Erika Litvin Bloom, PhD, Christopher W. Kahler, PhD, Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, and Richard A. Brown, PhD

59

RELEVANCE FOR ADDICTIONS TREATMENT

About 50% to 80% of all patients involved in substance abuse treatment indicate an interest or desire to quit smoking. Studies have found that inclusion of smoking cessation treatment in the context of other addiction programming does not reduce long-term treatment completion. Furthermore, most studies have found that smoking cessation interventions initiated during treatment do not harm treatment outcome and may even be associated with better drinking outcomes. Recent studies have concluded that nicotine replacement therapy results in improved smoking abstinence rates. The use of pharmacotherapy may be especially important given that patients with alcohol and drug use disorders tend to smoke more per day than do those without alcohol and drug use disorders.

Whether to initiate smoking cessation treatment early in the course of substance abuse treatment or to wait until sobriety has been attained for a few months remains a question. Greater lengths of sobriety from alcohol are positively associated with improved smoking cessation outcomes, suggesting that individuals with more prolonged recovery are perhaps more capable of quitting smoking successfully. Furthermore, the majority of addiction treatment patients state a preference for treating their alcohol problems before initiating smoking cessation. However, initiating smoking cessation interventions during addictions treatment increases rates of participation in smoking cessation treatment.

We recommend that all smokers in addictions treatment be provided at least a brief smoking cessation intervention, including offering pharmacologic aid to cessation, with encouragement to quit smoking as soon as possible. Especially after smokers in addictions treatment have attained sobriety from alcohol and drugs, it is essential that clinicians clearly advise these patients to quit smoking as soon as possible and provide assistance.

TREATMENT PLANNING

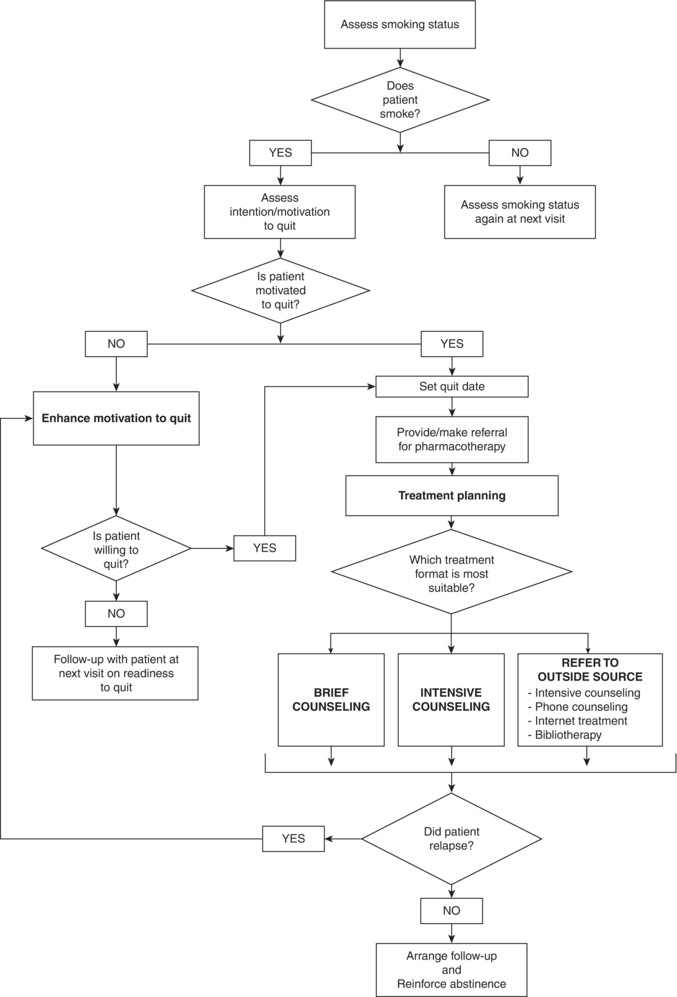

In Figure 59-1, we provide a general schematic for treatment planning for patients who smoke. A simple set of procedures for working with patients who smoke is to follow what has been termed the five As of intervention:

FIGURE 59-1. Schematic for treating cigarette smoking.

- Ask patients whether they use tobacco: All patients should be asked whether or not they have ever smoked, when they last smoked a cigarette, and the typical number of cigarettes they currently smoke per day.

- Advise all patients to quit: Smokers report that physician advice to quit smoking is often an important factor in their deciding to make a quit attempt, and trials have found that brief advice (<3 minutes) by a clinician to quit smoking increases the odds of abstinence by about 30%.

- Assess willingness to make a quit attempt: Patients present with differing levels of motivation for quitting smoking, and intervention should be based on patients’ readiness to change.

- Assist patients in making a quit attempt, as described in the following sections.

- Arrange follow-up contacts to help prevent relapse.

TREATMENT AND TECHNIQUE

Preparing for Quitting

We recommend a “preparation” period before quitting smoking, the length of which can vary according to program needs. There are three key objectives for this period: (1) patients’ motivation to quit and commitment to the program should be clarified and reinforced, (2) patients should self-monitor their daily smoking behavior to begin to learn about their smoking triggers, and (3) a target quit day should be clearly established to allow patients the time to “mentally prepare” and develop coping strategies for quitting smoking.

Motivating Smokers to Quit

Smokers may be ambivalent about the prospect of quitting. This may be especially true of smokers who have failed in prior quit attempts. Acknowledging this ambivalence without directly challenging smokers can help diffuse some of its power to undermine their commitment. A useful and effective method for exploring readiness to change is to have patients rate on a numeric scale (e.g., from 0 to 10) the importance they place on quitting smoking and the confidence they have in successfully quitting. After a patient has provided these ratings, a clinician can inquire further about factors influencing each rating. For example, a clinician might ask, “What made you give a rating of 4 to the importance of quitting rather than a 0?” In this way, the patient is prompted to generate reasons to quit smoking on his or her own. Similarly, exploration of confidence ratings can reveal roadblocks that may prevent more motivated patients from taking action and help identify potential strategies for overcoming these roadblocks.

The challenge is to move smokers from general acceptance of potential negative consequences (“Smoking is dangerous to health.”) to personalized acceptance (“Smoking is dangerous to my health.”). For patients who have low importance ratings, personalized information and feedback can raise awareness of the ways in which smoking is affecting their health. Feedback can take several forms, including evidence of the effects of smoking on the patient’s current physical symptoms (smoker’s cough) and laboratory findings, impact of smoking on disease states, and relationship between smoking and risk. Feedback about the deleterious effects of continued smoking should be paired with feedback about the benefits of cessation. After each piece of information, clinicians should elicit patients’ reactions, answer their questions, and then empathize with and validate their concerns before providing new information. It can also be helpful to have patients write down their specific reasons for both quitting and continuing smoking, as the latter can help patients identify likely barriers to quitting.

For patients who place higher levels of importance on quitting but are not taking action because of a lack of confidence, clinicians can emphasize that it may take several quit attempts before they are finally successful. It is also useful to explore reasons for continued smoking and barriers to quitting so that potential solutions for overcoming barriers can be discussed. Given that the majority of smokers are not willing to quit immediately, it is important that clinicians have modest expectations of whether their patients will make a quit attempt. Smokers who are chronically stuck may benefit from encouragement to take small steps toward action, such as cutting down the number of cigarettes they smoke, delaying their first cigarette of the day, or trying to quit for just 24 hours. The goal of intervention with a patient who is not committed is to move him or her closer to change. Follow-up visits can allow for continued monitoring of readiness and for repeated interventions to enhance motivation and facilitate quitting.

Self-Monitoring of Smoking Behavior

Keeping a written record of cigarettes smoked can help increase knowledge about the factors cueing and maintaining smoking behavior. Self-monitoring also interrupts the automatic smoking habit, encouraging patients to think about every cigarette they smoke and why they smoke it. Often this procedure reduces the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Assessment of mood at the time of each cigarette also can be useful. The situational notations allow patients to identify antecedents that trigger their smoking.

Patients typically find self-monitoring of their smoking behavior inconvenient. It is important that clinicians present the rationale for self-monitoring clearly and follow through at all sessions by reviewing the self-monitoring information with patients to highlight its relevance in their quitting efforts.

Choosing a Quit Date

Central to the quit plan is setting a quit date, ideally within 2 weeks. Setting this date allows smokers to plan for quitting and to obtain the necessary support, which may include the following:

- Telling their family and friends about their quit date

- Making sure that all tobacco products and associated cues, such as ashtrays and cigarette lighters, have been removed

- For those who drink alcohol, avoiding drinking alcohol as much as possible while quitting (alcohol use is involved in about one fourth of all relapses to smoking)

- Thinking about potential triggers for smoking and considering situations in which relapse might be likely to occur

- Reading self-help materials, available through numerous agencies

- Accessing state-funded quitlines, which offer from three to six sessions of proactive counseling

- Pharmacotherapies, including nicotine replacement therapies (gum, inhaler, nasal spray, lozenge, or patch), varenicline, and bupropion SR

Patients should be advised to smoke their last cigarette on the night before their quit date so that they wake up a nonsmoker.

Providers should schedule a specific time to connect immediately with the patient after the quit day to reinforce successes and troubleshoot difficulties in cessation efforts. Follow-up contacts also provide an opportunity to work with patients who have relapsed to smoking. Clinicians can help patients view a relapse as a learning experience that is part of the normal process of quitting and encourage patients to continue their efforts to quit.

CESSATION STAGE INTERVENTIONS

Self-management (sometimes termed self-control or stimulus control) procedures are a critical component of behavioral smoking interventions. Self-management procedures refer to strategies intended to rearrange environmental cues that “trigger” smoking or to alter the consequences of smoking. Using their written smoking records, patients develop a list of trigger situations. They then begin to intervene in these situations to break up the smoking behavior chain (situation—urge—smoke) by using one of three general strategies:

- Avoid the trigger situation: foregoing a coffee break at work with other smokers, leaving the table after dinner, and avoiding social situations involving alcohol

- Alter or change the trigger situation: drinking tea or juice in the morning instead of coffee, watching television in a nonsmoking room, and putting cigarettes in the trunk of the car before driving

- Use an alternative or substitute in place of the cigarette, often in conjunction with avoiding or altering trigger situations or in situations that cannot be avoided or altered: chewing gum, sugarless candy, or cut-up vegetables; toothpicks; relaxation techniques in stressful situations; or activities such as needlework that can keep the hands busy.

Patients should choose strategies that they think will work for them and then try out different approaches, rejecting those that are not useful until they have successfully managed all or most trigger situations without smoking.

Positive social support can be a source of motivation for quitting and has been shown to increase cessation rates. It can also provide positive reinforcement for maintaining abstinence and act as a buffer against stressful life events that might precipitate a relapse. Social support outside of treatment might include making specific requests to friends and family members about steps they can take to support patients’ abstinence efforts.

Because the majority of smokers who initially quit resume smoking within several months of treatment termination, maintenance is a critical issue for smoking cessation programs. The most commonly used behavioral maintenance strategies are based on the relapse prevention model. Preliminary evidence suggests that extending behavioral treatment and pharmacotherapy may improve cessation outcomes.

Relapse prevention theory proposes that the ability to cope with “high-risk” situations for relapse determines an individual’s probability of maintaining abstinence. High-risk situations often involve at least one of the following elements: negative moods, positive moods, social situations involving alcohol, and being in the presence of smokers. To help patients identify high-risk situations, a clinician can ask, “If you were to slip and smoke a cigarette after quit day, in what situation would it be?” For each high-risk situation, patients can develop a set of strategies for managing the situation without smoking. They should be reminded that these high-risk situations are similar to the trigger situations they have previously addressed and that they can apply similar self-management strategies (i.e., avoid, alter, or use an alternative), as well as other problem-solving skills.

When patients experience a slip to smoking, they often progress to further smoking and full relapse. In the event that a slip happens, a few steps can be taken to regain abstinence. First, a slip is an important time for clinicians to assess motivation or commitment to quitting. Has motivation changed or is the patient ambivalent about quitting? Does the patient support the goal of quitting completely or does he or she believe that occasional cigarettes are unlikely to be harmful? If motivation is flagging, then use of the motivational interventions described above is appropriate. If motivation remains high, then it is important for the clinician and the patient to review the circumstances of the slip to better determine why it happened. The lessons learned from the slip are reviewed, and plans for avoiding similar slips in the future can then be made.

A negative addiction such as smoking can be replaced with a “positive addiction” by increasing participation in activities that are incompatible with smoking and are a source of pleasure. Patients are encouraged to set aside time as often as possible (ideally, on a daily basis) for this purpose. It is in this context that we strongly encourage patients to engage in some type of regular physical exercise. Exercise may also be a good alternative to dieting for individuals who are concerned about postcessation weight gain.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Alcohol consumption is the third leading cause of death in the United States, and excessive drinking results in numerous well-documented physical and mental health problems. The combined effects of excessive drinking and smoking are enormous.

A recent clinical trial found that incorporating a brief alcohol intervention into smoking cessation treatment for heavy drinkers who were not alcohol dependent led to significantly lower levels of drinking and increased the odds of smoking abstinence. Steps for brief alcohol intervention include assessing alcohol use and problems, providing clear advice to reduce drinking to those who are drinking excessively, assessing readiness to change drinking patterns, and helping patients set safer drinking goals and make plans for achieving those goals. It is also important to educate patients that any alcohol use, and especially heavy drinking, can greatly increase the odds of a smoking relapse.

Patients with psychiatric comorbidities are twice as likely to smoke as individuals without psychiatric comorbidities. Psychotic disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder are among the most common psychiatric diseases among smokers. Certain clinical characteristics of patients with psychiatric comorbidities and contextual factors present only in psychiatric settings should be taken into account when applying behavioral treatments for smoking.

Patients with psychiatric comorbidities with tobacco dependence are more likely to have sociodemographic risk factors that could lead to poorer smoking outcomes, including being divorced or separated, disabled, uninsured, and having fewer years of education. Those who are smokers also have more comorbid psychiatric disorders, lower global functioning, and poorer psychiatric treatment compliance relative to nonsmoking patients with psychiatric disease. Thus, smokers in the psychiatric setting may be encountering the most severe and complex psychosocial problems of any population. Despite these challenges, severity and chronicity of psychiatric disease do not predict whether or not depressed patients are willing to accept a combined behavioral–pharmacologic nicotine-dependent treatment program, nor does severity predict current motivation to quit smoking.

Another clinical characteristic that may differ in smokers with psychiatric disease is nicotine withdrawal severity. Evidence suggests that smokers with anxiety, depression, and eating disorder symptoms are more likely to experience greater nicotine withdrawal symptoms when discontinuing tobacco use, which in turn suggests that these patients may potentially benefit from assessment and treatment to buffer the effects of nicotine withdrawal. These patients also are more likely to experience cognitive problems because disorders such as major depression and psychosis often present with disturbance in memory, concentration, and thinking. Nonetheless, studies have demonstrated that skill-building and motivational enhancement techniques can be applied to these patients, including those with active psychotic disorders, though modifications should be made to meet the needs of this population.

KEY POINTS

1. A simple set of procedures for working in health care settings with patients who smoke is to follow the five As of intervention: ask patients whether they use tobacco, advise smoking cessation, assess willingness to quit, assist in quitting, and arrange follow-up to prevent relapse.

2. Key elements of behavioral intervention for smoking cessation include: exploring and increasing motivation and readiness to quit, self-monitoring of smoking behavior, choosing a quit date, managing triggers using self-management strategies (avoid, alter, alternative), obtaining social support, identifying and coping with high-risk situations for relapse, managing slips, and making lifestyle changes such as engaging in regular physical exercise.

3. Smoking cessation intervention initiated during treatment for other substance addictions does not harm treatment outcome and may even be associated with better drinking and other substance use outcomes; therefore, all smokers in addictions treatment should be provided at least a brief smoking cessation intervention including offering pharmacologic aid to cessation, with encouragement to quit smoking as soon as possible.

4. Patients with psychiatric comorbidities are more likely to have sociodemographic risk factors that could lead to poorer smoking outcomes and may experience greater nicotine withdrawal upon quitting; nonetheless, studies have demonstrated that skill-building and motivational enhancement techniques can be applied to psychiatric patients.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. The “five As” is a model for brief smoking cessation intervention in health care settings. Which of the following is the correct order of the steps?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree