(1)

Department of Pathology, Royal Victoria Hospital, Grosvenor Road, Belfast, UK

Abstract

This chapter covers the many benign endocervical glandular lesions, some of which may mimic premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions. Benign endocervical glandular lesions can be broadly divided into four groups, metaplasias and ectopias of endocervical glands, endocervical glandular “hyperplasias”, reactive and inflammatory lesions and benign glandular neoplasms. The differential diagnosis with premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions and the value of immunohistochemistry is discussed where appropriate.

Keywords

CervixBenign glandular lesionsImmunohistochemistryIntroduction

Within the cervix, there are many benign glandular lesions some of which are mimics of cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia (CGIN) or adenocarcinoma [1–3]. In general, these benign mimics are more common than premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions. Most pose no particular diagnostic problem and the majority, but not all, are typically incidental microscopic findings which rarely produce a mass lesion. In evaluating a possible problematic benign cervical glandular lesion, the pathologist should always look for more typical areas; for example, unusual forms of microglandular hyperplasia may pose a diagnostic problem but are often associated with areas of more typical microglandular hyperplasia. It should be remembered that rarely CGIN involves a pre-existing benign endocervical glandular lesion and this may result in obvious diagnostic problems. Ancillary immunohistochemical studies are of some value in the distinction of benign mimics from CGIN and adenocarcinoma [2, 3]. However, there are pitfalls and, as in all aspects of pathology, the results of immunohistochemistry should always be correlated with the morphology.

Benign endocervical glandular lesions can broadly be categorised into four groups:

1.

Metaplasias and ectopias of endocervical glands.

2.

Endocervical glandular “hyperplasias”.

3.

Reactive and inflammatory lesions.

4.

Benign glandular neoplasms.

Metaplasias and Ectopias of Endocervical Glands

Tubal Metaplasia, Tuboendometrial Metaplasia (TEM) and Superficial Endometriosis

These comprise a spectrum of glandular lesions which are common within the cervix. There are two distinct types of cervical endometriosis, each with a different underlying pathogenesis. Superficial (primary) endometriosis is usually unassociated with pelvic endometriosis whereas deep (secondary) endometriosis (endometriosis involving the external surface of the cervix) is associated with pelvic endometriosis [4]. Deep endometriosis is discussed in the next section. Superficial endometriosis is often part of a spectrum including tubal metaplasia and TEM. In this spectrum of metaplastic glandular lesions, the glands may exhibit tubal, endometrioid or intermediate features. With tubal metaplasia and TEM, there is often slight increased cellularity and condensation of the stroma around the glands and when definite endometrioid type stroma is present, this constitutes superficial endometriosis. The term tubal metaplasia is sometimes used when the glands exhibit overt tubal differentiation, although the term TEM is preferred since there is often an overlap of tubal and endometrioid differentiation. Often these glandular lesions occur in combination and, as stated, they are best regarded as being part of a spectrum. Glands exhibiting tubal features with ciliation are a normal occurrence at the junction of the cervix and endometrium in the lower uterine segment/isthmus [5]. However, tubal or endometrioid type glands are an abnormal, but common, finding close to the transformation zone of the cervix [6–8]. They represent a metaplastic, usually reparative, phenomenon, often secondary to previous cervical biopsy, resection or ablation. Occasionally they are seen in the absence of such a history. Uncommonly, superficial endometriosis may occur secondary to implantation, possibly as a result of menstruation or prior endometrial curettage.

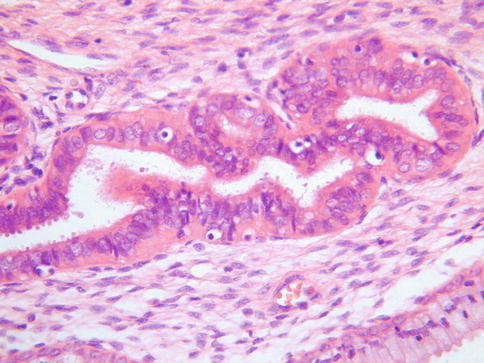

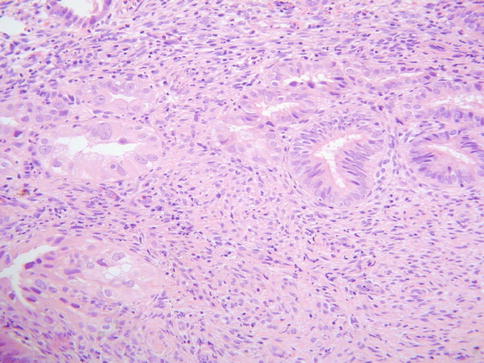

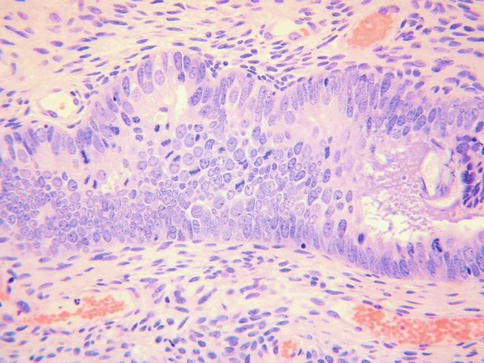

TEM may involve the surface glands or crypts and also sometimes dilated glands and Nabothian cysts. The morphology is usually, but not always, characterised by a heterogeneity of cell types. Ciliated and non-ciliated cells are present and there is often lymphocytic infiltration with intraepithelial lymphocytes, typically surrounded by a halo (Fig. 2.1). The non-ciliated cells may have apical snouts. There is nuclear stratification, mucin depletion, mild nuclear hyperchromasia and mild nuclear atypia; in occasional cases, some of the nuclei are quite atypical with an almost “symplastic-like” appearance but these are admixed with cells with bland nuclei (Fig. 2.2). Mitoses are sometimes present and occasionally are prominent, especially when the glands exhibit endometrioid differentiation (Fig. 2.3). Atypical mitoses are not seen. There may be a sharp demarcation between normal endocervical glands and glands involved by TEM or superficial endometriosis, both between adjacent glands and even within individual glands. The glands may be surrounded by true endometrioid stroma (superficial endometriosis), often with prominent engorgement of small vessels and extravasation of erythrocytes; these latter features are often a clue to the presence of endometrioid-type stroma which may otherwise be subtle (Fig. 2.4). There may be mild stromal condensation and hypercellularity surrounding the glands without overt endometrioid stromal differentiation (Fig. 2.5). CD10 immunohistochemical staining may be useful in helping to confirm the presence of endometrioid-type stroma, although normal cervical stroma immediately surrounding endocervical glands can be positive [9, 10]. Usually the glands conform to the normal endocervical glandular architecture but occasional cases of TEM with a pseudoinfiltrative appearance have been described, including rare cases associated with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol [11].

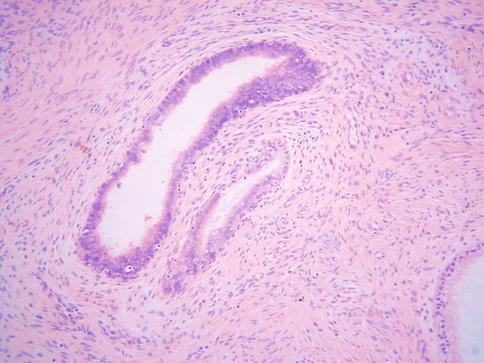

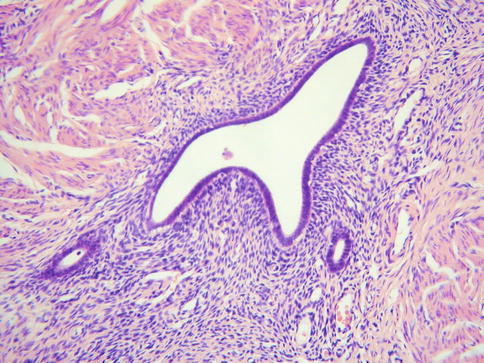

Fig. 2.1

Tuboendometrial metaplasia with ciliated and non-ciliated cells and lymphocytes surrounded by a halo

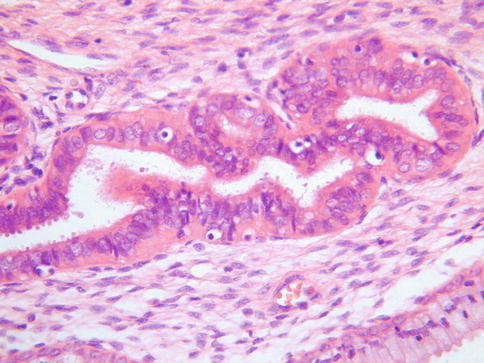

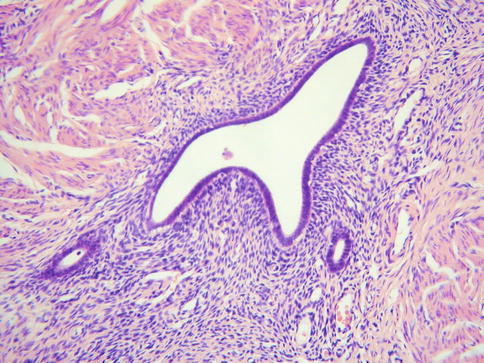

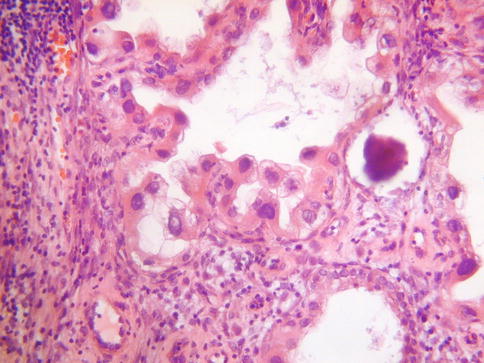

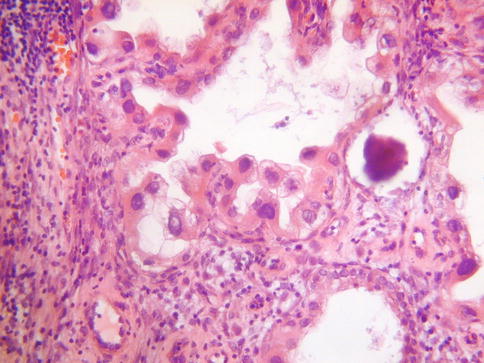

Fig. 2.2

In some cases of tuboendometrial metaplasia, there is quite marked nuclear atypia with an almost “symplastic-like” appearance

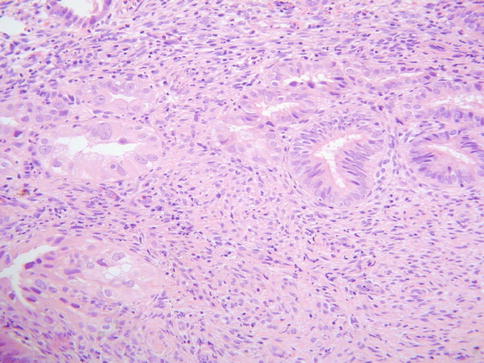

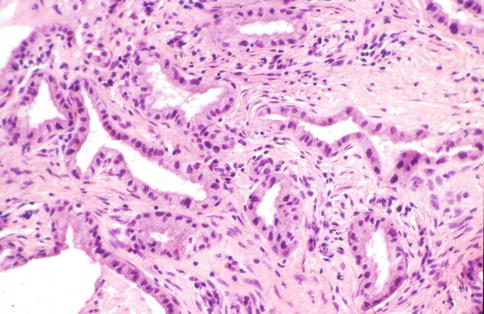

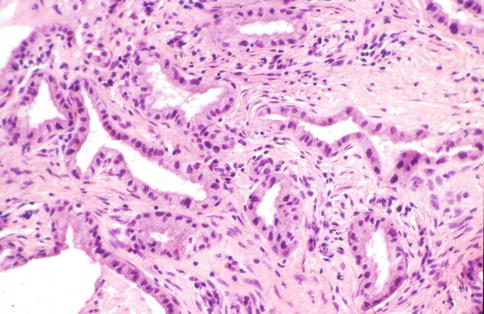

Fig. 2.3

In some cases of tuboendometrial metaplasia, mitoses are easily identified

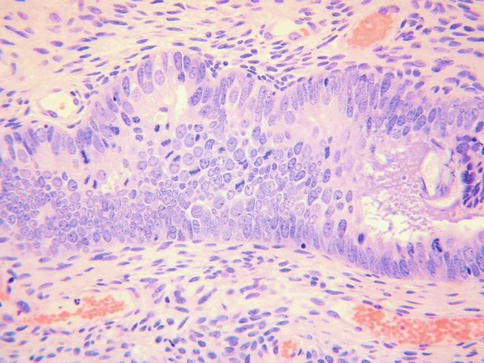

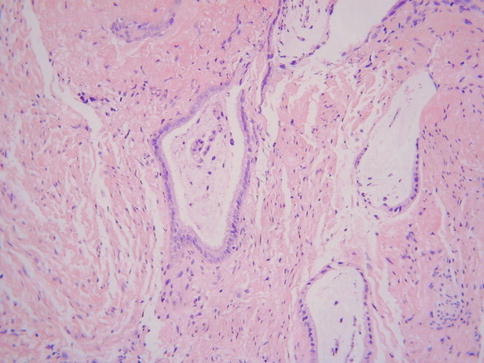

Fig. 2.4

Superficial endometriosis with endometrioid type glands and surrounding endometrioid type stroma

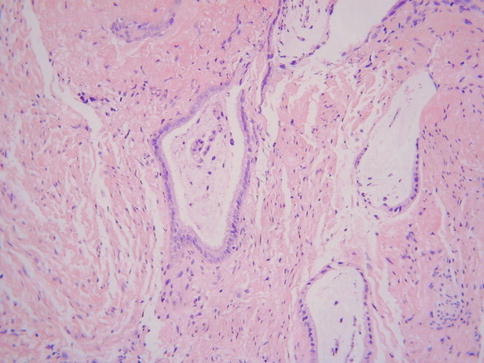

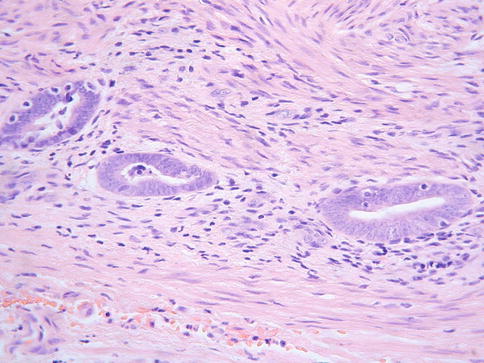

Fig. 2.5

In some cases of tuboendometrial metaplasia, there is stromal condensation and increased cellularity surrounding the glands

Stromal endometriosis characterised by the presence of endometrioid-type stroma without glands occasionally occurs within the cervix. This is characterised by the presence of small superficial nodules or plaques of endometrioid-type stroma, sometimes with prominent engorgement of small vessels and extravasation of erythrocytes (Fig. 2.6).

Fig. 2.6

Stromal endometriosis composed of aggregate of endometrial stromal cells without glands; there is engorgement of small vessels and extravasation of erythrocytes

In practice, this spectrum of lesions is the most likely within the cervix to be confused with CGIN. Features which may result in consideration of CGIN include the sometimes sharp demarcation from normal glands as well as nuclear stratification, nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia and mucin depletion. As discussed, mitoses are common, especially in cases exhibiting endometrioid differentiation, although abnormal mitotic figures are not a feature. Lymphocytes infiltrating the epithelium may mimic apoptotic bodies which are a feature of CGIN. Since TEM and superficial endometriosis are often a reparative phenomenon, there may be an associated stromal fibrotic or inflammatory reaction, rarely even mimicking an invasive adenocarcinoma.

Features useful in the distinction from CGIN include the presence of cilia in most examples of TEM and superficial endometriosis. However, cilia may not be prominent in those cases which exhibit overt endometrioid differentiation and a rare ciliated or tubal variant of CGIN exists [12]. Other points of distinction include the general absence of marked atypia in TEM and superficial endometriosis, except for occasional cases with “symplastic-type” nuclei (see above) and the fact that there are, in general, fewer mitotic figures with no abnormal mitoses. There are few or no apoptotic bodies and the nuclei are less hyperchromatic than is the case in CGIN. Endometrioid-type stroma may be present.

Immunohistochemistry may be of value in distinguishing TEM and superficial endometriosis from CGIN (see Table 3.2– Chap. on 3). A useful panel of markers is MIB1, bcl2 and p16 [13–15]. Other antibodies which may be of value are CEA, vimentin and oestrogen receptor (ER). In general, TEM and superficial endometriosis exhibit a low MIB1 proliferation index of less than 30 % (in most cases, less than 10 %) whereas CGIN usually exhibits a much greater MIB1 proliferation index, in excess of 30 %. However, there is some overlap at the lower end of the CGIN and the upper end of the TEM and superficial endometriosis spectrum, especially in cases of endometriosis or TEM with prominent endometrioid differentiation. TEM and superficial endometriosis usually exhibit diffuse cytoplasmic positivity with bcl2 (Fig. 2.7) whereas CGIN is negative. p16 may be of value in that CGIN almost always exhibits diffuse positivity (usually a combination of nuclear and cytoplasmic staining). TEM and superficial endometriosis may be negative but are often positive, although usually with focal immunoreactivity (Fig. 2.8). Cytoplasmic CEA immunoreactivity is characteristic of a premalignant or malignant endocervical glandular lesion and favours CGIN over TEM or superficial endometriosis. However, in practice this marker is of limited value since luminal positivity may be present in benign glandular lesions and normal endocervical glands while some premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions are negative; there is too much overlap in the CEA staining patterns between benign and premalignant or malignant endocervical glandular lesions for this marker to be of value in an individual case. Vimentin may be of value in that CGIN is usually negative whereas TEM and endometriosis exhibit cytoplasmic positivity [16, 17]. ER may similarly be of use since TEM and superficial endometriosis are usually diffusely positive while CGIN is negative or focally positive. These markers may also be useful in cauterised endocervical glandular epithelium, for example the distinction between cauterised TEM or superficial endometriosis and cauterised CGIN.

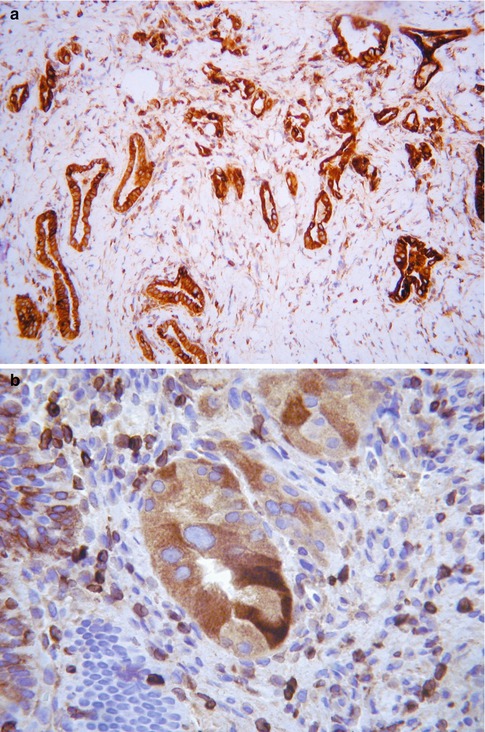

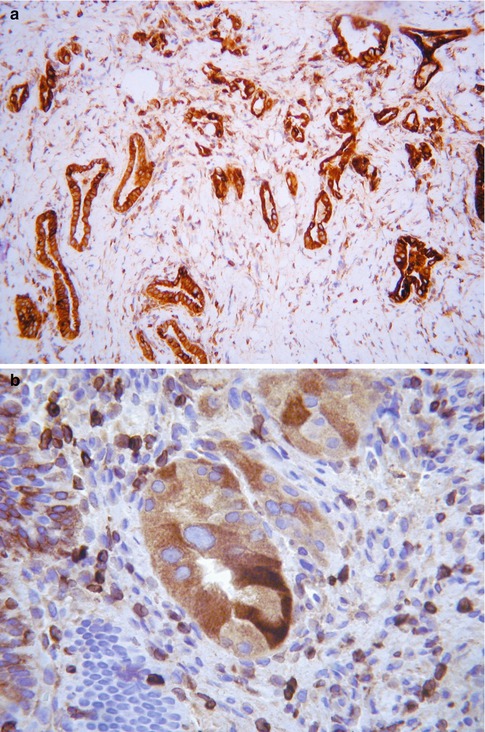

Fig. 2.7

Tuboendometrial metaplasia and tuboendometrial metaplasia with atypia exhibiting diffuse cytoplasmic staining with bcl2 (a, b)

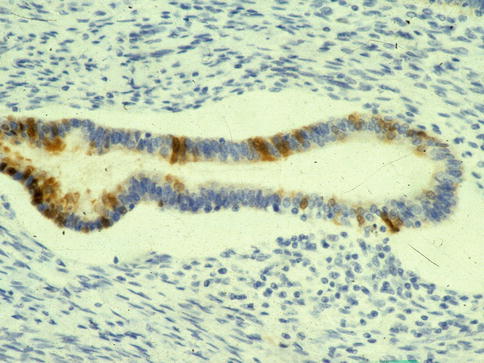

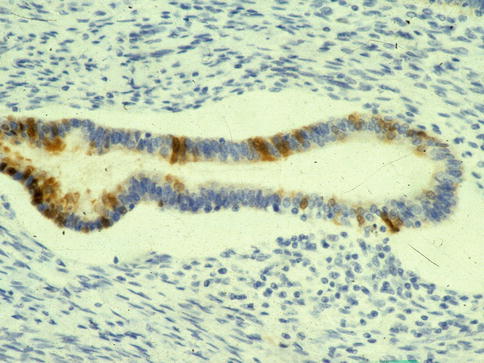

Fig. 2.8

Tuboendometrial metaplasia exhibiting focal staining with p16

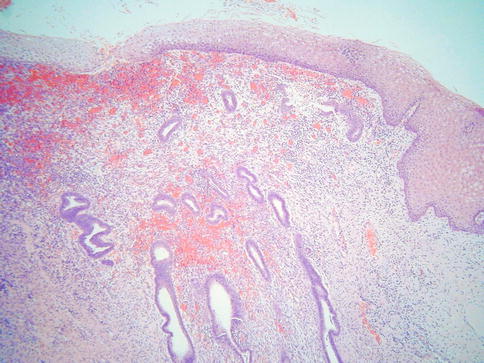

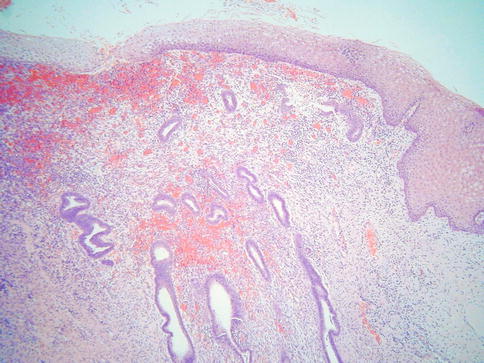

Deep Endometriosis

Although not a metaplasia of endocervical glands, deep endometriosis is discussed here. This is associated with pelvic endometriosis and, as such, is usually secondary to retrograde menstruation. It involves the outer aspects of the cervical stroma and paracervical connective tissues (Fig. 2.9). The morphological features are similar to endometriosis in other locations with endometrioid type glands and surrounding stroma.

Fig. 2.9

Deep cervical endometriosis with endometrioid type glands and surrounding endometrioid type stroma in outer aspects of cervix

Atypical Oxyphilic Metaplasia

This is a rare incidental microscopic finding characterised by the presence of endocervical glands lined by cuboidal or polygonal cells with somewhat atypical hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant dense eosinophilic cytoplasm, sometimes with apical snouts, the cytoplasmic appearances being the characteristic morphological feature of this lesion (Fig. 2.10) [18]. The nuclei may be multilobated and usually the changes are focal involving only a few glands or even a single gland. There is no mitotic activity. The features somewhat resemble apocrine metaplasia within the breast. Radiation atypia may have a very similar appearance and a history of prior pelvic irradiation should be excluded.

Fig. 2.10

Atypical oxyphilic metaplasia characterized by endocervical glands lined by cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and atypical hyperchromatic nuclei

Intestinal Metaplasia

Endocervical glands may exhibit intestinal differentiation which is characterised by the presence of goblet cells and rarely neuroendocrine or Paneth cells. Almost all examples of intestinal metaplasia involving non-invasive endocervical glands represent an intestinal variant of CGIN [19] (discussed in Chap. 3, Premalignant Glandular Lesions of the Cervix). While rare examples of “benign” intestinal metaplasia occur within the cervix, for example in association with lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia [20], this is extremely rare and true intestinal differentiation is almost always indicative of a premalignant or malignant lesion. In one reported case of “benign” cervical intestinal metaplasia, there was also gastric/pyloric metaplasia within the cervix and intestinal metaplasia within the endometrium [20], suggesting an occasional association between intestinal metaplasia at various sites within the female genital tract.

There have been occasional reported cases of intestinal-type epithelium lining the cervix secondary to spread from a primary appendiceal mucinous neoplasm [21]. In such cases, similar intestinal-type epithelium may line the endometrium and/or fallopian tube.

Simple Gastric (Pyloric) Metaplasia

Most examples of so-called gastric or pyloric metaplasia involving endocervical glands represent lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (LEGH) (See section on “Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia”). However, rarely endocervical glands without architectural features of LEGH exhibit immunoreactivity for HIK1083 [22, 23], a marker of pyloric gland mucins. In one study, Zhao et al. showed that the surface epithelium or crypt epithelium of non-neoplastic endocervical glands with a normal architecture were positive for pyloric gland mucin in 0.7 % of cases using this marker [23]. Such cases may be best designated as simple gastric (pyloric) metaplasia. Morphologically, this is extremely subtle and is characterized by pre-existing endocervical glands lined by columnar cells with abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, in contrast to the rather basophilic cytoplasm of normal endocervical glands. The significance of this is unknown but it may represent an early phase of LEGH. In the rare scenario of this being diagnosed in a biopsy specimen, the coexistence of prototypical LEGH is a concern and radiological examination is advised to look for the presence or absence of features suggestive of LEGH.

Arias-Stella Reaction

The Arias-Stella reaction (Arias-Stella effect) uncommonly involves endocervical glands, usually in association with pregnancy or, more rarely, hormonal preparations [24]. This is usually a focal finding involving the surface or crypt epithelium or sometimes the glands of an endocervical polyp. The histological features are well known and are similar to those seen within the endometrium, comprising cells with enlarged somewhat pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei with hobnail features, intraglandular papillary tufts and abundant clear vacuolated or eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2.11). Intranuclear pseudoinclusions, a cribriform architecture and occasional mitotic figures may be seen. Rarely, the Arias-Stella reaction may be mistaken for a premalignant or malignant lesion, most commonly a clear cell carcinoma. However, the history of pregnancy should result in a correct diagnosis. Useful in the distinction from clear cell carcinoma (this is only likely to be problematic on a small biopsy) is the absence of a mass lesion and of a desmoplastic response and infiltrative growth pattern and the fact that the Arias-Stella reaction is usually a focal finding involving a few glands. There is generally more atypia and mitotic activity in clear cell carcinoma, although some clear cell carcinomas may be cytologically bland with few mitotic figures. Stromal hyalinisation is characteristic of clear cell carcinomas.

Fig. 2.11

Arias-Stella reaction involving endocervical glands with atypical nuclei and hobnail cells

Endocervicosis

This rare condition may be viewed as the mucinous counterpart of endometriosis and can be associated with endometriosis and/or endosalpingiosis (collectively known as Mullerianosis). The most common sites of involvement are the outer aspects of the cervix (usually the anterior wall), the vagina, the bladder, the peritoneum and the pelvic lymph nodes [25, 26]. In the cervix, endocervicosis may be associated with a prior caesarean section and occasionally results in the formation of a mass lesion. The histological features are of glands lined by cytologically bland, or at the most mildly atypical, mucinous epithelium (Fig. 2.12). Mitotic figures are rare or absent. Some of the glands may be dilated and there can be minor foci of ciliated or endometrioid type glands. Helpful in the distinction from a mucinous variant of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum) is the fact that endocervicosis involves the outer aspects of the cervix and paracervical connective tissue with a zone of uninvolved tissue between the lesion and the native endocervical glands. There is minimal nuclear atypia and no desmoplastic stromal response, although there may be a focal stromal reaction to mucin extravasation. There is no vascular invasion, although perineural infiltration has been described [25]. Endocervicosis is a benign lesion but a single vaginal case with malignant transformation has been reported [27].

Fig. 2.12

Endocervicosis characterized by bland mucinous glands within outer cervical stroma

Endosalpingiosis/Florid Cystic Endosalpingiosis

Endosalpingiosis is usually an incidental microscopic finding and is characterised by the presence of benign glands lined by ciliated tubal type epithelium (Fig. 2.13). When occurring in the cervix, it involves the outer aspects of the stroma and the surrounding tissues. Rarely there is marked glandular dilatation resulting in the formation of multiple cysts, predominantly involving the serosa of the uterus, cervix, adnexae and intestine; this is referred to as florid cystic endosalpingiosis and in rare cases there is transmural involvement of the cervix [28]. While the bland cytological features usually result in a benign diagnosis, an adenocarcinoma, for example a minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of endometrioid type or an endocervical adenocarcinoma with cystic features, may be considered. Distinction from TEM is based on the location of the tubal type glands, TEM being situated superficially within the cervix while endosalpingiosis predominantly involves the outer aspect and surrounding tissues.

Fig. 2.13

Endosalpingiosis characterized by ciliated tubal type glands in outer aspects of cervical stroma

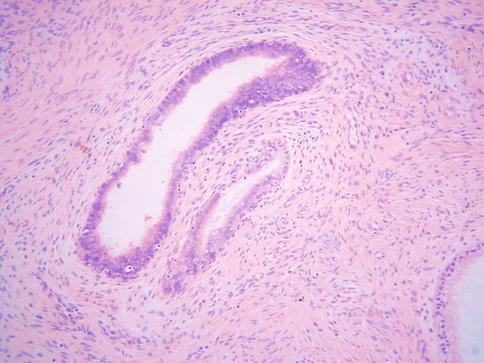

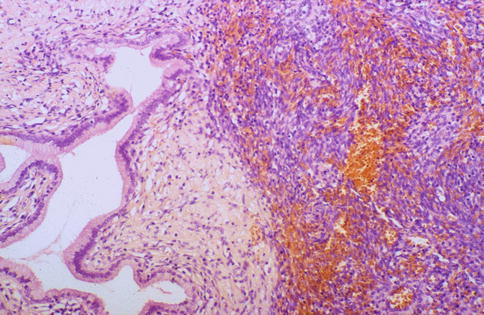

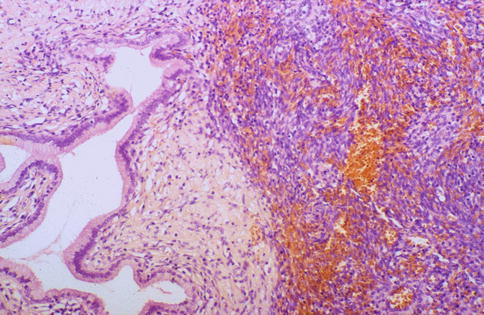

Ectopic Prostatic Tissue

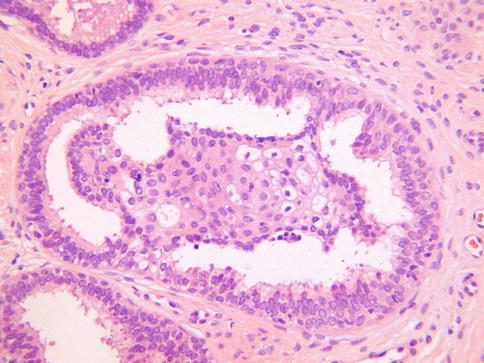

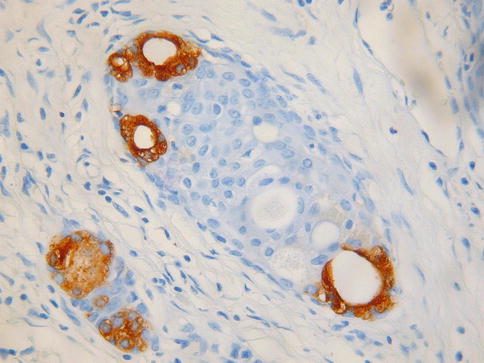

So-called ectopic prostatic tissue is uncommon within the cervix and is usually an incidental microscopic finding, although in very rare cases a mass lesion is formed [29–31]. There is debate whether this represents a developmental anomaly or a metaplasia of endocervical glands. The “prostatic” tissue may be present superficially or deep within the cervical stroma and is usually located predominantly in the ectocervix rather than at the transformation zone, although sometimes the transformation zone is involved; the typical ectocervical location is evidence that this represents a developmental anomaly rather than a metaplasia of endocervical glands.

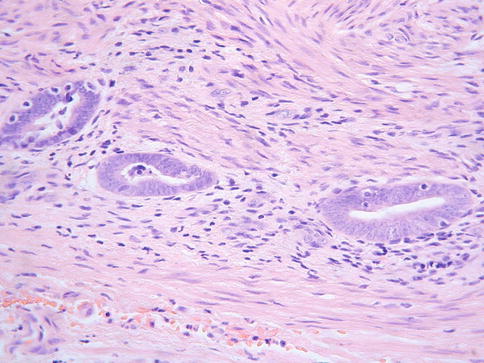

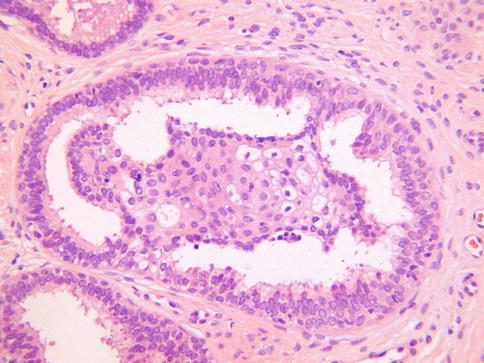

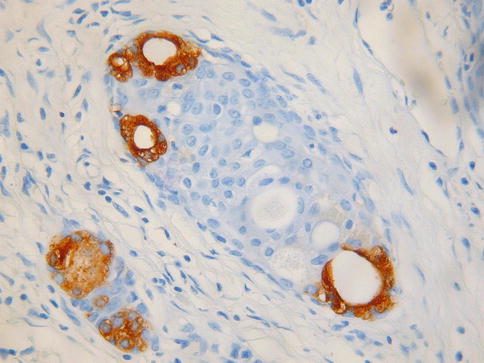

The basic morphological appearance is of rounded epithelial elements of both glandular and squamous type; tubules lined by bland epithelium are typically present around the periphery of the squamous elements and, in some cases, the glandular elements, at least focally, form a double cell layer (Fig. 2.14). Cribriform and papillary patterns are common. Although the glandular element of ectopic prostatic tissue is typically positive with prostate specific antigen and prostatic acid phosphatase (Fig. 2.15), this is not always the case. Occasional examples are negative with one or both markers and often positive staining is focal rather than diffuse. Prostatic acid phosphatase is more likely to be positive than prostate specific antigen [31]. p63 and other basal markers highlight the presence of a basal cell layer within the glandular or tubular elements.

Fig. 2.14

Ectopic prostatic tissue in cervix characterized by squamous and glandular elements, the latter lined by a double cell layer

Fig. 2.15

Ectopic prostatic tissue in cervix is focally positive with prostatic acid phosphatase

An uncommon vaginal polyp, referred to as vaginal tubulosquamous polyp, is morphologically similar to cervical ectopic prostatic tissue and may exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining with prostatic markers [31, 32]. It is thought that cervical ectopic prostatic tissue and vaginal tubulosquamous polyp are derived from paraurethral Skene’s glands which are the female equivalent of prostatic glands in the male [31, 32]. Uncommon findings in these lesions include the presence of sebaceous glands, basaloid formations resembling hair follicle structures and a microglandular proliferation resembling nephrogenic adenoma [31]. Occasionally, similar microscopic lesions are seen in the vulva [31, 33]. It has been proposed that these benign lesions in the cervix, vagina and vulva, which may exhibit immunoreactivity with prostatic markers, are derived from eutopic or misplaced Skene’s glands [31].

Sebaceous Glands and Hair Follicle Structures

So-called ectopic sebaceous glands are a rare incidental microscopic finding within the cervix (Fig. 2.16); they may also be found in the vagina [34–38]. They are usually attached to or situated just beneath the ectocervical squamous epithelium and are possibly more common in association with uterine prolapse. The overlying squamous epithelium may be keratinised and occasionally hair follicle structures are also present, sometimes forming pilosebaceous units in association with sebaceous glands; rarely sweat gland-like structures are present [38]. It has been debated whether ectopic ectodermal structures (sebaceous glands, hair follicles and sweat glands) in the cervix and vagina are a result of congenital misplacement or an acquired metaplastic change [34–38]; the latter theory is preferred whereby the ectodermal structures are a response to prolonged irritation or chronic injury [38].

Fig. 2.16

Ectopic sebaceous glands within superficial cervical stroma

Endocervical Glandular Hyperplasias

It is arbitrary as to what constitutes an endocervical glandular hyperplasia, since normal endocervical glands may vary considerably in prominence, depending amongst other things on the menopausal status and parity of the patient and whether exogenous hormones are being taken. There is little point in rendering a diagnosis of non-specific endocervical glandular hyperplasia and this terminology is not recommended. However, there are several lesions, including some where the term hyperplasia is used, which should be recognised by the pathologist.

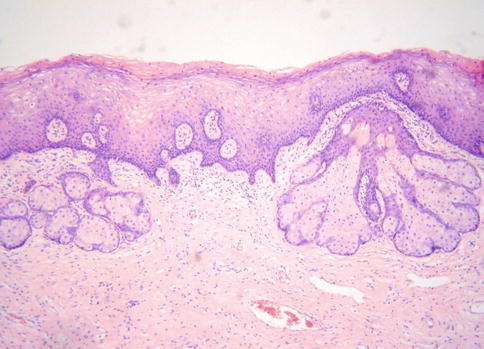

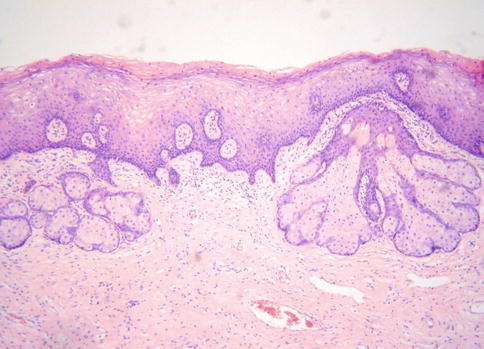

Tunnel Clusters

Tunnel clusters are a relatively common, usually incidental, microscopic finding within the cervix, although uncommonly they are visible grossly. Rarely, they are associated with a mucoid vaginal discharge. They were first described by Fluhmann in 1961 [39] and are divided into type A (non-cystic) and type B (cystic) variants; type B is much more common [40, 41]. Tunnel clusters are usually superficially located within the cervix but occasionally extend quite deeply. There is some degree of overlap between type A and B with occasional cases exhibiting an admixture of patterns. There is an association with parity and it has been suggested that tunnel clusters represent involution of pregnancy associated “hyperplastic” endocervical glands [40, 41].

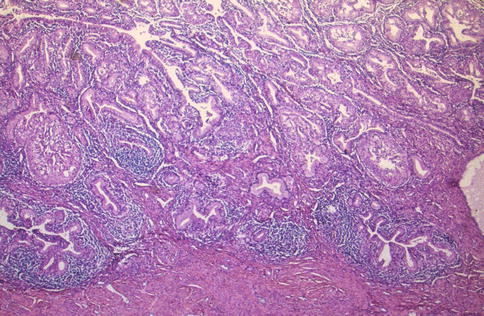

The more common type B tunnel clusters have a characteristic low power appearance with well demarcated clusters of closely packed, dilated endocervical glands with a lobular architecture (Fig. 2.17). The clusters may be multifocal. On high power, the glands are lined by flattened epithelium with minimal intracytoplasmic mucin. There is little or no nuclear atypia or mitotic activity. Sometimes, there is mucin extravasation with an associated stromal reaction in the form of histiocytes and other inflammatory cells. Although the histological features of type B tunnel clusters are characteristic they may rarely be mistaken for adenoma malignum or an adenocarcinoma with cystic features, either a microcystic variant of usual endocervical type adenocarcinoma [42] or a cystic variant of clear cell carcinoma. However, the absence of a mass lesion and of nuclear atypia and stromal desmoplasia are in favour of a benign lesion; in fact, it is more likely to misdiagnose a cystic variant of adenocarcinoma as tunnel clusters.

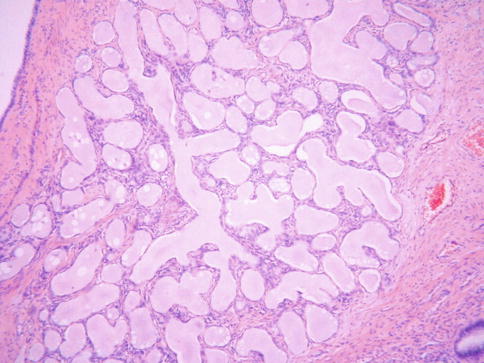

Fig. 2.17

Type B tunnel clusters characterized by lobular arrangement of glands with cystic dilatation

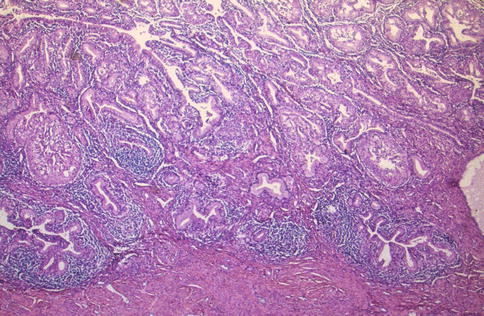

Type A tunnel clusters are characterized by a lobular proliferation of predominantly small-calibre, nondilated, closely packed glands which may be arranged around a central endocervical cleft (Fig. 2.18). Most are well circumscribed but occasionally there is a slightly irregular border with a pseudoinfiltrative appearance which can result in consideration of an adenocarcinoma. The glands are lined by columnar or low cuboidal cells containing intracytoplasmic mucin. Occasional cases exhibit mild cytologic atypia and there can be a degree of hypercellularity of the stroma surrounding the glands but there is no desmoplasia [40]. These features, together with the pseudoinfiltrative appearance, may result in consideration of adenocarcinoma.

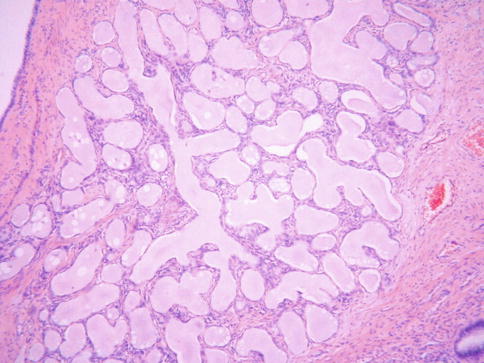

Fig. 2.18

Type A tunnel clusters consisting of non-dilated glands

It has been shown that some type A tunnel clusters, in contrast to normal endocervical glands and type B tunnel clusters, contain neutral mucins and exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining with antibodies against gastric/pyloric mucins, such as HIK1083 and MUC6. Along with lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia, type A tunnel clusters may be part of a spectrum of benign endocervical glandular lesions exhibiting gastric differentiation; in fact, some type A tunnel clusters may represent an early or incipient form of lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (see section on “Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia”) [22, 43, 44].

Lobular Endocervical Glandular Hyperplasia (LEGH)

LEGH is an uncommon cervical lesion [45, 46]. While this is most commonly an incidental microscopic finding, sometimes there is a mass lesion which may be “picked up” on radiological examination. Some patients present with watery vaginal discharge and occasional patients have Peutz Jeghers syndrome. LEGH is usually situated in the upper part of the endocervical canal close to the internal os rather than at the transformation zone. Morphologically, this constitutes a well demarcated lesion which is usually confined to the inner half of the cervix. It is characterised by the presence of small glands arranged in a lobular fashion surrounding larger glands or duct-like structures; the ducts and lobular elements are lined by low columnar cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and basally located small bland nuclei (Fig. 2.19a). Sometimes there is mild nuclear atypia and/or occasional mitotic activity. Intraglandular bridging or a cribriform architecture may be seen focally. Occasionally, there is a focal diffuse architecture rather than the normal lobular pattern. Rarely, there is focal intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells, especially within the centrally located glands (Fig. 2.19b). Hormone receptors (ER and PR) are negative (Fig. 2.19c), in contrast to normal endocervical glands and most other benign cervical glandular lesions [22, 45–47]. Cytokeratin (CK) 7 and 20 are positive and negative respectively and CEA is positive only in the apical aspect of the columnar cells, in contrast with the cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in most adenocarcinomas. There may be scattered chromogranin A and/or synaptophysin-positive neuroendocrine cells

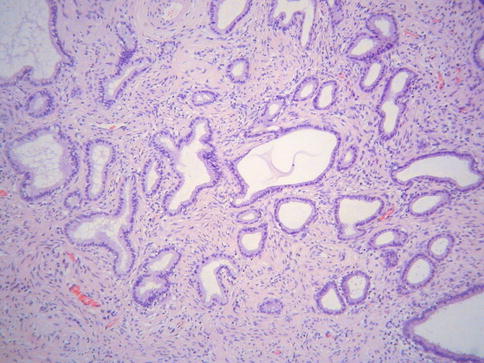

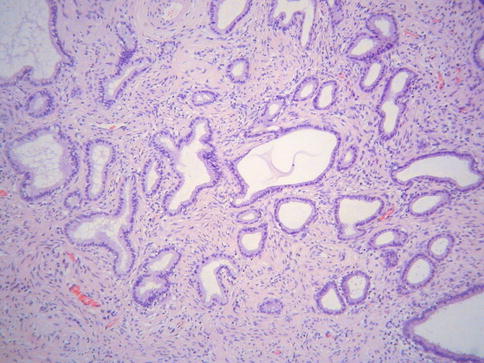

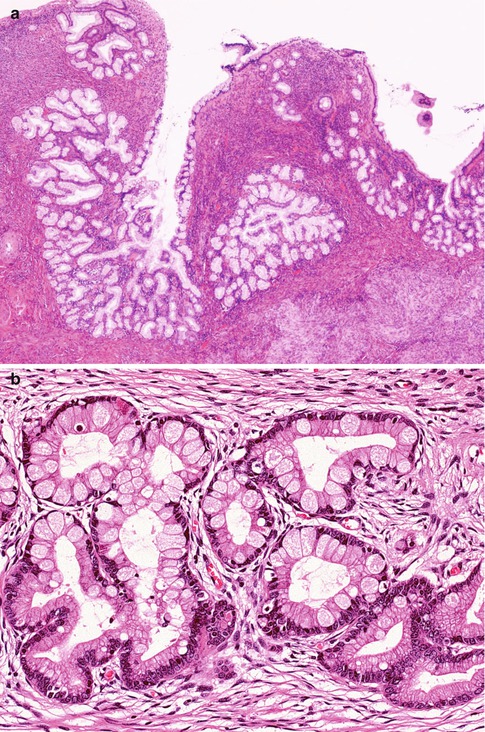

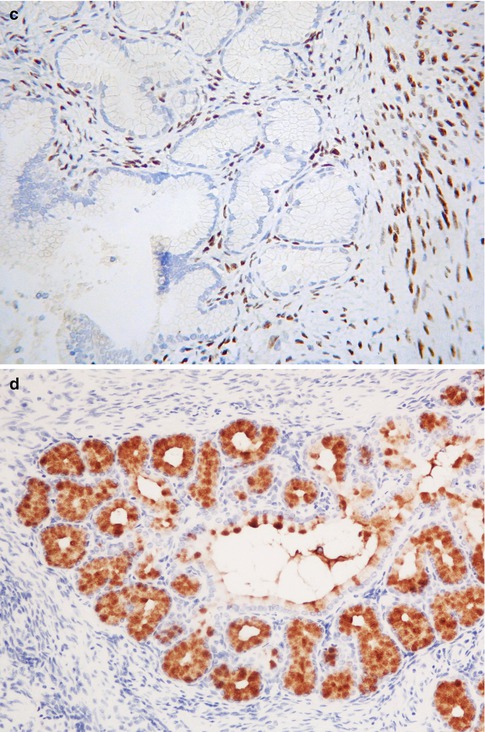

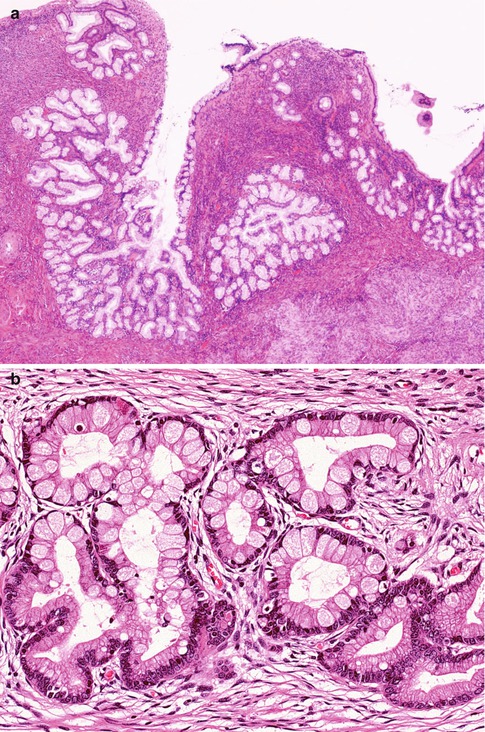

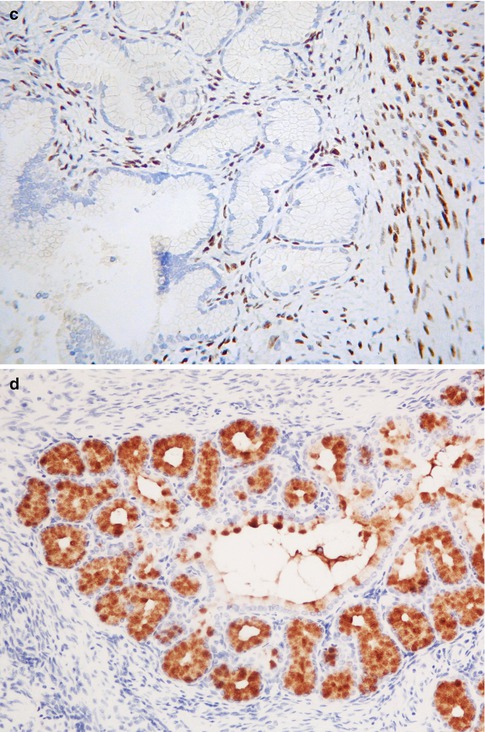

Fig. 2.19

Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia characterized by central duct-like structure and surrounding lobules (a). Rarely there is focal intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells (b). ER is negative but positive in the surrounding stromal cells (c). There is positive staining with HIK1083 (d)

LEGH, along with type A tunnel clusters, has been proposed to be part of a spectrum of benign cervical glandular lesions exhibiting gastric/pyloric differentiation [22]. These various glandular lesions contain neutral mucins and stain red with combined Alcian-blue/PAS while normal endocervical glands stain a purple-violet colour due to their admixture of acid and neutral mucins [48]. These gastric lesions are also positive with HIK1083 (Fig. 2.19d) and MUC6, markers of pyloric gland mucins [49–51]. Comparing these two markers, HIK1083 is more specific but less sensitive while MUC6 is more sensitive but less specific; staining with both markers, especially HIK1083, is often focal. There are also a variety of premalignant and malignant cervical glandular lesions exhibiting gastric differentiation (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1

Endocervical glandular lesions exhibiting gastric differentiation

Benign | Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (complex pyloric/gastric metaplasia) |

Simple gastric/pyloric metaplasia | |

Tunnel cluster (type A) | |

Possible in situ/premalignant | Atypical lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia |

Adenocarcinoma in situ of gastric type | |

Malignant | Gastric type adenocarcinomaa |

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum)a | |

Specific clinical or clinicopathologic conditions | Synchronous mucinous metaplasia and neoplasia of the female genital tract (SMMN-FGT) |

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome |

Although extremely uncommon, atypical variants of LEGH have been described which are characterised by cytological abnormalities (mild nuclear atypia and mitotic activity) and/or architectural abnormalities, mainly in the form of short papillary projections, and it has been proposed that these represent a precursor of cervical adenocarcinomas exhibiting gastric differentiation [52–54]. In one study, comparative genomic hybridization revealed recurrent chromosomal imbalances, in the form of gains of chromosome 3q and a loss of 1p (aberrations which are common in minimal deviation adenocarcinoma and other cervical mucinous adenocarcinomas), in 3 of 14 LEGHs analyzed (21 %) [54]. LEGHs with chromosomal imbalances exhibited a degree of cellular atypia in the hyperplastic glandular epithelium. Dual-colour fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed a gain of chromosome 3 fragment in these cervical glandular lesions. This study demonstrated a molecular-genetic link between LEGH and cervical mucinous adenocarcinomas, including adenoma malignum, supporting the hypothesis that a proportion of LEGHs (atypical LEGH) are precancerous precursors of gastric type adenocarcinomas. Gastric type mucinous glandular lesions in the cervix may be associated with synchronous mucinous lesions, including metaplasias and neoplasms, elsewhere within the female genital tract, for example the endometrium, fallopian tube and ovary; in some cases, it may be problematic to ascertain whether these represent synchronous independent mucinous lesions or metastatic disease from one site to another [55–57].

The morphological features of LEGH may result in consideration of an adenocarcinoma, especially adenoma malignum (mucinous variant of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) and in occasional examples of the latter neoplasm there are areas resembling LEGH, providing evidence that LEGH may, in some cases, represent a precursor lesion of adenoma malignum. The distinction from adenoma malignum is facilitated by the usual absence of an obvious tumour mass in LEGH, its location high in the endocervical canal, its more superficial location, lobular architecture, absence of irregular stromal infiltration and a desmoplastic stromal reaction, no evidence of focal nuclear atypia and no evidence of vascular or perineural infiltration. It has been suggested that a combination of ER and smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining may assist in the distinction [47]. In LEGH and other benign glandular lesions, the stroma surrounding the glands is ER positive and largely SMA negative while in adenoma malignum and other adenocarcinomas, the stroma is SMA positive and there is a decrease in staining with ER as a result of the desmoplasia [47].

While LEGH per se is a benign condition, occasionally an adenocarcinoma can be associated with this (see Chap. 4, section on “Mucinous variant of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma”). Those adenocarcinomas which are associated with LEGH are of gastric type, including adenoma malignum. Therefore, some gynaecologists or patients may prefer hysterectomy in cases of LEGH diagnosed on loop excision to confirm that there is no co-existing adenocarcinoma. Loop excision with close surveillance, especially where fertility preservation is an issue, is also an option. Currently, the exact risk of coexistence or future development of adenocarcinoma is unknown, although this is likely to be low. However, in the presence of a clinically significant mass and/or massive watery vaginal discharge, the patient should be managed with caution.

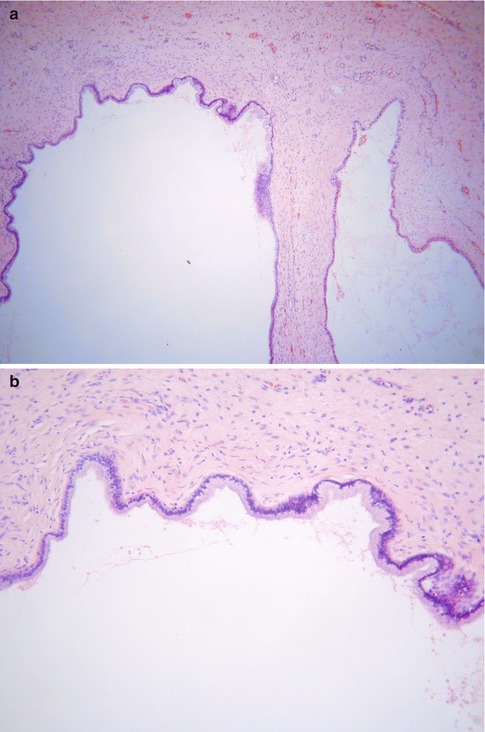

Diffuse Laminar Endocervical Glandular Hyperplasia (DLEGH)

This rare lesion is an incidental microscopic finding within the cervix and usually occurs within the reproductive years [58]. It is characterised by a band-like proliferation of endocervical glands which is sharply demarcated from the underlying stroma such that a straight line can almost be drawn under the proliferation (Fig. 2.20). DLEGH is usually confined to the inner third of the cervix and is characterised by the presence of moderately sized, evenly spaced, closely packed glands. There may be mild nuclear atypia and an inflammatory or oedematous stromal reaction. Adenoma malignum (mucinous variant of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) may be considered in the differential. Features that assist in this distinction are that in DLEGH, there is no mass lesion, irregular stromal infiltration, desmoplastic stromal response or focal malignant cytological features.

Fig. 2.20

Diffuse laminar endocervical glandular hyperplasia consisting of proliferation of endocervical glands with an associated inflammatory infiltrate; a straight line can be drawn under the proliferation

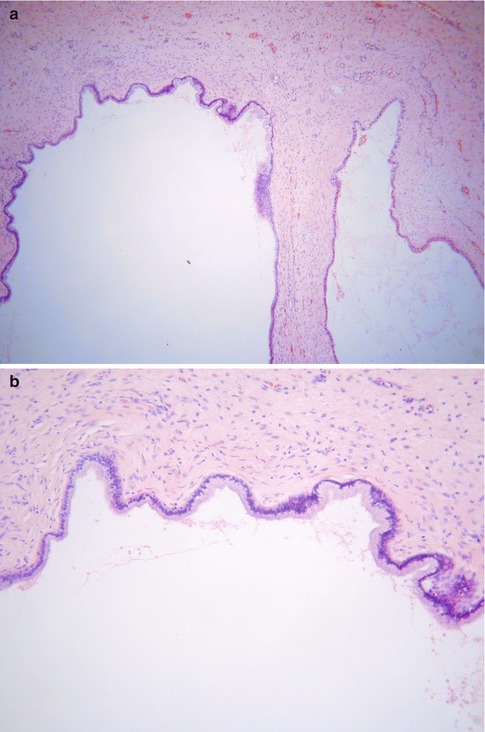

Deep Glands and Nabothian Cysts

Occasionally normal endocervical glands and dilated glands (Nabothian cysts) are located deep within the cervical stroma, sometimes extending close to the paracervical connective tissues (Fig. 2.21) [59, 60]. The Nabothian cysts may be visible macroscopically. The glands and cysts are lined by bland mucinous epithelium which may be focally or extensively attenuated. Sometimes there is focal tubal differentiation with cilia. When the features are florid, deep glands and cysts may be confused with adenoma malignum but the overall appearances differ from the latter and misdiagnosis is unlikely. There is no evidence of focal cytologic atypia and there is an absence of a desmoplastic stromal reaction, vascular and perineural invasion.

Fig. 2.21

Deep Nabothian cysts within cervical stroma (a). On high power, the deep Nabothian cysts are lined by bland mucinous epithelium (b)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree