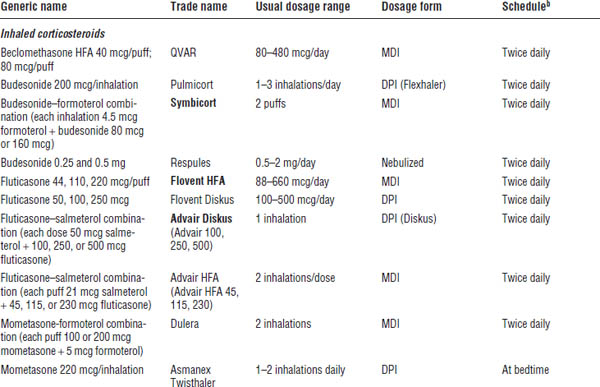

Figure 32-1. Classification of Asthma Severity (Children ≥ 12 Years of Age and Adults)

Key: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICU, intensive care unit

Notes:

■ The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decisionmaking required to meet individual patient needs.

■ Level of severity is determined by assessment of both impairment and risk. Assess impairment domain by patient’s/caregiver’s recall of previous 2–4 weeks and spirometry. Assign severity to the most severe category in which any feature occurs.

■ At present, there are inadequate data to correspond frequencies of exacerbations with different levels of asthma severity. In general, more frequent and intense exacerbations (e.g., requiring urgent, unscheduled care, hospitalization, or ICU admission) indicate greater underlying disease severity. For treatment purposes, patients who had 2 exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma.

Reproduced from NIH Expert Panel Report 3.

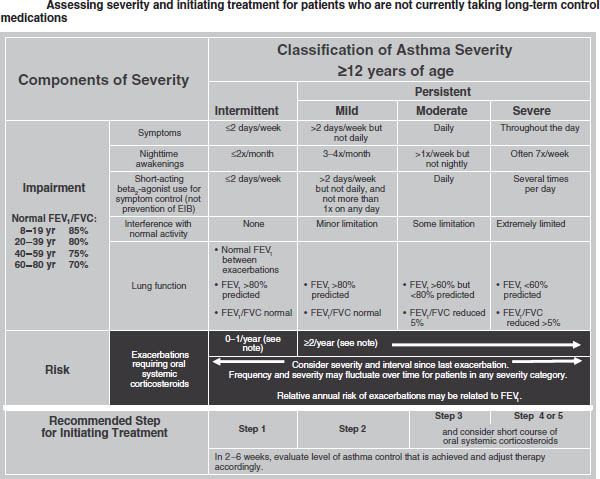

Figure 32-2. Stepwise Approach for Managing Asthma in Infants and Young Children (0–4 Years of Age)

Key: Alphabetical order is used when more than one treatment option is listed within either preferred or alternative therapy. ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, inhaled long-acting beta2-agonist; SABA, inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist

Notes:

■ The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decisionmaking required to meet individual patient needs.

■ If alternative treatment is used and response is inadequate, discontinue it and use the preferred treatment before stepping up.

■ If clear benefit is not observed within 4–6 weeks and patient/family medication technique and adherence are satisfactory, consider adjusting therapy or alternative diagnosis.

■ Studies on children 0–4 years of age are limited. Step 2 preferred therapy is based on Evidence A. All other recommendations are based on expert opinion and extrapolation from studies in older children.

Reproduced from NIH Expert Panel Report 3.

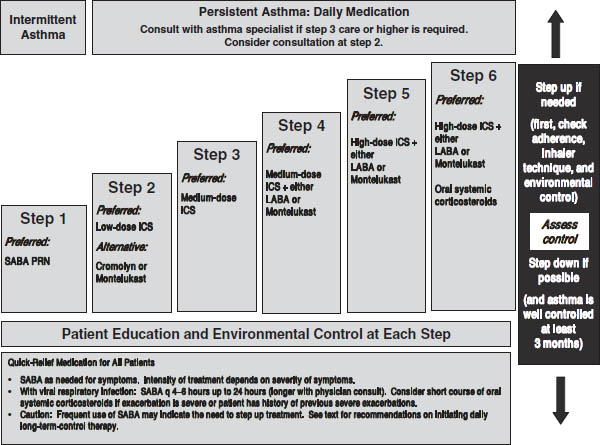

Figure 32-3. Stepwise Approach for Managing Asthma in Children 5–11 Years of Age: Treatment

Key: Alphabetical order is used when more than one treatment option is listed within either preferred or alternative therapy. ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, inhaled long-acting beta2-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; SABA, inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist

Notes:

■ The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decisionmaking required to meet individual patient needs.

■ If alternative treatment is used and response is inadequate, discontinue it and use the preferred treatment before stepping up.

■ Theophylline is a less desirable alternative due to the need to monitor serum concentration levels.

■ Step 1 and step 2 medications are based on Evidence A. Step 3 ICS + adjunctive therapy and ICS are based on Evidence B for efficacy of each treatment and extrapolation from comparator trials in older children and adults—comparator trials are not available for this age group; steps 4–6 are based on expert opinion and extrapolation from studies in older children and adults.

■ Immunotherapy for steps 2–4 is based on Evidence B for house-dust mites, animal danders, and pollens; evidence is weak or lacking for molds and cockroaches. Evidence is strongest for immunotherapy with single allergens. The role of allergy in asthma is greater in children than in adults. Clinicians who administer immunotherapy should be prepared and equipped to identify and treat anaphylaxis that may occur.

Reproduced from NIH Expert Panel Report 3.

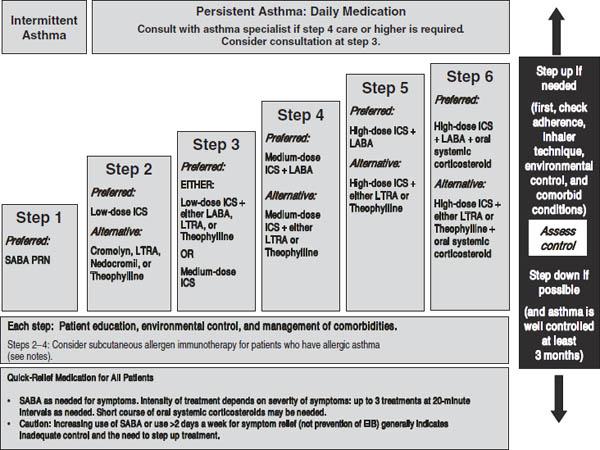

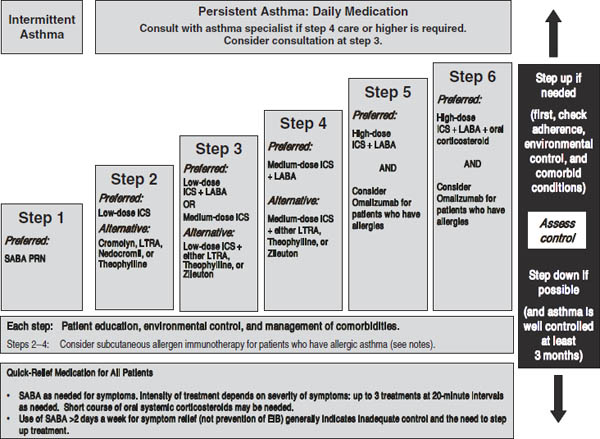

Figure 32-4. Stepwise Approach for Managing Asthma in Children ≥ 12 Years of Age and Adults: Treatment

Key: Alphabetical order is used when more than one treatment option is listed within either preferred or alternative therapy. EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting inhaled beta2-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; SABA, inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist

Notes:

■ The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decisionmaking required to meet individual patient needs.

■ If alternative treatment is used and response is inadequate, discontinue it and use the preferred treatment before stepping up.

■ Zileuton is a less desirable alternative due to limited studies as adjunctive therapy and the need to monitor liver function. Theophylline requires monitoring of serum concentration levels.

■ In step 6, before oral systemic corticosteroids are introduced, a trial of high-dose ICS + LABA + either LTRA, theophylline, or zileuton may be considered, although this approach has not been studied in clinical trials.

■ Step 1, 2, and 3 preferred therapies are based on Evidence A; step 3 alternative therapy is based on Evidence A for LTRA, Evidence B for theophylline, and Evidence D for zileuton. Step 4 preferred therapy is based on Evidence B, and alternative therapy is based on Evidence B for LTRA and theophylline and Evidence D for zileuton. Step 5 preferred therapy is based on Evidence B. Step 6 preferred therapy is based on (EPR—2 1997) and Evidence B for omalizumab.

■ Immunotherapy for steps 2–4 is based on Evidence B for house-dust mites, animal danders, and pollens; evidence is weak or lacking for molds and cockroaches. Evidence is strongest for immunotherapy with single allergens. The role of allergy in asthma is greater in children than in adults.

■ Clinicians who administer immunotherapy or omalizumab should be prepared and equipped to identify and treat anaphylaxis that may occur.

Reproduced from NIH Expert Panel Report 3.

■ There is a complex interaction among inflammatory cells (e.g., mast cells, eosinophils, Th2-type lymphocytes); mediators (e.g., leukotrienes); and cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-5). The result is airway inflammation (mucus and swelling in the lining of the airways) and airway hyperreactivity.

■ Early-phase response to inhaling an aeroallergen occurs immediately; late-phase response occurs 4–12 hours later.

■ Asthma is worsened by poorly controlled concurrent allergic rhinitis and sinusitis. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common in asthma patients, but recent research revealed that although treatment with proton pump inhibitors may improve pulmonary function and asthma-related quality of life, the improvements are minor and of small clinical significance. Asthma may also worsen in the perimenstrual period.

Diagnostic Criteria

■ The main basis for diagnosis is a detailed history of episodic symptoms that are typically worse at night and in the early morning and that are associated with common triggers.

■ Reversible airway obstruction (improvement in pulmonary function tests [FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second] of > 12% after inhaling a short-acting β2-agonist) is often detected.

■ Alternate diagnoses (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and vocal cord dysfunction) should be excluded.

Treatment Principles and Goals

■ Optimal long-term management of asthma includes four major areas: objective assessment and monitoring, environmental control, pharmacologic therapy, and patient education as a partnership.

■ Treatment goals are to achieve asthma control by reducing impairment:

• Prevent chronic and troublesome symptoms (e.g., coughing or breathlessness in the daytime, during the night, or after exercise).

• Require infrequent use (< 2 days/week) of a short-acting inhaled β2-agonist for quick relief of symptoms.

• Maintain (near) “normal” pulmonary function.

• Maintain normal activity levels (including exercise and other physical activity and attendance at work or school).

• Meet patients’ and families’ expectations of and satisfaction with asthma care.

■ Treatment goals are to achieve asthma control by reducing risk:

• Prevent recurrent exacerbations of asthma, and minimize the need for emergency department (ED) visits or hospitalization.

• Prevent progressive loss of lung function; for children, prevent reduced lung growth.

• Provide optimal pharmacotherapy with minimal or no adverse effects.

■ A stepwise approach to managing asthma is shown in Figure 32-2 (ages 0–4), Figure 32-3 (ages 5–11), and Figure 32-4 (ages ≥ 12 and adults). These treatment guidelines are from EPR-3. See Table 32-1 for long-term control medications.

■ Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are the most efficacious drugs for long-term management of persistent asthma. Addition of a long-acting inhaled β2-agonist (LABA) is recommended for patients with moderate or severe persistent asthma. Recent trials have shown that tiotropium (Spiriva) therapy added to patients inadequately controlled with ICS or ICS/LABA combination provides additional benefit.

■ Omalizumab (Xolair): Anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) therapy is primarily indicated for severe persistent asthma patients who have frequent ED visits and hospitalizations despite optimal therapy. It is given subcutaneously every 2–4 weeks.

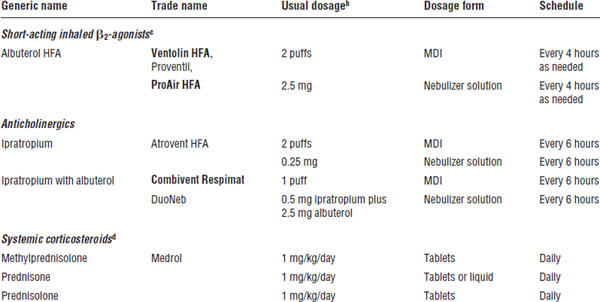

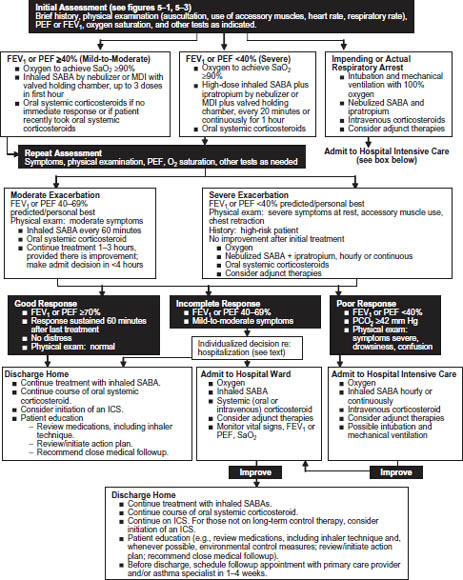

■ Drug therapy for acute exacerbations of asthma is shown in Table 32-2 (quick-relief medications) and Figure 32-5 (management of asthma exacerbations in the ED and hospital).

Monitoring

■ Optimal management for the great majority of patients will result in a dramatic reduction in symptoms (including nocturnal and early morning symptoms), as well as reduced acute care visits, fewer lost work or school days, and reduced need for quick-relief medications.

■ Monitoring peak expiratory flow (PEF) using a peak flow meter at home is helpful in many patients. Green zone is 80–100% of personal best value. Yellow zone is 50–79% of personal best and indicates that consultation with a health care professional is advisable. Red zone, or < 50% of personal best, indicates that a written action plan should be implemented, and, if there is no quick response, immediate medical attention should be sought.

■ Spirometry is usually performed in the physician’s office.

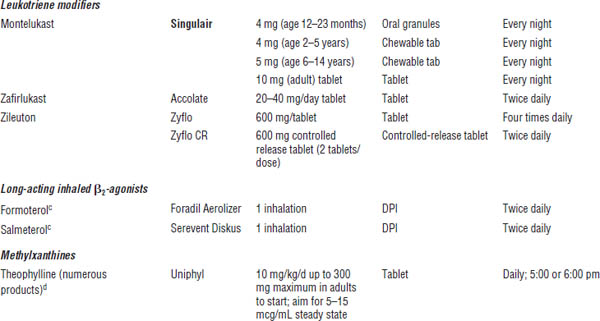

Table 32-1. Long-Term Asthma Control Medicationsa

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

DPI, dry powder inhaler (breath activated); MDI, metered dose inhaler.

a. See EPR-3 and FDA-approved product literature for pediatric doses for each drug product; not a comprehensive list.

b. Usual schedule (some patients do well on once-daily dosing).

c. For asthma patients, use only in combination product with ICS (may use alone in COPD patients, but not asthma patients).

d. Complex, high-risk drug to dose; see references cited for details; do not use unless competent in dosing and monitoring serum theophylline concentrations. See EPR-3 for pediatric doses (< 1 year of age and > 1 year of age).

Table 32-2. Quick-Relief Asthma Medicationsa

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

a. See EPR-3 and FDA-approved product literature for more information, including pediatric doses for each drug product; not a comprehensive list.

b. Usual dosage for routine home use. (Dose in ED is higher and more frequent.)

c. For prevention of exercise-induced asthma, inhale 2 puffs 5–15 minutes before exercise. Increasing use indicates poor asthma control; increase anti-inflammatory therapy and reassess environmental control. (Good asthma control is indicated by infrequent need for quick-relief therapy.)

d. Short courses are used for < 2 weeks.

Mechanism of Action

For more details, see the section on mechanism of action in EPR-3.

Long-term control medications

Corticosteroids

■ Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory. They block late reaction to an allergen and reduce airway hyperresponsiveness. They inhibit cytokine production, adhesion protein activation, and inflammatory cell migration and activation.

■ Corticosteroids reverse β2-receptor down-regulation and inhibit microvascular leakage.

Long-acting β2-agonists

■ With bronchodilation, smooth muscle relaxation follows adenylate cyclase activation and an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP), producing functional antagonism of bronchoconstriction.

■ In vitro, LABAs inhibit mast cell mediator release, decrease vascular permeability, and increase mucociliary clearance.

■ Compared with a short-acting inhaled β2-agonist, salmeterol has a slower onset of action (15–30 minutes). Formoterol has an onset of action within 3 minutes. Both LABAs have a duration of action ≥ 12 hours.

Methylxanthines

■ With bronchodilation, smooth muscle relaxation results from phosphodiesterase inhibition and possibly adenosine antagonism.

■ Methylxanthines may affect eosinophilic infiltration into bronchial mucosa as well as decrease T-lymphocyte numbers in epithelium.

■ Methylxanthines increase diaphragm contractility and mucociliary clearance.

Leukotriene modifiers

■ Leukotriene receptor antagonist; selective competitive inhibitor of CysLT1 receptors

■ 5-Lipoxygenase inhibitor

Figure 32-5. Management of Asthma Exacerbations: Emergency Department and Hospital-Based Care

Key: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; MDI, metered dose inhaler; PCO2, partial pressure carbon dioxide; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SABA, short-acting beta2-agonist; SaO2, oxygen saturation

Reproduced from NIH Expert Panel Report 3.

Anti-IgE therapy

■ Omalizumab (Xolair) is a humanized monoclonal anti-IgE antibody that binds circulating IgE, thus inhibiting the allergic inflammatory cascade that results when aeroallergens bind to IgE on mast cells.

Quick-relief medications

Short-acting inhaled β2-agonists

■ With bronchodilation, smooth muscle relaxation follows adenylate cyclase activation and an increase in cyclic AMP, producing functional antagonism of bronchoconstriction.

Anticholinergics

■ With bronchodilation, there is competitive inhibition of muscarinic cholinergic receptors.

■ Anticholinergics reduce intrinsic vagal tone to the airways. They may block reflex bronchoconstriction secondary to irritants or to reflux esophagus.

■ Anticholinergics may decrease mucus gland secretion.

Patient Instructions and Counseling

■ Patient education is absolutely essential for optimal asthma management.

■ Emphasize the need to take controller–preventer medications every day, even when the patient feels well and is having no breathing problems.

■ Instruct the patient regarding the dangers of overuse of short-acting inhaled β2-agonists. (The patient should contact a physician if the usual dose does not give quick relief or start the written action plan given by the physician.) Patients who purchase the nonprescription racemic epinephrine inhaler (Asthmanefrin EZ Breathe Atomizer) may have persistent asthma and need daily controller medication. Even for intermittent asthma, patients need physician assessment, avoidance of asthma triggers, inhaler instruction, and written action plans. Remember that if quick-relief medication is needed more than twice weekly, the patient has persistent asthma and needs daily controller–preventer treatment.

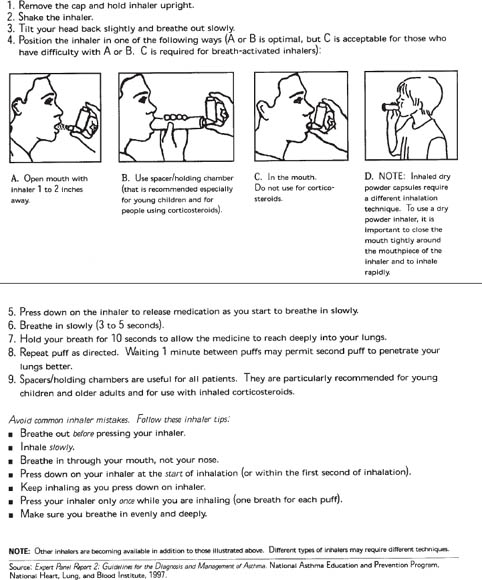

■ Demonstrate the correct use of the metered dose inhaler (MDI), the MDI plus valved holding chamber (or other “spacer”), and the dry powder inhaler (DPI), and then observe the patient using the devices. Most patients do not perform well initially; the devices can be difficult to use at first (see Figure 32-6 for MDI or MDI spacer use). For DPIs, remember to stress that inhalation must be rapid and deep.

■ Demonstrate correct use of peak flow meters, and observe the patient using them (Table 32-3). Explain about the green, yellow, and red zones (including the written action plan).

■ Teach the patient how to prevent exercise-induced asthma.

■ Be sure patients receive an influenza vaccination every fall. For asthma patients age ≥ 19 years, also administer pneumococcal vaccine according to recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations.

Adverse Drug Effects

For more details, see the section on adverse drug effects in EPR-3.

Long-term control medications

Inhaled corticosteroids

■ Inhaled corticosteroids may cause coughing, dysphonia, and oral thrush (candidiasis).

■ In high doses, systemic effects may occur, although studies are not conclusive, and the clinical significance of these effects (e.g., adrenal suppression, osteoporosis, growth suppression, skin thinning, and easy bruising) has not been established.

Long-acting inhaled β2-agonists

■ Tachycardia, skeletal muscle tremor, hypokalemia, or prolongation of QTc interval can occur in an overdose.

■ Use should always be in a combination product with inhaled corticosteroid (Advair, Dulera, or Symbicort) in long-term management of asthma per EPR-3 guidelines. (Use alone could mask inflammation and increase risk of severe exacerbations.)

Methylxanthines

■ Dose-related acute toxicities include tachycardia, nausea and vomiting, tachyarrhythmias (supraventricular), central nervous system stimulation, headache, seizures, hematemesis, hyperglycemia, and hypokalemia.

■ Adverse effects at usual therapeutic doses include insomnia, gastric upset, aggravation of ulcer or reflux, increase in hyperactivity in some children, and difficulty in urination in elderly males with prostatism.

Figure 32-6. Steps for Using an Inhaler

Reproduced from NIH Expert Panel Report 3.

Table 32-3. Directions for Use of Peak Flow Meter

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree