OVERVIEW

- CBT works by helping patients find ways to change their behaviour and put those changes into practice

- Behaviour change involves setting SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time orientated) targets and managing activity

- Activity management includes monitoring, activity scheduling, graded changes in activity and sleep management.

Introduction

The behavioural component of a CBT approach to medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) aims to help the patient move from having their activities dictated by symptoms towards regaining some control over their life. However, the symptom-led pattern of activity is there for a reason: people avoid symptoms because symptoms are terrible. Avoiding them makes sense.

CBT, it is NOT just ‘do more exercise’

As clinicians, we may know that increasing activity should help a patient’s mood, pain and fatigue, but that knowledge can make us prescriptive. For the patient to gradually wrest control of their life away from their symptoms, they also need to be in control of their treatment. They need to come to a realisation that changing their behaviour makes a difference; that realisation may be hard won. The job of the clinician or therapist is to provide the patient with a plausible rationale to try doing things differently, and to offer support as the patient makes these attempts for themselves. As such, the formulation skills discussed in the previous chapter are an important preliminary to behavior change.

Know where you are going

To get better means to do better. Before beginning treatment, cognitive or behavioural, it is a good idea to get an idea of what the patient would be doing differently if they were feeling better. This gives targets to work towards and also a clue of how to get there, step by step. Box 16.1 is an example of getting from the general aim to a particular target.

Therapist: Ok, so if your pain was better, and you were generally feeling better, what would you be doing that you can’t do now?

Patient: Well, I’d probably be socialising a lot more.

Therapist: What would you be doing socially?

Patient: I’d see my sister a lot more for a start.

Therapist: How often would you see her if you were feeling better?

Patient: Oh, probably twice a week like we used to. We used to go for coffee in our local café twice a week. I can’t now, its too noisy, and I’m too worn out.

Therapist: Ok, so if you were feeling better, you would see you sister in your local café, twice a week. How long would you see her for?

Patient: Oh, we used to sit for at least an hour.

Therapist: And that’s what you would like to do again?

Patient: Yes.

Therapist: Ok, so one of your treatment targets could be to go to the local café with your sister twice a week for an hour each time?

This target has now moved from the general to the specific; it is now SMART : Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time orientated. Having established this target, the next step is to start finding steps to take towards it. For instance an intermediate goal for the patient in Box 16.1 might be seeing her sister in her own home for half an hour. The SMART goal is also a motivator. Activity towards a valued goal is more likely to be continued when things are difficult than an arbitrary goal set by the physician.

Activity management(s)

There are three types of activity management. Activity scheduling is useful where low mood is associated with loss of pleasure and general withdrawal or conversely where fear of failing leads to overactivity. Graded activity is useful in pain and fatigue. Sleep management is used wherever there is sleep disturbance, which is a common feature of all MUS. Often, different types of activity management are used in conjunction.

Monitoring activity

The first step in all activity management is self-monitoring. When clinician and patient have identified a specific area, for instance sleep or activity, then the monitoring begins with a diary. Combined with some sleep or activity advice, this becomes the homework between sessions. In CBT it is important to emphasise that it is what people change between sessions, not what is said in sessions, that helps them get better.

Below are some of the common activity patterns in MUS that will emerge from a diary. Changing these patterns will make a difference.

Overactivity

You can spot this one because, when you go through it with the patient: you feel exhausted yourself! Overactive people sometimes devote all their energy to work. Introducing rest will be important, but equally important is variety of activity. Having fun can be as restorative as rest.

Underactivity

What is too little? When it is substantially less than they did before. If people are at home a lot, not going out much, walking little and socially withdrawn, all of these will contribute to both low mood and fatigue and experience of physical symptoms. Excessive daytime rest and/or sleep will also disturb night-time sleep.

Inconsistent or ‘boom and bust’ activity

This is a common pattern in MUS. It tends to follow the pattern of long stretches of activity, with little rest, followed by ‘crashing out’. This may happen within a day (work all day, crash in the evening) or over several days (work all week crash at weekend). Although patients may not recognise it, this usually indicates that patients are using symptoms to dictate activity.

Loss of pleasurable activity

This can fit into any of the patterns described above, but is worth highlighting on its own. It is particularly marked in low mood where people often stop doing the things they enjoy.

Once the activity patterns become apparent, there are ways to change them. As with other things the CBT model involves presenting the client with a hypothesis—that their activity may be involved in how they feel, and that by changing their activity pattern they can change how they feel. This is a process of negotiation, and collaboration is essential.

Activity scheduling

This is useful for low mood, loss of pleasure or pleasurable activities, overworking, lack of motivation.

The rationale is that low mood or lack of motivation lead to stopping pleasurable activities and loss of sense of achievement. In turn this leads to low mood and lack of motivation. By deliberately ‘push starting’ activity again, pleasure and/or motivation will return.

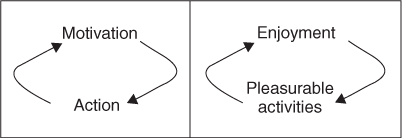

Often people will say—‘I just don’t have the motivation anymore, if I could only get that back, I’ll start doing things again’. But the link between action and motivation is reciprocal, not one-way, as shown in Figure 16.1. When asked, most patients can think of instances where motivation has followed action rather than the other way round, or when they have enjoyed something they nearly did not do. Sometimes it helps to use analogy. A common one is starting an engine on a cold morning: you need to give it a push to start it off. Waiting for motivation to return in someone with low mood is rather like waiting for the engine to start itself.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree