![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the pharmacy student, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. Describe the economic and clinical impact of uncontrolled asthma.

2. List the four components of asthma management.

3. Synthesize a business plan for asthma clinic development in community pharmacies including successful marketing and pricing strategies.

4. Describe the structure of patient visits required in an asthma clinic in a community pharmacy setting.

5. Develop appropriate documentation for prescriber communication, internal documentation, and third-party documentation requirements.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Health Interview Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 13.3% of the population in the United States has been diagnosed with asthma.1 The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America reports the following associated costs of asthma to patients, society, and the health-care system. They state that every day in America:

![]() 40,000 people miss work or school.

40,000 people miss work or school.

![]() 30,000 people have an asthma attack.

30,000 people have an asthma attack.

![]() 5,000 people visit the emergency room (ER).

5,000 people visit the emergency room (ER).

![]() 1,000 people are admitted to the hospital.

1,000 people are admitted to the hospital.

![]() 11 people die.2

11 people die.2

Uncontrolled asthma has negative effects on clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes. The Task Force on Community Preventative Services, a volunteer group of preventative and public health-care experts appointed by the director of the CDC, has recommended an educational and interventional approach to asthma care that has demonstrated an increase in symptom-free days and in cost avoidance. Evidence-based interventions for patients with asthma include proper inhaler technique and trigger identification and avoidance.3

Community pharmacists are uniquely positioned to identify asthma patients with uncontrolled asthma through simple observation such as early or frequent refills of rescue inhalers. A recent study found that community pharmacists were able to identify patients at risk for poorly controlled asthma using assessment tools to determine patient symptoms and medication records to determine appropriate fill history of asthma medications and devices.4

Patient counseling for meter dose inhalers (MDI) and dry powder inhalers (DPI) is an opportunity community pharmacists experience every day that can make a measurable impact on the control of symptoms for patients with asthma. New prescriptions for spacers and peak flow meters also give pharmacists an opportunity to speak with a patient not only regarding the use of a new device but also regarding the reasoning behind the new prescription. An educational intervention may uncover a patient suffering from asthma that is not as well controlled as it could be. Incorrect inhaler technique has been reported frequently in the literature and is estimated to be present in 28–68% of patients.5 Incorrect inhaler technique has been linked to decreased control of asthma symptoms and an increase in ER visits.6 Further research has determined that repeated instruction and demonstration of correct inhaler technique can help to decrease intentional nonadherence to asthma medications.7

One of the most common interventions community pharmacists can utilize is the discovery of underutilization of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) inhalers. Sometimes patients may use multiple pharmacies to fill their asthma prescriptions; however, when rescue inhalers are dispensed, simply questioning a patient about maintenance therapy may be the key to discovering undertreated asthma and suboptimal outcomes for that particular patient.

ASTHMA MANAGEMENT

ASTHMA MANAGEMENT

Definition of Asthma

The National Institutes of Health, National Asthma Education, and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3) defines asthma as the following:

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements play a role: in particular, mast cells, eosinophils, T-lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and epithelial cells. In susceptible individuals, this inflammation causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment. The inflammation also causes an associated increase in the existing bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR) to a variety of stimuli. Reversibility of airflow limitation may be incomplete in some patients with asthma.8

Clinical Presentation of Asthma Symptoms

The majority of asthma symptoms occur due to airway constriction, BHR, and inflammation of the airways.9The symptoms of asthma are highly variable and can even vary within a single person’s lifetime. Exacerbation and remission of symptoms is common. Symptoms can include wheezing (a high-pitched whistling noise resulting from bronchoconstriction), coughing, chest tightness, chest pain, and/or dyspnea.8 During periods of remission, these symptoms may be absent but patients at all stages of asthma have demonstrated airway inflammation, the degree of which can contribute to the severity of the presenting symptoms.10 Persistently inflamed airways can lead to airway remodeling and more permanent decline in lung function.8

Four Components of Asthma Management

The National Institutes of Health, National Asthma Education, and Prevention Program EPR3 recommends four components for effective asthma management.

1. Objective testing, assessment, monitoring, and physical examination to determine asthma control

2. Asthma care education

3. Control of environmental factors and comorbid conditions

4. Pharmacologic therapy8

Pharmacists are well positioned to provide several of these components and to partner with practitioners to ensure patients are not receiving fractionated care for their asthma and to increase the effectiveness of the therapy they are receiving.

Objective Testing

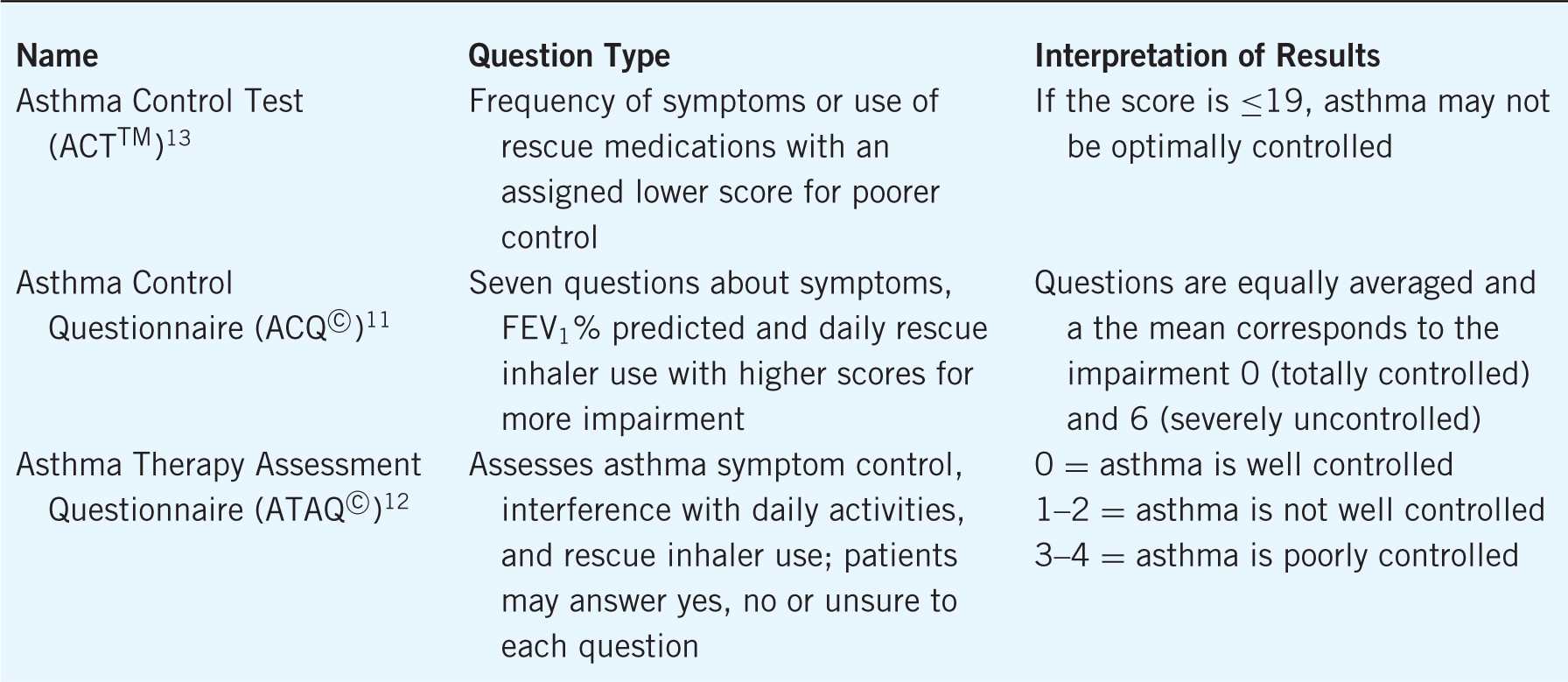

The purpose of assessment and monitoring of asthma is to quantify severity of the disease, control of functional impairment, and responsiveness to treatment. Impairment that symptoms may cause and the risk of asthma exacerbations or decline in lung function help practitioners to determine the patient’s current state of control and set goals for the future.8 Pharmacists and other health-care professionals can assess severity of patient symptoms via validated patient completed questionnaires. Several of these exist and have been used in clinical research to assess and measure changes in control. The Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ©)11, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ©)12, and the Asthma Control Test (ACTTM)13 ask similar questions regarding need and use of rescue inhalers, timing of symptoms, and interruption of activities of daily living caused by asthma symptoms. Each provides a score with interpretation giving the clinician an indication of asthma control and each offers different advantages. For example, the ACQ© includes a section for the clinician to include pulmonary function testing, and the ACTTM includes a version that can be used for children (see Table 5–1 for a comparison of these three questionnaires). Despite the validity of the questionnaires, some patients may be poor perceivers of their lung function, which can be due to many factors such as age, obesity, lack of fitness, or accommodation to symptoms over time.8In these cases, spirometry and lung function testing become even more important.

Table 5–1. Validated Asthma Symptoms Assessment Questionnaires

Spirometry should be used to determine pulmonary function. It is widely available in the clinical setting, and handheld devices are available for purchase in a community pharmacy setting. Spirometry reports pulmonary function by plotting flow of air versus time. Important outcomes for determining asthma control are the forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1). FVC is the total amount of air that can be exhaled. FVC is often expressed as the FEV1. It is important to note that FEV1 can be falsely lowered due to a lack of effort on the part of the patient.14 Values for FEV1 can be predicted based on age and height. Increases in FEV1 ≥12% after inhalation of a bronchodilator from baseline or ≥10% from predicted value objectively indicate treatment effectiveness.8

Spirometry does have a better predictive value of asthma control than peak flow meters, but peak flow meters are affordable, valuable tools for patients to assess their own control. Peak flow meters measure peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) and are recommended for patients with moderate-to-severe asthma. As with spirometry, peak flow monitoring can be highly dependent on patient effort and training is required for their proper use by patients.8

