Neoplasm or not neoplasm: This hypercellular lesion is composed of pleomorphic cells with atypical nuclei, which

indicate neoplasm. If the lesion were not neoplastic, other etiologic categories, including infectious, inflammatory, toxic-metabolic, traumatic, vascular, developmental, and degenerative, would be considered.

TABLE 10.1 Indications for Intraoperative Consultation at Biopsy

Lesion requires proper surgical sampling of tissue for diagnosis and grading

Lesion may require special tissue processing

Culture for microorganisms

Fixation for electron microscopy

Fixation for immunohistochemistry

Touch preparation

Other special processing

Diagnosis affects immediate surgical procedure

TABLE 10.2 Surgery Directed Toward a Neurologic Symptom or Specific Disease

CONFIRMATORY FEATURES OF SUSPECTED DISEASE

Symptom/Suspected Disease

Structures

Reactant

Locationsa

Herpes simplex encephalitis

Encephalitis (Table 10.3), Cowdry A amphophilic nuclear inclusions of 90- to 100-nm “target” capsids

HSV antigen

Temporal or basilar frontal lobe, CNS; frequently bilateral

Toxoplasmosis

Necrosis containing 3- to 5-nm tachyzoites; (cysts); (inflammation)b

Toxoplasma antigen

CNS, frequent multiple lesions

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Demyelination, bizarre, glial, amphophilic nuclear inclusions of 15- to 25-nm or 30- to 40-nm diameter

JC/SV40 antigen, myelin, neurofilament

Cerebral white matter, CNS

Dementia/Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

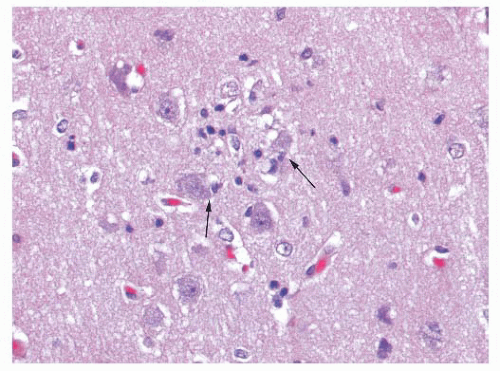

Cytoplasmic vacuoles indenting nuclei, gliosis (Table 10.3)

GFAP, prion (DANGER)

Bilateral cerebral cortex, gray matter

Small vessel disease

Vasculitis or arterial sclerosis or congophilic angiopathy

Amyloid, iron

Cerebrum, CNS; frequent multiple lesions

Dementia/Alzheimer disease

Argyrophilic plaques; neurofibrillary tangles of bihelical filaments

Neurofilament, tau

Bilateral cerebral cortex

Demyelination

Loss of myelin, gitter cells, with or without axonal preservation

Myelin, neurofilament

Cerebral white matter, CNS

Epilepsy

Low-grade glioma or ganglioglioma (Table 10.10), or gliosis (Tables 10.3 and 10.18), or vascular malformation

GFAP, neurofilament, synaptophysin, iron

Temporal lobe, cerebral cortex

a Most common or most specific location is listed first.

b Parentheses around a differential feature indicate an uncommon feature very useful in differential diagnosis when found.

CNS, central nervous system; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; HSV, herpes simplex virus; JC, JC virus; SV, simian virus.

TABLE 10.3 Differential Features of Cells Infiltrating Central Nervous Parenchyma

DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES

Diagnosis

Structures

Reactant

Locationsa

Gliosisb

Cells are fibrillar, uncrowded; round or oval nuclei

GFAP in glial filament

CNS

Macrophages

Cells and nuclei are round to elongated; cell content reflects injury

CD68; α-ACT

CNS, meninges

Encephalitis and/or cerebritis

Perivascular mixture of inflammatory cells

CD3, CD20, LCA, κ and λ Ig, α-ACT; CD68, microorganism

CNS gray matter, CNS

Hemorrhage

Red blood cells or macrophages with hemosiderin

Fibrin, iron

Deep cerebrum, cerebellum, CNS

Margin of gliomasc

Cells are fibrillar; angular nuclei indent each other; (mitoses)c,d

GFAP

CNS

Lymphoma

Perivascular, noncohesive small, round cells

CD3, CD20, LCA, κ and λ Ig

Deep cerebrum, CNS; meninges

a Most common or most specific location is listed first.

b Nonspecific reaction to injury.

c Suspicion of margin of glioma on frozen section should be followed by a request for another more central biopsy. Mitoses suggest margin of a high-grade glioma.

d Parentheses around a differential feature indicate an uncommon feature that is very useful in differential diagnosis when it is found.

α-ACT, α-antichymotrypsin macrophage marker; CNS, central nervous system; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; Ig, immunoglobulin; LCA, leukocyte common antigen (CD45/CD45RB).

TABLE 10.4 Viral Inclusions in the Central Nervous System

Nucleus

Cytoplasm

Neurons

Herpes simplex and zoster

+

−

Rabies

−

+

SSPE (measles)

+

−

Oligodendrocytes

PML (JC virus)

+

−

SSPE (measles)

+

−

Various cells (endothelial, ependymal, glial)

Cytomegalovirus

+

+

PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; SSPE, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

TABLE 10.5 Causes to Consider in Intracranial Hematoma

Traumatic

Cerebral contusion

Epidural or subdural hematoma

Infectious and inflammatory

Vasculitis

Fungus (mycotic aneurysm)

Developmental vascular

Vascular malformation (arteriovenous malformation, cavernous angioma)

Aneurysm

Hematologic

Thrombocytopenia

Sickle cell anemia

Neoplastic

Primary (high-grade glioma)

Metastatic (e.g., melanoma, renal cell carcinoma)

Leukemia (chloroma in acute myelogenous leukemia)

Vascular

Amyloid angiopathy

Hypertension

Conversion of ischemic infarct

Toxic-metabolic: anticoagulation related

TABLE 10.6 Vascular Malformations

Malformationa

Vessels

Neuropil

Gliosis and Hemosiderin-Laden Macrophages

Arteriovenous malformation

Arteries, veins, arterialized veins

Absent, except around feeding vessels

Presentb

Cavernous angioma

Compact cluster thin-walled to thickwalled vessels, mineralization

Absent usually

Presentb

Capillary telangiectasia

Capillaries, thin-walled

Admixed

Absent

Venous malformation

Veins, often dilated

Admixed

Absent

Varix

Vein, dilated (vein of Galen)

Absent

Absent unless ruptured

a Location: Each can be found anywhere in the central nervous system; capillary telangiectasias often in brainstem and venous malformations in the spinal leptomeninges.

b Gliosis and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are consistent with leakage; they serve as a seizure focus, and they signal a tendency for spontaneous hemorrhage.

TABLE 10.7 Relative Frequency of Most Common Pediatric and Adult Brain Neoplasms

CHILDREN

ADULTS

Location

Diagnosis and Frequency

Location

Diagnosis and Frequency

Anterior fossa

Miscellaneous

33%

Anterior fossa

Gliomas (cerebrum)a

33%

Meningiomas (dura)

13%

Metastases (cerebrum)

12%

Pituitary adenomas (sella)

5%

Miscellaneous

4%

Total

67%

Posterior fossa

Astrocytomas (cerebellum)a

26%

Medulloblastomas (cerebellum)

24%

Ependymomas (fourth ventricle)

14%

Posterior fossa

Schwannomas (eighth cranial nerve)

8%

Miscellaneous

3%

Miscellaneous

25%

Total

67%

Total

33%

a Most common site in parentheses. See entry in text for other locations.

TABLE 10.8 World Health Organization Criteria for Grading of Astrocytomas

Grade

Nomenclature

Histologic Features

1

Pilocytic

Circumscribed; biphasic: bipolar piloid cells and multipolar cells; microcysts, Rosenthal fibers, and granular bodies; may or may not have rare mitotic figures, vascular proliferation, or focal necrosis

2

Diffuse

Moderate hypercellularity of monotonous cells; mild nuclear atypia; no or minimal mitotic activity

3

Anaplastic

Increased cellularity and diffuse infiltration; increased nuclear atypia; increased mitotic activity

4

Glioblastoma

Vascular proliferation or necrosis; crowded anaplastic cells; marked nuclear atypia; brisk mitotic activity

From Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Nervous System. Geneva: IARC Press, 2007, with permission.

Primary or metastatic: These cells are fibrillar. They are plump and large but not spindled or vacuolated. The neoplastic cell nuclei are moderately pleomorphic; the cells have small processes emanating from them. The lesion lacks rosettes. There is a vessel cuffed by many small, reactive-appearing mononuclear cells. No epithelial elements are recognized. The findings are those of a primary CNS neoplasm rather than a metastatic lesion (Tables 10.10 and 10.11).

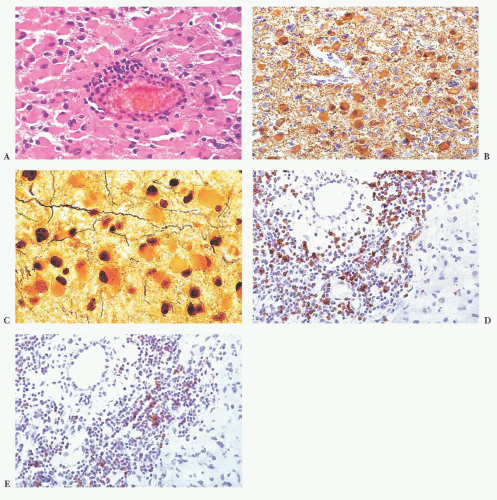

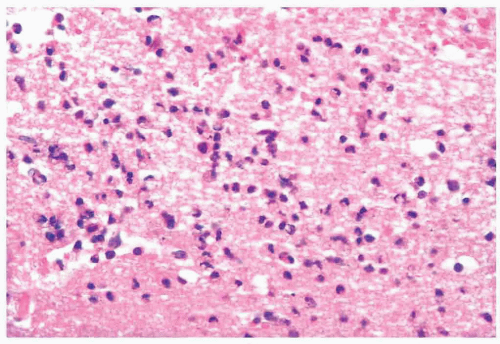

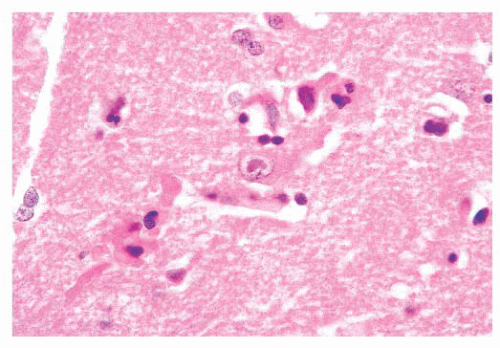

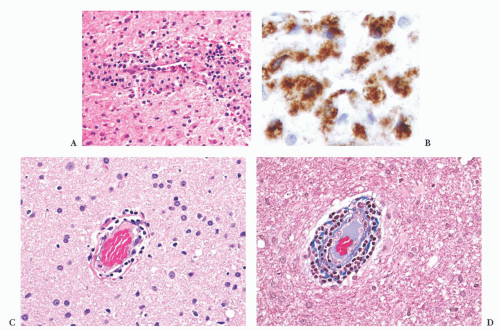

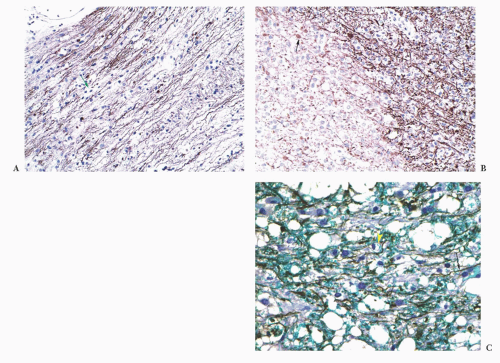

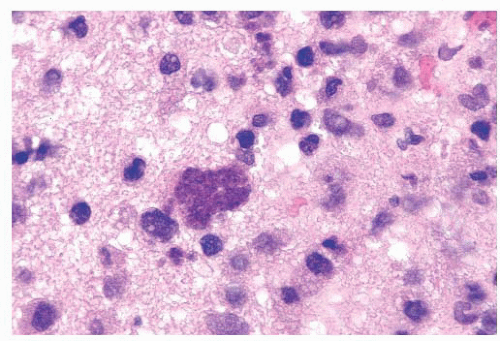

Glial, neuronal, and other primary considerations: Possible primary CNS neoplasm diagnoses in Table 10.10 include giant cell astrocytoma, gemistocytic astrocytoma, ganglion cell tumor, or histiocytosis (Fig. 10.1). Although nuclei of the lesional cells have a slight resemblance to neuronal nuclei, their chromatin is more condensed. Their cytoplasm is pink without purple Nissl substance of neurons. Bielschowsky stain shows no silver staining of neoplastic cells (Fig. 10.1); neoplastic cells were also negative for synaptophysin, a neuronal marker (not shown). Aggregate features do not support a ganglion cell tumor. The neoplastic cells are positive for the intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker that accentuates their fibrillarity and confirms their astrocytic nature (Fig. 10.1). The related text in this chapter describes differences between gemistocytic astrocytoma and giant cell astrocytoma. Gemistocytic astrocytomas resemble reactive astrocytes and have abundant, plump, hyaline cytoplasm and peripheralized nuclei. Macrophages (histiocytes) are GFAP-negative and lack the fibrillary structure highlighted by GFAP, arguing against the diagnosis histiocytosis. Neoplastic cells are negative for the T-lymphocyte marker CD45RO (Fig. 10.1D) and the B-lymphocyte marker CD20 (Fig. 10.1E), whereas polyclonal perivascular lymphocytes are positive. Therefore, the aggregate histologic, histochemical, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) findings support the diagnosis of gemistocytic astrocytoma.

TABLE 10.9 World Health Organization Criteria for Grading of Oligodendrogliomas

Grade

Nomenclature

Histologic Features

2

Oligodendroglioma

Moderate cellularity; homogeneously round nuclei, “fried egg” halo (paraffin); fine capillary network; mineralization (microcalcifications)

3

Anaplastic oligodendroglioma

Increased cellularity; high mitotic rate; marked cytologic atypia; microvascular proliferation; necrosis

From Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Nervous System. Geneva: IARC Press, 2007, with permission.

Grade of astrocytoma: Bielschowsky stain reveals passing axons of brain tissue infiltrated by this neoplasm (Fig. 10.1). Infiltration of brain tissue is seen in astrocytomas of grade II to IV. Grade III astrocytomas have mitotic activity, but there is no evidence of mitotic activity. Features of grade IV, microvascular proliferation and necrosis, are absent. This astrocytoma is grade II. Most gemistocytic astrocytomas are grade II, although they tend to progress to a higher grade. Grading is further discussed in the “Gemistocytic Astrocytoma,” “Diffuse Astrocytoma,” and “Anaplastic Astrocytoma” sections. Other algorithmic approaches to the brain biopsy are available (9,10).

Knowledge about past medical history (e.g., previous CNS or primary neoplasms, connective tissue disease, immunosuppressive disease) is critical to interpretation. Likewise, knowledge about preoperative therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, radiosurgery) is also critical to interpretation of findings (e.g., necrosis, vascular fibrosis).

TABLE 10.10 Differential Diagnosis of a Mass of Fibrillar Cells | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 10.11 Differential Diagnosis of a Mass of Epithelioid Cells | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

viewing a gross specimen. The neurosurgical lesions summarized in Tables 10.610.7,10.8,10.9,10.10,10.11,10.12,10.13,10.14,10.15,10.16,10.17,10.18 and 10.19 are usually focal, whereas the lesions in the biopsies directed toward a neurologic disease tend to be more diffuse (Table 10.2). One particularly problematic diagnosis is vasculitis, which can be focal, multifocal, or diffuse. If you are lucky enough to be consulted on any multifocal case, advise the surgeon to target a new or subacute radiographic lesion.

TABLE 10.12 Differential Diagnosis of a Mass of Conspicuously Different Cells | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

of everyone’s time. It is a ritual that helps the clinician say that everything was tried on a moribund patient.

TABLE 10.13 Differential Diagnosis of a Mass of Small Blue Cell Tumor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 10.14 Differential Diagnosis of a Mass That Includes Syncytial Cells | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 10.15 World Health Organization Criteria for Grading of Meningiomasa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 10.16 Histiocytoses Affecting the Central Nervous System Compared with Macrophages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 10.17 Carcinomas and Melanoma Metastatic to Brain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 10.18 Differential Diagnosis of Cyst with Wall of Fibrillar Cells | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 10.19 Differential Diagnosis of a Cyst with Wall Lined by Epithelium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

definitively and grade every case but, rather, (a) to ensure that lesional tissue has been obtained for subsequent diagnosis and grading, (b) to ensure the lesional tissue has been appropriately sampled (e.g., that high-grade features are noted on a suspected glioblastoma based on imaging features), (c) to provide sufficient preliminary diagnostic information to optimize surgery, and (d) to perform appropriate special tissue processing (Table 10.1). Optimizing surgery depends on the individual case and on whether open biopsy or stereotactic needle biopsy is being done (see later sections).

TABLE 10.20 Inclusion Immunophenotype | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 10.21 Findings in Surgically Resected Temporal Lobes in Setting of Seizure Disorder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History: Patient age, duration of symptoms, and surgical location are the minimum.

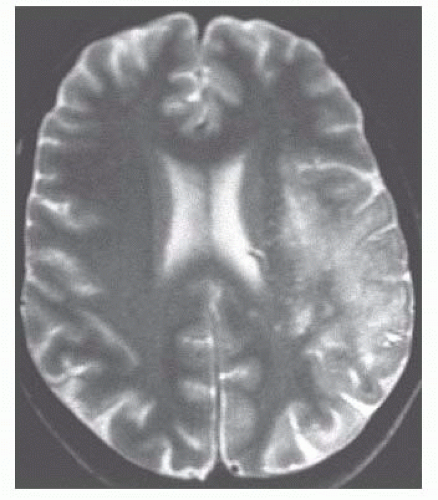

Radiography: View images and/or read reports. On reports, objective findings trump interpretation. Are there one or more masses? Infiltrative? Enhancing?

Check for prior specimens: Slides and reports.

Cell type: Fibrillar, epithelioid, mixed, small and crowded, or syncytial (e.g., fibrillar*)

Major features: Such as mass; marked cellular and nuclear pleomorphism*

Differential (Dif): Such as glioblastoma (GbM), giant cell astrocytoma (GCA), pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA), sarcoma (Src), or melanoma (Mel)*

Location: Entirely extramedullary (e.g., outside of CNS [excludes GbM, GCA]), skull invasion (favors Src, Mel), subependymal (favors GCA)

Radiography: Diffuse margin with CNS (favors GbM)

Duration of symptoms: For a new mass, less than 3 months favors GbM, Src, Mel

Microscopic features:

No mitoses (favors GCA, PXA)

Granular bodies (favors PXA)

Necrosis (favors GbM, Src, Mel)

Microvascular proliferation (favors GbM)

Intercellular collagen (favors PXA, Src)

a diagnosis or monitor consequences of therapy. Biopsies can be performed using CT- or MRI-guided stereotactic needle biopsy or using an open technique. Therapeutic resections attempt gross total excision of lesional tissue. Individual cases may combine more than one procedure at a single operation. For example, open biopsy for diagnosis of an intramedullary spinal cord tumor may proceed directly to a therapeutic resection if the intraoperative evaluation suggests ependymoma.

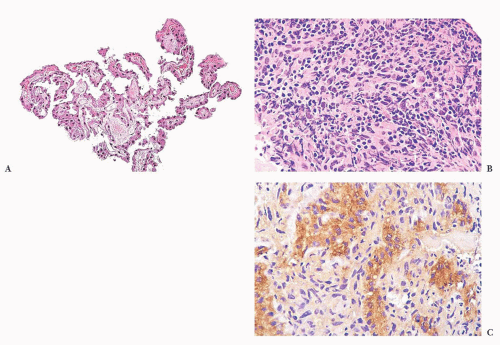

of tissue, with a comment about the need for neuroanatomical and clinical correlation to rule out the possibility of normal structure. Stereotactic biopsies of pineal tumors present problems analogous to the problems the fabled elephant presented to the six blind men (Fig. 10.2).

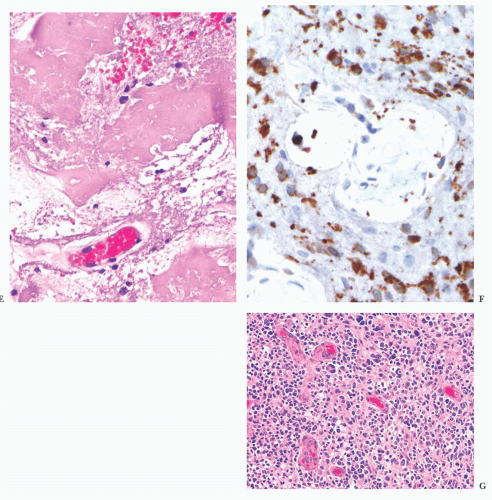

walls. Radiation necrosis is not pseudopalisading, and during its maturation, it shows tiny flecks of calcification. Both the tumor and white matter are particularly sensitive to radiation, grey matter being more resistant. Mitoses and tumor cell density are decreased with TE.

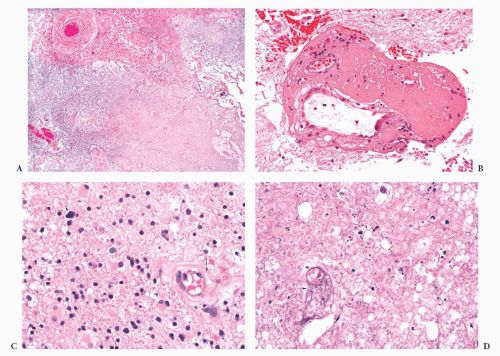

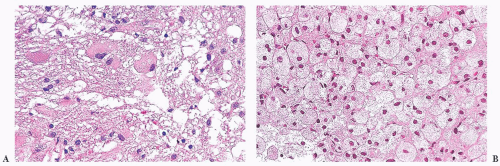

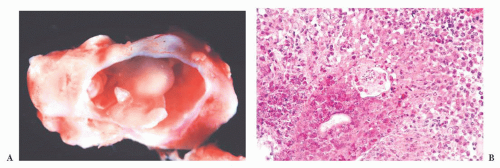

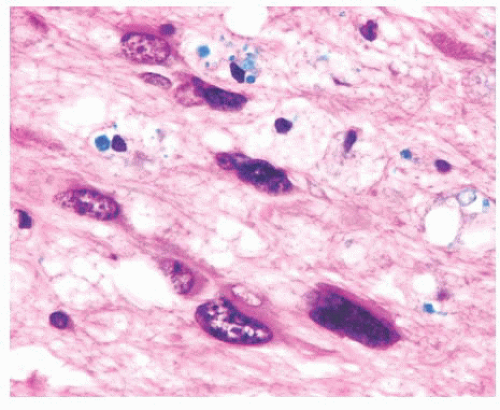

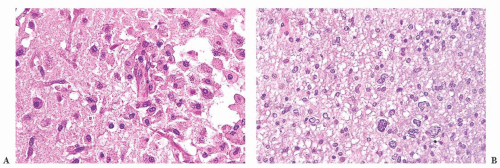

FIGURE 10.4 This frontal lobe specimen resected 24 days after an initial biopsy simulates an organizing infarct (A). The original biopsy revealed an obvious glioma (B). |

Squash/smear/touch preparations

Unfrozen routine permanent paraffin sections

Frozen sections

Electron microscopy (EM) (retain a small portion in a fixative for EM, if necessary)

Frozen tissue, for possible future molecular diagnostic studies (freeze fresh tissue as soon as possible and store)

Other (microbiology, flow cytometry, cytogenetics, molecular diagnostics)

Cassettes should be labeled with pencil as formic acid will dissolve away even the ink specially formulated for histologic processing.

Normal plastic cassettes are resistant to formic acid, but the thin plastic netting of cassettes designed for small biopsies will dissolve in formic acid, so a small biopsy should be wrapped in lens paper to keep it in the cassette. Metal tops should not be used.

features are emphasized in the following sections, under each entity. Depending on difficulty, the differential can be solved on H&E or IHC (18).

inflammatory, necrotic, traumatic, degenerative, and neoplastic processes (21,22 and 23). The origin of these cells is variable among lesions and consists of some combination of (a) “native” parenchymal microglial cells, which can proliferate along with (b) blood-derived macrophages entering the brain parenchyma in response to damage (22). The fate of the latter cells may be to remain at the site of injury or migrate to the perivascular space (23). Because distinction among these origins is not useful diagnostically, the inclusive term macrophages can be employed.

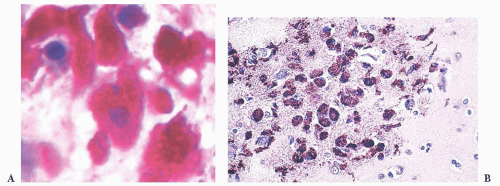

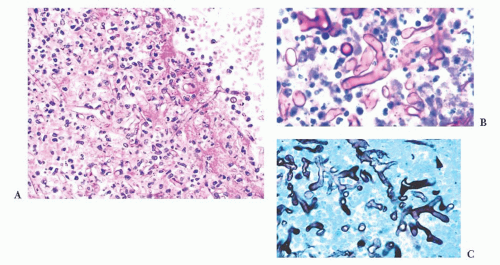

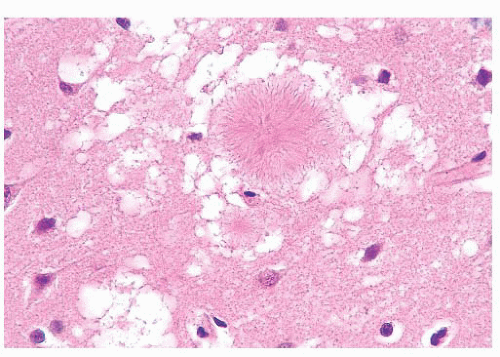

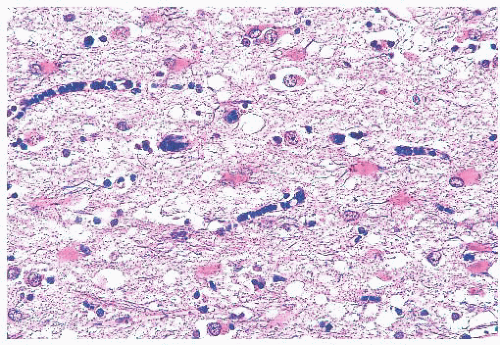

FIGURE 10.6 (A) Perivascular mixed inflammatory infiltrate is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages around but not within vessel walls. (B) Chronic encephalitis stained with CD68 shows elongated microglial macrophages within brain tissue and around vessels but not within the vascular wall. Note the normal thin endothelial lining (compare with vasculitis, Fig. 10.25C,D). |

wounds and implants (24). Macrophages ingest the irritant or injured cellular constituents and move them to the perivascular space (23). In the absence of classic lymph nodes in the brain, this perivascular region is where cells that respond to antigens intermingle. Depending on severity and duration of illness, the perivascular inflammation varies substantially. Old hemorrhage is characterized mainly by perivascular macrophages laden with hemosiderin. Viral or autoimmune encephalitis produces a maximal response, with abundant perivascular macrophages and lymphocytes along with parenchymal infiltrates of microglial cells and microglial nodules.

modalities of variable severity. The etiology is often elusive, but etiologies include infectious (herpes simplex virus [HSV], CMV, etc.), inflammatory (multiple sclerosis [MS], connective tissue disease, etc.), vascular (infarct due to thrombosis), developmental (vascular malformation), traumatic, and iatrogenic processes (29,30). Workup is based on imaging and CSF and serum evaluation; biopsy is occasionally performed to search for an etiology.

(e.g., from a primary pulmonary source) or via direct extension from an infected sinus.

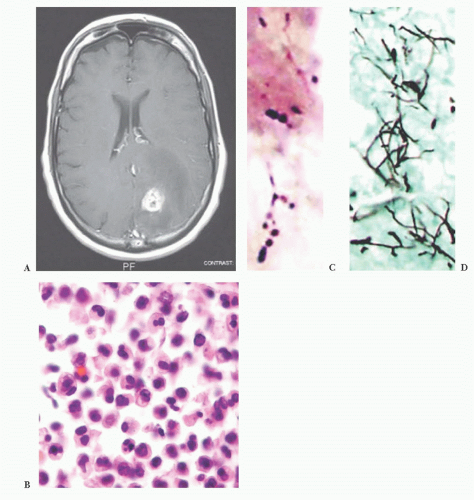

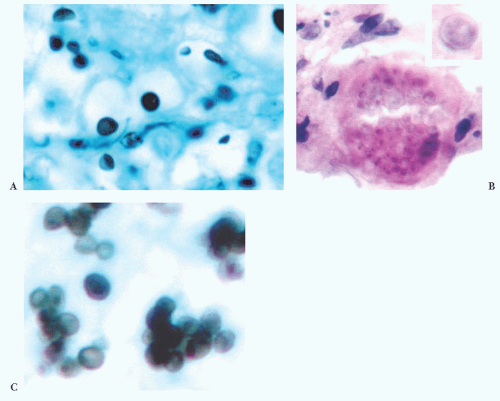

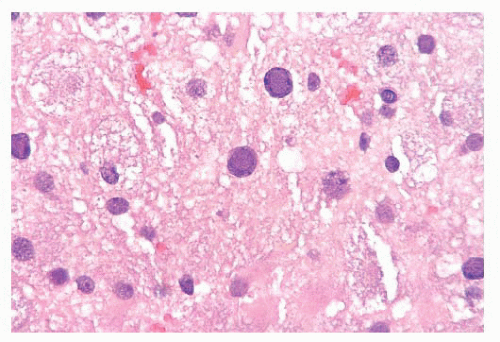

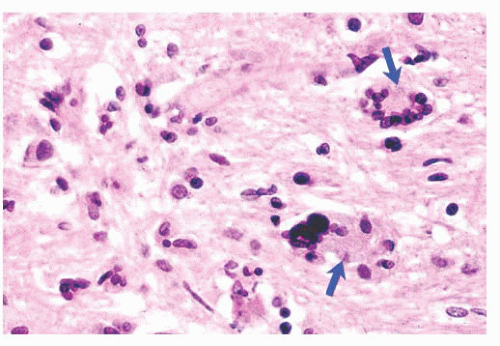

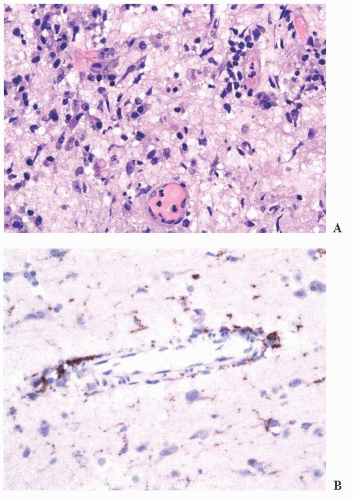

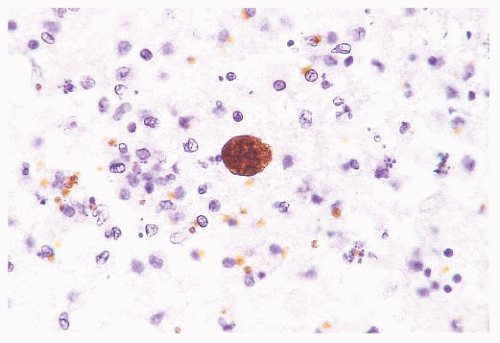

FIGURE 10.12 Toxoplasmosis in an immunodeficient patient. Amphophilic pseudocyst full of a cluster of bradyzoites is irregular and larger than surrounding cells. |

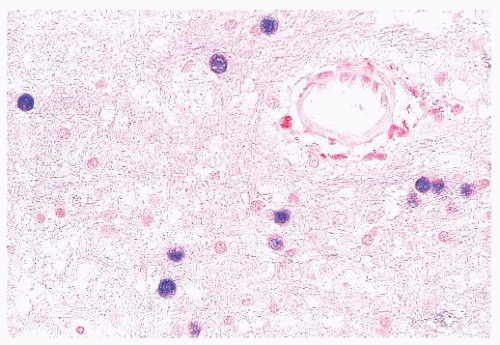

FIGURE 10.13 Cyst and free tachyzoites immunostained for Toxoplasma antigen (immunoperoxidase with hematoxylin counterstain). |

IgG and IgM in both the CSF and serum. Brain biopsy is rarely performed. When undertaken, viral encephalitis-type changes predominate and there is loss of myelin in subcortical white matter (28). Nuclear inclusions may be detected in neurons and oligodendroglial cells by H&E. IHC or ISH evaluation detects measles virus antigen.

produce vacuoles that encircle neurons, vessels, and glia; these are larger than CJD vacuoles. Nonetheless, because many vacuoles are not related to prions, molecular diagnosis of prions is needed to confirm suspicions based on vacuoles.

fraction of axons are lost in chronic MS. In contrast, axonal loss precedes myelin loss in an infarct (Fig. 10.26). The amount of gliosis increases with the chronicity of the lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree