Bacteria

Bacterial pneumonia may be primary within the lung or may be secondary to hematogenous dissemination from bacterial infection at another site. The virulence of the bacteria, host immunity, and other factors determine the pathology of bacterial pneumonias.

Part 1 Pseudomonas

Alvaro C. Laga

Abida K. Haque

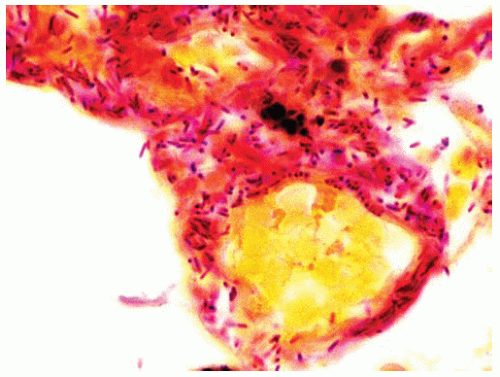

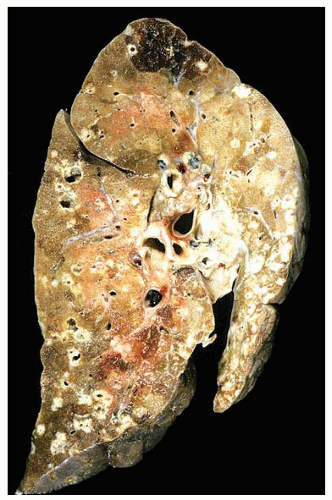

Pseudomonas sp. are gram-negative bacilli. They tend to be thin and long compared to the shorter, fatter Enterobacteriaceae. P. aeruginosa is the most virulent species of the genus and the predominant isolate in clinical laboratories. This microorganism produces powerful exoenzymes, including proteases and elastases that result in tissue destruction. Consequently, the hallmarks of Pseudomonas infection are hemorrhage, necrosis, and abscess formation. It may cause pneumonia by two different mechanisms: (i) aspiration of oral contents in the nosocomial setting, when patients change the oral flora to gram-negative species, and (ii) secondary spread to the lungs from distant foci through the bloodstream. Macroscopic lesions may present as firm, yellow-brown or tan necrotic nodules, often sharply delimited from the surrounding tissue.

Histologic Features

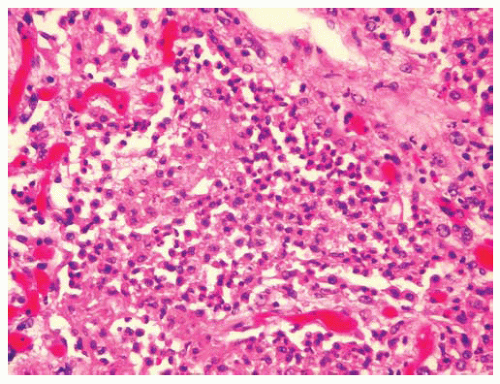

Mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.

Necrosis, vasculitis, and abscess formation can often be seen.

Gram-negative bacilli may be observed on the adventitial surface of blood vessels.

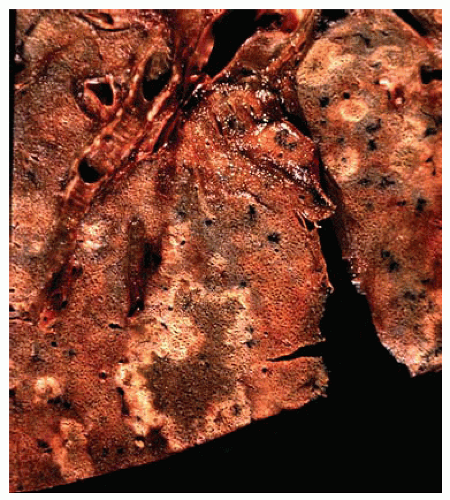

Figure 97.1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Multiple well-defined yellow-brown nodules within the lung parenchyma are seen in this case. |

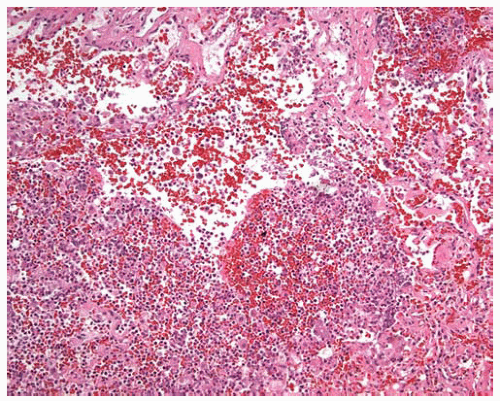

Figure 97.2 Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Intense inflammatory infiltrate with destruction of alveolar septa and hemorrhage. |

Part 2 Klebsiella Pneumonia

Abida K. Haque

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a gram-negative, nonmotile bacillus approximately 6 μm in length and 0.6 μm in width, and an important component of normal gastrointestinal flora. K. pneumoniae is also an important cause of community-acquired pneumonia, particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Histologic Features

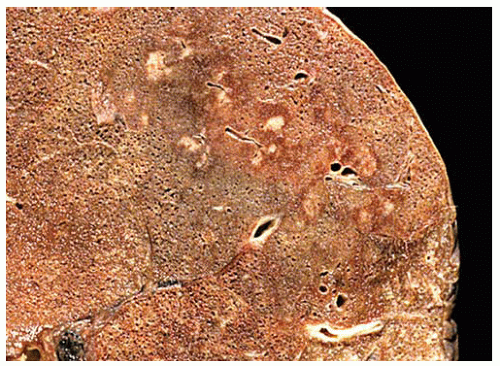

The acute pneumonia may be patchy or lobar; although there is consolidation in early stages, the later stages are associated with necrosis and abscess formation.

Neutrophil infiltrates fill the alveoli in the acute stage, followed later by macrophages.

Healing is often associated with formation of scars.

The bacilli have a polysaccharide mucoid capsule, giving rise to mucoid colonies on agar, and a mucoid/gelatinous appearance to the consolidated areas.

The bacilli are blackened and easily visible with silver stains (Gomori methenamine silver [GMS]).

Pulmonary gangrene is a rare complication.

Figure 97.4 Gross figure shows areas of bronchopneumonia with a gelatinous center and pale tan borders due to the mucoid exudate produced by K. pneumoniae capsules. |

Part 3 Staphylococcus

Abida K. Haque

Staphylococci colonize the skin, anterior nasal cavity, and sometimes the gastrointestinal tract of healthy individuals, resulting in 20% to 40% of the population becoming a carrier. Staphylococcal pneumonia may result from aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions or as a complication of viral pneumonia. The characteristic feature of infection is early necrosis and abscess formation, which may extend to the pleura, resulting in empyema.

Histologic Features

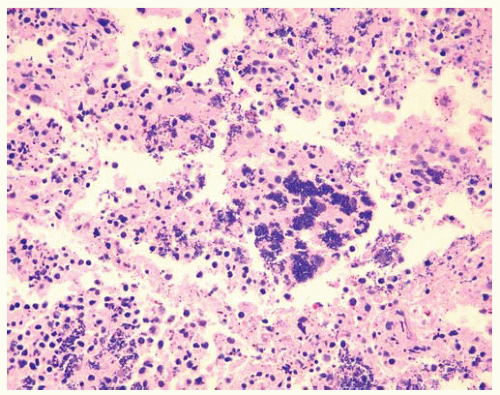

The abscess contains clusters of hematoxyphil-staining, gram-positive bacteria, often in clusters.

The bacterial colonies may be surrounded by an acellular eosinophilic matrix rich in immunoglobulins (Splendore-Hoeppli phenomena), also called a botryomycotic abscess.

Figure 97.8 Clusters of hematoxyphil-staining bacteria within inflammatory infiltrate in alveolar spaces.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|