BENIGN BREAST DISORDERS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Painful, often multiple, usually bilateral masses in the breast

Rapid fluctuation in the size of the masses is common

Frequently, pain occurs or worsens and size increases during premenstrual phase of cycle

Most common age is 30-50 years. Rare in postmenopausal women not receiving hormonal replacement

Fibrocystic condition is the most frequent lesion of the breast. Although commonly referred to as “fibrocystic disease,” it does not, in fact, represent a pathologic or anatomic disorder. It is common in women 30-50 years of age but rare in postmenopausal women who are not taking hormonal replacement. Estrogen is considered a causative factor. There may be an increased risk in women who drink alcohol, especially women between 18 and 22 years of age. Fibrocystic condition encompasses a wide variety of benign histologic changes in the breast epithelium, some of which are found so commonly in normal breasts that they are probably variants of normal but have nonetheless been termed a “condition” or “disease.”

The microscopic findings of fibrocystic condition include cysts (gross and microscopic), papillomatosis, adenosis, fibrosis, and ductal epithelial hyperplasia. Although fibrocystic condition has generally been considered to increase the risk of subsequent breast cancer, only the variants with a component of epithelial proliferation (especially with atypia) or increased breast density on mammogram represent true risk factors.

Fibrocystic condition may produce an asymptomatic mass in the breast that is discovered by accident, but pain or tenderness often calls attention to it. Discomfort often occurs or worsens during the premenstrual phase of the cycle, at which time the cysts tend to enlarge. Fluctuations in size and rapid appearance or disappearance of a breast mass are common with this condition as are multiple or bilateral masses and serous nipple discharge. Patients will give a history of a transient lump in the breast or cyclic breast pain.

Mammography and ultrasonography should be used to evaluate a mass in a patient with fibrocystic condition. Ultrasonography alone may be used in women under 30 years of age. Because a mass due to fibrocystic condition is difficult to distinguish from carcinoma on the basis of clinical findings, suspicious lesions should be biopsied. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology may be used, but if a suspicious mass that is nonmalignant on cytologic examination does not resolve over several months, it should be excised or biopsied by core needle. Surgery should be conservative, since the primary objective is to exclude cancer. Occasionally, FNA cytology will suffice. Simple mastectomy or extensive removal of breast tissue is rarely, if ever, indicated for fibrocystic condition.

Pain, fluctuation in size, and multiplicity of lesions are the features most helpful in differentiating fibrocystic condition from carcinoma. If a dominant mass is present, the diagnosis of cancer should be assumed until disproven by biopsy. Mammography may be helpful, but the breast tissue in these young women is usually too radiodense to permit a worthwhile study. Sonography is useful in differentiating a cystic mass from a solid mass, especially in women with dense breasts. Final diagnosis, however, depends on analysis of the excisional biopsy specimen or needle biopsy.

When the diagnosis of fibrocystic condition has been established by previous biopsy or is likely because the history is classic, aspiration of a discrete mass suggestive of a cyst is indicated to alleviate pain and, more importantly, to confirm the cystic nature of the mass. The patient is reexamined at intervals thereafter. If no fluid is obtained by aspiration, if fluid is bloody, if a mass persists after aspiration, or if at any time during follow-up a persistent or recurrent mass is noted, biopsy should be performed.

Breast pain associated with generalized fibrocystic condition is best treated by avoiding trauma and by wearing a good supportive brassiere during the night and day. Hormone therapy is not advisable, because it does not cure the condition and has undesirable side effects. Danazol (100-200 mg orally twice daily), a synthetic androgen, is the only treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients with severe pain. This treatment suppresses pituitary gonadotropins, but androgenic effects (acne, edema, hirsutism) usually make this treatment intolerable; in practice, it is rarely used. Similarly, tamoxifen reduces some symptoms of fibrocystic condition, but because of its side effects, it is not useful for young women unless it is given to reduce the risk of cancer. Postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy may stop or change doses of hormones to reduce pain. Oil of evening primrose (OEP), a natural form of gamolenic acid, has been shown to decrease pain in 44%-58% of users. The dosage of gamolenic acid is six capsules of 500 mg orally twice daily. Studies have also demonstrated a low-fat diet or decreasing dietary fat intake may reduce the painful symptoms associated with fibrocystic condition. Further research is being done to determine the effects of topical treatments such as topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as well as topical hormonal drugs such as topical tamoxifen.

The role of caffeine consumption in the development and treatment of fibrocystic condition is controversial. Some studies suggest that eliminating caffeine from the diet is associated with improvement while other studies refute the benefit entirely. Many patients are aware of these studies and report relief of symptoms after giving up coffee, tea, and chocolate. Similarly, many women find vitamin E (400 international units daily) helpful; however, these observations remain anecdotal.

Exacerbations of pain, tenderness, and cyst formation may occur at any time until menopause, when symptoms usually subside, except in patients receiving hormonal replacement. The patient should be advised to examine her own breasts regularly just after menstruation and to inform her practitioner if a mass appears. The risk of breast cancer developing in women with fibrocystic condition with a proliferative or atypical component in the epithelium or papillomatosis is higher than that of the general population. These women should be monitored carefully with physical examinations and imaging studies.

[PubMed: 20084540]

[PubMed: 20359269]

[PubMed: 22963023]

This common benign neoplasm occurs most frequently in young women, usually within 20 years after puberty. It is somewhat more frequent and tends to occur at an earlier age in black women. Multiple tumors are found in 10%-15% of patients.

The typical fibroadenoma is a round or ovoid, rubbery, discrete, relatively movable, nontender mass 1-5 cm in diameter. It is usually discovered accidentally. Clinical diagnosis in young patients is generally not difficult. In women over 30 years, fibrocystic condition of the breast and carcinoma of the breast must be considered. Cysts can be identified by aspiration or ultrasonography. Fibroadenoma does not normally occur after menopause but may occasionally develop after administration of hormones.

No treatment is usually necessary if the diagnosis can be made by needle biopsy or cytologic examination. Excision with pathologic examination of the specimen is performed if the diagnosis is uncertain. Cryoablation, or freezing of the fibroadenoma, appears to be a safe procedure if the lesion is consistent with fibroadenoma on histology prior to ablation. Cryoablation is not appropriate for all fibroadenomas because some are too large to freeze or the diagnosis may not be certain. There is no obvious advantage to cryoablation of a histologically proven fibroadenoma except that some patients may feel relief that a mass is gone. However, at times a mass of scar or fat necrosis replaces the mass of the fibroadenoma. Reassurance seems preferable. It is usually not possible to distinguish a large fibroadenoma from a phyllodes tumor on the basis of needle biopsy results or imaging alone.

Phyllodes tumor is a fibroadenoma-like tumor with cellular stroma that grows rapidly. It may reach a large size and, if inadequately excised, will recur locally. The lesion can be benign or malignant. If benign, phyllodes tumor is treated by local excision with a margin of surrounding breast tissue. The treatment of malignant phyllodes tumor is more controversial, but complete removal of the tumor with a rim of normal tissue avoids recurrence. Because these tumors may be large, simple mastectomy is sometimes necessary. Lymph node dissection is not performed, since the sarcomatous portion of the tumor metastasizes to the lungs and not the lymph nodes.

[PubMed: 22121516]

[PubMed: 20094997]

[PubMed: 19434472]

In order of decreasing frequency, the following are the most common causes of nipple discharge in the nonlactating breast: duct ectasia, intraductal papilloma, and carcinoma. The important characteristics of the discharge and some other factors to be evaluated by history and physical examination are listed in Table 17–1.

| Finding | Significance |

|---|---|

| Serous | Most likely benign FCC, ie, duct ectasia |

| Bloody | More likely neoplastic–papilloma, carcinoma |

| Associated mass | More likely neoplastic |

| Unilateral | Either neoplastic or non-neoplastic |

| Bilateral | Most likely non-neoplastic |

| Single duct | More likely neoplastic |

| Multiple ducts | More likely FCC |

| Milky | Endocrine disorders, medications |

| Spontaneous | Either neoplastic or non-neoplastic |

| Produced by pressure at single site | Either neoplastic or non-neoplastic |

| Persistent | Either neoplastic or non-neoplastic |

| Intermittent | Either neoplastic or non-neoplastic |

| Related to menses | More likely FCC |

| Premenopausal | More likely FCC |

| Taking hormones | More likely FCC |

Spontaneous, unilateral, serous or serosanguineous discharge from a single duct is usually caused by an intraductal papilloma or, rarely, by an intraductal cancer. A mass may not be palpable. The involved duct may be identified by pressure at different sites around the nipple at the margin of the areola. Bloody discharge is suggestive of cancer but is more often caused by a benign papilloma in the duct. Cytologic examination may identify malignant cells, but negative findings do not rule out cancer, which is more likely in women over age 50 years. In any case, the involved bloody duct—and a mass if present—should be excised. A ductogram (a mammogram of a duct after radiopaque dye has been injected) is of limited value since excision of the suspicious ductal system is indicated regardless of findings. Ductoscopy, evaluation of the ductal system with a small scope inserted through the nipple, has been attempted but is not effective management.

In premenopausal women, spontaneous multiple duct discharge, unilateral or bilateral, most noticeable just before menstruation, is often due to fibrocystic condition. Discharge may be green or brownish. Papillomatosis and ductal ectasia are usually detected only by biopsy. If a mass is present, it should be removed.

A milky discharge from multiple ducts in the nonlactating breast may occur from hyperprolactinemia. Serum prolactin levels should be obtained to search for a pituitary tumor. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) helps exclude causative hypothyroidism. Numerous antipsychotic drugs and other drugs may also cause a milky discharge that ceases on discontinuance of the medication.

Oral contraceptive agents or estrogen replacement therapy may cause clear, serous, or milky discharge from a single duct, but multiple duct discharge is more common. In the premenopausal woman, the discharge is more evident just before menstruation and disappears on stopping the medication. If it does not stop, is from a single duct, and is copious, exploration should be performed since this may be a sign of cancer.

A purulent discharge may originate in a subareolar abscess and require removal of the abscess and the related lactiferous sinus.

When localization is not possible, no mass is palpable, and the discharge is nonbloody, the patient should be reexamined every 3 or 4 months for a year, and a mammogram and an ultrasound should be performed. Although most discharge is from a benign process, patients may find it annoying or disconcerting. To eliminate the discharge, proximal duct excision can be performed both for treatment and diagnosis.

[PubMed: 21947751]

[PubMed: 20012502]

[PubMed: 20354781]

[PubMed: 20079481]

[PubMed: 20050819]

Fat necrosis is a rare lesion of the breast but is of clinical importance because it produces a mass (often accompanied by skin or nipple retraction) that is usually indistinguishable from carcinoma even with imaging studies. Trauma is presumed to be the cause, though only about 50% of patients give a history of injury. Ecchymosis is occasionally present. If untreated, the mass effect gradually disappears. The safest course is to obtain a biopsy. Needle biopsy is often adequate, but frequently the entire mass must be excised, primarily to exclude carcinoma. Fat necrosis is common after segmental resection, radiation therapy, or flap reconstruction after mastectomy.

During nursing, an area of redness, tenderness, and induration may develop in the breast. The organism most commonly found in these abscesses is Staphylococcus aureus.

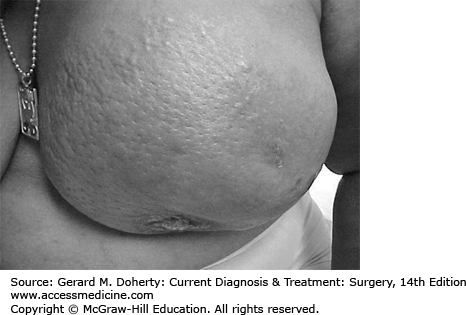

Infection in the nonlactating breast is rare. A subareolar abscess may develop in young or middle-aged women who are not lactating (Figure 17–1). These infections tend to recur after incision and drainage unless the area is explored during a quiescent interval, with excision of the involved lactiferous duct or ducts at the base of the nipple. In the nonlactating breast, inflammatory carcinoma must always be considered. Thus, incision and biopsy of any indurated tissue with a small piece of erythematous skin is indicated when suspected abscess or cellulitis in the nonlactating breast does not resolve promptly with antibiotics. Often needle or catheter drainage is adequate to treat an abscess, but surgical incision and drainage may be necessary.

[PubMed: 21997989]

[PubMed: 20349659]

At least 4 million American women have had breast implants. Breast augmentation is performed by placing implants under the pectoralis muscle or, less desirably, in the subcutaneous tissue of the breast. Most implants are made of an outer silicone shell filled with a silicone gel, saline, or some combination of the two. Capsule contraction or scarring around the implant develops in about 15%-25% of patients, leading to a firmness and distortion of the breast that can be painful. Some require removal of the implant and surrounding capsule.

Implant rupture may occur in as many as 5%-10% of women, and bleeding of gel through the capsule is noted even more commonly. Although silicone gel may be an immunologic stimulant, there is no increase in autoimmune disorders in patients with such implants. The FDA has advised symptomatic women with ruptured silicone implants to discuss possible surgical removal with their clinicians. However, women who are asymptomatic and have no evidence of rupture of a silicone gel prosthesis should probably not undergo removal of the implant. Women with symptoms of autoimmune illnesses often undergo removal, but no benefit has been shown.

Studies have failed to show any association between implants and an increased incidence of breast cancer. However, breast cancer may develop in a patient with an augmentation prosthesis, as it does in women without them. Detection in patients with implants is more difficult because mammography is less able to detect early lesions. Mammography is better if the implant is subpectoral rather than subcutaneous. The prosthesis should be placed retropectorally after mastectomy to facilitate detection of a local recurrence of cancer, which is usually cutaneous or subcutaneous and is easily detected by palpation. Recently there has been an association of lymphoma of the breast with silicone implants.

If a cancer develops in a patient with implants, it should be treated in the same manner as in women without implants. Such women should be offered the option of mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy, which may require removal or replacement of the implant. Radiotherapy of the augmented breast often results in marked capsular contracture. Adjuvant treatments should be given for the same indications as for women who have no implants.

[PubMed: 18984890]

[JAMA and JAMA Network Journals Full Text]

[PubMed: 23012658]

[PubMed: 23235342]

[PubMed: 21427311]

[PubMed: 19884555]

CARCINOMA OF THE FEMALE BREAST

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Risk factors include delayed childbearing, positive family history of breast cancer or genetic mutations (BRCA1, BRCA2), and personal history of breast cancer or some types of proliferative conditions.

Early findings: Single, nontender, firm to hard mass with ill-defined margins; mammographic abnormalities and no palpable mass.

Later findings: Skin or nipple retraction; axillary lymphadenopathy; breast enlargement, erythema, edema, pain; fixation of mass to skin or chest wall.

Breast cancer will develop in one of eight American women. Next to skin cancer, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women; it is second only to lung cancer as a cause of death. In 2012, there were approximately 229,060 new cases and 39,920 deaths from breast cancer in women in the United States. An additional 63,300 cases of breast carcinoma in situ were detected, principally by screening mammography. Worldwide, breast cancer is diagnosed in approximately 1.38 million women, and about 458,000 die of breast cancer each year, with the highest rates of diagnosis in Western and Northern Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America and lowest rates in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. These regional differences in incidence are likely due to the variable availability of screening mammography as well as differences in reproductive and hormonal factors. In Western countries, incidence rates decreased with a reduced use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and mortality declined with increased use of screening and improved treatments. In contrast, incidence and mortality from breast cancer in many African and Asian countries has increased as reproductive factors have changed (such as delayed childbearing) and as the incidence of obesity has risen.

The most significant risk factor for the development of breast cancer is age. A woman’s risk of breast cancer rises rapidly until her early 60s, peaks in her 70s, and then declines. A significant family history of breast or ovarian cancer may also indicate a high risk of developing breast cancer. Germline mutations in the BRCA family of tumor suppressor genes accounts for approximately 5%-10% of breast cancer diagnoses and tend to cluster in certain ethnic groups, including women of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Women with a mutation in the BRCA1 gene, located on chromosome 17, have an estimated 85% chance of developing breast cancer in their lifetime. Other genes associated with an increased risk of breast and other cancers include BRCA2 (associated with a gene on chromosome 13); ataxia-telangiectasia mutation; and mutation of the tumor suppressor gene p53. If a woman has a compelling family history (such as breast cancer diagnosed in two first-degree relatives, especially if diagnosed younger than age 50; ovarian cancer; male breast cancer; or a first-degree relative with bilateral breast cancer), genetic testing may be appropriate. In general, it is best for a woman who has a strong family history to meet with a genetics counselor to undergo a risk assessment and decide whether genetic testing is indicated.

Even when genetic testing fails to reveal a predisposing genetic mutation, women with a strong family history of breast cancer are at higher risk for development of breast cancer. Compared with a woman with no affected family members, a woman who has one first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or sister) with breast cancer has double the risk of developing breast cancer and a woman with two first-degree relatives with breast cancer has triple the risk of developing breast cancer. The risk is further increased for a woman whose affected family member was premenopausal at the time of diagnosis or had bilateral breast cancer. Lifestyle and reproductive factors also contribute to risk of breast cancer. Nulliparous women and women whose first full-term pregnancy occurred after the age of 30 have an elevated risk. Late menarche and artificial menopause are associated with a lower incidence, whereas early menarche (under the age of 12) and late natural menopause (after the age of 55) are associated with an increase in risk. Combined oral contraceptive pills may increase the risk of breast cancer. Several studies show that concomitant administration of progesterone and estrogen to postmenopausal women may markedly increase the incidence of breast cancer, compared with the use of estrogen alone or with no hormone replacement treatment. The Women’s Health Initiative prospective randomized study of hormone replacement therapy stopped treatment with estrogen and progesterone early because of an increased risk of breast cancer compared with untreated women or women treated with estrogen alone. Alcohol consumption, high dietary intake of fat, and lack of exercise may also increase the risk of breast cancer. Fibrocystic breast condition, when accompanied by proliferative changes, papillomatosis, or atypical epithelial hyperplasia, and increased breast density on mammogram are also associated with an increased incidence. A woman who had cancer in one breast is at increased risk for cancer developing in the other breast. In these women, a contralateral cancer develops at the rate of 1% or 2% per year. Women with cancer of the uterine corpus have a risk of breast cancer significantly higher than that of the general population, and women with breast cancer have a comparably increased risk of endometrial cancer. Socioeconomic and racial factors have also been associated with breast cancer risk. Breast cancer tends to be diagnosed more frequently in women of higher socioeconomic status and is more frequent in white women than in black women.

Women at greater than average risk for developing breast cancer (Table 17–2) should be identified by their practitioners and monitored carefully. Risk assessment models have been developed and several have been validated (most extensively the Gail 2 model) to evaluate a woman’s risk of developing cancer. Those with an exceptional family history should be counseled about the option of genetic testing. Some of these high-risk women may consider prophylactic mastectomy, oophorectomy, or tamoxifen, an FDA-approved preventive agent. The Prevention and Observation of Surgical Endpoints (PROSE) consortium monitored women with deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations from 1974 to 2008 and reported that 15% of women with a known BRCA mutation underwent bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, and none of them developed breast cancer during the 3 years of follow-up. In contrast, subsequent breast cancer developed in 98 (7%) of the 1372 women who did not have surgery. Moreover, women who underwent prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy had a lower risk of ovarian cancer, all-cause mortality, as well as breast cancer- and ovarian cancer-specific mortality.

| Race | White |

| Age | Older |

| Family history | Breast cancer in parent, sibling, or child especially bilateral or premenopausal) |

| Genetics | BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation |

| Previous medical history | Endometrial cancer Proliferative forms of fibrocystic disease Cancer in other breast |

| Menstrual history | Early menarche (under age 12) Late menopause (after age 50) |

| Reproductive history | Nulliparous or late first pregnancy |

Women with genetic mutations in whom breast cancer develops may be treated in the same way as women who do not have mutations (ie, lumpectomy), though there is an increased risk of ipsilateral and contralateral recurrence after lumpectomy for these women. One study showed that of patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer who were found to be carriers of a BRCA mutation, approximately 50% chose to undergo bilateral mastectomy.

The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) conducted the first Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) P-1, which evaluated tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), as a preventive agent in women with no personal history of breast cancer but at high risk for developing the disease. Women who received tamoxifen for 5 years had about a 50% reduction in noninvasive and invasive cancers compared with women taking placebo. However, women over age 50 who received the drug had an increased incidence of endometrial cancer and deep venous thrombosis.

The SERM raloxifene, effective in preventing osteoporosis, is also effective in preventing breast cancer. The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial compared raloxifene with tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer in a high-risk population. With a median follow-up of 81 months, raloxifene was associated with a higher risk of invasive breast cancer but had an equivalent risk for noninvasive disease compared with tamoxifen. Uterine cancer, cataracts, and thromboembolic events were significantly lower in the raloxifene-treated patients than in tamoxifen-treated patients. While SERMs have been shown to be effective at reducing the risk of breast cancer, the uptake of this intervention by women has been relatively low, possibly due to the perceived risks and side effects of therapy. A cost-effectiveness study based on a meta-analysis of four randomized prevention trials showed that tamoxifen saves costs and improves life expectancy when higher risk (Gail 5-year risk at least 1.66%) women under the age of 55 years were treated.

Similar to SERMs, aromatase inhibitors (AI) such as exemestane have shown great success in preventing breast cancer with a lower risk of uterine cancer and thromboembolic events, although bone loss is a significant side effect of this treatment. In an international phase III clinical trial, 4560 postmenopausal women at high risk for breast cancer were randomly assigned to receive exemestane or placebo for 5 years. “High risk” was defined as at least one of the following: at least 60 years of age, Gail 5-year risk score > 1.66%; prior atypical ductal or lobular hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS); or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with mastectomy. With a median follow up of 35 months, there was a 65% relative risk reduction in the annual risk of invasive breast cancer (0.19% vs 0.55%; hazard ratio, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.18, 0.70; P = 0.002) for patients who received exemestane. While exemestane use was associated with a higher rate of adverse events (88% vs 85%; P = 0.003), there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of skeletal fractures or cardiovascular events, though longer follow up is needed to accurately assess these outcomes. Based on these data, exemestane is a reasonable risk-reducing option for postmenopausal women at higher risk for breast cancer.

[PubMed: 22460733]

[PubMed: 21639806]

[PubMed: 21296855]

[PubMed: 22037780]

[PubMed: 21717445]

[PubMed: 22237781]

[PubMed: 20404000]

A number of large screening programs, consisting of physical and mammographic examination of asymptomatic women, have been conducted over the years. On average, these programs identify 10 cancers per 1000 women over the age of 50 and 2 cancers per 1000 women under the age of 50. Screening detects cancer before it has spread to the lymph nodes in about 80% of the women evaluated. This increases the chance of survival to about 85% at 5 years.

About one-third of the abnormalities detected on screening mammograms will be found to be malignant when biopsy is performed. The probability of cancer on a screening mammogram is directly related to the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) assessment, and workup should be performed based on this classification. Women 20-40 years of age should have a breast examination as part of routine medical care every 2-3 years. Women over age 40 years should have annual breast examinations. The sensitivity of mammography varies from approximately 60%-90%. This sensitivity depends on several factors, including patient’s age (breast density) and tumor size, location, and mammographic appearance. In young women with dense breasts, mammography is less sensitive than in older women with fatty breasts, in whom mammography can detect at least 90% of malignancies. Smaller tumors, particularly those without calcifications, are more difficult to detect, especially in dense breasts. The lack of sensitivity and the low incidence of breast cancer in young women have led to questions concerning the value of mammography for screening in women 40-50 years of age. The specificity of mammography in women under 50 years varies from about 30%-40% for nonpalpable mammographic abnormalities to 85%-90% for clinically evident malignancies. In 2009, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended against routine screening mammography in this age range, and also recommended mammography be performed every 2 years for women between the ages of 50 and 74. The change in recommendation for screening women age 40-50 were particularly controversial in light of several meta-analyses that included women in this age group and showed a 15%-20% reduction in the relative risk of death from breast cancer with screening mammography. To add to the controversy, an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database from 1976 to 2008 suggests that screening mammography has led to substantial increases in the number of breast cancer cases diagnosed but has only had a minor impact on the rate of women presenting with advanced disease. These data should all be taken into consideration when advising a patient regarding the utility of screening mammography. The American Cancer Society continues to recommend yearly mammography for women beginning at the age of 40, continuing as long as good health lasts.

Breast self-examination (BSE) has not been shown to improve survival. Because of the lack of strong evidence demonstrating value, the American Cancer Society no longer recommends monthly BSE. The recommendation is that patients be made aware of the potential benefits, limitations, and harms (increased biopsies or false-positive results) associated with BSE. Women who choose to perform BSE should be advised regarding the proper technique. Premenopausal women should perform the examination 7-8 days after the start of the menstrual period. First, breasts should be inspected before a mirror with the hands at the sides, overhead, and pressed firmly on the hips to contract the pectoralis muscles causing masses, asymmetry of breasts, and slight dimpling of the skin to become apparent. Next, in a supine position, each breast should be carefully palpated with the fingers of the opposite hand. Some women discover small breast lumps more readily when their skin is moist while bathing or showering. While BSE is not a recommended practice, patients should recognize and report any breast changes to their clinicians as it remains an important facet of proactive care. A small number of studies have reported a reduction in breast cancer mortality with screening clinical breast examination (CBE). While the evidence is only fair, in contrast to BSE, the ACS recommends CBE every 3 years in women ages 20-39 and annually starting at the age of 40.

Mammography is the most reliable means of detecting breast cancer before a mass can be palpated. Most slowly growing cancers can be identified by mammography at least 2 years before reaching a size detectable by palpation. Film screen mammography delivers < 0.4 cGy to the mid-breast per view. Although full-field digital mammography provides an easier method to maintain and review mammograms, it has not been proven that it provides better images or increases detection rates more than film mammography. In subset analysis of a large study, digital mammography seemed slightly superior in women with dense breasts. Computer-assisted detection has not shown any increase in detection of cancers.

Calcifications are the most easily recognized mammographic abnormality. The most common findings associated with carcinoma of the breast are clustered pleomorphic microcalcifications. Such calcifications are usually at least five to eight in number, aggregated in one part of the breast and differing from each other in size and shape, often including branched or V- or Y-shaped configurations. There may be an associated mammographic mass density or, at times, only a mass density with no calcifications. Such a density usually has irregular or ill-defined borders and may lead to architectural distortion within the breast but may be subtle and difficult to detect.

Indications for mammography are as follows: (1) to screen at regular intervals asymptomatic women at high risk for developing breast cancer (see above); (2) to evaluate each breast when a diagnosis of potentially curable breast cancer has been made, and at regular intervals thereafter; (3) to evaluate a questionable or ill-defined breast mass or other suspicious change in the breast; (4) to search for an occult breast cancer in a woman with metastatic disease in axillary nodes or elsewhere from an unknown primary; (5) to screen women prior to cosmetic operations or prior to biopsy of a mass, to examine for an unsuspected cancer; (6) to monitor those women with breast cancer who have been treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiation; and (7) to monitor the contralateral breast in those women with breast cancer treated with mastectomy.

Patients with a dominant or suspicious mass must undergo biopsy despite mammographic findings. The mammogram should be obtained prior to biopsy so that other suspicious areas can be noted and the contralateral breast can be evaluated. Mammography is never a substitute for biopsy because it may not reveal clinical cancer, especially in a very dense breast, as may be seen in young women with fibrocystic changes, and may not reveal medullary cancers.

Communication and documentation among the patient, the referring practitioner, and the interpreting physician are critical for high-quality screening and diagnostic mammography. The patient should be told about how she will receive timely results of her mammogram; that mammography does not “rule out” cancer; and that she may receive a correlative examination such as ultrasound at the mammography facility if referred for a suspicious lesion. She should also be aware of the technique and need for breast compression and that this may be uncomfortable. The mammography facility should be informed in writing by the clinician of abnormal physical examination findings. The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) Clinical Practice Guidelines strongly recommend that all mammography reports be communicated in writing to the patient and referring practitioner.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound may be useful screening modalities in women who are at high risk for breast cancer but not for the general population. The sensitivity of MRI is much higher than mammography; however, the specificity is significantly lower and this results in multiple unnecessary biopsies. The increased sensitivity despite decreased specificity may be considered a reasonable trade-off for those at increased risk for developing breast cancer but not for normal-risk population. In 2009, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommended MRI in addition to screening mammography for high-risk women, including those with BRCA1/2 mutations, those who have a lifetime risk of breast cancer of > 20%, and those with a personal history of LCIS. Women who received radiation therapy to the chest in their teens or twenties are also known to be at high risk for developing breast cancer and screening MRI may be considered in addition to mammography. MRI is useful in women with breast implants to determine the character of a lesion present in the breast and to search for implant rupture and at times is helpful in patients with prior lumpectomy and radiation.

[PubMed: 21901178]

[PubMed: 23171096]

[PubMed: 21257850]

[PubMed: 20656831]

[PubMed: 20860502]

[PubMed: 21246531]

[PubMed: 22098853]

[PubMed: 21916640]

The presenting complaint in about 70% of patients with breast cancer is a lump (usually painless) in the breast. About 90% of these breast masses are discovered by the patient. Less frequent symptoms are breast pain; nipple discharge; erosion, retraction, enlargement, or itching of the nipple; and redness, generalized hardness, enlargement, or shrinking of the breast. Rarely, an axillary mass or swelling of the arm may be the first symptom. Back or bone pain, jaundice, or weight loss may be the result of systemic metastases, but these symptoms are rarely seen on initial presentation.

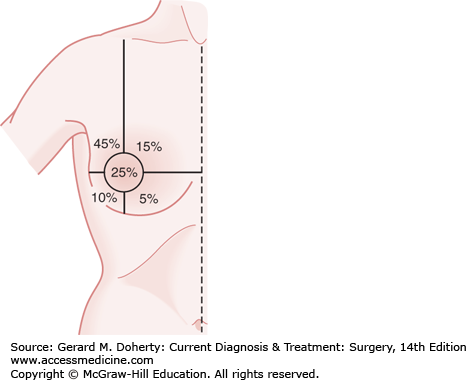

The relative frequency of carcinoma in various anatomic sites in the breast is shown in Figure 17–2.

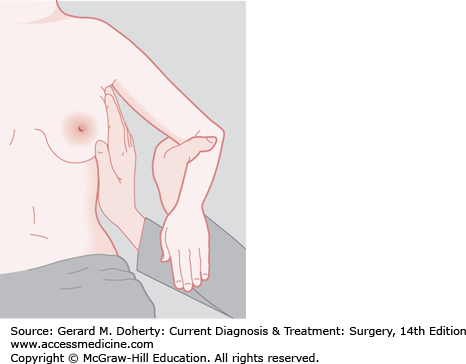

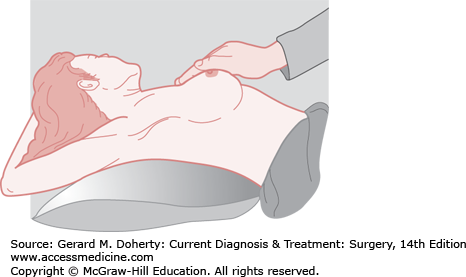

Inspection of the breast is the first step in physical examination and should be carried out with the patient sitting, arms at her sides, and then overhead. Abnormal variations in breast size and contour, minimal nipple retraction, and slight edema, redness or retraction of the skin can be identified (Figure 17–3). Asymmetry of the breasts and retraction or dimpling of the skin can often be accentuated by having the patient raise her arms overhead or press her hands on her hips to contract the pectoralis muscles. Axillary and supraclavicular areas should be thoroughly palpated for enlarged nodes with the patient sitting (Figure 17–4). Palpation of the breast for masses or other changes should be performed with the patient both seated and supine with the arm abducted (Figure 17–5). Palpation with a rotary motion of the examiner’s fingers as well as a horizontal stripping motion has been recommended.

Breast cancer usually consists of a nontender, firm or hard mass with poorly delineated margins (caused by local infiltration). Very small (1-2 mm) erosions of the nipple epithelium may be the only manifestation of Paget disease of the breast. Watery, serous, or bloody discharge from the nipple is an occasional early sign but is more often associated with benign disease.

A small lesion, less than 1 cm in diameter, may be difficult or impossible for the examiner to feel but may be discovered by the patient. She should always be asked to demonstrate the location of the mass; if the practitioner fails to confirm the patient’s suspicions and imaging studies are normal, the examination should be repeated in 2-3 months, preferably 1-2 weeks after the onset of menses. During the premenstrual phase of the cycle, increased innocuous nodularity may suggest neoplasm or may obscure an underlying lesion. If there is any question regarding the nature of an abnormality under these circumstances, the patient should be asked to return after her menses. Ultrasound is often valuable and mammography essential when an area is felt by the patient to be abnormal but the physician feels no mass. MRI may be considered, but the lack of specificity should be discussed by the clinician and the patient. MRI should not be used to rule out cancer because MRI has a false-negative rate of about 3%-5%. Although lower than mammography, this false-negative rate cannot permit safe elimination of the possibility of cancer. False negatives are more likely seen in infiltrating lobular carcinomas and DCIS.

Metastases tend to involve regional lymph nodes, which may be palpable. One or two movable, nontender, not particularly firm axillary lymph nodes 5 mm or less in diameter are frequently present and are generally of no significance. Firm or hard nodes larger than 1 cm are typical of metastases. Axillary nodes that are matted or fixed to skin or deep structures indicate advanced disease (at least stage III). On the other hand, if the examiner thinks that the axillary nodes are involved, that impression will be borne out by histologic section in about 85% of cases. The incidence of positive axillary nodes increases with the size of the primary tumor. Noninvasive cancers (in situ) do not metastasize. Metastases are present in about 30% of patients with clinically negative nodes.

In most cases, no nodes are palpable in the supraclavicular fossa. Firm or hard nodes of any size in this location or just beneath the clavicle should be biopsied. Ipsilateral supraclavicular or infraclavicular nodes containing cancer indicate that the tumor is in an advanced stage (stage III or IV). Edema of the ipsilateral arm, commonly caused by metastatic infiltration of regional lymphatics, is also a sign of advanced cancer.

Liver or bone metastases may be associated with elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase. Hypercalcemia is an occasional important finding in advanced cancer of the breast. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA 15-3 or CA 27-29 may be used as markers for recurrent breast cancer but are not helpful in diagnosing early lesions. Investigational breast cancer markers through proteomics and hormone assays may prove to be helpful in early detection or evaluation of prognosis.

For patients with suspicious symptoms or signs (bone pain, abdominal symptoms, elevated liver enzymes) or locally advanced disease (clinically abnormal lymph nodes or large primary tumors), staging scans are indicated prior to surgery or systemic therapy. Chest imaging with CT or radiographs may be done to evaluate for pulmonary metastases. Abdominal imaging with CT or ultrasound may be obtained to evaluate for liver metastases. Bone scans using 99m

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree