CHAPTER 1 Basic structure and function of cells

CELL STRUCTURE

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CELLS

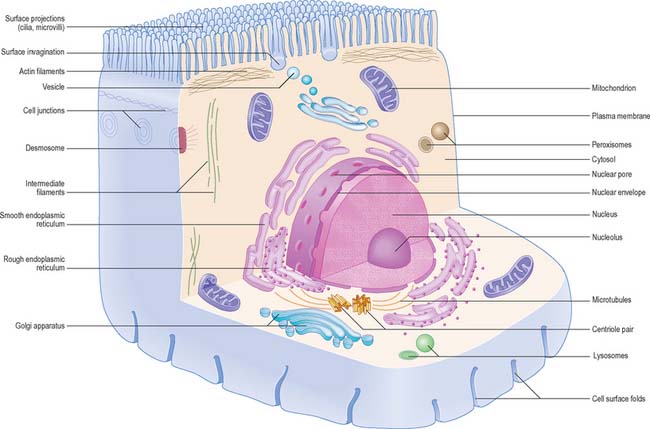

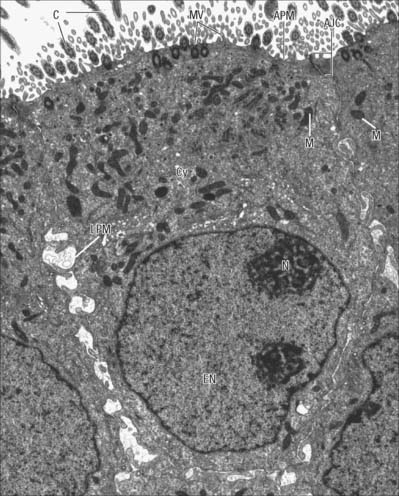

The shapes of mammalian cells vary widely depending on their interactions with each other, their extracellular environment and internal structures. Their surfaces are often highly folded when absorptive or transport functions take place across their boundaries. Cell size is limited by rates of diffusion, either that of material entering or leaving cells, or of diffusion within them. Movement of macromolecules can be much accelerated and also directed by processes of active transport across membranes and by transport mechanisms within the cell. According to the location of absorptive or transport functions, apical microvilli (Fig. 1.1) or basolateral infoldings create a large surface area for transport or diffusion.

CELLULAR ORGANIZATION

Each cell is contained within its limiting plasma, or surface, membrane which encloses the cytoplasm. All cells except mature red blood cells also contain a nucleus that is surrounded by a nuclear membrane or envelope (Fig. 1.1, Fig. 1.2). The nucleus includes the genome of the cell contained within the chromosomes, the nucleolus, and other sub-nuclear organelles. The cytoplasm contains several systems of organelles. These include a series of membrane-bound structures that form separate compartments within the cytoplasm, such as rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, peroxisomes, mitochondria and vesicles for transport, secretion and storage of cellular components. There are also structures that lie free in the non-membranous, cytosolic compartment. They include ribosomes and several filamentous protein networks known collectively as the cytoskeleton. The cytoskeleton determines general cell shape and supports specialized extensions of the cell surface (microvilli, cilia, flagella). It is involved in the assembly of new filamentous organelles (e.g. centrioles) and controls internal movements of the cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vesicles. The cytosol contains many soluble proteins, ions and metabolites.

Cell polarity and domains

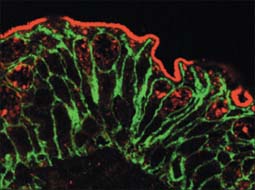

Epithelia (including endothelia and mesothelia) are organized into sheets or more complex structures (see Ch. 2) with very different environments on either side. These cells actively transfer macromolecules and ions between the two surfaces and are thus polarized in structure and function (Fig. 1.3). In polarized cells, particularly in epithelia, the cell is generally subdivided into domains that reflect the polarization of activities within it. The free surface, e.g. that facing the intestinal lumen or airway, is the apical surface, and its adjacent cytoplasm is the apical cell domain. This is where the cell interfaces with a specific body compartment (or, in the case of the epidermis, with the outside world). The apical surface is specialized to act as a barrier, restricting access of substances from this compartment to the rest of the body. Specific components are selectively absorbed from, or added to, the external compartment by the active processes, respectively, of active transport and endocytosis inwardly or exocytosis and secretion outwardly. The apical surface is often covered with small protrusions of the cell surface, microvilli, which increase the surface area, particularly for absorption.

PLASMA MEMBRANE

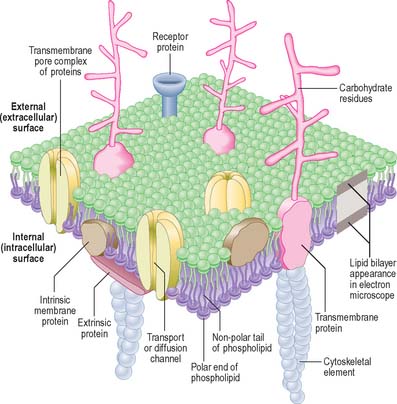

Combinations of biochemical, biophysical and biological techniques have revealed that lipids are not homogenously distributed in membranes, but that some are organized into microdomains in the bilayer, called ‘detergent-resistant membranes’ or lipid ‘rafts’, rich in sphingomyelin and cholesterol (Morris et al 2004). The ability of select subsets of proteins to partition into different lipid microdomains has profound effects on their function, e.g. in T-cell receptor and neurotrophin signalling. The highly organized environment of the domains provides a signalling, trafficking and membrane fusion environment very different from that found in the disorganized fluid mosaic membrane.

In the electron microscope, membranes fixed and contrasted by heavy metals such as osmium appear in section as two densely stained layers separated by an electron-translucent zone – the classic unit membrane (Fig. 1.4). The total thickness is about 5 nm. Freeze-fracture cleavage planes usually pass along the midline of each membrane, where the hydrophobic tails of phospholipids meet. This technique has also demonstrated intramembranous particles embedded in the lipid bilayer; these are in the 5–15 nm range and in most cases represent large transmembrane protein molecules or complexes of molecules. Intramembranous particles are distributed asymmetrically between the two half-membranes, usually adhering more to one face than to the other. In plasma membranes, the inner or protoplasmic (cytoplasmic) half-membrane carries most particles, seen on its surface facing the exterior (the P face). Where they have been identified, particles usually represent channels for the transmembrane passage of ions or molecules.

The cell coat (glycocalyx)

The plasma membrane differs structurally from internal membranes in that it possesses an external, diffuse, carbohydrate-rich coat, the cell coat or glycocalyx. The cell coat forms an integral part of the plasma membrane, projecting as a diffusely filamentous layer 2–20 nm or more from the lipoprotein surface (see Fig. 1.5). The overall thickness of the plasma membrane is therefore variable, but is typically 8–10 nm. The cell coat is composed of the carbohydrate portions of glycoproteins and glycolipids embedded in the plasma membrane (Fig. 1.4).

Cell surface contacts

The plasma membrane is the surface which establishes contact with other cells and with structural components of extracellular matrices. These contacts may have a predominantly adhesive role, or initiate instructive signals within and between cells, or both; they frequently affect the behaviour of cells. Structurally, there are two main classes of contact, both associated with cell adhesion molecules. One class is associated with specializations at discrete regions of the cell surface that are ultrastructurally distinct. These are described on page 6. The second, general, class of adhesive contact has no obvious associated ultrastructural features.

General adhesive contacts

Calcium-dependent adhesion molecules

Cadherins, selectins and integrins are calcium-dependent adhesion molecules. Cadherins are transmembrane proteins, with five heavily glycosylated external domains. They are responsible for strong general intercellular adhesion, as well as being components of some specialized adhesive contacts, and are attached by linker proteins (catenins) at their cytoplasmic ends to underlying cytoskeletal fibres (either actin or intermediate filaments). Different cell types possess different members of the cadherin family, e.g. N-cadherins in nervous tissue, E-cadherins in epithelia, and P-cadherins in the placenta. These molecules bind to those of the same type in other cells (homophilic binding), so that cells of the same class adhere to each other preferentially, forming tissue aggregates or layers, as in epithelia. For a review of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis, see Gumbiner (2005).

Selectins are found on leukocytes, platelets and vascular endothelial cells. They are transmembrane lectin glycoproteins that can bind with low affinity to the carbohydrate groups on other cell surfaces to permit movement between the two, e.g. the rolling adhesion of leukocytes on the walls of blood vessels (p. 136). They function cooperatively in sequence with integrins, which strengthen the selectin adhesion.

Calcium-independent adhesion molecules

The best known calcium-independent adhesion molecules are glycoproteins that have external domains related to immunoglobulin molecules. Most are transmembrane proteins. Some are entirely external, either attached to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, or secreted as soluble components of the extracellular matrix. Different types are expressed in different tissues. Neural cell adhesion molecules (N-CAMs) are found on a number of cell types, but are expressed widely by neural cells. Intercellular adhesion molecules (I-CAMs) are expressed on vascular endothelial cells. Cell adhesion molecule binding is predominantly homophilic, although some use a heterophilic mechanism, e.g. vascular intercellular adhesion molecule (VCAM), which can bind to integrins.

For further information on all aspects of cell adhesion molecules and intercellular contacts, see Pollard & Earnshaw (2007).

Specialized adhesive contacts

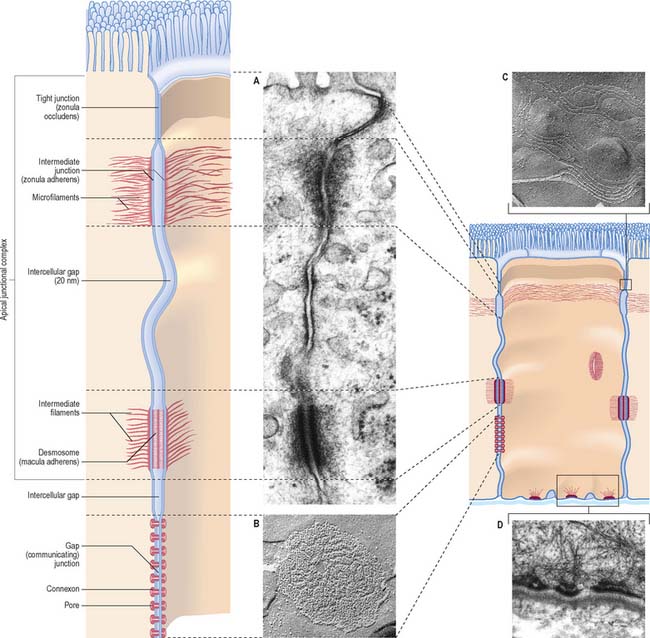

Specialized adhesive contacts, some of which mediate activities other than simple mechanical cohesion, are localized regions of the cell surface with particular ultrastructural characteristics. Three major classes exist: occluding, adhesive and communicating junctions (Fig. 1.5).

Occluding junctions (tight junctions, zonula occludens)

Occluding junctions create diffusion barriers in continuous layers of cells, including epithelia, mesothelia and endothelia, and prevent the passage of materials across the cellular layer through intercellular spaces. They form a continuous belt (zonula) around the cell perimeter, near the apical surface in cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells. At a tight junction, the membranes of the adjacent cells come into contact, so that the gap between them is obliterated. Freeze-fracture electron microscopy shows that the contacts between the membranes lie along branching and anastomosing ridges formed by the incorporation of chains of intramembranous protein particles on the P face of the lipid bilayer (Fig. 1.5C).

This arrangement ensures that substances can only pass through the layer of cells by diffusion or transport through their apical membranes and cytoplasm. The cells thus selectively modify the environment on either side of the layer. Occluding junctions also create regional differences in the plasma membranes of the cells in which they are found. For example, in epithelia, the composition of the apical plasma membrane differs from that of the basolateral regions (see Fig. 1.3), and this allows these regions to engage in functions such as directional transport of ions and uptake of macromolecules. Because tight junctions have high concentrations of fixed transmembrane proteins, they act as barriers to lateral diffusion of lipid and protein within membranes. The integrity of tight junctions is calcium-dependent. Cells can transiently alter the permeability of their tight junctions to increase passive paracellular transport in some circumstances.

Adhesive junctions

Desmosomes (maculae adherentes)

Desmosomes are limited, plaque-like areas of particularly strong intercellular contact. They can be located anywhere on the cell surface. In epithelial cells, there may be a circumferential row of desmosomes parallel to the tight and intermediate junctional zones, an arrangement that forms the third, most basally situated, component of the epithelial apical junctional complex (Fig. 1.5). The intercellular gap is approximately 25 nm, is filled with electron-dense filamentous material running transversely across it and is also marked by a series of densely staining bands running parallel to the cell surfaces. Adhesion is mediated by calcium-dependent cadherins, desmoglein and desmocollin. Within the cells on either side, a cytoplasmic density underlies the plasma membrane and includes the anchor proteins desmoplakin and plakoglobin, into which the ends of intermediate filaments are inserted. The type of intermediate filament depends on cell type, e.g. keratins are found in epithelia and desmin filaments in cardiac muscle cells. Desmosomes form strong anchorage points, likened to spot-welds, between cells subject to mechanical stress, e.g. in the prickle cell layer of the epidermis, where they are extremely numerous and large.

Hemidesmosomes

Hemidesmosomes are best known as anchoring junctions between the bases of epithelial cells and the basal lamina. Ultrastructurally, they resemble a single-sided desmosome, anchored on one side to the plasma membrane, and on the other to the basal lamina and adjacent collagen fibrils (Fig. 1.5D and see Fig. 7.5). On the cytoplasmic side of the membrane there is a dense plaque into which keratin filaments are inserted. Hemidesmosomes use integrins as their adhesion molecules, whereas desmosomes use cadherins.

Gap junctions (communicating junctions)

Gap junctions resemble tight junctions in transverse section, but the two apposed lipid bilayers are separated by an apparent gap of 3 nm which is bridged by numerous transmembrane channels (connexons). Connexons are formed by a ring of six connexin proteins in each membrane. Their external surfaces meet those of the adjacent cell in the middle. A minute central pore links one cell to the next (Fig. 1.5). These channels may exist in small numbers, and this makes them difficult to detect structurally. However, they lower the transcellular electrical resistance and so can be detected by microelectrodes. Larger assemblies of many thousands of channels are often packed in hexagonal arrays (Fig. 1.5B). Such junctions form limited attachment plaques rather than continuous zones, and so allow free passage of substances within the adjacent intercellular space, unlike tight junctions. They occur in numerous tissues including the liver, epidermis, pancreatic islet cells, connective tissues, cardiac muscle and smooth muscle, and are also common in embryonic tissues. In the central nervous system, they are found in the ependyma and between neuroglial cells, and they form electrical synapses between some types of neurone, although this is rare in humans. Very recently, a second family of gap junctional proteins has been discovered, the pannexins. In humans, expression of pannexins has been most extensively studied in the nervous system (reviewed in Litvin et al 2006).

Other types of junction

Chemical synapses and neuromuscular junctions are specialized areas of intercellular adhesion where neurotransmitters secreted from a neuronal terminal gain access to specialized receptor molecules on a recipient cell surface. They are described on pages 44 and 62, respectively.

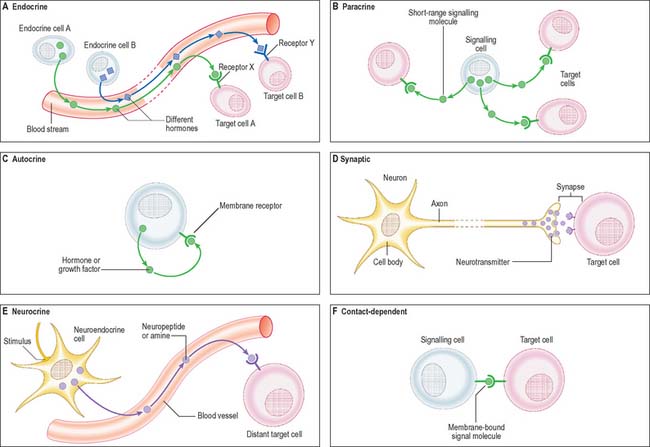

Cell signalling

The signal may act over a long distance, e.g. endocrine signalling through the release of hormones into the bloodstream, or neuronal synaptic signalling via electrical impulse transmission along axons and subsequent release of chemical transmitters of the signal at synapses (p. 44) or neuromuscular junctions (p. 62). A specialized variation of endocrine signalling (neurocrine or neuroendocrine signalling) occurs when neurones or paraneurones (e.g. chromaffin cells of the suprarenal medulla) secrete a hormone into interstitial fluid and the bloodstream.

These different types of intercellular signalling mechanism are illustrated in Figure 1.6. For further reading, see Alberts et al (2002) and Pollard & Earnshaw (2007).

Signalling molecules and their receptors

The majority of signalling molecules (ligands) are hydrophilic. They cannot cross the plasma membrane of a recipient cell to effect changes intracellularly unless they first bind to a plasma membrane receptor protein. Ligands are mainly proteins (usually glycoproteins), polypeptides or highly charged biogenic amines. They include: classic peptide hormones of the endocrine system; cytokines, which are mainly of haemopoietic cell origin and involved in inflammatory responses and tissue remodelling (e.g. the interferons, interleukins, tumour necrosis factor, leukaemia inhibitory factor); polypeptide growth factors (e.g. the epidermal growth factor superfamily, nerve growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, the fibroblast growth factor family, transforming growth factor beta and the insulin-like growth factors). Polypeptide growth factors are multifunctional molecules with more widespread actions and cellular sources than their names suggest. They and their receptors are commonly mutated or aberrantly expressed in certain cancers. The cancer-causing gene variant is termed a transforming oncogene and the normal (wild-type) version of the gene is a cellular oncogene or proto-oncogene. The activated receptor acts as a transducer to generate intracellular signals, which are either small diffusible second messengers (e.g. calcium, cyclic adenosine monophosphate or the plasma membrane lipid-soluble diacylglycerol), or larger protein complexes that amplify and relay the signal to target control systems. For further reading on growth factors and other signalling molecules, see Epstein (2003).

Receptor proteins

Cell surface receptor proteins are generally grouped according to their linkage to one of three intracellular systems: ion channel-linked receptors; G-protein-coupled receptors; receptors that link to enzyme systems. Other receptors do not fit neatly into any of these categories. All the known G-protein-coupled receptors belong to a structural group of proteins that pass through the membrane seven times in a series of serpentine loops. These receptors are thus known as seven-pass transmembrane receptors or, because the transmembrane regions are formed from α-helical domains, as seven-helix receptors. The most well-known of this large group of phylogenetically ancient receptors are the odorant-binding proteins of the olfactory system, the light-sensitive receptor protein, rhodopsin, and many of the receptors for clinically useful drugs. A comprehensive list of receptor proteins, their activating ligands and examples of the resultant biological function, is given in Pollard & Earnshaw (2007).

Intracellular signalling

A wide variety of small molecules carry signals within cells, conveying the signal from its source (e.g. activated plasma membrane receptor) to its target (e.g. the nucleus). These second messengers convey signals as fluctuations in local concentration, according to rates of synthesis and degradation by specific enzymes (e.g. cyclases involved in cyclic nucleotide (cAMP, cGMP) synthesis), or, in the case of calcium, according to the activities of calcium channels and pumps. Other, lipidic, second messengers such as phosphatidylinositol, derive from membranes and may act within the membrane to generate downstream effects. For further consideration of the complexity of intracellular signalling pathways, see Pollard & Earnshaw (2007).

Exocytosis and endocytosis

The process of endocytosis involves the internalization of vesicles derived from the plasma membrane. The vesicles may contain: engulfed fluids and solutes from the extracellular interstitial fluid (pinocytosis); larger macromolecules, often bound to surface receptors (receptor-mediated endocytosis); particulate matter, including microorganisms or cellular debris (phagocytosis). Pinocytosis generally involves small fluid-filled vesicles and is a marked property of capillary endothelium, e.g. where vesicles containing nutrients and oxygen dissolved in blood plasma are transported from the vascular lumen to the endothelial basal plasma membrane (see Fig. 6.11). Interstitial fluid containing dissolved carbon dioxide is also taken up by pinocytosis for simultaneous transportation across the endothelial cell wall in the opposite direction, for release into the bloodstream by exocytosis. This shuttling of pinocytotic vesicles is also termed transcytosis. Larger volumes of fluid are engulfed by dendritic cells, e.g. in the process of sampling interstitial fluids by macropinocytosis in immune surveillance for antigens (p. 79). Interstitial fluid is inevitably taken up during receptor-mediated endocytosis when ligands are internalized.

Receptor-mediated endocytosis, also known as clathrin-dependent endocytosis, is initiated at specialized regions of the plasma membrane known as clathrin-coated pits. Clathrin is a protein that cross-links adjacent adaptor protein (adaptin) complexes to form a basket-like structure, bending the membrane inwards into a hemisphere. Much, but not all, fluid-phase pinocytosis also utilizes clathrin-coated pits. Ligands such as the iron-transporting protein, transferrin, and the cholesterol-transporting low-density lipoprotein bind to their receptors, which cluster in clathrin-coated pits through an interaction with adaptins. The pits then invaginate and pinch off from the plasma membrane, internalizing both receptor and ligand. The processing of endocytic vesicles and their contents is described on p. 12. For further details of the molecular mechanisms of endocytosis, see Alberts et al (2002) or Pollard & Earnshaw (2007).

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis is a property of many cell types, but is most efficient in cells specialized for this activity. The professional phagocytes of the body belong to the monocyte lineage of haemopoietic cells, in particular the tissue macrophages (p. 78). Other effective phagocytes are neutrophil granulocytes and most dendritic cells (p. 79), which are also of haemopoietic origin. Phagocytosis plays an important part in the immune defence system of the body, in which the amoeboid process of ingestion of organisms for nutrition has evolved into a mechanism for the clearance of microorganisms invading the body. Macrophages also ingest particulate material including inorganic matter, such as inhaled dust particles, in addition to debris from dead cells and protein aggregates such as immune complexes in the blood, airways, interstitial spaces and connective tissue matrices.

CYTOPLASM

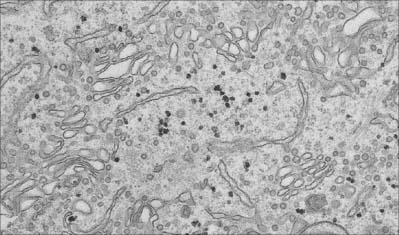

Endoplasmic reticulum

Endoplasmic reticulum is a system of interconnecting membrane-lined channels within the cytoplasm (Fig. 1.7). These channels take various forms, including cisternae (flattened sacs), tubules and vesicles. The membranes divide the cytoplasm into two major compartments. The intramembranous compartment includes the space where secretory products are stored or transported to the Golgi complex and cell exterior. The extramembranous cytosol is made up of the colloidal proteins such as enzymes, carbohydrates and small protein molecules, together with ribosomes and ribonucleic acids, and elements of the cytoskeleton.

Fig. 1.7 Smooth endoplasmic reticulum with associated vesicles. The dense particles are glycogen granules.

(By courtesy of Rose Watson, Cancer Research UK.)

Structurally, the channel system can be divided into rough or granular endoplasmic reticulum, which has ribosomes attached to its outer cytosolic surface, and smooth or agranular endoplasmic reticulum, which lacks ribosomes. Functionally, the endoplasmic reticulum is compartmentalized into specialized regions with unique functions. For further reading see Levine & Rabouille (2005).