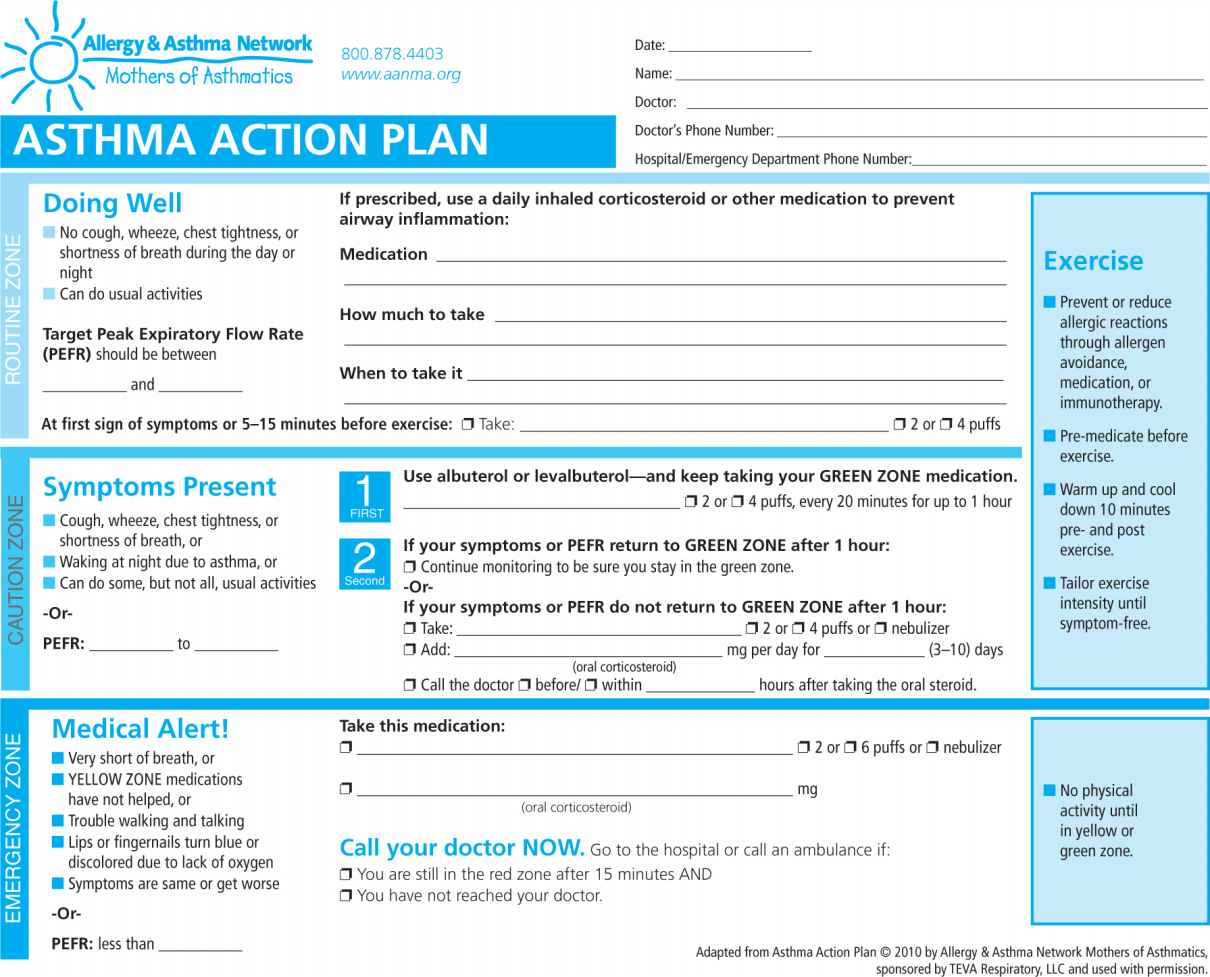

Asthma Care Education

Asthma care education should be collaborative and begin with patients and care givers at the time of diagnosis and continue through follow-up care. The National Institutes of Health, National Asthma Education, and Prevention Program EPR3 recommends components of asthma education that include the level of asthma control the patient can expect, self-monitoring techniques, proper inhaler use, and a written asthma action plan.8 Written asthma action plans explain specific treatment actions taken by the patient in response to changes in symptoms (Fig. 5–4). Pharmacists are particularly helpful in this area of asthma management because it involves helping the patient understand the purpose of his or her medications. In general, asthma medications can be categorized as controllers or rescue medications, and a patient’s ability to distinguish between the two can be of vital importance in exacerbations. Asthma action plans should be updated as needed at follow-up visits and pharmacists should encourage patients to have several copies. For instance, parents should provide a copy to school nurses and teachers for children with asthma or other adults if the child is planning to be away from home for overnight visits.8,15

Asthma education programs are available at many community pharmacies that may include medication therapy management (MTM targeted to patients with asthma. Recognizing the costs of uncontrolled asthma to patients and the health-care system, many states offer reimbursement to community pharmacists for asthma education. The Asheville Project was a monumental achievement for community pharmacists interested in asthma education. The Asheville Project provided education and long-term follow-up to patients with asthma covered by two self-insured third-party payers. Over a 12-month period, pharmacists were able to demonstrate a decrease in emergency department visits, health-care costs related to asthma, and a decrease in missed days of work.16

Control of Environmental Factors and Comorbid Conditions

Pharmacists can use targeted questions and a comprehensive patient history to help determine individualized asthma triggers.8 Pharmacists may find some of the following questions helpful for this assessment:

![]() During which season do you find your asthma symptoms the most severe? Least severe?

During which season do you find your asthma symptoms the most severe? Least severe?

![]() Do you have any pets living inside your home?

Do you have any pets living inside your home?

![]() Have you noticed shortness of breath after eating any foods?

Have you noticed shortness of breath after eating any foods?

Determining the answer to these and other questions can help the patient avoid known triggers. Solutions may be as simple as having the family pet live outside or avoiding fur or feathers in the bedroom. Each of these may help improve asthma symptoms. Additional allergy testing may be required for patients unsure of his or her triggers or unable to identify the cause of escalating symptoms.8

A thorough social history should also include the patient’s occupation. A patient’s occupational exposure to inhaled irritants or tobacco smoke may require the patient to develop a plan with his or her employer to avoid these triggers or, if at all possible, seek employment elsewhere.8

Medication histories should again be continually examined to determine if worsening symptoms could be due to the addition of a new agent, the continuation of an agent such as a nonselective beta-blocker for hypertension or even performance anxiety. Again, this is a vital area in which pharmacists bring their expert medication knowledge to the collaborative health-care team and recommend alternative agents that would avoid worsening asthma symptoms. For each trigger identified, the pharmacist should help the patient devise a plan to decrease exposure to minimize the impact on asthma control.8

Management of comorbid conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD) or obesity should again require the input of the collaborative team managing the patient’s asthma. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as eating smaller meals, elevating the head of the bed, and avoiding food and drink 3 hours before bedtime can help to minimize many GERD symptoms and better help the patient to distinguish between asthma and GERD symptoms. Also, planned careful reduction in caloric intake and increase in exercise, as determined by the health-care team, can help reduce asthma severity in obese patients.8

Medications

Medication management is the area of asthma management in which the pharmacist brings his or her expertise to the collaborative team. An analysis of pharmaceutical care interventions for patients with asthma in community pharmacies, performed by McLean and McKeigan, found improved outcomes, which were demonstrated in programs that provided pharmacists with asthma certification training opportunities, utilized detailed protocols that indicated expectations of the program, and targeted patients with uncontrolled asthma.17

MTM is a separate and distinct service from community pharmacy dispensing activities. During an MTM encounter, a pharmacist spends more focused time with the patient determining the state of current asthma control and specific therapeutic strategies to improve it.

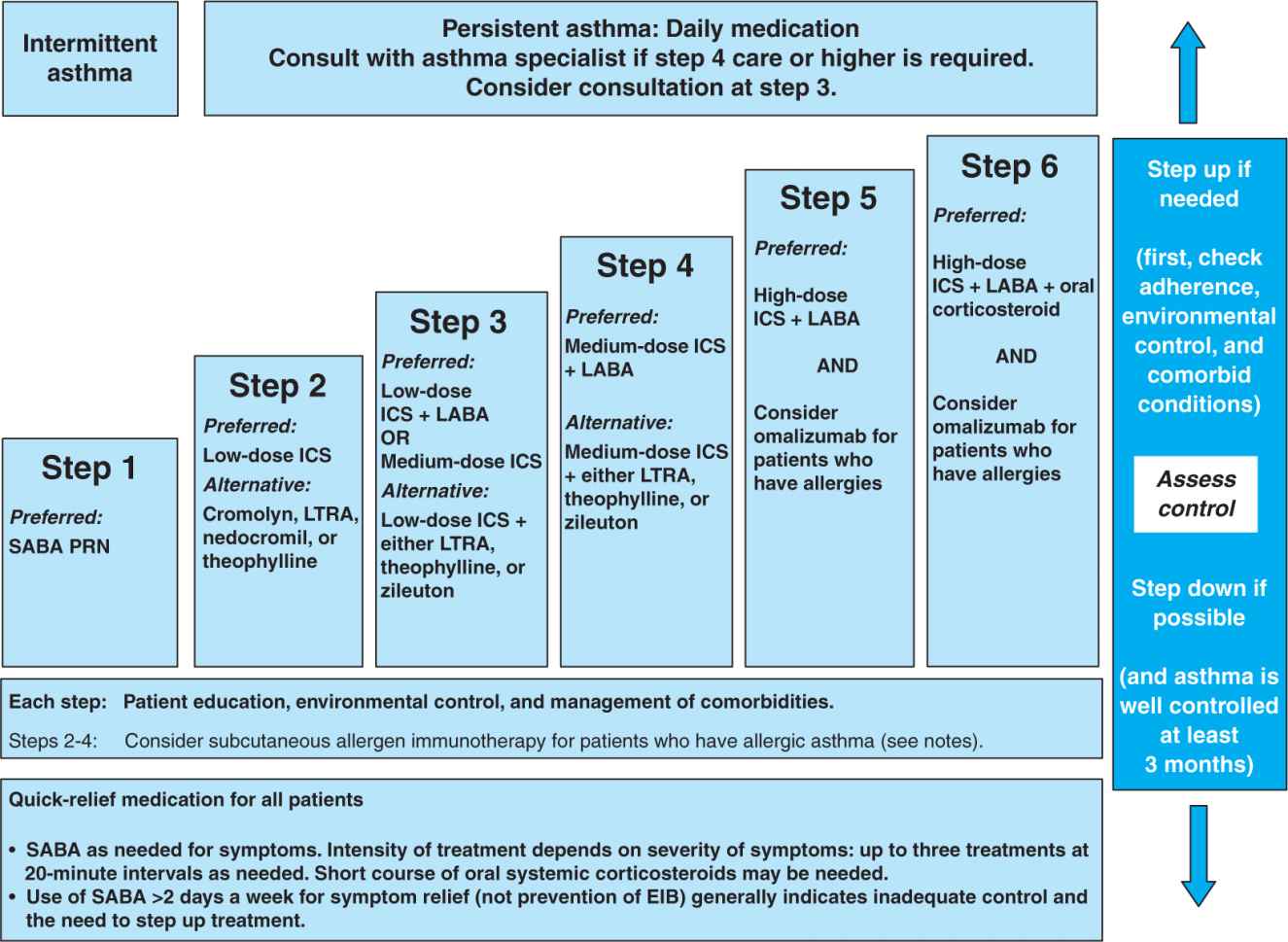

As mentioned earlier, asthma medications are broadly categorized as long-term controller medications and quick-relief medications (Table 5–2). Pharmacists educate patients about which category their medications are classified, the proper use of those medications, potential side effects and strategies to avoid them, and when self-initiation or self-adjustment of doses is appropriate. The written asthma action plan (Fig. 5–1) should be used during these discussions with patients. As will be discussed further, MTM by pharmacists can include patient counseling, device training, adherence monitoring, and recommendations to pre-scribers or even direct management via collaborative practice agreements (CPAs).

Table 5–2. Asthma Medication Classification8

Figure 5–1. Asthma action plan.

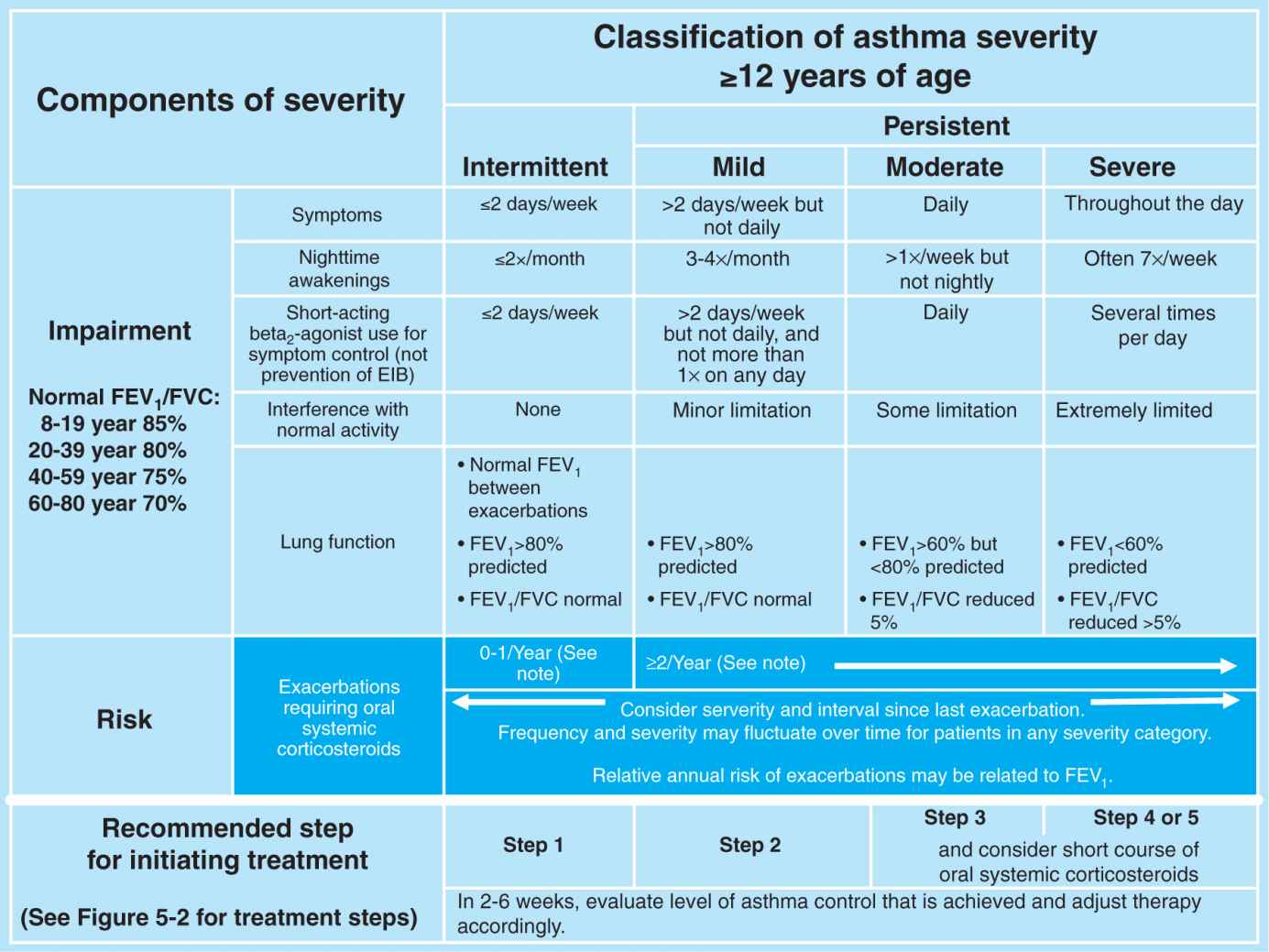

A key aspect of asthma medication management is the classification of the patient’s asthma both by symptoms and pulmonary function testing. As mentioned earlier, validated questionnaires and patient interviews help pharmacists assess symptom control, and spirometry can help confirm these results or help the practitioner become aware of changes in lung function if the patient does not perceive the change. A complete review of the classifications of asthma severity can be found in the National Institutes of Health, National Asthma Education, and Prevention Program EPR 3, but a summary of classifications in patients ≥12 years old can be found in Figure 5–2.8 The guidelines recommend a stepwise approach to therapy depending on severity of the disease (see Fig. 5–38). An individual patient may change classifications over the course of their own disease. It is also recommended that before any changes in therapy be considered, adherence and environmental factors be assessed as possible factors for loss of symptom control or pulmonary function (Fig. 5–2).8 Examples of a stepwise approach to therapy include starting with a short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) for mild asthma. If a patient’s symptoms worsen and the patient needs to use the SABA 2 or more times per week, excluding use prior to exercise, or is awakened by nighttime symptoms, initiating a low or medium-dose ICS would be appropriate. If the patient contracted influenza or pneumonia with severe asthma symptoms, it would be appropriate to increase the ICS to a high dose and add oral corticosteroids.8

— Key: Alphabetical order is used when more than one treatment option is listed within either preferred or alternative therapy. EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting inhaled beta2-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; SABA, inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist

Notes:

![]() The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decision making required to meet individual patient needs.

The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decision making required to meet individual patient needs.

![]() If alternative treatment is used and response is inadequate, discontinue it and use the preferred treatment before stepping up.

If alternative treatment is used and response is inadequate, discontinue it and use the preferred treatment before stepping up.

![]() Zileuton is a less desirable alternative due to limited studies as adjunctive therapy and the need to monitor liver function. Theophylline requires monitoring of serum concentration levels.

Zileuton is a less desirable alternative due to limited studies as adjunctive therapy and the need to monitor liver function. Theophylline requires monitoring of serum concentration levels.

![]() In step 6, before oral systemic corticosteroids are introduced, a trial of high-dose ICS + LABA + either LTRA, theophylline, or zileuton may be considered, although this approach has not been studied in clinical trials.

In step 6, before oral systemic corticosteroids are introduced, a trial of high-dose ICS + LABA + either LTRA, theophylline, or zileuton may be considered, although this approach has not been studied in clinical trials.

![]() Step 1, 2, and 3 preferred therapies are based on Evidence A; step 3 alternative therapy is based on Evidence A for LTRA, Evidence B for theophylline, and Evidence D for zileuton. Step 4 preferred therapy is based on Evidence B, and alternative therapy is based on Evidence B for LTRA and theophylline and Evidence D for zileuton. Step 5 preferred therapy is based on Evidence B. Step 6 preferred therapy is based on (EPR—2 1997) and Evidence B for omalizumab.

Step 1, 2, and 3 preferred therapies are based on Evidence A; step 3 alternative therapy is based on Evidence A for LTRA, Evidence B for theophylline, and Evidence D for zileuton. Step 4 preferred therapy is based on Evidence B, and alternative therapy is based on Evidence B for LTRA and theophylline and Evidence D for zileuton. Step 5 preferred therapy is based on Evidence B. Step 6 preferred therapy is based on (EPR—2 1997) and Evidence B for omalizumab.

![]() Immunotherapy for steps 2–4 is based on Evidence B for house-dust mites, animal danders, and pollens; evidence is weak or lacking for molds and cockroaches. Evidence is strongest for immunotherapy with single allergens. The role of allergy in asthma is greater in children than in adults.

Immunotherapy for steps 2–4 is based on Evidence B for house-dust mites, animal danders, and pollens; evidence is weak or lacking for molds and cockroaches. Evidence is strongest for immunotherapy with single allergens. The role of allergy in asthma is greater in children than in adults.

![]() Clinicians who administer immunotherapy or omalizumab should be prepared and equipped to identify and treat anaphylaxis that may occur.

Clinicians who administer immunotherapy or omalizumab should be prepared and equipped to identify and treat anaphylaxis that may occur.

Figure 5–2. Stepwise approach for managing asthma in youths ≥12 years of age and adults.

__ Assessing severity and initiating treatment for patients who are not currently taking long-term control medications

Key: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICU, intensive care unit

Notes:

![]() The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decision making required to meet individual patient needs.

The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decision making required to meet individual patient needs.

![]() Level of severity is determined by assessment of both impairment and risk. Assess impairment domain by patient’s/caregiver’s recall of previous 2–4 weeks and spirometry. Assign severity to the most severe category in which any feature occurs.

Level of severity is determined by assessment of both impairment and risk. Assess impairment domain by patient’s/caregiver’s recall of previous 2–4 weeks and spirometry. Assign severity to the most severe category in which any feature occurs.

![]() At present, there are inadequate data to correspond frequencies of exacerbations with different levels of asthma severity. In general, more frequent and intense exacerbations (e.g., requiring urgent, unscheduled care, hospitalization, or ICU admission) indicate greater underlying disease severity. For treatment purposes, patients who had ≥2 exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma.

At present, there are inadequate data to correspond frequencies of exacerbations with different levels of asthma severity. In general, more frequent and intense exacerbations (e.g., requiring urgent, unscheduled care, hospitalization, or ICU admission) indicate greater underlying disease severity. For treatment purposes, patients who had ≥2 exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma.

Figure 5–3. Classifying asthma severity and initiating treatment in youths ≥12 years of age and adults.

CLINIC INITIATION

CLINIC INITIATION

Preparing Yourself for Clinic Initiation

As the results of the Asheville Project demonstrate, pharmacist preparedness has an impact on the quality of the pharmacy asthma program. Pharmacists interested in beginning an asthma clinic should hone their clinical skills and become familiar with the latest guidelines available, the medications used, and the assessment techniques.16 The National Asthma Educator Certification Board is an organization that maintains the competencies required of a certified asthma educator (AE-C) through an exam process. Reviews for the Asthma Educator Exam are often provided by local American Lung Association chapters. Pharmacists are eligible to sit for this exam and become credentialed.18 Community pharmacy residencies or pharmacy practice residencies are excellent opportunities to develop not only clinical skills but also marketing and entrepreneurial aspects of implementing an asthma clinic. When pharmacists can demonstrate achievements such as these additional education offerings, it often increases acceptance of new asthma services by both prescribers and patients.

Developing a Business Plan

Environmental Scan

After a pharmacist has established the clinical background necessary to be a competent asthma care provider, a complete scan of the environment should be conducted to ensure that an asthma clinic is feasible, acceptable to stakeholders, and sustainable. If the pharmacist is not the pharmacy manager or owner, he or she must start with garnering support from all decision makers concerning initiating asthma services. This can be accomplished through demonstrating a need. The interested pharmacist should determine the percentage of patient’s refilling rescue inhalers and review the pharmacy’s inventory for use and turnover of asthma-related products. Next, build support from external stakeholders. Physicians or practitioners who are familiar with other services in the pharmacy are the best place to start. For example, if the pharmacy already offers influenza immunizations through a CPA with a provider, he or she would be more likely to support expansion of clinical services than a provider only familiar with dispensing services. Relationships with nurses or clinical support staff are key to the success of any new clinical service. Nurses can identify patients seen at the provider’s office who can be targeted by the new service. If value can be demonstrated to nurses, they can often help overcome any objections or questions raised by prescribers and often ensure referrals to the service that are sent to you with complete information.

Writing the Business Plan

As mentioned earlier in several chapters of this book, a business plan is necessary for the success of any new business venture. Pharmacy services are no exception. Pharmacists should determine if asthma education or MTM services are offered at other institutions in close proximity. For instance, if a local hospital offers free asthma education services and area prescribers are satisfied with the program, it would be difficult to persuade them to refer patients to the pharmacy to pay for the same level of service. If this is the case, pharmacists should survey his or her own business and determine what will set this new service apart. If the service is an expansion from education to disease state management, using any collected data for marketing and justifying the service would help garner buy-in from stakeholders.

Performing a SWOT Analysis A SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis should also be performed. Strengths could include having a residency-trained pharmacist or one who has recently become an AE-C. Other strengths could include a high volume of inhalers dispensed and strong relationships with area providers for other clinic offerings or immunizations. Weaknesses could include a lack of clinical confidence by the pharmacists, a busy workflow making scheduling appointments difficult, or patients who are unaware of the need for the service. Opportunities could include expanding already successful immunization services for patients who have asthma as a natural referral to asthma services within the pharmacy, engaging practitioners with heavy patient load and lack of time for chronic disease education, and capturing available payment for pharmacist-provided services such as with several state Medicaid programs or third-party payers. Threats to the new service could include competitors offering similar services, unwillingness of patients to pay for services if they are not covered through insurance, and the high cost of most asthma medications and devices. A thoughtful business plan will allow the pharmacist to think through each potential threat and develop a plan to avoid or overcome them.

Pricing and Payment for Services When determining pricing strategies, several factors must be considered. First, the cost of administrative materials needed. Whether the pharmacy chooses paper charts or electronic software, this cost, as well as other minimal office supplies, should be considered. If a private patient care area is available, the investment for asthma services would be minimal. However, if a new area is to be constructed, a table, chairs, file cabinet, and asthma handouts should be obtained. Partnering with an area pharmaceutical sales representative can be invaluable in the beginning because he or she can often provide handouts, models, coupons, and demonstration inhalers. Second, at a minimum, a peak flow meter with disposable mouthpieces will be needed for patients to demonstrate its use and to assess peak flow rates at visits. Handheld spirometry is optional equipment that would help to solidify recommendations and assessment of lung function, but it can be expensive. Pharmacies or clinics may consider initially investing in this equipment or could consider investing in it after the service begins generating revenue.

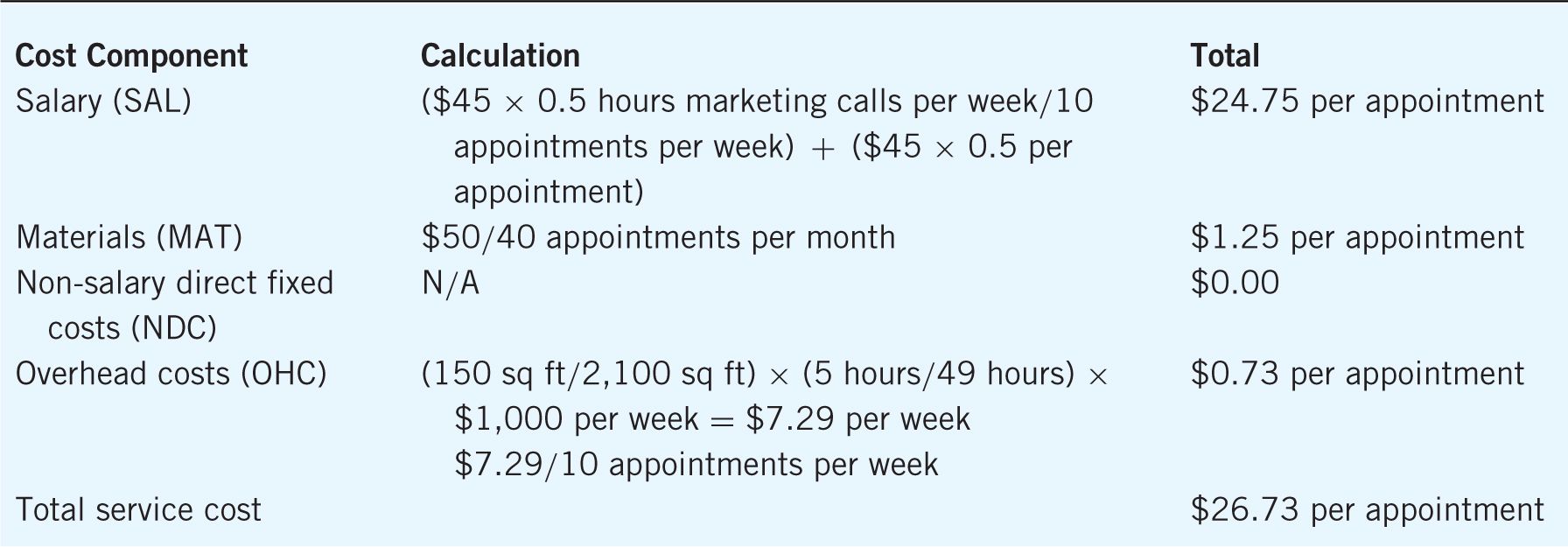

Before methods of payment for services are determined, correct pricing of services must be considered. Pricing can be determined by including the salary of all personnel involved (SAL), materials and supplies (MAT), non-salary direct fixed costs (NDC) such as glucometer strips if diabetes services were offered, and rent or non-rent overhead costs (OHC).

Cost = SAL + MAT + NDC + OHC19

For example, Our Family Pharmacy is interested in starting asthma disease state management services. It is an independent pharmacy open Monday through Friday from 9 AM to 6 PM. The weekly rent for the 2,100 square foot store is $1,000 and pharmacists are paid $45 per hour. How much should it charge for 30-minute asthma MTM appointment?

Our Family Pharmacy has a 150 square foot patient care office and is estimating 10 appointments per week after beginning the asthma service. The pharmacist will be the only personnel seeing patients and scheduling appointments. Our Family Pharmacy has decided to utilize paper charts and estimate nominal office supplies to be about $50.00. A pharmaceutical sales representative donated a peak flow meter, mouthpieces, and demonstration inhalers. Marketing plans include practitioner calls totaling about 30 minutes (Table 5–3).19

Table 5–3. Total Service Cost

Knowing that a 30-minute MTM appointment will cost the pharmacy $26.43, how much should the pharmacy charge for the asthma pharmacy services appointments?

Several components must be considered in order to determine the best price. Demand for services is a critical consideration. If a pharmacy has already built a strong patient base with considerable trust in the pharmacists and has patients who need better management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree