Chapter 16 Bereavement

Bereavement as loss

Every change involves loss and gain: arriving; departing; growing; declining; achieving; failing.

The old environment must be given up, the new accepted (Murray-Parkes, 1986: 30).

The grief process

Grief is a process with successive stages, the progression of which is not strictly linear: often a stage will be repeated and emotions apparently dealt with may be rehearsed again. Murray-Parkes (1986) speaks of five stages: alarm – searching – mitigation – anger and guilt – gaining a new identity. Ainsworth-Smith et al. (1988) identifies three stages: shock and disbelief – awareness – resolution. Bradley (1990) speaks of: numbness – pining – depression – recovery.

Shock

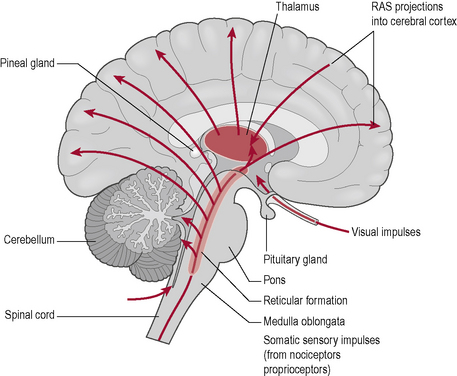

Shock following bereavement is controlled by the reticular activating system (Fig. 16.1). The reticular formation, a part of it, is a complex neural network in the central core of the brainstem which passes nerve impulses between the brain and the spinal cord, monitoring the state of the body’s behaviour and alertness (see Wikipedia). It has a vast number of synaptic links with other parts of the brain that constantly receive ‘information’, transmitted in ascending and descending tracts (Wilson 1994 p. 253). One of its functions is to pass (or block) selective information to the cerebral cortex. Stimulation of the reticular formation has been shown to produce first, curiosity, then successively (as the intensity of stimulation increases) attention, fear and panic (Murray-Parkes 1986 p. 51). It is because of this that:

• people who are in shock can do strange things that are out of character for them

• sleep patterns, appetite and control of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are often disturbed.

Anger and remorse

• anger directed against the person who has died: How could they do this to me? This sort of anger is more often thought than expressed: it is an emotive rather than a properly emotional response, not based on reason – and is unsustainable. It is easier to accept when there is a ‘reason’ to justify anger, for example if a person has been unreasonable, or there are debts. But someone who gets angry simply because they have been left alone, because they have been bereaved, can become very guilty about what appears to be self-indulgence.

• deflected anger: although many experience anger because the situation is not what they would have wanted (we would rather not have experienced loss), it becomes focused on the nearest available target. Doctors are not uncommon targets after a long illness: relatives sometimes find it hard to believe that there really was nothing that could have been done.

• frustration can be expressed as anger. Death is so absolute and immutable. Frustration (and subsequent anger) grows out of a sense of hopelessness and the inability to ‘make things better.’ Loss cannot be prevented, nor our reaction to it.

To help relieve these situations with essential oils, see below.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree