Chapter 1 Basic Principles and Pharmacodynamics

Drug Nomenclature

Trade, Brand, or Proprietary Name

Clinical Connection: Drugs can have many different names. For example, a prototypical calcium channel blocker of the dihydropyridine class has the chemical name 3,5-dimethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate, the generic name nifedipine, and is available in the United States under several trade names including Adalat, Nifedical, and Procardia. Although marketing emphasizes trade names, the use of generic drug names is encouraged in practice to reduce prescribing errors and offers the opportunity for substitutions if appropriate.

Clinical Connection: Drugs can have many different names. For example, a prototypical calcium channel blocker of the dihydropyridine class has the chemical name 3,5-dimethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate, the generic name nifedipine, and is available in the United States under several trade names including Adalat, Nifedical, and Procardia. Although marketing emphasizes trade names, the use of generic drug names is encouraged in practice to reduce prescribing errors and offers the opportunity for substitutions if appropriate.Drug-Receptor Interactions

Although some notable exceptions exist, a fundamental principle of pharmacology is that drugs must interact with a molecular target to exert an effect. Drug interaction with molecular targets is the initiating event in a multistep process that ultimately alters tissue function. For the purposes of current discussion, the target will be referred to as a receptor. An in-depth discussion of molecular targets and a description of these processes will be presented later in this chapter (see the discussion of molecular mechanisms of drug action). Let us first consider the relationship between drug binding to its target receptors and the ultimate response of the tissue.

A minimum number of drug receptor complexes must be formed for a response to be initiated (threshold)

A minimum number of drug receptor complexes must be formed for a response to be initiated (threshold) As drug concentration increases, the number of drug-receptor complexes increases and drug effect increases

As drug concentration increases, the number of drug-receptor complexes increases and drug effect increases A point will be reached at which all receptors are bound to drug, and therefore no further drug-receptor complexes can be formed and the response does not increase any further (saturation)

A point will be reached at which all receptors are bound to drug, and therefore no further drug-receptor complexes can be formed and the response does not increase any further (saturation)Law of Mass Action Applied to Drugs

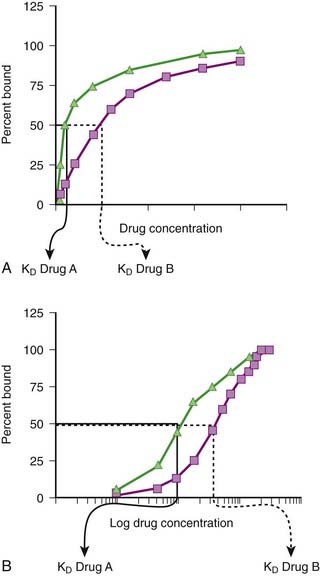

Although the amount of drug receptor-complex formed is proportional to the concentrations of drug and receptor, this relationship is not linear but is in fact parabolic (Figure 1-1, A). Accordingly, this relationship is most often diagrammed on a semilogarithmic graph to linearize the relationship and encompass the large range of concentrations typical of the drug-receptor relationship (Figure 1-1, B).

Factors Affecting Drug-Target Interactions

Drug Binding

It is important to recognize that, in most cases, binding of drug to target molecules involves weaker bonds. Accordingly, the drug-receptor complex is not static, but rather there is continuous association and dissociation of the drug with the receptor as long as drug is present. A measure of the relative ease with which the association and dissociation reactions occur is the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD). Each drug-receptor combination will have a characteristic KD value. Drugs with high affinity for a given receptor display a small value for KD, and vice versa. In Figure 1-1, A and B, Drug A has a higher affinity for the receptor than Drug B. KD also represents the concentration of drug needed to bind 50% of the total receptor population. These concepts are important in the study of basic pharmacologic data regarding different compounds with affinity for the same receptor. In general, drugs with lower KD values will require lower concentrations to achieve sufficient receptor occupancy to exert an effect.

Selectivity of Drug Responses

The cell will respond only to the spectrum of drugs that exhibit affinity for the receptors expressed by the cell.

The cell will respond only to the spectrum of drugs that exhibit affinity for the receptors expressed by the cell. The greater the extent to which a drug molecule exhibits high affinity for only one receptor, the more selective will be the drug’s actions, with lower potential for side effects.

The greater the extent to which a drug molecule exhibits high affinity for only one receptor, the more selective will be the drug’s actions, with lower potential for side effects. The higher the affinity and efficacy of a given drug, the smaller the amount of drug necessary to activate a critical mass of drug receptors to effect a tissue response, and the lower the potential for nonselective actions.

The higher the affinity and efficacy of a given drug, the smaller the amount of drug necessary to activate a critical mass of drug receptors to effect a tissue response, and the lower the potential for nonselective actions. Clinical Connection: β-Adrenergic receptor antagonists are effective drugs for a number of cardiovascular disorders. Some β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are selective for β1-adrenergic receptors to limit the potential for bronchoconstriction caused by blocking β2-adrenergic receptors. However, even β1-selective antagonists must be used cautiously in asthmatic patients, particularly at higher doses, to avoid further impairment of airway function in these patients.

Clinical Connection: β-Adrenergic receptor antagonists are effective drugs for a number of cardiovascular disorders. Some β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are selective for β1-adrenergic receptors to limit the potential for bronchoconstriction caused by blocking β2-adrenergic receptors. However, even β1-selective antagonists must be used cautiously in asthmatic patients, particularly at higher doses, to avoid further impairment of airway function in these patients.Tissue Distribution of Receptors

The more restricted the distribution of drug receptor, the more selective will be the effects of drugs that interact with that receptor.

The more restricted the distribution of drug receptor, the more selective will be the effects of drugs that interact with that receptor. Clinical Connection: Knowledge of receptor subtypes and their regional distribution can assist in drug selection. A useful example is the use of α-adrenergic receptor antagonists for the treatment of urinary retention secondary to prostatic hypertrophy. Nonselective α-adrenergic antagonists are not routinely used to treat urinary retention in men with prostatic hypertrophy, because although they block α receptors in the prostate and improve urine flow, they also block α receptors in blood vessels and cause hypotension. The prostate expresses primarily α1B-adrenergic receptors, whereas blood vessels express other subtypes. Consequently, drugs such as tamsulosin that are selective for the α1B subtype expressed primarily in the prostate are much more useful in the treatment of prostatic hypertrophy.

Clinical Connection: Knowledge of receptor subtypes and their regional distribution can assist in drug selection. A useful example is the use of α-adrenergic receptor antagonists for the treatment of urinary retention secondary to prostatic hypertrophy. Nonselective α-adrenergic antagonists are not routinely used to treat urinary retention in men with prostatic hypertrophy, because although they block α receptors in the prostate and improve urine flow, they also block α receptors in blood vessels and cause hypotension. The prostate expresses primarily α1B-adrenergic receptors, whereas blood vessels express other subtypes. Consequently, drugs such as tamsulosin that are selective for the α1B subtype expressed primarily in the prostate are much more useful in the treatment of prostatic hypertrophy.Activation of the Molecular Target

Agonists (sometimes called full agonists) produce maximum activation of the receptor and elicit a maximum response from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 1.

Agonists (sometimes called full agonists) produce maximum activation of the receptor and elicit a maximum response from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 1. Antagonists bind but produce no activation of the receptor and therefore block responses from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 0.

Antagonists bind but produce no activation of the receptor and therefore block responses from the tissue. They are assigned an intrinsic activity of 0. Partial agonists exhibit intrinsic activity between 0 and 1. Partial agonists produce weaker activation of the receptor than full agonists or the endogenous ligand. Partial agonists produce only partial activation of the receptor and its downstream signaling events. The clinical effect of a partial agonist will depend on its intrinsic activity and the concentration of the endogenous ligand. If concentrations of the endogenous ligand are really low, then a partial agonist will increase receptor activation, functioning as a weak agonist. In contrast, if concentrations of endogenous ligand are high, the partial agonist will compete for receptors and bind to a certain proportion of receptors previously bound by endogenous ligand. Because the partial agonist produces weaker activation of the receptor than endogenous ligand, the net effect will be less cumulative receptor activation. This will produce inhibition of the response mediated by the endogenous ligand, and the partial agonist will act as a weak antagonist.

Partial agonists exhibit intrinsic activity between 0 and 1. Partial agonists produce weaker activation of the receptor than full agonists or the endogenous ligand. Partial agonists produce only partial activation of the receptor and its downstream signaling events. The clinical effect of a partial agonist will depend on its intrinsic activity and the concentration of the endogenous ligand. If concentrations of the endogenous ligand are really low, then a partial agonist will increase receptor activation, functioning as a weak agonist. In contrast, if concentrations of endogenous ligand are high, the partial agonist will compete for receptors and bind to a certain proportion of receptors previously bound by endogenous ligand. Because the partial agonist produces weaker activation of the receptor than endogenous ligand, the net effect will be less cumulative receptor activation. This will produce inhibition of the response mediated by the endogenous ligand, and the partial agonist will act as a weak antagonist. Inverse agonists inhibit rather than activate the receptor. This phenomenon is evident with receptors that exhibit baseline (ongoing or constitutive) activity in the absence of agonist binding. In these cases, binding of the inverse agonist reduces the baseline activity of the receptor, which in turn elicits an effect opposite that of binding of the agonist. Inverse agonists and antagonists will elicit similar effects because both types of drugs will reverse the effects of endogenous ligands. Many clinically used antagonists may in fact be inverse agonists. Inverse agonists may assume particular clinical importance in disease states in which constitutive activity of receptors plays an important role. Increasing evidence suggests that a number of diseases are a result of gain of function mutations at the receptor that result in constitutive activity of the receptor in the absence of agonist.

Inverse agonists inhibit rather than activate the receptor. This phenomenon is evident with receptors that exhibit baseline (ongoing or constitutive) activity in the absence of agonist binding. In these cases, binding of the inverse agonist reduces the baseline activity of the receptor, which in turn elicits an effect opposite that of binding of the agonist. Inverse agonists and antagonists will elicit similar effects because both types of drugs will reverse the effects of endogenous ligands. Many clinically used antagonists may in fact be inverse agonists. Inverse agonists may assume particular clinical importance in disease states in which constitutive activity of receptors plays an important role. Increasing evidence suggests that a number of diseases are a result of gain of function mutations at the receptor that result in constitutive activity of the receptor in the absence of agonist. Clinical Connection: Drugs that act as inverse agonists may have important clinical applications for diseases in which receptors are activated in the absence of endogenous agonist. One example is in cancer chemotherapy. In a number of human cancers, mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor cause the receptor to be active in the absence of epidermal growth factor. In this setting, a traditional antagonist would be of no benefit. However, drugs that act as inverse agonists at the epidermal growth factor would suppress receptor activation and reduce the growth signaling via this pathway. Epidermal growth factor inverse agonists are being studied as cancer chemotherapy drugs.

Clinical Connection: Drugs that act as inverse agonists may have important clinical applications for diseases in which receptors are activated in the absence of endogenous agonist. One example is in cancer chemotherapy. In a number of human cancers, mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor cause the receptor to be active in the absence of epidermal growth factor. In this setting, a traditional antagonist would be of no benefit. However, drugs that act as inverse agonists at the epidermal growth factor would suppress receptor activation and reduce the growth signaling via this pathway. Epidermal growth factor inverse agonists are being studied as cancer chemotherapy drugs.Quantifying Drug-Target Interactions: Dose-Response Relationships

Graded Dose-Response Curves

Measure an effect that is continuous such that, in theory, any value is possible in a given range (0% through 100%).

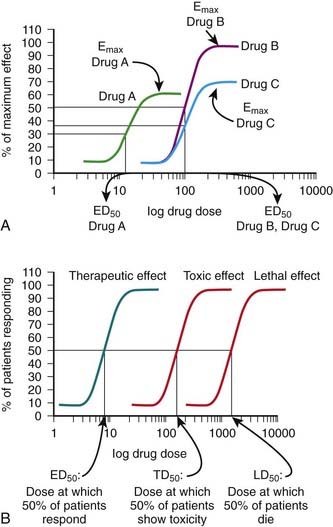

Measure an effect that is continuous such that, in theory, any value is possible in a given range (0% through 100%). Have a sigmoidal shape similar to the drug receptor occupancy curves shown in Figure 1-2, because the biologic response to a drug is determined by the interaction of a drug with a receptor or molecular target.

Have a sigmoidal shape similar to the drug receptor occupancy curves shown in Figure 1-2, because the biologic response to a drug is determined by the interaction of a drug with a receptor or molecular target. Exhibit a dose beyond which no further response is achieved (maximal effect; Emax). Emax is a measure of the pharmacologic efficacy of the drug.

Exhibit a dose beyond which no further response is achieved (maximal effect; Emax). Emax is a measure of the pharmacologic efficacy of the drug.The ED50 and Emax are useful parameters to assess drugs. In Figure 1-2, A, Drug A is more potent than Drug B or Drug C, whereas Drugs B and C have equal potency. Potency is sometimes used incorrectly as a measure of therapeutic effectiveness. In fact, in most cases potency is secondary to Emax in drug selection. However, in situations in which the absorption of drug is very poor, such that only small quantities of the drug reach the target, potency can be a critical consideration. Drugs with higher Emax values have higher pharmacologic efficacy.

In Figure 1-2, A, Drug B has the greatest efficacy, followed by Drug C, whereas Drug A, despite being the most potent, has the least efficacy. Drug C is equipotent with Drug B but has less efficacy. Thus, potency and efficacy can vary independently. It is important not to confuse the pharmacologic usage of efficacy with the more general usage. Pharmacologic efficacy is a measure of the strength of effect produced by the maximum dose of drug. By definition, antagonists do not activate their receptors after binding and therefore have an intrinsic activity and efficacy of 0. Nevertheless, an antagonist may be very clinically “efficacious” or beneficial because it blocks activation of the receptor by endogenous agonist.

Quantal Dose-Response Curves

Quantal dose-response curves do the following:

Describe the relationship between drug dosage and the frequency with which a biologic effect occurs. For example, in individuals administered an anticonvulsant medication, the percentage of individuals not experiencing a convulsive episode at any given dose is plotted in cumulative fashion (Figure 1-2, B).

Describe the relationship between drug dosage and the frequency with which a biologic effect occurs. For example, in individuals administered an anticonvulsant medication, the percentage of individuals not experiencing a convulsive episode at any given dose is plotted in cumulative fashion (Figure 1-2, B). Represent a cumulative frequency distribution for a given response.

Represent a cumulative frequency distribution for a given response. Provide an ED50 value that reflects the dose of drug that produces a response in 50% of the population (also called the median effective dose).

Provide an ED50 value that reflects the dose of drug that produces a response in 50% of the population (also called the median effective dose). Provide an estimate of the variability in response of the patient population to the drug. A steep slope indicates that all the patients respond in a narrow range of doses, whereas a shallow slope indicates considerable variability in the ability of the drug to elicit a response in the patient population.

Provide an estimate of the variability in response of the patient population to the drug. A steep slope indicates that all the patients respond in a narrow range of doses, whereas a shallow slope indicates considerable variability in the ability of the drug to elicit a response in the patient population. Can be constructed for a graded or continuous response by choosing a target magnitude of response (e.g., blood pressure reduction of 20 mm Hg) and plotting the proportion of patients that achieves this magnitude of response at each increase in dosage. This type of information can be useful in determining a starting dosage to achieve a given level of effect

Can be constructed for a graded or continuous response by choosing a target magnitude of response (e.g., blood pressure reduction of 20 mm Hg) and plotting the proportion of patients that achieves this magnitude of response at each increase in dosage. This type of information can be useful in determining a starting dosage to achieve a given level of effect Can be plotted for therapeutic, toxic, and lethal effects to obtain:

Can be plotted for therapeutic, toxic, and lethal effects to obtain: