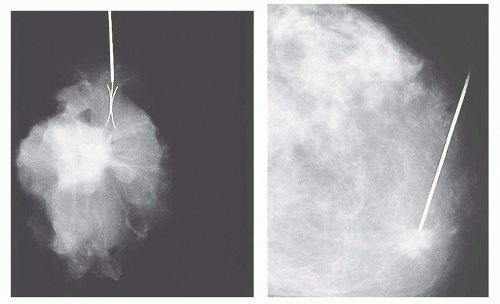

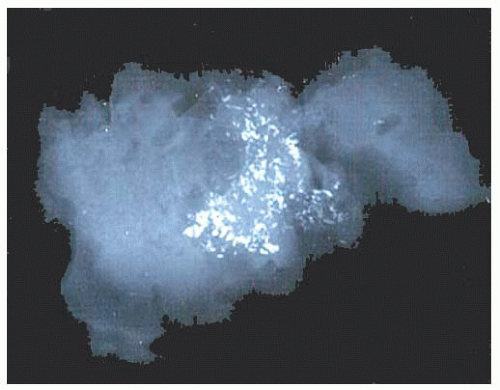

and localization of calcium deposits with the result that the proportion of indeterminate and inadequate specimens is far less. Distinction between in situ and invasive carcinoma may also be more readily accomplished, and predictive markers (estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], HER2/neu, etc.) can be better evaluated. However, FNA may be done more quickly with a diagnosis of malignancy at the time of outpatient visit. In the evaluation of CNB, problems are encountered because of the limited size of the specimens and, not infrequently, the presence of crush artifact. Other problems include potential destruction of lesional tissue by hemorrhage or infarction and displacement of benign epithelium to simulate invasive carcinoma (3), although displacement of epithelium has also been reported following localization by guide-wire for excision of a mammographic abnormality (4). CNB of nonpalpable lesions requires radiographic guidance by either ultrasonography or stereotactic mammography. In CNB performed to evaluate microcalcification, it is important that the calcifications be identified on specimen radiographs (5) and confirmed in the histologic sections, even though calcifications imaged on radiographs are often larger than those seen histologically. Calcification is rarely seen in FNA. Uncertainty in the interpretation of a CNB or the finding of significant atypia should lead to open biopsy. In patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy, CNB specimens may be the only histologic evidence of cancer if there is a complete response.

TABLE 9.1 Features to be Recorded on Gross Examination of a Breast Biopsy Specimen | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 9.2 Contrasting Gross Features of Typical Infiltrating Ductal Carcinoma and Fibroadenoma | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 9.3 Benign Lesions That Most Frequently Mimic Carcinoma on Gross Examination | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

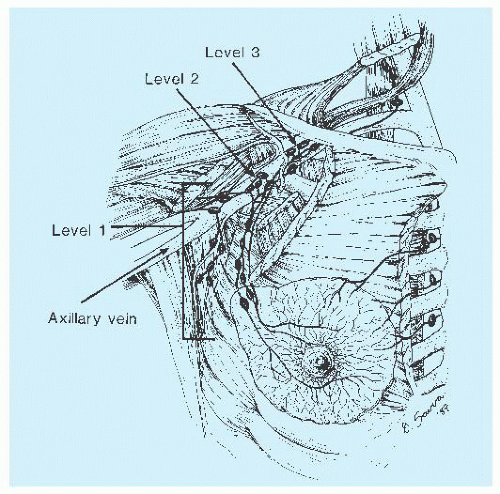

imaging and clearing methods, may increase the yield of lymph nodes. Examination of multiple levels of each block of lymph nodes and immunohistochemical study with the use of epithelial markers may help detect small metastases, but the significance of discovery of micrometastases gained by these laborious techniques is of limited clinical consequence (8). Conservation treatment of mammary carcinoma often includes axillary dissection. The tissue containing the nodes may be removed in continuity with that containing the carcinoma; more often, it is separate. Careful orientation of the specimen, as previously described, may be important.

TABLE 9.4 Contrasting Mammographic Appearances of Carcinoma and Benign Lesions | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

radiography should be performed while the patient is still in the operating room so that further tissue can be removed if necessary. An x-ray image of the specimen should be sent along with the specimen to the pathologist, with the area in question clearly indicated.

microscope can be used to examine the tissue slices, and abnormal areas may be selected for further histologic examination. Similar techniques for the stereoscopic examination of paraffin-embedded tissue blocks have also been reported and are used to evaluate the distribution of pathologic lesions in the mammary tree (16,17).

TABLE 9.5 Most Common Uses of Immunohistochemistry in Breast Pathology | ||

|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 9.6 Features to Be Recorded on Histologic Examination of Invasive Breast Carcinoma | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

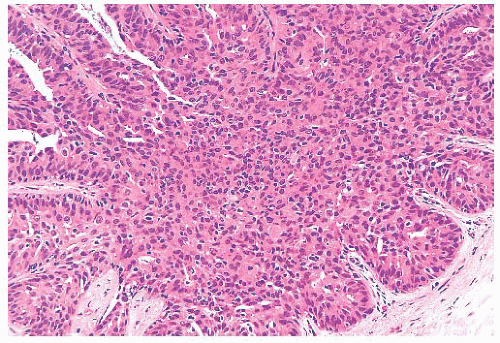

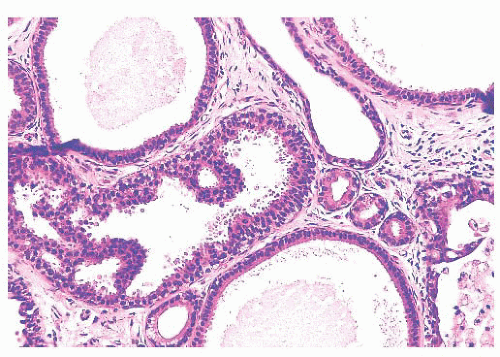

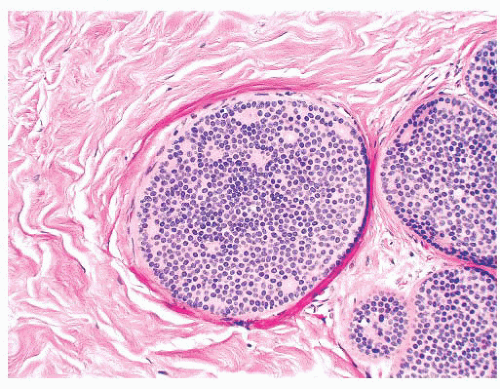

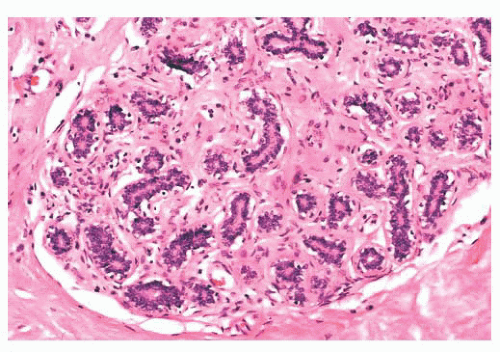

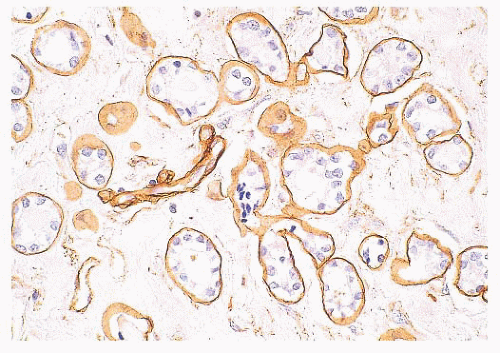

by immunohistochemical methods with antibodies to actins, calponin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, high-molecularweight cytokeratins, and p63. Epithelial cells are differentiated by their keratin profile and staining for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15). The size of the mammary lobules and the number of acini are extremely variable. This may be partly related to the patient’s age, but also to the plane of the section.

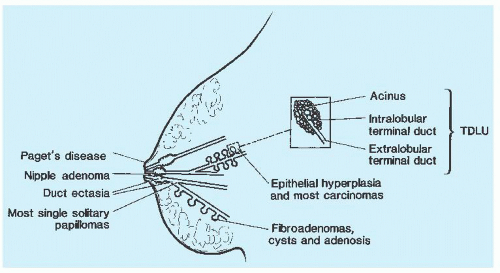

FIGURE 9.7 A schematic representation of the breast indicating the sites of origin of pathologic lesions. |

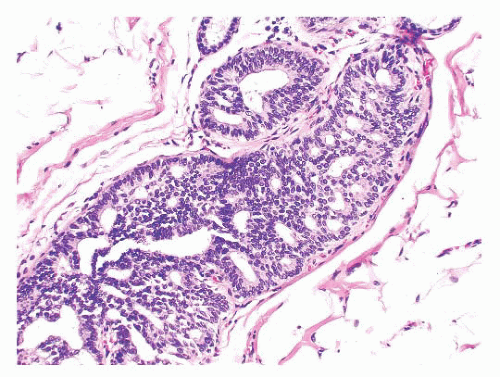

FIGURE 9.9 Lobule in late proliferative phase. Lobular stroma is denser and more fibrous. Epithelial/myoepithelial layers are clearly evident. |

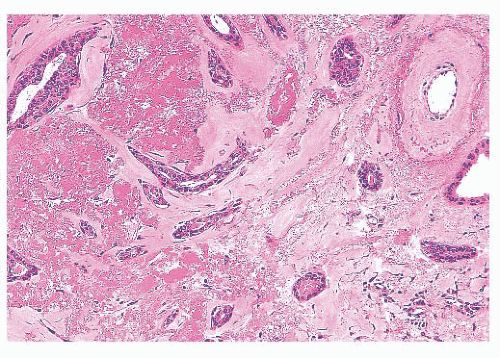

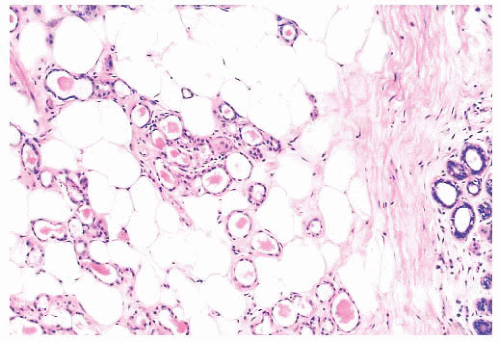

after the menopause, gradual atrophy of the lobular acini occurs, together with a loss of specialized intralobular stroma. The postmenopausal breast eventually atrophies to consist largely of adipose tissue containing a few residual ducts and vessels in interlobular stroma. Occasionally, an isolated lobule showing secretory changes may be seen in the nonpregnant breast. Although this is often called a residual lactating lobule, it may occur in a nulliparous woman.

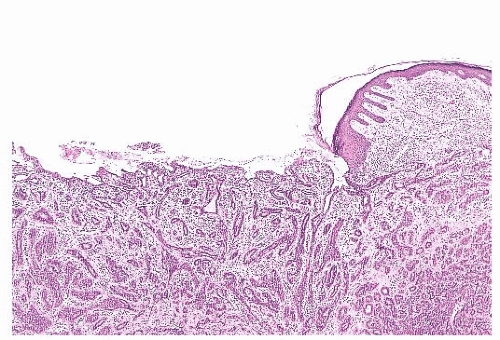

define the cells as those of malignant melanoma. Direct invasion of the epidermis by an underlying carcinoma is not Paget disease.

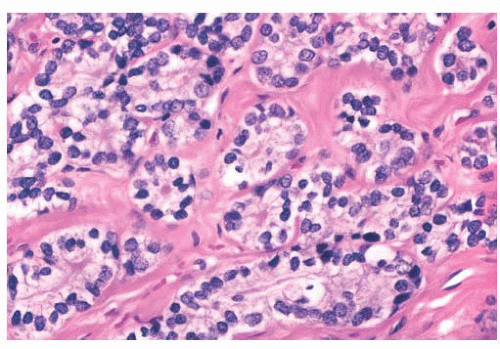

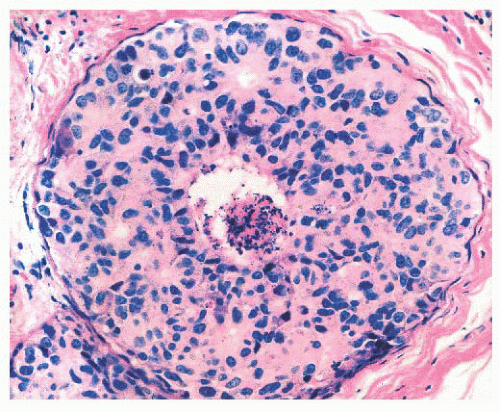

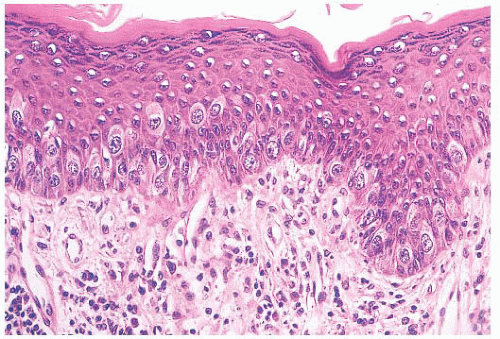

FIGURE 9.11 Paget disease of the nipple. The epidermis is infiltrated by large Paget cells with abundant pale cytoplasm, large vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. |

TABLE 9.7 Histochemical and Immunohistochemical Stains Helpful in the Differential Diagnosis of Paget Disease of the Nipple, Bowen Disease, and Superficial Spreading Malignant Melanoma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

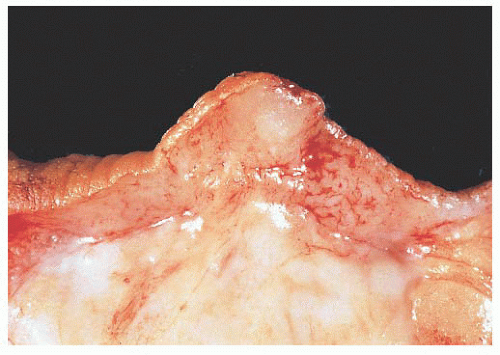

FIGURE 9.13 Nipple adenoma. In this photograph of a nipple specimen, a rounded gray-white nodule is seen immediately below the nipple skin. |

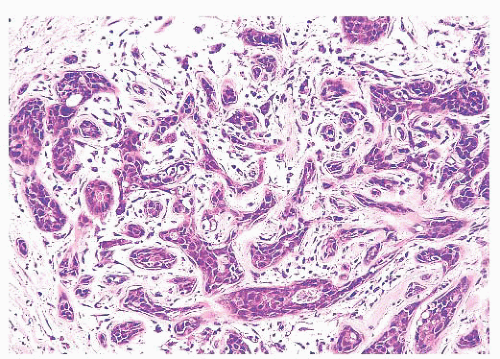

They are of various sizes and shapes, simulating infiltrating carcinoma. Lobular architecture is lacking, probably because the lesion arises from the larger ducts.

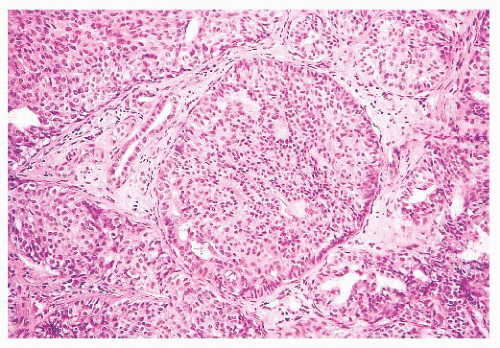

FIGURE 9.15 Nipple adenoma. This high-power view shows the marked degree of epithelial hyperplasia that may be seen in these lesions. |

TABLE 9.8 Contrasting Features of Nipple Adenoma (Florid Papillomatosis), Syringomatous Adenoma, and Tubular Carcinoma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

of the breast (see the section “Metaplastic Carcinoma” later in this chapter). It is also similar to microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the nonmammary skin. In the nipple region, syringomatous adenoma appears to behave in a benign fashion, but complete excision with a clear margin is advisable because recurrence of incompletely excised syringomas has been recorded (31,32). Syringomatous adenoma may be histologically confused with tubular carcinoma, which rarely occurs in the nipple. Features helpful in the differential diagnosis of nipple adenoma, syringomatous adenoma, and tubular carcinoma are listed in Table 9.8.

Metaplastic change within the epithelium (e.g., apocrine metaplasia)

Hyperplasia: an increased number of epithelial cells within preexisting glandular components, variously called epithelial hyperplasia, epitheliosis, and papillomatosis

An increased number of glandular components, termed adenosis

Distortion of preexisting glandular components by the stroma

Physiologic hyperplasia. Florid hyperplastic changes seen in the secretory breast (during pregnancy and lactation) may contain large nuclei with prominent nucleoli.

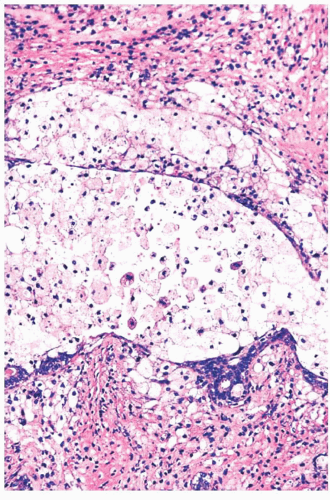

Reactive changes. Occasionally, chronic inflammation around a cyst or in an area of fat necrosis, when viewed at low power, infiltrates into the stroma and thus resembles infiltrating carcinoma.

Benign epithelial hyperplasia of ductal type, which may be mistaken for carcinoma in situ (see section “Epithelial Hyperplasia”).

Benign intraductal papilloma. Differentiation between benign and malignant papillary lesions is frequently difficult. Sclerosis within an intraductal papilloma further compounds the problem and may mimic infiltrating carcinoma. Similar problems can also occur with ductal adenomas (see sections “Papillary Lesions” and “Ductal Adenoma”).

Sclerosing lesions (sclerosing adenosis, radial scar, ductal adenoma), which may be mistaken for infiltrating carcinoma. The presence of apocrine metaplasia or coexisting cancerization by DCIS can cause particular problems (see sections “Sclerosing Adenosis,” “Radial Scar and Complex Sclerosing Lesion,” and “Ductal Carcinoma in Situ”).

Treatment-induced changes. Radiation and chemotherapy may induce distortion and striking nuclear atypia (see section “Changes Induced by Therapy”).

TABLE 9.9 Definitions of Terms Used in Benign Breast Disease | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FIGURE 9.17 Apocrine metaplasia of the luminal epithelium lining cysts. The cells have abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and show apical bleb formation. |

to arise from myoepithelium rather than luminal epithelium (40). Except that their nature should be recognized, apocrine, columnar, clear cell, and squamous cell changes are of no known clinical significance.

In large cysts, the epithelial lining may be partially, if not entirely, lost.

In duct ectasia, an inflammatory reaction around a cyst is accompanied by fibrosis and plasma cells, which can be mistaken for infiltrating carcinoma on low-power examination.

FIGURE 9.22 Cystic change. At higher magnification, the epithelial cells of the duct are almost all destroyed by the inflammatory reaction, and fibrosis is beginning around the duct.

An intense inflammatory reaction consisting mainly of foamy macrophages may be all that remains at the site of a cyst and may be mistaken for fat necrosis.

Elastic tissue can be demonstrated around ectatic ducts.

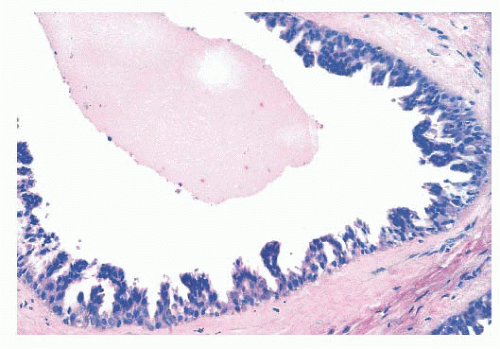

Benign cysts must be differentiated from cystic hypersecretory DCIS.

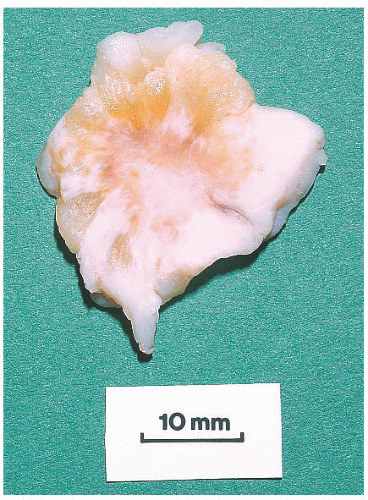

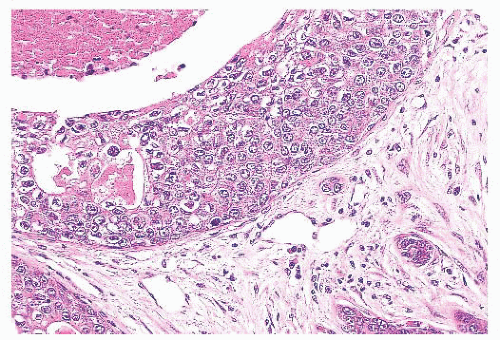

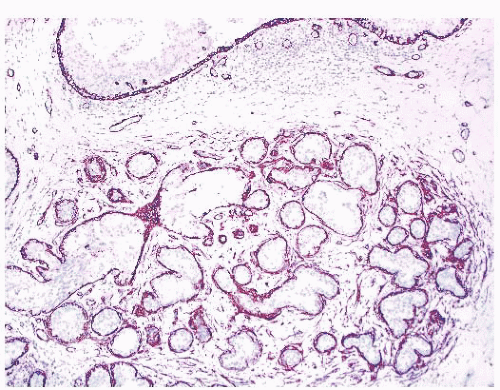

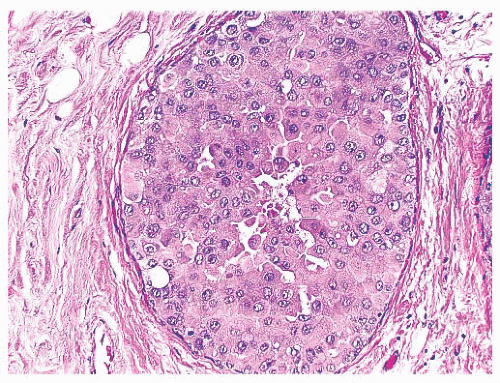

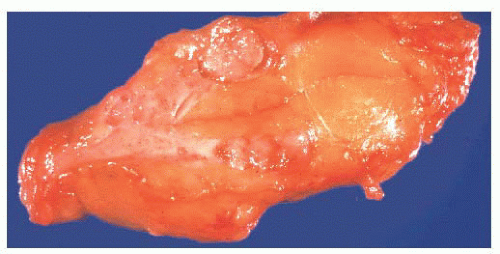

controversial subject. When sclerosing adenosis contains in situ carcinoma, the differential diagnosis from infiltrating carcinoma may be difficult. Features that distinguish sclerosing adenosis from tubular carcinoma are listed in Table 9.10. In difficult cases, immunohistochemistry may help identify myoepithelial cells and basement membranes (Table 9.5). The term nodular adenosis, or adenosis tumor, has been applied to florid examples of sclerosing adenosis that enlarge to form palpable lesions, sometimes seen as rounded, pink, granular areas on gross examination.

FIGURE 9.25 Sclerosing adenosis with perineural invasion. The perineural space is distended by bland epithelium in association with sclerosing adenosis. |

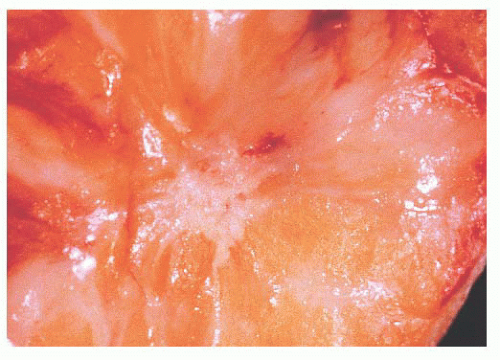

FIGURE 9.27 Radial scar. On gross examination, this stellate lesion closely resembles an infiltrating carcinoma. |

TABLE 9.10 Contrasting Features of Sclerosing Adenosis, Radial Scar, Tubular Carcinoma, and Microglandular Adenosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

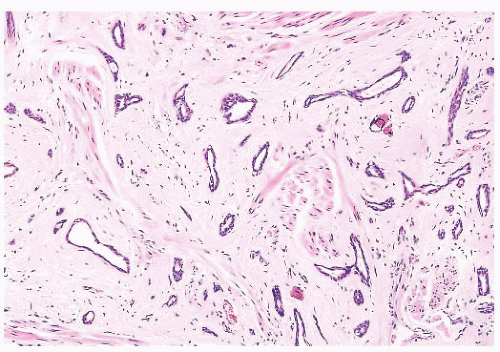

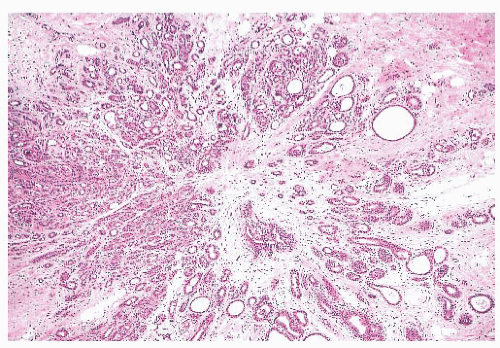

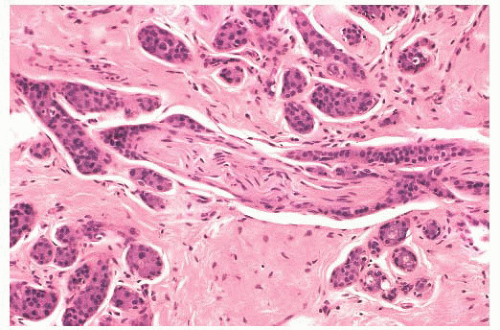

is caused by bands of dense, fibrous connective tissue extending outward from the central core ending in dilated ducts and giving the appearance of a daisy (Fig. 9.28). The characteristic feature is the central elastotic scar containing a few small, entrapped glandular structures, which may simulate tubular carcinoma. However, the entrapped ducts are usually relatively few in number and, at least some of them, can be shown to contain epithelial and myoepithelial layers (Figs. 9.29 and 9.30). They are surrounded by dense collagen and elastosis, which may be a dominant feature. Surrounding the central scar there may be lobules, sometimes distorted by sclerosis, and/or ducts with epithelial hyperplasia, which may be atypical or, rarely, contain intraductal carcinoma. In the outer epithelial components, apocrine metaplasia and calcification may be present. Radial scars are often associated with other benign lesions, particularly sclerosing adenosis. Although the clinical significance of radial scars remains controversial (43,44), most authorities consider them to be benign mimics of cancer (45). However, an increased incidence of carcinoma and atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) appears to be associated with large radial scars, particularly in women older than 50 years (46). In addition, one clinical follow-up study suggested that radial scars are associated with an increased risk for subsequent breast cancer, particularly when found in breasts that exhibit other benign proliferative lesions (47). Therefore, the size and histologic features of radial scar should be recorded with that diagnosis.

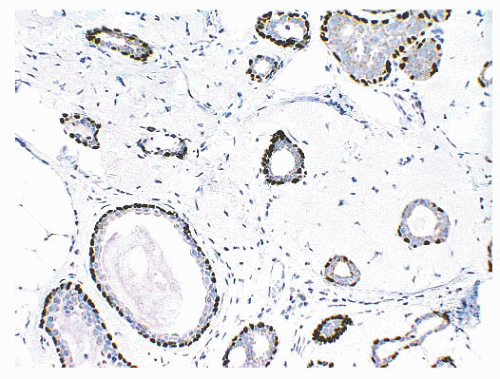

FIGURE 9.30 Radial scar. The entrapped benign glands are surrounded by myoepithelial cells, which show strong nuclear staining for p63. |

(Fig. 9.32), in addition to electron microscopy, confirms the presence of an intact basement membrane around the epithelial structures and the absence of myoepithelial cells. An important feature in the recognition of microglandular adenosis is the absence of a desmoplastic reaction around the tubules. Most reports of microglandular adenosis indicate that it is benign (49,50 and 51), but atypical forms have been described (Fig. 9.33) (atypical microglandular adenosis) (52), and, rarely, carcinoma can arise in or in conjunction with microglandular adenosis (52 and 53).

FIGURE 9.32 Microglandular adenosis. Immunohistochemistry for collagen IV demonstrates a complete ring of basement membrane around individual tubules. |

a study showing considerable disagreement in the evaluation of a small group of proliferative ductal lesions by pathologists (56). Reproducibility can be improved if carefully defined histologic criteria are used (57). Although ancillary techniques, including assessment of proliferative activity, morphometry, and immunohistochemistry with various antibodies (e.g., cytokeratins 5 and 6), have shown some overall differences between the groups, they do not allow clear separation of entities in individual cases.

TABLE 9.11 Contrasting Features of Epithelial Hyperplasia (Epitheliosis) and Ductal Carcinoma in Situ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

carcinoma in situ rests on several features listed in Table 9.12. The presence of outright malignant cells is definitive, but these are only seen in high-grade DCIS, which is much more readily recognized. It is the distinction of the overlapping features of UDH and low-grade DCIS which is much more problematic.

TABLE 9.12 Proposed Classifications for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Luminal spaces between the proliferating cells are irregular and often slitlike (Fig. 9.34). They are frequently concentrated around the periphery of the duct. Micropapillary projections, if present, are elongated (often tapering) or tuftlike and may resemble the pattern of hyperplasia seen in gynecomastia (60). The occasional presence of stromal cores results in true papillary structures. Islands of stroma, separated by a myoepithelial layer, may be seen within a solid proliferation of epithelium.

More importantly, cellular arrangement is also irregular. Nuclei are densely crowded, overlap, and appear to “touch.”

Necrosis and hemorrhage are rare, except in larger papillary lesions.

Periductal stromal changes, such as fibrosis, elastosis, and chronic inflammation, are uncommon.

Cell and nuclear size, shape, and placement vary. A polymorphic cell population consisting of epithelium and spindleshaped cells is present, sometimes with varying numbers of lymphocytes and histiocytes.

Apocrine metaplasia is often present. This is usually focal, but hyperplastic lesions composed entirely of apocrine cells also occur. As discussed previously, the cytologic appearance of apocrine cells may be worrisome, and a diagnosis of apocrine DCIS carcinoma should not be made without unequivocal evidence of malignancy.

The nuclei of proliferating cells are often parallel to one another, creating the impression of “streaming” (Fig. 9.35).

When epithelial bridges form, the nuclei of the proliferating cells lie parallel to the line of the bridge, and the bridges often taper in the center.

Nuclear features diagnostic of malignancy are absent. In particular, nucleoli are relatively inconspicuous, mitotic figures are infrequent, and abnormal mitotic figures are not seen.

of the number of ducts involved; if less than 2 mm in extent, the term atypical ductal hyperplasia was used. Follow-up data are consistent with the notion that minimal areas of DCIS, however defined, have the same prognosis as larger DCIS lesions.

oncoprotein production, suggests that biologic differences correlate with the histologic features (75).

TABLE 9.13 Van Nuys Prognostic Index for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

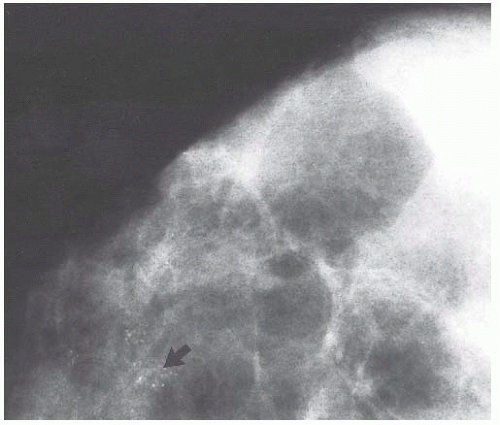

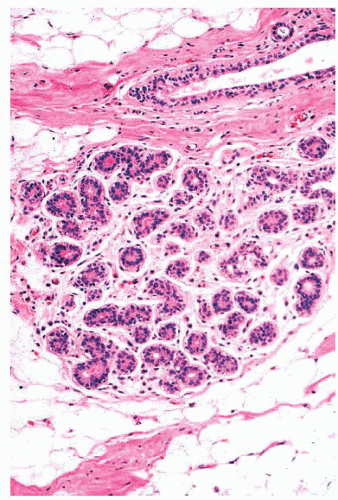

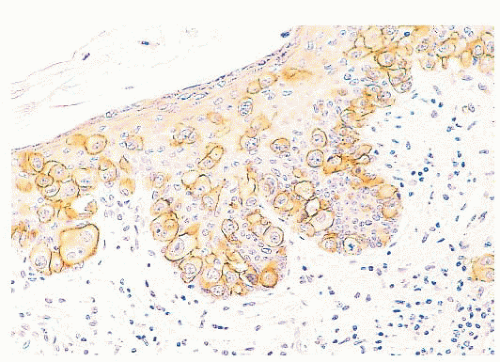

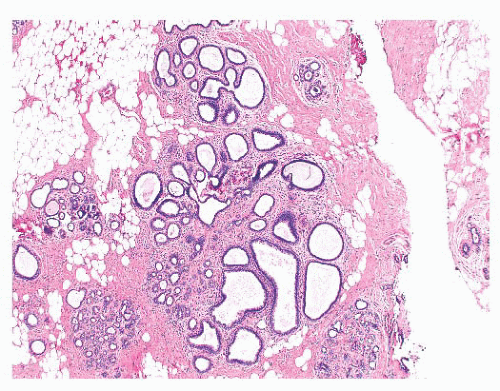

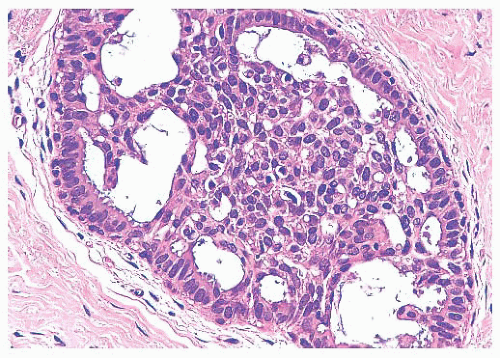

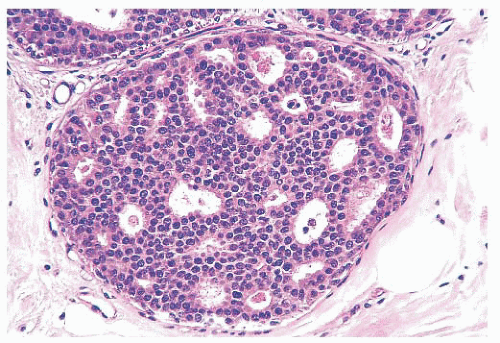

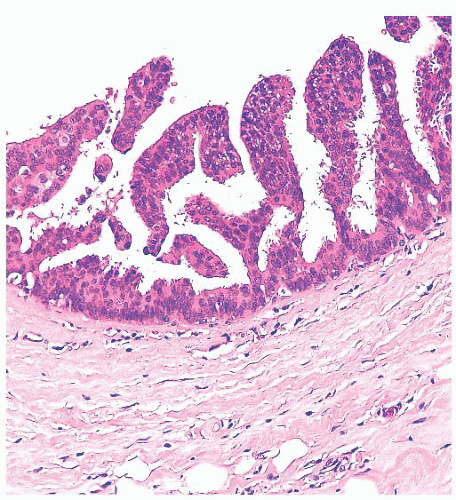

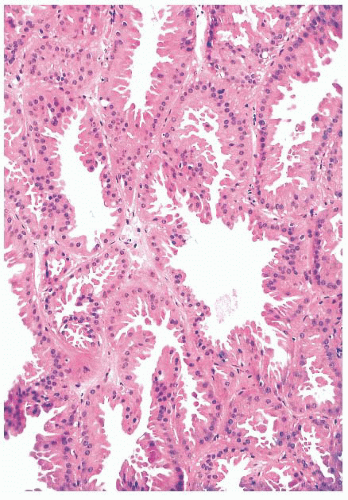

micropapillae. Small rosettes of cells with surface polarization, apparently separated from the papillae, are often seen floating free within the duct lumen. When the growth pattern is solid, a pattern of small, incompletely formed intercellular spaces with polarization of the surrounding cells usually results in a rosette-like appearance (Fig. 9.42). Necrosis is rarely associated with cells of low nuclear grade, and its absence is one of the defining features of some classifications, but the presence of small, focal areas of necrosis is allowed in others (Table 9.12). However, secretions are frequently seen within the duct lumen and should not be mistaken for necrosis. Calcification is not as frequent as in poorly differentiated DCIS and, when present, it is usually rounded and laminated or psammomatous and deposited within the secretions. Such calcification produces clusters of granular, sandlike particles on mammograms (Fig. 9.6), but this pattern is not as distinctive as that of the calcification seen in poorly differentiated, high-grade DCIS, in that similar patterns may also occur in benign lesions (70). Some patterns of well-differentiated DCIS are difficult to distinguish from lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Furthermore, some in situ carcinomas may show mixed ductal and lobular features.

spaces. In the first lesion, the cells lining the involved spaces have high-grade nuclei. In these cases, central necrosis may be evident, and such lesions are examples of poorly differentiated DCIS (80,81). Other lesions included in the category of clinging DCIS by some authorities (80,81) are composed of smaller, more uniform cells with low-grade nuclei, characteristic of well-differentiated DCIS. In many such lesions, the cells are columnar. Although lesions of this type are sometimes seen in conjunction with low-grade DCIS that has a cribriform or micropapillary pattern, they are being encountered with increasing frequency as isolated lesions in breast biopsy specimens obtained to assess mammographic microcalcifications. This pattern is not universally recognized as representing fully developed DCIS, and some consider it to be part of the spectrum of ADH (61,62) or columnar cell hyperplasia with atypia (45). Such lesions do not appear to be associated with as high a risk for breast cancer as fully developed forms of low-grade DCIS (81,82).

FIGURE 9.44 Ductal carcinoma in situ, apocrine type. The cells in this example of ductal carcinoma in situ possess abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. |

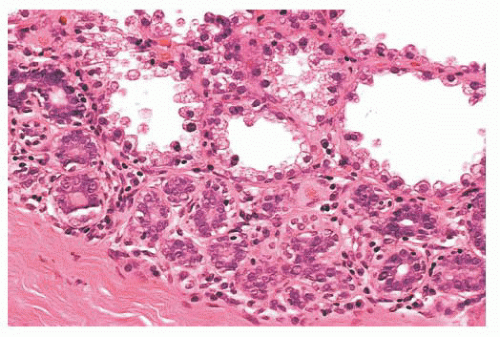

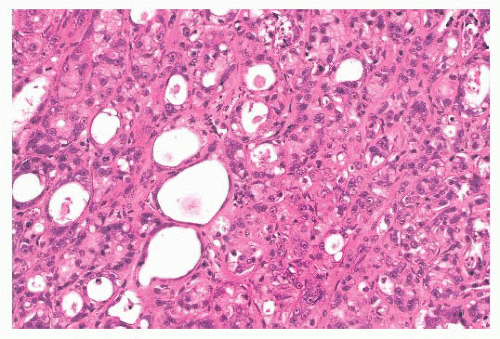

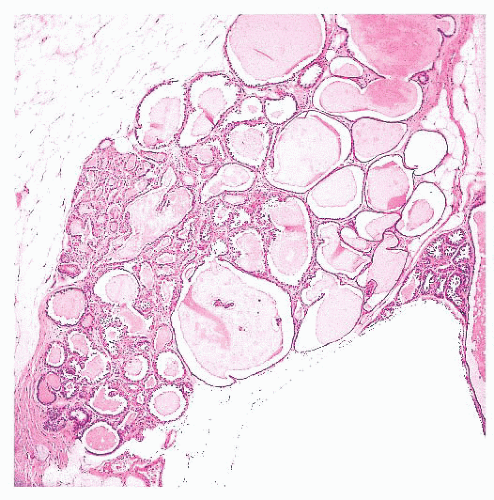

reminiscent of the lactating breast (Figs. 9.46 and 9.47). Stains for mucin show focal positivity within the epithelial cells; most of the cyst contents are negative. This lesion can easily be overlooked and should be borne in mind when apparently benign cysts are examined. Occasionally, hyperplasia is seen without fully developed carcinoma in situ. Such lesions are termed cystic hypersecretory hyperplasia (90).

help in evaluating possible foci of invasion. Small foci of invasion have been found more frequently in extensive DCIS lesions and in those of high nuclear grade (70,76). The presence of microinvasion—invasive foci less than 1 mm in diameter—has little effect on prognosis.

determination of the ER status of DCIS by immunohistochemistry is now being used with increasing frequency to guide patient management. At the present time, none of the other biologic markers has a clinical role.

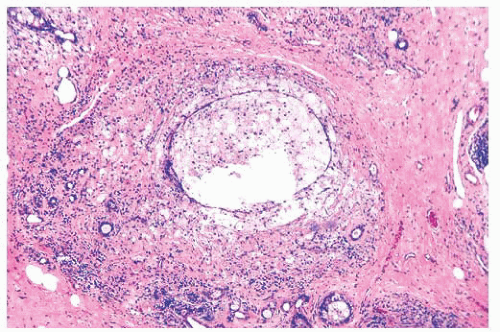

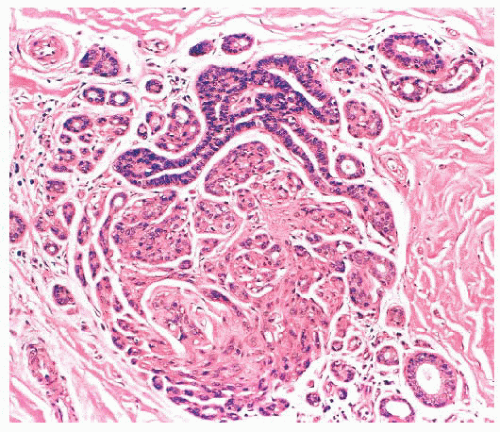

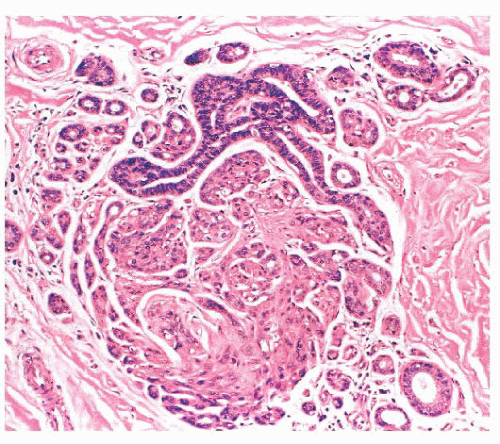

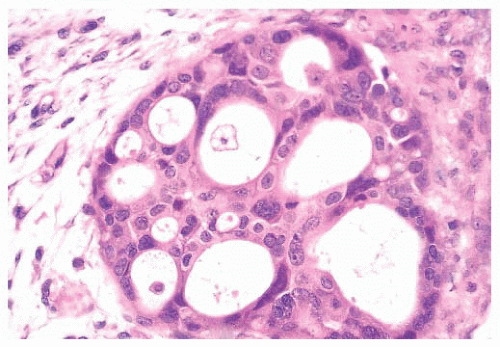

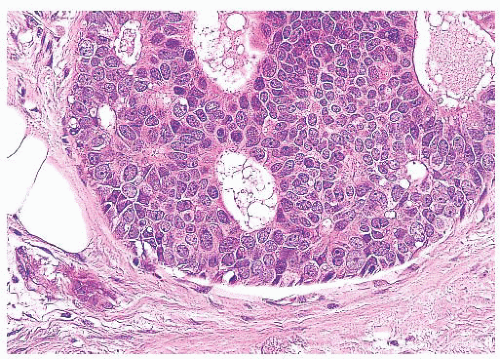

Benign papillomas have well-developed fibrovascular cores. In the classic form, these consist of arborescent fronds (Fig. 9.51), but often the papillae are broad and clublike, containing numerous components that result in a secondary adenomatous pattern.

TABLE 9.14 Papillary Lesions of the Breast (see text)

Papillomatosis

Variously used for diffuse proliferation in medium to small ducts, overlapping epitheliosis, UDH and florid ductal hyperplasia, or multiple papillomas

Juvenile papillomatosis

Multiple papillomas with cysts, often in young women

Papilloma

Localized tumor, grossly evident

Central/solitary

In large ducts, often subareolar

Peripheral/multiple

In smaller ducts to TDLU

Ductal adenoma

Sclerotic papilloma

Atypical

Variously contains ADH, DCIS

Papillary carcinoma

Encapsulated/intracystic

Often large, peripheral

Solid

Variant, often neuroendocrine

Infiltrating

Rare variant of invasive carcinoma

Micropapillary

Invasive carcinoma, often with lymphatic invasion

ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; TDLU, terminal duct lobular unit; UDH, usual ductal hyperplasia.

FIGURE 9.50 Gross photograph of a duct opened longitudinally to reveal a small fleshy papilloma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access