Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Although symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is rare in men younger than 50 years of age, it is very common in men 60 years and older because of androgen-driven growth in the size of the prostate. Symptoms commonly result from both static and dynamic factors.

Although symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is rare in men younger than 50 years of age, it is very common in men 60 years and older because of androgen-driven growth in the size of the prostate. Symptoms commonly result from both static and dynamic factors.

![]() BPH symptoms may be exacerbated by medications, including antihistamines, phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, and anticholinergic agents. In these cases, discontinuing the causative agent can relieve symptoms.

BPH symptoms may be exacerbated by medications, including antihistamines, phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, and anticholinergic agents. In these cases, discontinuing the causative agent can relieve symptoms.

![]() Specific treatments for BPH include watchful waiting, drug therapy, and surgery.

Specific treatments for BPH include watchful waiting, drug therapy, and surgery.

![]() For patients with mild disease who are asymptomatic or have mildly bothersome symptoms and no complications of BPH disease, no specific treatment is indicated. These patients can be managed with watchful waiting. Watchful waiting includes behavior modification and return visits to the physician at 6- or 12-month intervals for assessment of worsening symptoms or signs of BPH.

For patients with mild disease who are asymptomatic or have mildly bothersome symptoms and no complications of BPH disease, no specific treatment is indicated. These patients can be managed with watchful waiting. Watchful waiting includes behavior modification and return visits to the physician at 6- or 12-month intervals for assessment of worsening symptoms or signs of BPH.

![]() If symptoms progress to a moderate or severe level, drug therapy or surgery is indicated. Drug therapy with an α1-adrenergic antagonist is an interim measure that relieves voiding symptoms. In select patients with prostates of at least 40 g, 5α-reductase inhibitors delay symptom progression and reduce the incidence of BPH-related complications.

If symptoms progress to a moderate or severe level, drug therapy or surgery is indicated. Drug therapy with an α1-adrenergic antagonist is an interim measure that relieves voiding symptoms. In select patients with prostates of at least 40 g, 5α-reductase inhibitors delay symptom progression and reduce the incidence of BPH-related complications.

![]() All α1-adrenergic antagonists are equally effective in relieving BPH symptoms, but do not halt disease progression or delay surgical intervention. Older second-generation immediate-release formulations of α1-adrenergic antagonists (e.g., terazosin, doxazosin) can cause adverse cardiovascular effects, mainly first-dose syncope, orthostatic hypotension, and dizziness. For patients who cannot tolerate hypotensive effects of the second-generation agents, the third-generation, pharmacologically uroselective agents (e.g., tamsulosin, silodosin) are good alternatives. An extended-release formulation of alfuzosin, a second-generation, functionally uroselective agent, and third-generation pharmacologically uroselective agents have fewer cardiovascular adverse effects than immediate-release formulations of terazosin or doxazosin. Generic formulations are less expensive than single-source agents and should be preferentially prescribed in patients with limited financial resources.

All α1-adrenergic antagonists are equally effective in relieving BPH symptoms, but do not halt disease progression or delay surgical intervention. Older second-generation immediate-release formulations of α1-adrenergic antagonists (e.g., terazosin, doxazosin) can cause adverse cardiovascular effects, mainly first-dose syncope, orthostatic hypotension, and dizziness. For patients who cannot tolerate hypotensive effects of the second-generation agents, the third-generation, pharmacologically uroselective agents (e.g., tamsulosin, silodosin) are good alternatives. An extended-release formulation of alfuzosin, a second-generation, functionally uroselective agent, and third-generation pharmacologically uroselective agents have fewer cardiovascular adverse effects than immediate-release formulations of terazosin or doxazosin. Generic formulations are less expensive than single-source agents and should be preferentially prescribed in patients with limited financial resources.

![]() 5α-Reductase inhibitors are useful primarily for patients with large prostates greater than 40 g who wish to avoid surgery and cannot tolerate the side effects of α1-adrenergic antagonists. 5α-Reductase inhibitors have a slow onset of action, taking up to 6 months to exert maximal clinical effects, which is a disadvantage of their use. In addition, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculation disorders are common adverse effects, which may be troublesome problems in sexually active patients.

5α-Reductase inhibitors are useful primarily for patients with large prostates greater than 40 g who wish to avoid surgery and cannot tolerate the side effects of α1-adrenergic antagonists. 5α-Reductase inhibitors have a slow onset of action, taking up to 6 months to exert maximal clinical effects, which is a disadvantage of their use. In addition, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculation disorders are common adverse effects, which may be troublesome problems in sexually active patients.

![]() Phosphodiesterase inhibitors are indicated in patients with moderate-severe BPH and erectile dysfunction. They improve lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), but do not increase urinary flow rate or reduce postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume. For these reasons, phosphodiesterase monotherapy is considered less effective than an α-adrenergic antagonist for BPH. A phosphodiesterase inhibitor may be used alone or along with an α-adrenergic antagonist.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors are indicated in patients with moderate-severe BPH and erectile dysfunction. They improve lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), but do not increase urinary flow rate or reduce postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume. For these reasons, phosphodiesterase monotherapy is considered less effective than an α-adrenergic antagonist for BPH. A phosphodiesterase inhibitor may be used alone or along with an α-adrenergic antagonist.

![]() Anticholinergic agents are indicated in patients with moderate to severe LUTS with a predominance of irritative voiding symptoms. Because older patients are at high risk of systemic anticholinergic adverse effects, uroselective anticholinergic agents may be preferentially prescribed. To minimize the risk of acute urinary retention, a patient’s PVR urine volume should be less than 250 mL before initiating treatment with an anticholinergic agent.

Anticholinergic agents are indicated in patients with moderate to severe LUTS with a predominance of irritative voiding symptoms. Because older patients are at high risk of systemic anticholinergic adverse effects, uroselective anticholinergic agents may be preferentially prescribed. To minimize the risk of acute urinary retention, a patient’s PVR urine volume should be less than 250 mL before initiating treatment with an anticholinergic agent.

![]() Surgery is indicated for moderate to severe symptoms of BPH for patients who do not respond to or do not tolerate drug therapy or for patients with complications of BPH. It is the most effective mode of treatment in that it relieves symptoms in the greatest number of men with BPH. However, the two most widely used techniques, transurethral resection of the prostate and open prostatectomy, are associated with the highest rates of complications, including retrograde ejaculation and erectile dysfunction. Therefore, minimally invasive surgical procedures are often desired by patients. These relieve symptoms and are associated with a lower rate of adverse effects, but they have higher reoperation rates than the gold standard procedures.

Surgery is indicated for moderate to severe symptoms of BPH for patients who do not respond to or do not tolerate drug therapy or for patients with complications of BPH. It is the most effective mode of treatment in that it relieves symptoms in the greatest number of men with BPH. However, the two most widely used techniques, transurethral resection of the prostate and open prostatectomy, are associated with the highest rates of complications, including retrograde ejaculation and erectile dysfunction. Therefore, minimally invasive surgical procedures are often desired by patients. These relieve symptoms and are associated with a lower rate of adverse effects, but they have higher reoperation rates than the gold standard procedures.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common benign neoplasm of American men. A nearly ubiquitous condition among elderly men, BPH is of major societal concern, given the large number of men affected, the progressive nature of the condition, and the healthcare costs associated with it.

This chapter discusses BPH and its available treatments: watchful waiting, α1-adrenergic antagonists, 5α-reductase inhibitors, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, anticholinergic agents, and surgery. The limitations of phytotherapy are described.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

![]() According to the results of autopsy studies, approximately 80% of elderly men develop microscopic evidence of BPH. About half of the patients with microscopic changes develop an enlarged prostate gland, and as a result, they develop symptoms including difficulty emptying urine from the urinary bladder. Approximately half of symptomatic patients eventually require treatment.

According to the results of autopsy studies, approximately 80% of elderly men develop microscopic evidence of BPH. About half of the patients with microscopic changes develop an enlarged prostate gland, and as a result, they develop symptoms including difficulty emptying urine from the urinary bladder. Approximately half of symptomatic patients eventually require treatment.

The peak incidence of clinical BPH occurs at 63 to 65 years of age. Symptomatic disease is uncommon in men younger than 50 years, but some urinary voiding symptoms are present by the time men turn 60 years of age. The Boston Area Normative Aging Study estimated that the cumulative incidence of clinical BPH was 78% for patients at age 80 years.1 Similarly, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging projected that approximately 60% of men at least 60 years old develop clinical BPH.2

NORMAL PROSTATE PHYSIOLOGY

Located anterior to the rectum, the prostate is a small heart-shaped, chestnut-sized gland located below the urinary bladder. It surrounds the proximal urethra like a doughnut.

Soft, symmetric, and mobile on palpation, a normal prostate gland in an adult man weighs 15 to 20 g. Physical examination of the prostate must be done by digital rectal examination (i.e., the prostate is manually palpated by inserting a finger into the rectum). Thus, the prostate is examined through the rectal mucosa.

The prostate has two major functions: (a) to secrete fluids that make up a portion (20–40%) of the ejaculate volume and (b) to provide secretions with antibacterial effect possibly related to its high concentration of zinc.2

At birth, the prostate is the size of a pea and weighs approximately 1 g. The prostate remains that size until the boy reaches puberty. At that time, the prostate undergoes its first growth spurt, growing to its normal adult size of 15 to 20 g by the time the young man is 25 to 30 years of age. The prostate remains this size until the patient reaches age 40 years, when a second growth spurt begins and continues for the rest of his lifetime. During this period, the prostate can quadruple in size or grow even larger.

The prostate gland comprises three types of tissue: epithelial tissue, stromal tissue, and the capsule. Epithelial tissue, also known as glandular tissue, produces prostatic secretions. These secretions are delivered into the urethra during ejaculation and contribute to the total ejaculate volume. Androgens stimulate epithelial tissue growth. Stromal tissue, also known as smooth muscle tissue, is embedded with α1-adrenergic receptors. Stimulation of these receptors by norepinephrine causes smooth muscle contraction, which results in an extrinsic compression of the urethra, reduction of the urethral lumen, and decreased urinary bladder emptying. The normal prostate is composed of a higher amount of stromal tissue than epithelial tissue, as reflected by a stromal-to-epithelial tissue ratio of 2:1. This ratio is exaggerated to 5:1 for patients with BPH, which explains why α1-adrenergic antagonists are quickly effective in symptomatic management and why 5α-reductase inhibitors reduce an enlarged prostate gland by only 25%.2,3 The capsule, or outer shell of the prostate, is composed of fibrous connective tissue and smooth muscle, which also is embedded with α1-adrenergic receptors. When stimulated with norepinephrine, the capsule contracts around the urethra (Fig. 67-1).

FIGURE 67-1 Representation of the anatomy of and α-adrenergic receptor distribution in the prostate, urethra, and bladder. (Western J Med 1994;161:501. Reproduced with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group.)

Testosterone is the principal testicular androgen in males, whereas androstenedione is the principal adrenal androgen. These two hormones are responsible for penile and scrotal enlargement, increased muscle mass, and maintenance of the normal male libido. These androgens are converted by 5α-reductase in target cells to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), an active metabolite. Two types of 5α-reductase exist. Type I enzyme is localized to sebaceous glands in the frontal scalp, liver, and skin, although a small amount is in the prostate. DHT produced at these target tissues causes acne and increased body and facial hair. Type II enzyme is localized to the prostate, genital tissue, and hair follicles of the scalp. In the prostate, DHT induces growth and enlargement of the gland.3

In prostate cells, DHT has greater affinity for intraprostatic androgen receptors than testosterone, and DHT forms a more stable complex with the androgen receptor. Thus, DHT is considered a more potent androgen than testosterone in the prostate. Of note, despite the decrease in testicular androgen production in the aging male, intracellular DHT levels in the prostate remain normal, probably due to increased activity of intraprostatic 5α-reductase.3

Estrogen, a product of peripheral metabolism of androgens, is believed to stimulate the growth of the stromal portion of the prostate gland. Estrogens are produced when testosterone and androstenedione are converted by aromatase enzymes in peripheral adipose tissues. In addition, estrogens may induce the androgen receptor.2 As men age, the ratio of serum levels of testosterone to estrogen decreases as a result of a decline in testosterone production by the testes and increased adipose tissue conversion of androgen to estrogen.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although the precise pathophysiologic mechanisms causing BPH remain unclear, the role of intraprostatic DHT and type II 5α-reductase in the development of BPH is evidenced by several observations:

1. BPH does not develop in men who are castrated before puberty.

2. Patients with type II 5α-reductase enzyme deficiency do not develop BPH.

3. Castration causes an enlarged prostate to shrink.

4. Administration of testosterone to orchiectomized dogs of advanced age produces BPH.

The pathogenesis of BPH is often described as resulting from both static and dynamic factors. Static factors relate to anatomic enlargement of the prostate gland, which produces a physical block at the bladder neck and thereby obstructs urinary outflow. Enlargement of the gland depends on androgen stimulation of epithelial tissue and estrogen stimulation of stromal tissue in the prostate. Dynamic factors relate to excessive α-adrenergic tone of the stromal component of the prostate gland, bladder neck, and posterior urethra, which results in contraction of the prostate gland around the urethra and narrowing of the urethral lumen.

Symptoms of BPH disease may result from static and/or dynamic factors, and this must be recognized when drug therapy is considered. For instance, some patients may present with obstructive voiding symptoms but have prostates of normal size. In these patients, dynamic factors likely are responsible for the symptoms. However, for patients with enlarged prostate glands, static and dynamic factors likely are working in concert to produce the observed symptoms. Moreover, the likelihood of developing moderate to severe voiding symptoms is directly related to the increasing size of the prostate gland.4

Static factors may be accentuated if the patient becomes stressed or is in pain. In these situations, increased α-adrenergic tone may precipitate excessive contraction of prostatic stromal tissue. When the stressful event resolves, voiding symptoms often improve.2

MEDICATION-RELATED SYMPTOMS

![]() Medications in several pharmacologic categories should be avoided for patients with BPH because they may exacerbate symptoms.5 Testosterone replacement regimens, used to treat primary or secondary hypogonadism, deliver additional substrate that can be metabolized to DHT by the prostate. Although no cases of BPH have been reported because of exogenous testosterone administration, cautious use is advised for patients with prostatic enlargement. α-Adrenergic agonists, used as oral or intranasal decongestants (e.g., pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, or phenylephrine), can stimulate α-adrenergic receptors in the prostate, resulting in muscle contraction. By decreasing the caliber of the urethral lumen, bladder emptying may be compromised. β-Adrenergic agonists (e.g., terbutaline) may cause relaxation of the bladder detrusor muscle, which prevents bladder emptying.6 Drugs with significant anticholinergic adverse effects (e.g., antihistamines, phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, or anticholinergic drugs used as antispasmodics or to treat Parkinson’s disease) may decrease contractility of the urinary bladder detrusor muscle. For patients with BPH who have a narrowed urethral lumen, loss of effective detrusor contraction could result in acute urinary retention, particularly for patients with significantly enlarged prostate glands. Diuretics, particularly in large doses, can produce polyuria, which may present as urinary frequency, similar to that experienced by patients with BPH.

Medications in several pharmacologic categories should be avoided for patients with BPH because they may exacerbate symptoms.5 Testosterone replacement regimens, used to treat primary or secondary hypogonadism, deliver additional substrate that can be metabolized to DHT by the prostate. Although no cases of BPH have been reported because of exogenous testosterone administration, cautious use is advised for patients with prostatic enlargement. α-Adrenergic agonists, used as oral or intranasal decongestants (e.g., pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, or phenylephrine), can stimulate α-adrenergic receptors in the prostate, resulting in muscle contraction. By decreasing the caliber of the urethral lumen, bladder emptying may be compromised. β-Adrenergic agonists (e.g., terbutaline) may cause relaxation of the bladder detrusor muscle, which prevents bladder emptying.6 Drugs with significant anticholinergic adverse effects (e.g., antihistamines, phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, or anticholinergic drugs used as antispasmodics or to treat Parkinson’s disease) may decrease contractility of the urinary bladder detrusor muscle. For patients with BPH who have a narrowed urethral lumen, loss of effective detrusor contraction could result in acute urinary retention, particularly for patients with significantly enlarged prostate glands. Diuretics, particularly in large doses, can produce polyuria, which may present as urinary frequency, similar to that experienced by patients with BPH.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with BPH can present with a variety of symptoms and signs of disease. All symptoms of BPH can be divided into two categories: obstructive and irritative.

Obstructive symptoms, also known as prostatism or bladder outlet obstruction, result when dynamic and/or static factors reduce bladder emptying. The force of the urinary stream becomes diminished, urinary flow rate decreases, and bladder emptying is incomplete and slow. Patients report urinary hesitancy and straining and a weak urine stream. Urine dribbles out of the penis, and the urinary bladder always feels full, even after patients have voided. Some patients state that they need to press on their bladder to force out the urine. In severe cases, patients may go into urinary retention when bladder emptying is not possible. In these cases, suprapubic pain can result from bladder overdistension.

Approximately 50% to 80% of patients have irritative voiding symptoms, which typically occur late in the disease course. Irritative voiding symptoms result from long-standing obstruction at the bladder neck. To compensate, the bladder muscle undergoes hypertrophy so that it can generate a greater contractile force to empty urine past the anatomic obstruction at the bladder neck. Although initially helpful, decompensation eventually occurs, and the hypertrophied bladder muscle is no longer able to generate adequate contractile force as it becomes hypersensitive and ineffective in storing urine. As a result, small amounts of urine irritate the bladder and initiate a bladder emptying response. Patients complain of urinary frequency and urgency. Bedwetting or clothes wetting occurs. Patients report waking up every 1 to 2 hours at night to void (nocturia), which significantly reduces quality of life.

Symptoms of BPH vary over time. Symptoms may improve, remain stable, or worsen spontaneously. Thus, BPH is not necessarily a progressive disease; in fact, some patients experience symptom regression. Between one and two thirds of men with mild disease stabilize or improve without treatment over 2.5 to 5 years.2,4 However, other patients experience a slow progression of disease.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Collectively, obstructive and irritative voiding symptoms and their impact on a patient’s quality of life are referred to as lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). However, LUTS is not pathognomonic for BPH and may be caused by other diseases, such as neurogenic bladder and urinary tract infection.2

Another presentation of BPH is silent prostatism. Patients have obstructive or irritative voiding symptoms, but adapt to them and do not voluntarily complain about them. Such patients do not present for medical treatment until complications of BPH disease arise or a spouse brings in the symptomatic patient for medical care.

BPH can be a progressive disease, although the rate of progression is variable among patients.2,5 When BPH progresses, it can produce complications that include the following:

1. Acute, painful urinary retention, which can lead to acute renal failure

2. Persistent gross hematuria when tissue growth exceeds its blood supply

3. Overflow urinary incontinence or unstable bladder

4. Recurrent urinary tract infection that results from urinary stasis

5. Bladder diverticula

6. Bladder stones

7. Chronic renal failure from long-standing bladder outlet obstruction

Approximately 17% to 20% of patients with symptomatic BPH require treatment because of disease complications.7 Older men greater than 70 years of age with large prostates greater than 40 g and a postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume greater than 100 mL are three times more likely to have severe symptoms or suffer from acute urinary retention and to require prostatectomy than patients with smaller prostates.8–10 Thus, a serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 1.4 ng/mL (1.4 mcg/L) has been used as a surrogate marker for an enlarged prostate gland to identify patients at risk for developing complications of BPH disease6,10 and has been used to guide selection of the most appropriate treatment modality in some patients.11,12

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Because the obstructive and irritative voiding symptoms associated with BPH are not unique to the disease and can be presenting symptoms of other genitourinary tract disorders, including prostate or bladder cancer, neurogenic bladder, prostatic calculi, or urinary tract infection, the patient presenting with signs and symptoms of BPH must be thoroughly evaluated.

A careful medical history should be taken to ensure that a complete listing of symptoms is collected as well as to identify concomitant disorders that may be contributing to voiding symptoms. The medical history should be followed by a thorough medication history, including all prescription and nonprescription medications and dietary supplements that the patient is taking. Any drugs that could be causing or exacerbating the patient’s symptoms should be identified. If possible, the suspected drugs should be discontinued or the dosing regimen modified to ameliorate the voiding symptoms.

The patient should undergo a physical examination, including a digital rectal examination, although the size of the prostate gland may not correspond to symptoms. BPH usually presents as an enlarged, soft, smooth, symmetric gland, greater than 20 g in size. Some patients have only a slightly enlarged gland and yet have bothersome or even serious voiding difficulties. Other patients have intravesical enlargement of the prostate gland (i.e., the gland grows into the urinary bladder and produces a ball-valve blockage of the bladder neck). This type of prostate enlargement is not palpable on digital examination.

The patient’s perception of the severity of BPH symptoms guides selection of a particular treatment modality in a patient. To evaluate the patient’s perceptions objectively, validated instruments, such as the AUA Symptom Score (Table 67-1), are commonly used. Using the AUA Symptom Score, the patient rates the “bothersomeness” of seven obstructive and irritative voiding symptoms.2,13 Each item is rated for severity on a scale from 0 to 5, such that 35 is the maximum score and is consistent with the most severe symptoms. Patients usually are stratified into the three groups shown in the table based on disease severity for the purposes of deciding a treatment approach.

TABLE 67-1Categories of BPH Disease Severity Based on Symptoms and Signs

In addition, the patient can complete a voiding diary in which he records the number of voids, the volume of each void, and voiding symptoms for several days. This information is used to evaluate symptom severity and tailor recommendations for lifestyle modifications that may ameliorate symptoms.

The only clinical laboratory test that must be performed is a urinalysis. Because many of the voiding symptoms of BPH could be caused by other urologic disorders, a urinalysis can help screen for bladder cancer, stones, and infection. To screen for prostate cancer, another common cause of glandular enlargement, a PSA test should be performed for patients aged 40 years or more, with at least a 10-year life expectancy in whom the cost of the test will be outweighed by the potential benefit of diagnosing the disorder.13,14

Additional objective measures of bladder emptying should be performed if surgical treatment is being considered. Measures include peak and average urinary flow rate (normal is at least 10 mL/s). These measures are determined using an uroflowmeter, which checks the rate of urine flow out of the bladder. This is a quick noninvasive outpatient procedure in which the patient is instructed to drink water until his bladder feels full and then the patient’s urinary flow is clocked during voiding. A low urinary flow rate (<10 to 12 mL/s) implies failure of bladder emptying or a functional disorder of the detrusor muscle. Thus, the degree of bladder outlet obstruction may not correlate with peak urinary flow rate.13

Another objective measure is PVR urine volume (normal is 0 mL), which is assessed using a transabdominal ultrasound. A high PVR urine volume (<25 to 30 mL) implies failure of bladder emptying and a predisposition for urinary tract infections. Because of a weak correlation among voiding symptoms, prostate size, and urinary flow rate, most physicians use a combination of measures, including the patient’s assessment of symptoms along with objective evaluation of urinary outflow and presence of complications of BPH to determine the need for treatment.

Many other tests can be performed if additional information is needed to assess the severity of BPH disease and its complications, to assist in the preoperative assessment of the patient, or to distinguish prostate enlargement due to BPH from that caused by prostate cancer. Tests include a serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, voiding cystometrogram, transrectal ultrasound of the prostate, IV pyelogram, renal ultrasound, and prostate biopsy.

TREATMENT

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

The goals of treatment are to control symptoms, as evidenced by a minimum of a 3-point decrease in the AUA symptom index, prevent progression of complications of BPH disease, and delay the need for surgical intervention for BPH.

As a disease of symptoms, BPH is treated by relieving bothersome symptoms. However, selection of a single best treatment for a patient must consider the variable costs and adverse effects of treatment options, the inability to clearly distinguish patients who experience spontaneous regression or disease stabilization from those in whom symptoms progress, and the potential benefit that may occur in a comparatively small number of treated patients.

The AUA Guidelines on Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia is the principal tool used in the United States,13 and the AUA recommendations are similar to the European15 and Canadian Practice Guidelines (Fig. 67-2).16

FIGURE 67-2 Management algorithm for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

![]() All patients should be encouraged to initiate and maintain a heart healthy lifestyle, including a low-fat diet, high intake of plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, regular physical exercise, and no smoking.17 Specific treatment options include watchful waiting, pharmacologic therapy, and surgical intervention. Although phytotherapy is used by some patients alone or along with conventional medications for BPH, head-to-head comparisons with FDA-approved treatments are lacking; consequently, such herbals cannot be recommended at this time.

All patients should be encouraged to initiate and maintain a heart healthy lifestyle, including a low-fat diet, high intake of plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, regular physical exercise, and no smoking.17 Specific treatment options include watchful waiting, pharmacologic therapy, and surgical intervention. Although phytotherapy is used by some patients alone or along with conventional medications for BPH, head-to-head comparisons with FDA-approved treatments are lacking; consequently, such herbals cannot be recommended at this time.

![]() Patients with mild disease are asymptomatic or have mildly bothersome symptoms and have no complications of BPH disease. For these patients, no specific treatment is indicated. These patients can be managed with watchful waiting, which entails having the patient return for reassessment at intervals of 6 to 12 months. At each return visit, the patient should complete a standardized, validated survey tool to assess severity of symptoms. Watchful waiting should be accompanied by patient education about the disease and behavior modification to avoid practices that exacerbate voiding symptoms. Behavior modification includes restricting fluids close to bedtime, minimizing caffeine and alcohol intake, frequent emptying of the bladder during waking hours (to avoid overflow incontinence and urgency), and avoiding drugs that could exacerbate voiding symptoms.18 At each visit, physicians should assess the patient’s risk of developing acute urinary retention by evaluating the patient’s prostate size or using PSA as a surrogate marker of prostate enlargement.13

Patients with mild disease are asymptomatic or have mildly bothersome symptoms and have no complications of BPH disease. For these patients, no specific treatment is indicated. These patients can be managed with watchful waiting, which entails having the patient return for reassessment at intervals of 6 to 12 months. At each return visit, the patient should complete a standardized, validated survey tool to assess severity of symptoms. Watchful waiting should be accompanied by patient education about the disease and behavior modification to avoid practices that exacerbate voiding symptoms. Behavior modification includes restricting fluids close to bedtime, minimizing caffeine and alcohol intake, frequent emptying of the bladder during waking hours (to avoid overflow incontinence and urgency), and avoiding drugs that could exacerbate voiding symptoms.18 At each visit, physicians should assess the patient’s risk of developing acute urinary retention by evaluating the patient’s prostate size or using PSA as a surrogate marker of prostate enlargement.13

![]() If symptoms progress to the moderate or severe level, or the patient perceives his symptoms to be bothersome, the patient should be offered specific treatment. In these patients, watchful waiting delays—but does not decrease—the need for prostatectomy. In symptomatic patients, watchful waiting can lead to intractable urinary retention, increased PVR urine volumes, and significant voiding symptoms.18,19 Recommended treatment options include drug therapy with an α1-adrenergic antagonist or 5α-reductase inhibitor, a combination of an α1-adrenergic antagonist and a 5α-reductase inhibitor, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor or an anticholinergic agent; or surgery.

If symptoms progress to the moderate or severe level, or the patient perceives his symptoms to be bothersome, the patient should be offered specific treatment. In these patients, watchful waiting delays—but does not decrease—the need for prostatectomy. In symptomatic patients, watchful waiting can lead to intractable urinary retention, increased PVR urine volumes, and significant voiding symptoms.18,19 Recommended treatment options include drug therapy with an α1-adrenergic antagonist or 5α-reductase inhibitor, a combination of an α1-adrenergic antagonist and a 5α-reductase inhibitor, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor or an anticholinergic agent; or surgery.

Patients with serious complications of BPH should be offered surgical correction (transurethral or open prostatectomy, or a minimally invasive surgical procedure). Drug therapy is considered an interim measure for such patients because it only delays worsening of complications and the need for surgical intervention.13,18,19

Desired Outcomes

The desired outcomes of treatment include reducing LUTS as evidenced by an improvement of AUA Symptom Score by at least three points, an increase in the peak urinary flow rate, and a normalization of PVR to less than 50 mL. In addition, treatment should prevent the development of disease complications and reduce the need for surgical intervention. Treatment should be well tolerated and be cost-effective.

Personalized Pharmacotherapy

In selecting the most appropriate treatment for an individual patient, consideration should be given to the severity and quality of the patient’s LUTS, the likelihood of developing complications of BPH (based on size of the patient’s prostate gland), and the patient’s preference for medical versus surgical intervention.

Concurrent medical illnesses of the patient should also be considered. For example, if the patient has erectile dysfunction and moderate BPH, then a phosphodiesterase inhibitor might be preferred over a 5α-reductase inhibitor. If medical treatment is initiated, the patient’s level of renal function should be assessed, as the daily dose of some α-adrenergic antagonists and some anticholinergics require modification to avoid accumulation.

Pharmacologic Therapy

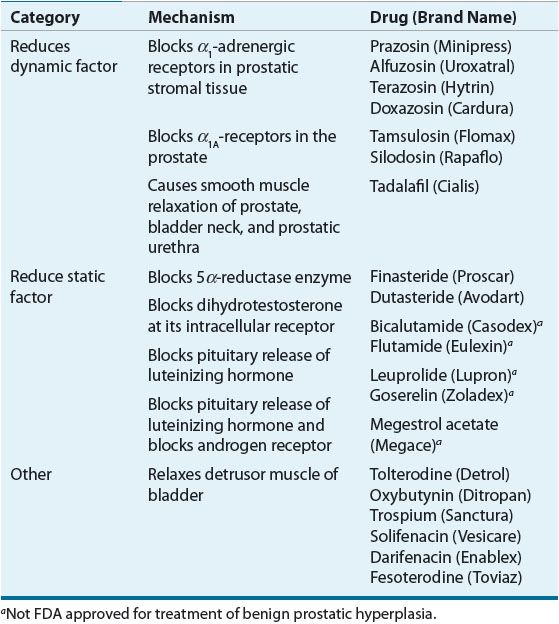

Drug therapy for BPH can be categorized into three types: agents that relax prostatic smooth muscle (reducing the dynamic factor), agents that interfere with testosterone’s stimulatory effect on prostate gland enlargement (reducing the static factor), and agents that relax bladder detrusor muscle (Tables 67-2 and 67-3). Of the agents that relax prostatic smooth muscle, second- and third-generation α1-adrenergic antagonists have been most widely used. These agents relax the intrinsic urethral sphincter and prostatic smooth muscle, thereby enhancing urinary outflow from the bladder. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors also relax bladder neck and prostatic smooth muscle. α1-Adrenergic antagonists and phosphodiesterase inhibitors do not reduce prostate size. Of the agents that interfere with testosterone’s stimulatory effect on prostate gland size, the only agents approved by the FDA are 5α-reductase inhibitors (e.g., finasteride, dutasteride). Other agents that interfere with androgen stimulation of the prostate have not been popular in the United States because of the many adverse effects associated with their use. The luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone superagonists leuprolide and goserelin decrease libido and can cause erectile dysfunction, gynecomastia, and hot flashes. Antiandrogens (e.g., bicalutamide, flutamide) produce nausea, diarrhea, and hepatotoxicity. Finally, antimuscarinic agents relax detrusor muscle contraction, which reduces irritable voiding symptoms in some patients with BPH.

TABLE 67-2 Medical Treatment Options for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia