension

T4

Tumor of any size with direct extension to chest wall and/or skin, only as described below

T4a

Extension to chest wall, not including only pectoralis muscle

T4b

Edema (including peau d’orange) or ulceration of the skin of the breast, or satellite skin nodules confined to the same breast that does not meet the criteria for inflammatory carcinoma

T4c

Both T4a and T4b

T4d

Inflammatory carcinoma

Regional lymph nodes (pN)a

pNX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

pN0

No regional lymph node metastasis or lymph node metastasis <0.2 mm. pN0 can be further classified as

pN0(i+): ITCs (<0.2 mm, or <200 nonconfluent cells on one single histologic section) detected by H&E or immunohistochemistry

pN0(mol+): Tumor cells detected only by positive molecular findings (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction)

pN1

Metastasis in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes, and/or in internal mammary nodes with microscopic disease detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically apparent (not detected clinically or by noninvasive imaging techniques)

pN1mi

Micrometastasis (>0.2 mm and <2.0 mm)

pN1a

Metastasis in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes (at least one metastasis >2.0 mm)

pN1b

Metastasis in internal mammary nodes (micro or macrometastasis)

pN1c

Metastasis in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically apparent. If associated with >3 positive axillary lymph nodes, the internal mammary nodes are classified as pN3b to reflect increased tumor burden

pN2

Metastasis in 4-9 axillary lymph nodes or in clinically apparent internal mammary lymph nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastasis

pN2a

Metastasis in 4-9 axillary lymph nodes (at least one deposit >2 mm)

pN2b

Metastasis in clinically apparent internal mammary lymph nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastasis

pN3

Metastasis in ≥10 axillary lymph nodes, or in infraclavicular lymph nodes, or in clinically apparent ipsilateral internal mammary lymph nodes in the presence of ≥1 positive axillary lymph nodes; or in >3 axillary lymph nodes with clinically negative microscopic metastasis in internal mammary lymph nodes; or in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes

pN3a

Metastasis in ≥10 axillary lymph nodes (at least one deposit >2 mm), or metastasis to the infraclavicular lymph nodes

pN3b

Metastasis in clinically apparent ipsilateral internal mammary lymph nodes in the presence of ≥1 positive axillary lymph nodes; or in >3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes with microscopic disease detected by sentinel lymph node dissection but not clinically apparent

pN3c

Metastasis in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes

Distant metastasis (M)

MX

Distant metastasis cannot be assessed

M0

No distant metastasis

M0 (i+)

Deposits of molecularly or microscopically detected tumor cells in circulating blood, bone marrow, or other nonregional nodal tissue ≤0.2 mm in a patient with no clinical or radiologic evidence of distant metastasisb

M1

Distant metastasis, determined by clinical and radiologic means, or histologically proven >0.2 mm

AJCC stage groupings

Stage 0

Tis

N0

M0

Stage IA

T1

N0

M0

Stage IB

T0

N1mi

M0

T1

N1mi

M0

Stage IIA

T0

N1c

M0

T1

N1c

M0

T2

N0

M0

Stage IIB

T2

N1

M0

T3

N0

M0

Stage IIIA

T0

N2

M0

T1

N2

M0

T2

N2

M0

T3

N1

M0

T3

N2

M0

Stage IIIB

T4

N0

M0

T4

N1

M0

T4

N2

M0

Stage IIIC

Any T

N3

M0

Stage IV

Any T

Any N

M1

a Sentinel nodes (when they are <5 in number) are indicated by adding (sn) to the designation.

b This category does not change stage grouping.

c T0 and T1 tumors with micrometastases only are classified as Stage IB.

From: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. Used with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Breast Pathology

Breast Pathology

Souzan Sanati

Omar Hameed

Joshua I. Warrick

Craig Allred