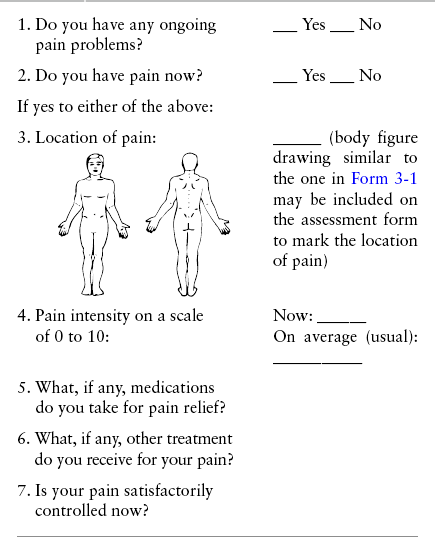

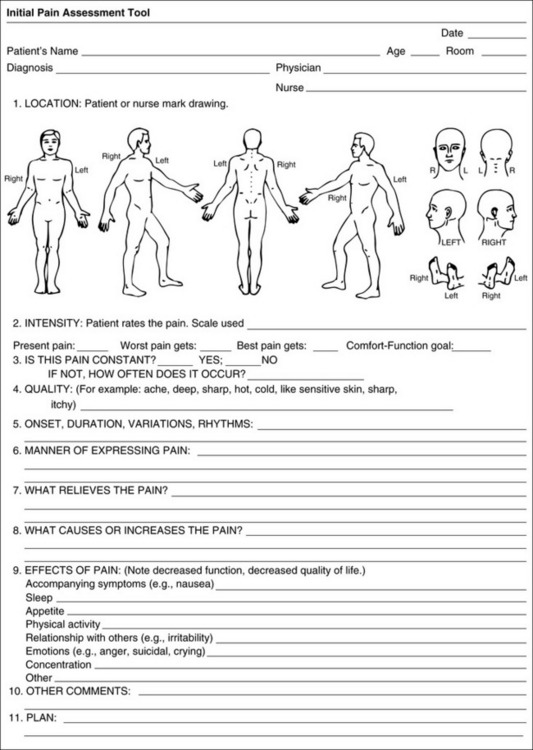

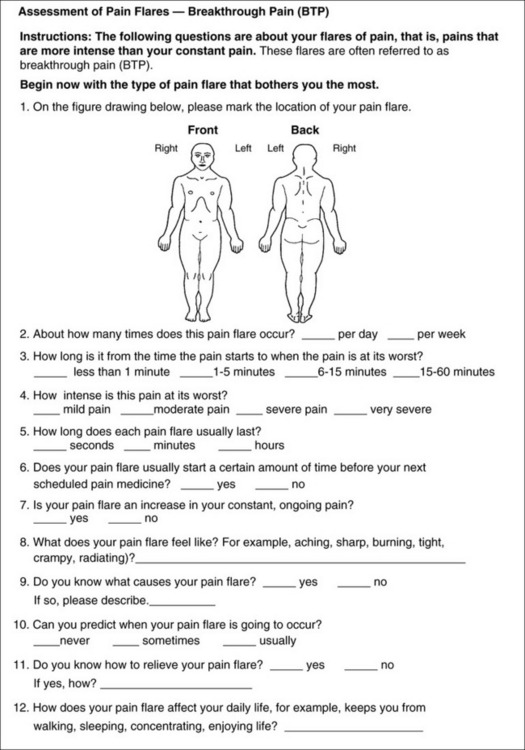

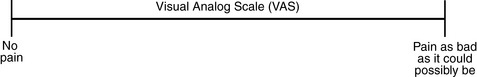

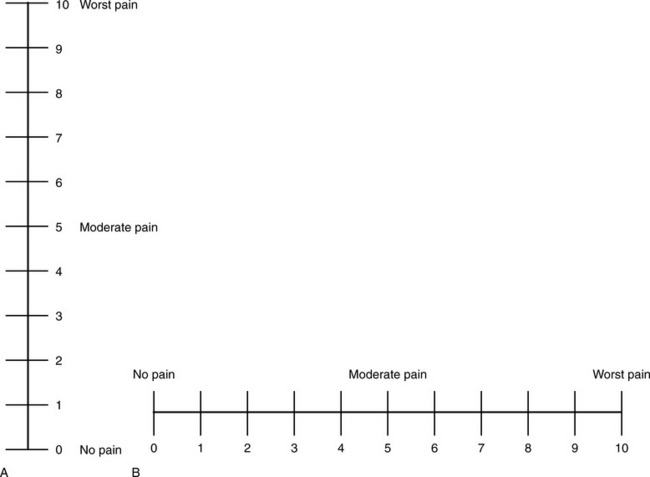

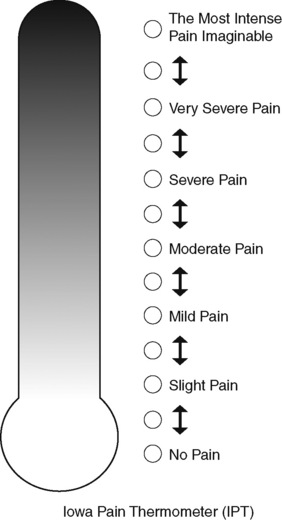

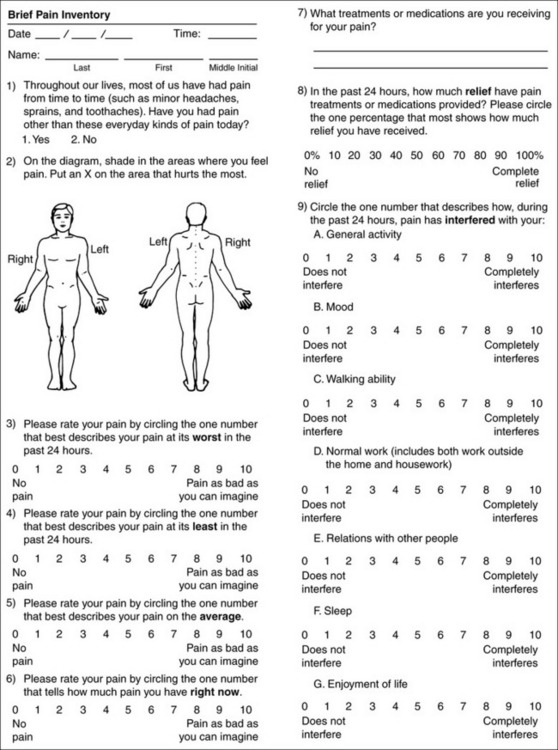

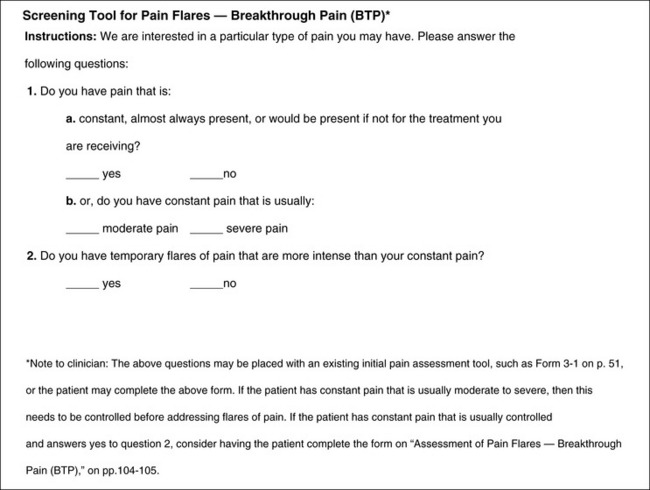

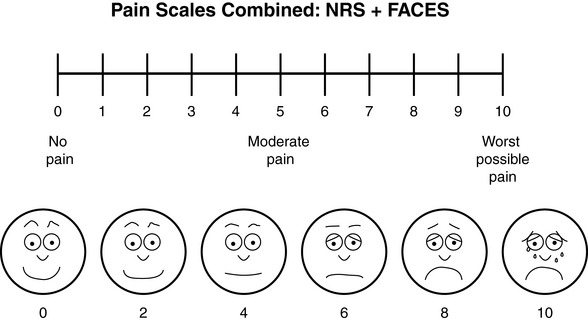

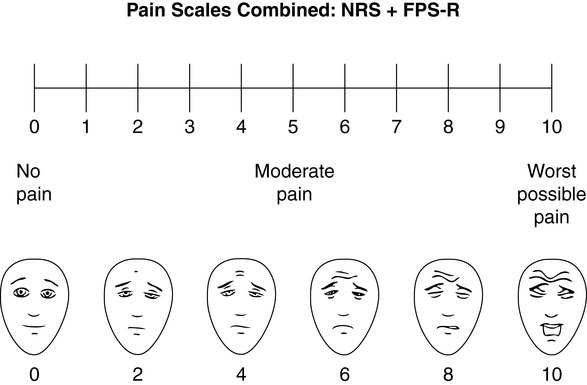

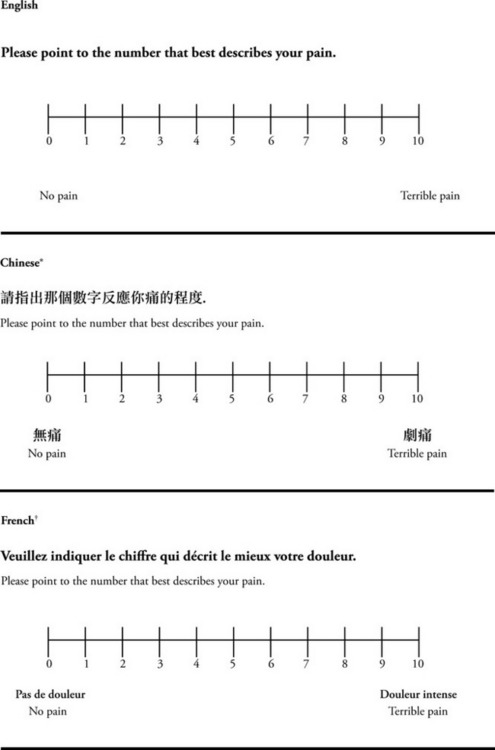

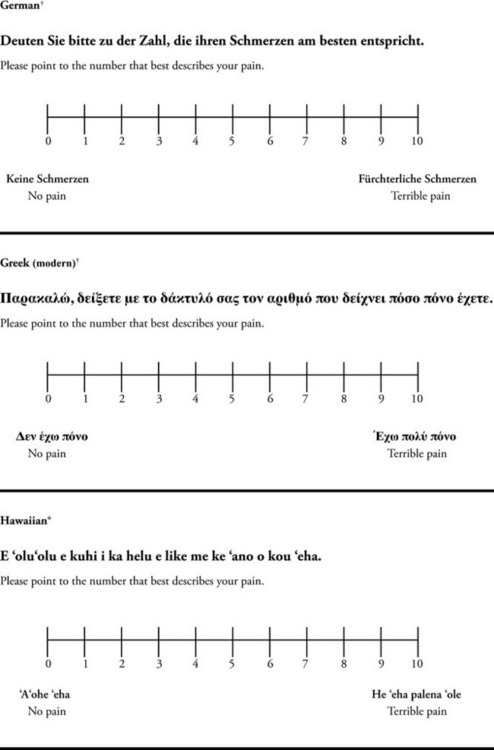

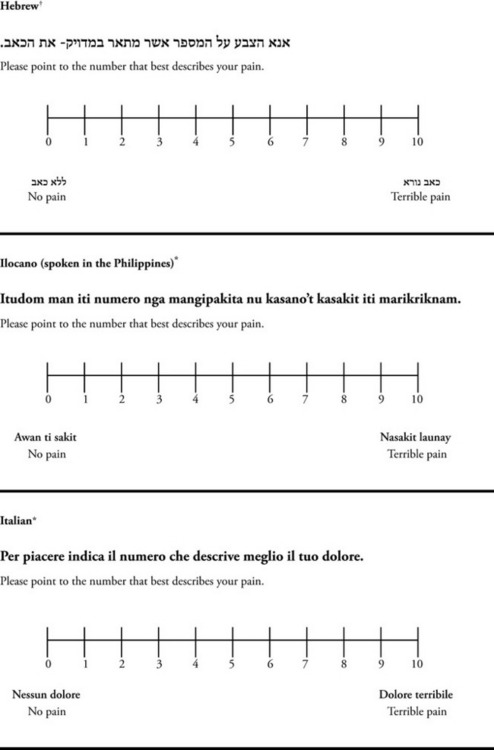

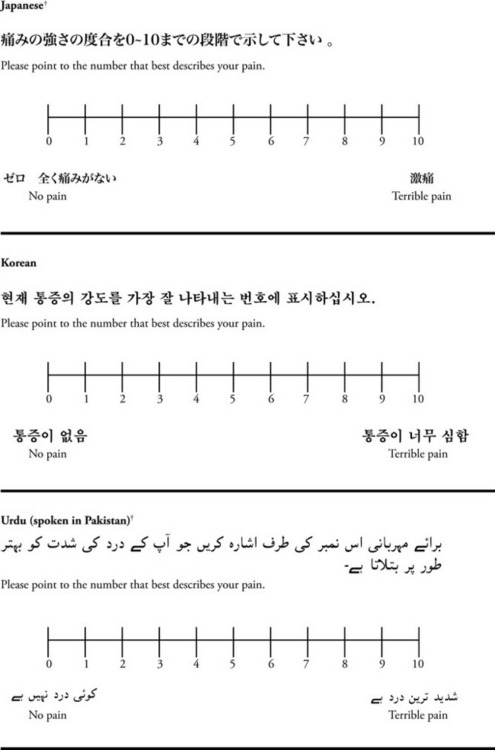

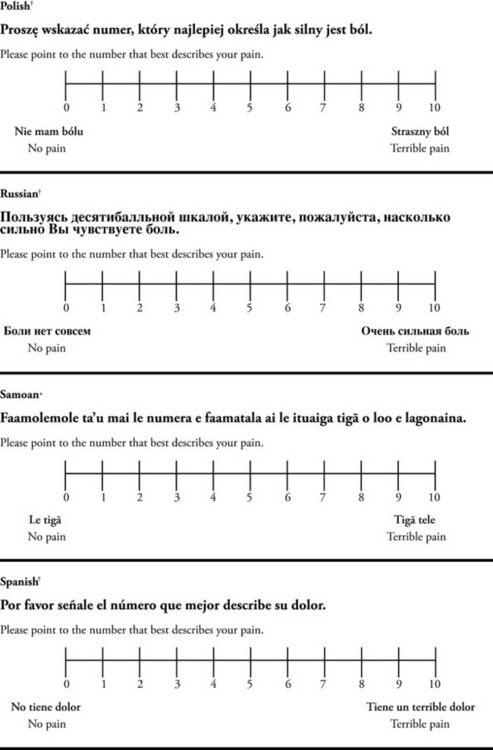

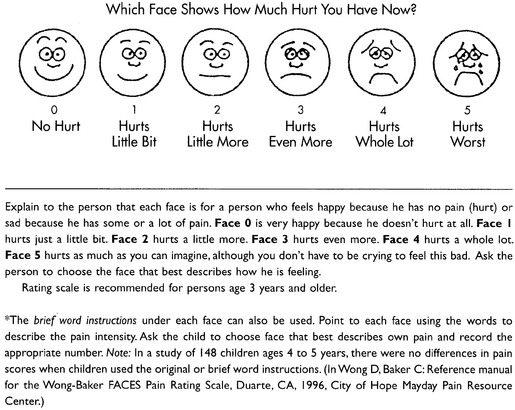

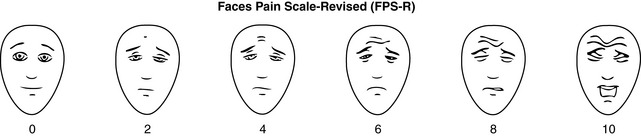

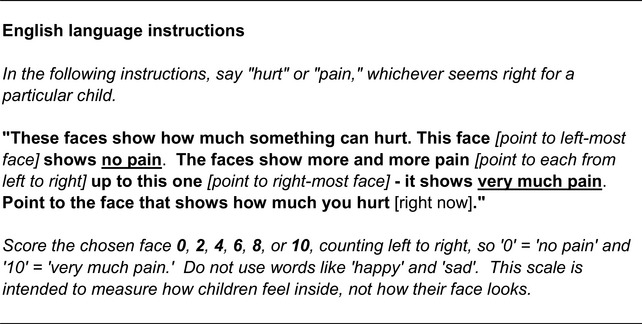

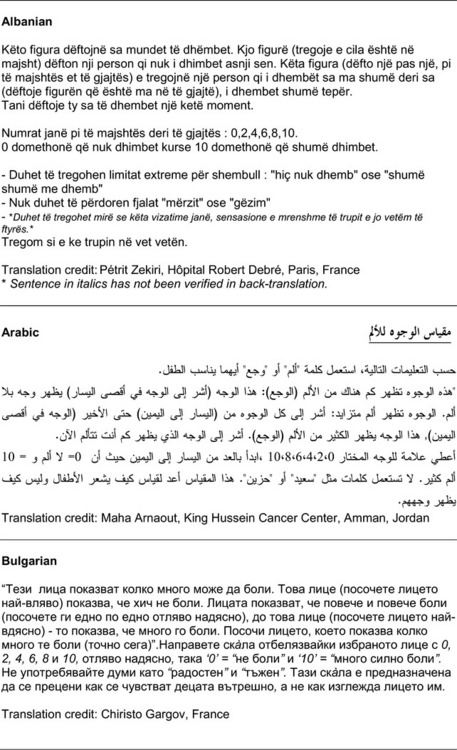

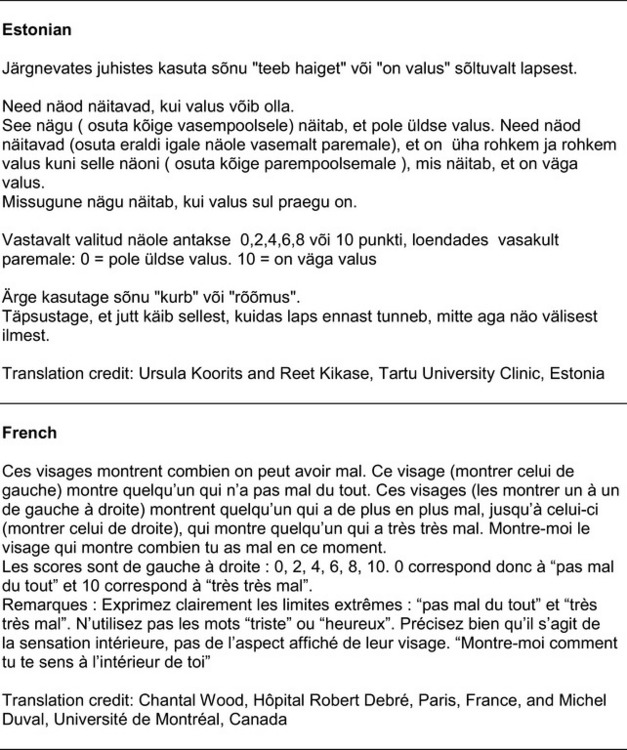

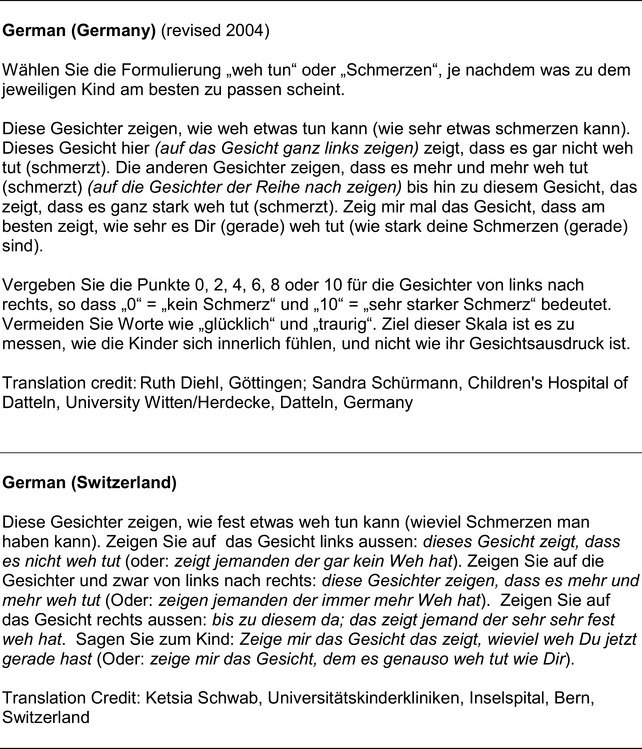

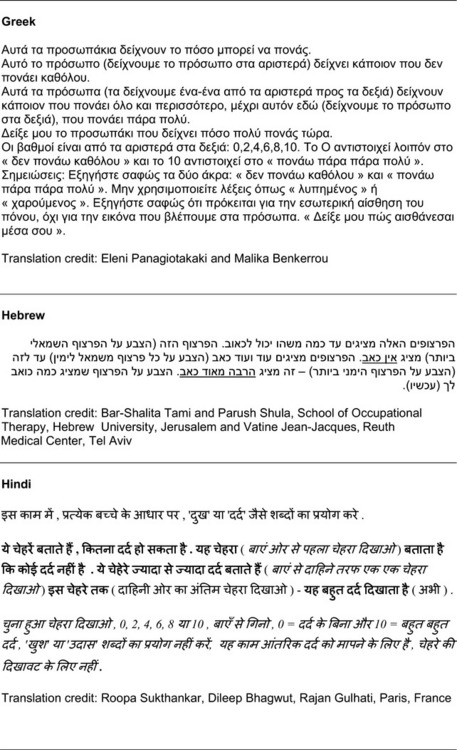

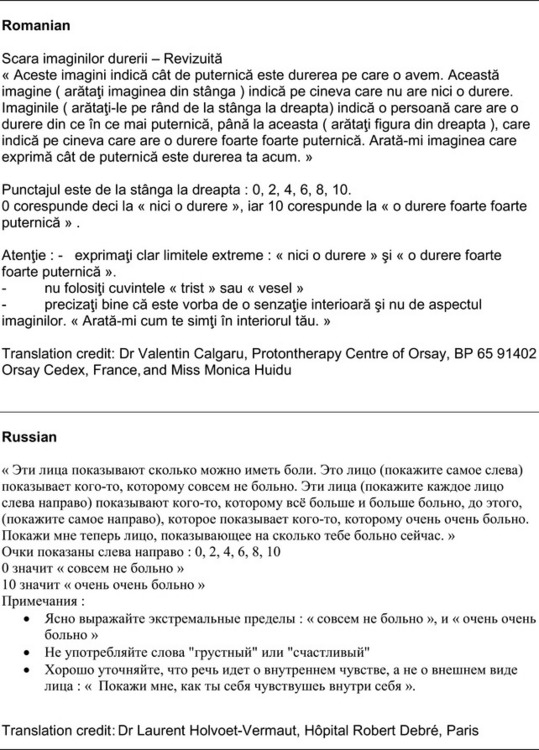

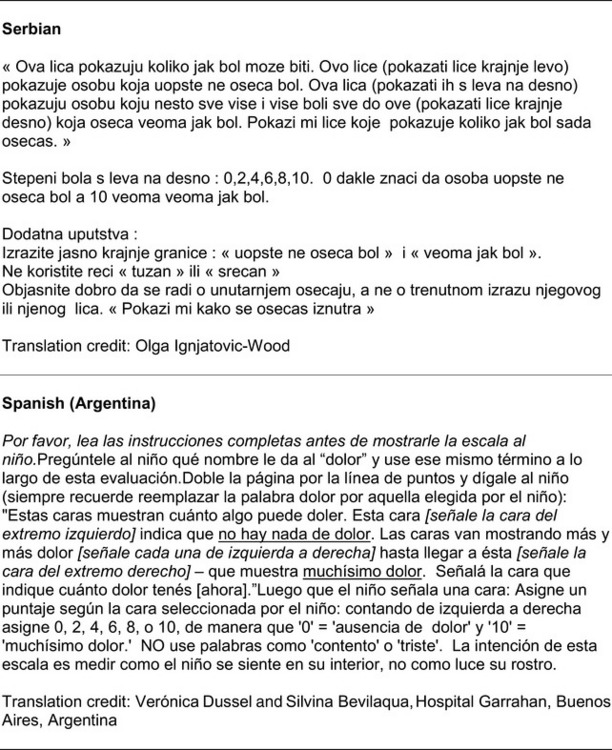

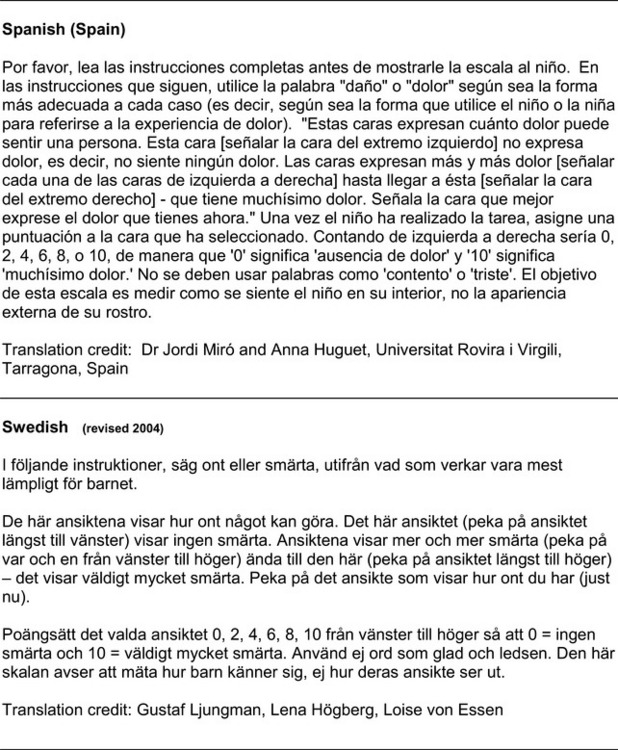

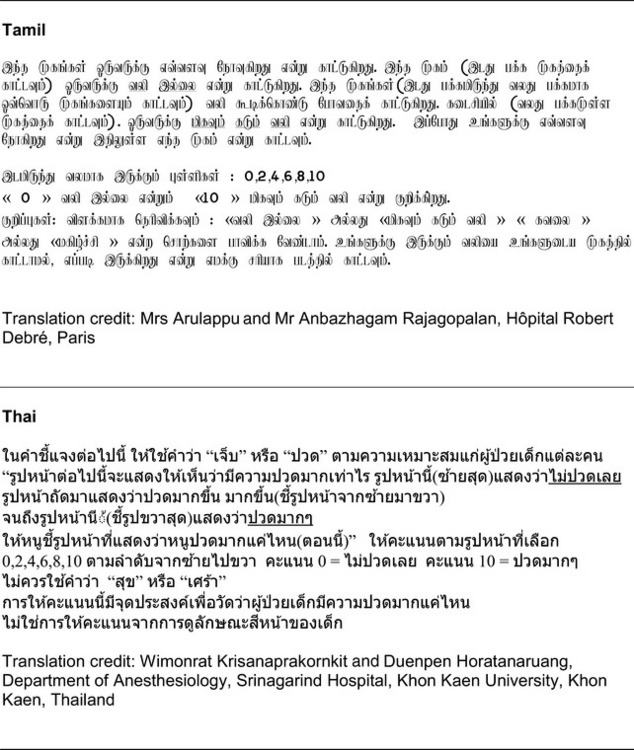

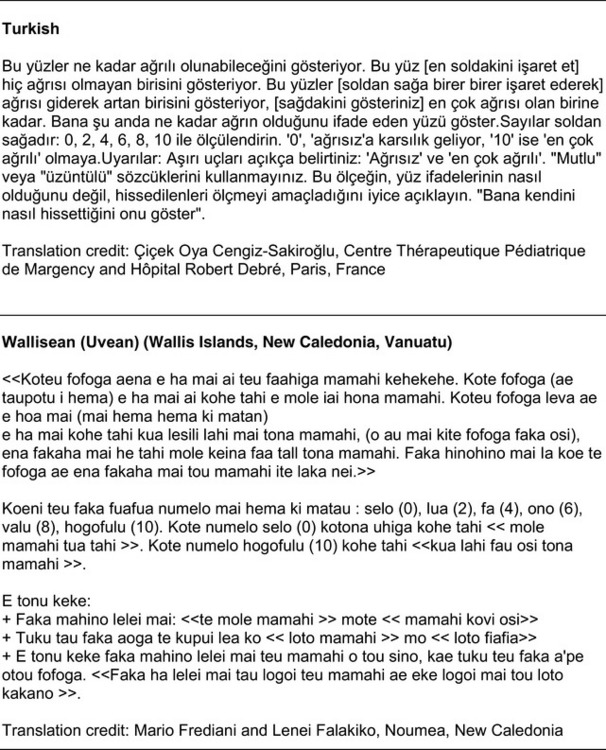

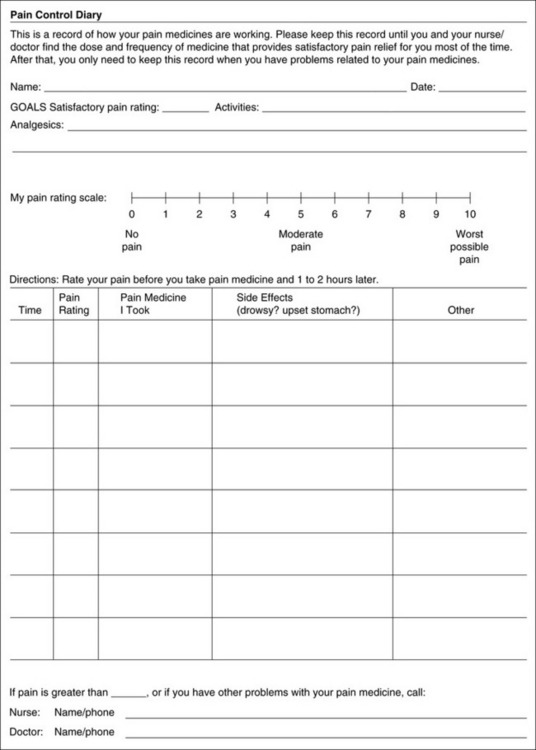

Chapter 3 Tools for Initial Pain Assessment Criteria for Selecting of Pain Rating Scales for Use in Daily Clinical Practice Principles of Using Pain Rating Scales Teaching Patients and Families How to Use a Pain Rating Scale Patients Who Deny Pain or Refuse Pain Relief Selection of Pain Rating Scales for Patients Who Have Difficulty with the Commonly Used Self-Report Scales Assessment of Neuropathic Pain Assessment of Breakthrough Pain Flow Sheets for Analgesic Infusions in Acute Care Pain Diaries for Outpatient Care Clinic Record for Reassessment of Patients with Persistent Pain Who Are Taking Opioids Pain Assessment in Patients Who Cannot Self-Report Types of Behavioral Pain Assessment Tools Tools for Assessing Pain in Cognitively Impaired Patients and Others Who Cannot Self-Report Recommended Tools for Patients Who Cannot Self-Report When patients are admitted to a health care facility, such as a hospital or an outpatient clinic, nurses perform general admission assessments. Along with such information as the patient’s self-care abilities and nutritional needs, a section should be included to identify pain problems. Patients may have chronic pain conditions for which they are already receiving treatment, or pain may be the primary reason for admission. Examples of questions that are appropriate for routine admission assessments are shown in Box 3-1. The purpose of these questions is to identify new or ongoing pain problems. If a pain problem is ongoing and the patient already has an effective pain treatment plan, steps should be taken to ensure that the plan is continued. If a treatment plan must be developed, further assessments using the Initial Pain Assessment Tool (Form 3-1, p. 51) or the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI; Form 3-2, p. 53) may be indicated. Form 3-2 From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 53, St. Louis, Mosby. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Two tools widely used for overall initial pain assessments are referred to as Initial Pain Assessment Tool (see Form 3-1) and the BPI (see Form 3-2). Both of these were included in the cancer pain clinical guidelines published by the Agency for Health Policy and Research (Jacox, Carr, Payne, et al., 1994a), and the BPI is included in the revised cancer pain guidelines published by APS (Miaskowski, Cleary, Burney, et al., 2005). The patient or the clinician may complete these tools. Another overall pain assessment tool often used in research and clinical practice is the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack, 1987). The Initial Pain Assessment Tool (Form 3-1) may be completed by the patient or used to guide the clinician in collecting information about the patient’s pain. A discussion of each assessment point follows. 1. Location of pain. This is most easily and quickly accomplished by asking the patient to mark the location on the figure drawings. Alternately, the clinician may ask the patient to point to the locations of pain on his or her own bodies, and the clinician can mark figure drawings. If there is more than one site of pain, letters (A, B, C, etc.) may be used to distinguish the various sites. These letters may be used in answering the remainder of the questions. 2. Intensity. The pain rating scale used by the patient is identified. The patient is asked to rate pain intensity for present pain, worst pain, the least pain felt, and comfort-function goals (pain rating that will not interfere with necessary or desired functioning, such as ambulation and decreased anxiety). If the patient has more than one site of pain, the letter designations mentioned simplify recording. For example, for present pain intensity, the recording might be A = 4, B = 6. A time period may be specified for answering the next questions about pain intensity. For example, worst pain intensity may be asked in relation to the past 24 hours or the past week. 3. Is this pain constant? If not, how often does it occur? These questions help screen for the presence of breakthrough pain (BTP), defined as a transitory increase in pain that occurs on a background of otherwise controlled chronic pain. If the patient says the pain is constant, this rules out BTP. But if the patient say the pain is not constant, further questioning is indicated, specifically asking the patient whether there are temporary flares of pain that are more intense than the constant pain. The Screening Tool for Pain Flares—Breakthrough Pain, Form 3-6 (p. 103), and the Assessment of Pain Flares—Breakthrough Pain, Form 3-7 (p. 104), may be helpful. Roughly 50% or more of patients with chronic, constant pain also have BTP that might be overlooked. Form 3-6 From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 103, St. Louis, Mosby. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. 4. Quality of pain. This information is helpful in diagnosing the underlying pain mechanism. Soreness is commonly more likely to be indicative of somatic pain, whereas burning or knifelike pain is more likely to be indicative of neuropathic pain. This information may have direct implications for the type of pain treatment chosen. For example, an anticonvulsant (an adjuvant analgesic; see Section V) may be indicated for knifelike pain. One study found that the quality of pain seemed to cluster in three groups: (1) paroxysmal pain sensations, such as shooting, sharp, and radiating pains; (2) superficial pain, such as itchy, cold, sensitive, and tingling pains; and (3) deep pain, such as aching, dull, cramping, and throbbing pain (Victor, Jensen, Gammaitoni, et al., 2008). 5. Onset, duration, variations, rhythms. To detect variations and rhythms, ask the patient, “When did this pain begin?” “Is the pain better or worse at certain times, certain hours of the day or night, or certain times of the month?” 6. Manner of expressing pain. Ask the patient if he or she is hesitant or embarrassed to discuss the pain or whether the patient tries to hide it from others. Ask the patient if using the pain rating scale is acceptable. 7. What relieves the pain? If the patient has had pain for a while, he or she may know which medications and doses are helpful and may have found some nondrug methods, such as cold packs, helpful. If appropriate, these methods should be continued. 8. What causes or increases the pain? A variety of activities, body positions, and other events may increase pain, and efforts can be made to avoid them or to provide additional analgesia at those times. 9. Effects of pain. These items help to identify how pain affects the patient’s quality of life and how pain interferes with recovery from illness. Information obtained in this section may be useful in developing pain management goals. If pain interferes with sleep, a major goal may be to identify a pain rating that will allow the patient to sleep through the night without being awakened by pain. 10. Other comments. No tool is comprehensive. This space simply allows for information the patient may wish to add. 11. Plan. Immediate and long-range plans can be mentioned here and developed in greater detail as time passes. The BPI (Form 3-2, p. 53) is a 9-item tool that gathers information about pain severity and rates level of pain interference with seven key areas of function. Regular use of this tool helps track progress in treating pain intensity and degree of pain interference with general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work (both work outside the home and house work), relations with other people, sleep, and enjoyment of life. The BPI is relatively short and easy for patients to complete, taking about 10 to 15 minutes. It has been used successfully with older adults (Ersek, Turner, Cain, et al., 2004; Kemp, Ersek, Turner, 2005). Questions on the BPI focus on pain during the past 24 hours. • Question 1 asks if the patient has experienced pain other than common everyday kinds of pain and if the patient has experienced that pain today. • Question 2 asks the patient to identify the location of that pain in the figure drawing. • Questions 3 through 6 ask the patient to use a pain rating scale of 0 to 10 to rate pain at its worst and least in the past 24 hours and its intensity on average and right now. • Question 7 asks about treatment or medication the patient is receiving for pain. • Question 8 asks the percentage of pain relief provided by these treatments. • Question 9 has seven parts that attempt to identify how much pain has interfered with the patient’s life, including general activity, mood, work, sleep, and enjoyment of life. Criteria for selecting self-report pain rating scales for use in daily clinical practice are summarized in Box 3-2. Most important, the pain rating scale selected must have been tested and found to be reliable and valid. Reliability means that the scale consistently measures pain intensity from one time to the next, and validity means that the scale accurately measures pain intensity. Probably the most fundamental aspect of validity for pain rating scales is that they demonstrate sensitivity to changes in the magnitude of pain (Herr, Spratt, Garand, et al., 2007). For example, they must be sensitive enough to measure effects of analgesic medication. (For more detailed information about the reliability and validity of a variety of pain measures, refer to Jensen [2003] and Herr, Spratt, Mobily, et al. [2004]). Usually the main purpose of using pain rating scales in clinical practice is to identify the intensity of pain over time for the purpose of evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to relieve pain. Scales used to obtain self-reports of pain intensity fail to provide other information that is important to assessing pain and determining pain treatment. This is one of the reasons for remembering to use the Initial Pain Assessment Tool (see Form 3-1) or the Brief Pain Inventory (see Form 3-2). As stated in Box 3-2, the tool also should be sufficiently graded so it can capture changes in pain intensity and should be easily understood, easy to score, and liked by patients and staff. The tool should place a low burden on staff; that is, it should be quickly explainable and easily scored. It should also be inexpensive and easy to duplicate. The tool should also be appropriate for patients of various cultures and available in several languages. Currently, the term VAS is used loosely and inaccurately to refer to several different pain intensity scales such as the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). However, the VAS has a fairly precise definition as a horizontal (sometimes vertical) 10-cm line (100 mm) with word anchors at the extremes, such as “no pain” on one end and “pain as bad as it could be” on the other end (Figure 3-1). The patient is asked to make a mark on the line to represent pain intensity. In this manual, the term VAS refers only to a horizontal or vertical straight line with word anchors at the ends. Probably because the VAS is reliable and valid and is commonly used in research, it is sometimes used in clinical practice. However, it has several disadvantages in that setting. Although the VAS is usually easy to administer (unless the patient has an injury to the arm or hand or is lying down) and easy to reproduce, scoring is time consuming. As mentioned, the patient is asked to mark the line to indicate the level of pain. A number is then obtained by measuring in millimeters up to the point the patient has indicated. Also, without specific numbers being arranged along the VAS line, it is difficult to use the scale to discuss pain rating goals with the patient, especially over the telephone. Further, patients tend to have more difficulty understanding and using a VAS than the other scales such as the NRS (Herr, Spratt, Mobily, et al., 2004; Jensen, Karoly, 1992; Peters, Patijn, Lame, 2007). In research comparing the VAS with the verbal descriptor scale (VDS) and with 11-point and 21-point numeric box scales, patients made more mistakes using the VAS (Peters, Patijn, Lame, 2007). (A box scale shows connected boxes along a vertical or horizontal line with numbers in the boxes, such as 0 to 10 or 0 to 20. Figure 3-2 is an example.) After we (the authors) considered a wide array of pain intensity rating scales, the self-report scales we now recommend for use in clinical practice with cognitively intact adolescents, adults, and older adults consist of the NRS plus a faces pain rating scale (Box 3-3). This gives the patient a choice of using either the NRS or a faces scale. Some patients are unable to understand the NRS but are able to use one of the faces scales. Other patients simply do not like the NRS. For example, in a study of 267 hospitalized patients ranging in age from 16 to 91 years, almost half preferred the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (FACES) to the 0 to 10 NRS or the VAS (Carey, Turpin, Smith, et al., 1997). Specifically, we suggest a horizontal NRS using 0 to 10 (0 = no pain; 10 = worst possible pain) presented visually. The patient is asked to report a number or mark the scale. Or the patient may choose a faces scale. We recommend that the NRS be combined with either (a) the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (FACES), using 0 to 10 to represent the 6 faces; or (b) the Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R), again using 0 to 10 to represent the 6 faces (Figures 3-3 and 3-4). No single-word anchor has been identified as being the best one for the number 10 on the 0 to 10 scale. Examples of word anchors that have been used fairly frequently are “worst imaginabale pain,” “worst possible pain,” “most intense pain imaginable,” “terrible pain,” and “pain as bad as it can be.” Figure 3-3 Example of how the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) can be combined with the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating (FACES) in a horizontal format with a 0-to-10 metric and placed on the same paper or card to present to patients. They have a choice of pain rating scales. If the NRS is not easily understood, the FACES scale is an alternative. From Hockenberry, M. J., Wilson, D., & Winkelstein, M. L. (2005). Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 7, St Louis, Mosby, p. 1259. Used with permission. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 56, St. Louis, Mosby. Permission to use the FACES scale for purposes other than clinical practice can be obtained at http://www.us.elsevierhealth.com/FACES/. The NRS is in the public domain. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Figure 3-4 Example of how the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) can be combined with the FPS-R in a horizontal format with a 0-to-10 metric and placed on the same paper or card to present to patients. Patients have a choice of pain rating scales. If the NRS is not easily understood, the FPS-R scale is an alternative. As appears in Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 57, St. Louis, Mosby. This figure has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the Study of Pain. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Permission to use the FPS-R for purposes other than clinical practice or research can be obtained by e-mailing IASPdesk@iasp-pain.org. The NRS is in the public domain. Numerical Rating Scale: The NRS is sometimes presented as a 0 to 5 scale or as a vertical line, but in this manual, unless otherwise specified, NRS refers to a 0 to 10 horizontal scale with numbers between 0 and 10. Although occasionally the 0 to 5 scale is appropriate for patients who are unable to comprehend more items on a scale, the 0 to 10 is now widely accepted. In a survey of health care professionals that asked them which scale they preferred for use in clinical practice, the majority (70%) favored 0 to 10 (von Baeyer, Hicks, 2000). Regarding use of the horizontal line, it is worth noting that research indicates that the vertical VAS may be more sensitive and easier for patients to use, especially patients who are under the stress of having a narrowed visual field (Gift, 1989; Gift, Plaut, Jacox, 1986). Further, some research has found that the vertical format may be more easily understood by older persons (Herr, Garand, 2001; Herr, Mobily, 1993). Therefore, the vertical NRS (Figure 3-5, A) may be advisable for some patient populations or may be presented as an alternative to patients who have difficulty with the horizontal scale (Figure 3-5, B). When patients, such as very cognitively impaired patients and unconscious patients, are unable to self-report pain one must begin to rely on known pathology and behavioral indicators (see Box 3-9, p. 123). Otherwise, the gold standard for measuring pain intensity is a self-report, such as a number or word. Another problem we (the authors) have seen across the United States is clinicians’ attaching behaviors to each number on the NRS and asking patients to state a number to indicate their pain levels. These scales are seldom published but are nevertheless used in clinical practice in some institutions. In one example of a 0 to 10 NRS with behaviors attached to each number, the number 5 was accompanied by the statement that pain “can’t be ignored for more than 30 minutes.” This has not been researched and is negated by the statements of many patients who have practiced learning to ignore pain. This also requires timing how long patients can ignore pain, which is cumbersome, time consuming, and a little on the humorous side. The same scale stated with the number 7 that pain “interferes with sleep,” again contradicted by patients who have learned to use sleep as a coping mechanism. (Readers may want to review the section on the acute pain model, presented earlier in this manual, on pp. 28-29). Again, on the humorous side, that same scale stated with the number 10 that “pain makes you pass out.” Again, no research substantiates this, and it makes it almost impossible for patients to rate pain as a 10 because they would be unconscious. Patients’ behavioral responses vary enormously and cannot be pigeonholed at one particular level of pain. Patients cannot be told how they have to behave in order to rate their pain at a particular level. The 0 to 10 NRS has been translated into many languages. A few translations are seen in Figure 3-6 (p. 60). Further, there is preliminary evidence that a 0 to 10 NRS (presented with a visual) has higher reliability in illiterate patients when compared to the VAS or a verbal rating scale (such as no pain, mild, moderate, severe, unbearable) (Ferraz, Quaresma, Aquino, et al., 1990). Results are difficult to generalize because the study was conducted only with Portuguese patients. Figure 3-6 Translations of 0-10 numerical rating scale. Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale: Work on the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (henceforth referred to as the FACES scale) began in 1981 by Donna Wong, a nurse consultant, and Connie Morain Baker, a child life specialist, who were working in a burn unit. In 1988, Wong and Baker published a study of 150 children aged 3 to 18 years. The FACES scale was presented in a circular format and was compared to five other scales: (1) a simple descriptive scale with numbers assigned to five adjectives on a horizontal line; (2) a numeric scale with the numbers 0 to 10 on a horizontal line; (3) a five-glasses scale in which the glasses contained varying amounts of water, ranging from no water to a full glass; (4) a chips scale using five white plastic chips; and (5) a color scale that included six colors. This study demonstrated the initial reliability and validity of the FACES scale, and no single scale demonstrated superior validity or reliability. The most preferred scale was the FACES scale. Because the FACES scale was presented in a circular format, the results of this study are difficult to compare with those of the numerous other studies in which these faces and other faces scales are presented to children and adults in a horizontal format. Other information concerning the development of this scale and its use in children is available at http://www.mosbysdrugconsult.com/WOW/faces.html and http://www.mosbysdrugconsult.com/WOW/facesStatisticalAnalysis.html. Unfortunately, several studies of reliability and validity listed at this website are unpublished. The FACES scale was developed for use with children, but is it appropriate for some adults? Indeed, some studies of adults have revealed that they often prefer the faces scales to other scales. For example, in one study of 267 adults, the FACES, VAS, and NRS were compared, and the FACES was preferred (Carey, Turpin, Smith, et al., 1997). In another study of children and their parents, a comparison of five faces scales revealed that the parents as well as the children preferred the FACES scale (Chambers, Giesbrecht, Craig, et al., 1999). The cartoon-like features of this scale seem to contribute to this preference. The high preference for the FACES scale is one reason for combining the FACES scale with the NRS to give adults a choice in pain rating scales (see Figure 3-3, p. 56). Of the various faces scales, the FACES scale is currently probably the most widely used in both children and adults in the United States. The FACES scale meets many of the criteria for selecting a pain rating scale for use in clinical practice (see Box 3-2, p. 54). The faces do not depict age, gender, or culture. The FACES scale has been translated into several languages (Figure 3-7, pp. 66-67; translations are available at http://www.mosbysdrugconsult.com/WOW/faces Translations.html). It is therefore appropriate for patients of various cultures. It is often preferred by adults when they compare it to other scales. It is quickly explained and easily scored, easily and quickly understood, well-liked by clinicians and patients, and inexpensive to duplicate. Figure 3-7 Translations of Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale. From Hockenberry, M. J., Wilson, D., & Winkelstein, M. L. (2005). Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 7, St. Louis, Mosby, p. 1259. Used with permission. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 66-67, St. Louis, Mosby. Permission to use the FACES scale for purposes other than clinical practice can be obtained at http://www1.us.elsevierhealth.com/FACES/. The NRS is in the public domain. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Faces Pain Scale-Revised: The FPS-R is a modification of a scale with seven faces developed by Bieri, Reeves, Champion, and others (1990). A scale with seven faces does not adapt well to the 0 to 10 metric used by the majority of pain scales. The revised scale has six faces, so it is easily presented with the 0 to 10 metric (see Figure 3-4, p. 57) (Hicks, von Baeyer, Spafford, et al., 2001). Although numbers beneath the faces are not used when the scale is shown to young children, they are developmentally appropriate to use with adults. In fact by the age of eight years most children are able to use a 0 to 10 scale (Spagrud, Piira, von Baeyer, 2003). • Cognitively impaired and intact older adults who were Asian, African-American, or Hispanic. The last two groups preferred the FPS-R. • Cognitively intact elderly Spanish patients; most preferred the FPS-R. • Cognitively intact Chinese adults ranging in age from 18 to 78 years old; almost half preferred the FPS-R; the FPS-R had a low error rate. These studies ensure that the FPS-R meets some of the criteria for selecting a pain rating scale for use with adults in daily clinical practice (see Box 3-2, p. 54). Research establishes it as being reasonably valid and reliable in children and adults. It is developmentally appropriate not only for children but also for adults as young as 18 years and for cognitively intact and cognitively impaired elderly. It is easily understood and well liked by patients. It has demonstrated appropriateness for patients of various cultures, such as minorities, Chinese, and Spanish. Further, the tool is available in approximately 30 languages (Figure 3-8). It is inexpensive and easily explained, scored, and recorded. Figure 3-8 Translations of Faces Pain Scale-Revised. From Hicks, C. L, von Baeyer, C. L., Spafford, P. A., et al. (2001). The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain, 93, 173-183. As appears in Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 69-85, St. Louis, Mosby. Permission to use the FPS-R for purposes other than clinical practice or research can be obtained by e-mailing IASPdesk@iasp-pain.org. This figure has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the Study of Pain. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. • at regular intervals after a management plan is initiated, • with each new report of pain; and • at an appropriate interval after each pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic intervention, such as 15 to 30 minutes after parenteral drug therapy or 1 hour after oral administration of an analgesic” (p. 28). It is not unusual for clinicians to claim that patients cannot use pain rating scales. However, even in cognitively impaired elderly patients in nursing homes, 83% who report pain are able to use at least one type of pain rating scale (Ferrell, Ferrell, Rivera, 1995). Another study that included older cognitively impaired minority patients used a verbal descriptor scale (no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, severe pain, extreme pain, and most intense pain imaginable), a 0 to 10 NRS, a FPS-R, and an Iowa Pain Thermometer (Figure 3-9, p. 87) and found that all these scales were relatively easy for these patients to use (Ware, Epps, Herr, et al., 2006). Therefore, most adolescents and adults who are not cognitively impaired should be able to learn to use a pain rating scale. It is simply a matter of having a plan that ensures that when patients are admitted to clinical settings, someone is responsible for teaching all patients about the pain rating scale, having patients demonstrate their understanding of it, and documenting this in the records. The steps for teaching the 0 to 10 NRS are in Box 3-4 on p. 86. Steps 1, 2, and 3 provide information; steps 4 and 5 ask the patient to demonstrate understanding of the information; and Step 6 focuses on the goals for comfort and function/recovery. Along with each step are specific examples of what may be said to the patient and family. A teaching brochure titled “Understanding Your Pain: Using a Pain Rating Scale” is patterned after the steps in Box 3-4 and is available at www.endo.com. How much pain is too much pain? When clinical practice guidelines first began to be published, the need for a goal was recognized. One of the first guidelines stated: “Determine the level of pain above which adjustment of analgesia or other interventions will be considered” (Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel, 1992, p. 7). The primary reason for using pain rating scales is to evaluate the effectiveness of the pain treatment plan. To do this, it is essential to set goals, as described in Box 3-4, Step 6. In a review of studies of primary care physicians’ goals for pain treatment, goals for pain relief were the single best predictor of the quality of pain management (Green, Anderson, Baker, et al., 2003). The patient’s comfort-function goal should be visible on all records where pain ratings are recorded, such as bedside flow sheets. Whether the goal has been achieved or not should also be routinely included at change-of-shift hand-off reports. If the pain rating is below the goal, documentation should show which efforts were made to achieve the desired goal. For outpatient pain management, a diary or flow sheet kept by the patient (discussed later; see Form 3-11, p. 116) is one way to document and make visible progress toward goals. Establishing comfort-function goals for individual patients and holding clinicians accountable for attempting to achieve those goals may help clinicians to avoid basing pain-management decisions on their own biases. Form 3-11 From Pasero, C., & McCaffery M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 116, St. Louis, Mosby. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Research helps to guide the process of setting a comfort-function goal by suggesting that certain pain levels are more than a patient should attempt to tolerate. The findings of several studies of different cultures have found that on a 0 to 10 NRS, pain ratings of 5 or more interfere significantly with daily function (Cleeland, 1984; Cleeland, Gonin, Hatfield, et al. 1994; Serlin, Mendoza, Nakamura, et al., 1995). The data from several countries (Philippines, France, China, and the United States) confirmed that pain ratings of 5 or greater were clearly more significant in their functional impact than pain ratings of 4 or less (Cleeland, Serlin, Nakamura, et al., 1997). In a study of 271 patients with AIDS-related pain, ratings on the BPI interference items (see Form 3-2, p. 53) found that patients with pain ratings up to 4 out of 10 reported that pain interfered most with mood and enjoyment of life (Breitbart, McDonald, Rosenfeld, et al., 1996). Patients with pain ratings of 5 or 6 out of 10 reported somewhat higher levels of interference on the BPI items, with pain again interfering most with mood and enjoyment of life. Patients with pain of 7 or more out of 10 reported even greater pain interference on the BPI items, with pain interfering most with walking ability, general activity, and sleep. Another study of 274 patients with AIDS-related pain revealed that higher levels of pain intensity resulted in increased levels of depressive symptoms and psychological distress (Rosenfeld, Brietbart, McDonald, et al., 1996). Thus, as pain intensity increases, it is associated with greater impairment in functional ability and psychologic distress. This information helps in guiding patients who select goals of 4, 5, or 6 out of 10. Such patients need to be cautioned that pain ratings this high may significantly interfere with function. Further, clinicians should ask these patients why they do not want better pain relief. In research in patients with persistent pain, mentioned earlier, almost all patients said that they did not expect pain to diminish to below 4 or 5 out of 10 without excessive interference from medications’ adverse effects (Zelman, Smith, Hoffman, et al., 2004). Patients felt they were trading pain relief for lower function. Clinicians should pursue this problem with patients and determine whether the adverse effects can be managed. If the problem is related to opioids, the addition of other medications such as nonopioids or adjuvants for pain relief can be explored. Or the adverse effects may respond to treatment. If the adverse effect of concern is sedation, patients can be informed that increases in opioid dosages may initially cause significant cognitive impairment but that with stable dosages of opioid this effect usually subsides in about a week (Bruera, Macmillan, Hanson, et al., 1989). If the adverse effect is constipation, a more aggressive bowel regime can be put in place to prevent this effect. (See Section IV for additional information about management of opioid-induced adverse effects.) Minimum Clinically Important Changes: These changes are sometimes referred to as minimal important changes. In the process of adjusting pain treatment plans, such as titrating opioids, to accomplish the comfort-function goal, it is helpful to know how much reduction in pain intensity will be important to patients. A statistically significant decrease in pain intensity may not be meaningful to a patient. Therefore, it is important to look at the degree of reduction in pain that is clinically meaningful from the patient’s perspective. Several studies have found that approximately a 30% reduction in pain intensity in cases of acute or persistent pain is minimally clinically meaningful but that it depends on the baseline intensity of pain (Farrar, Young Jr., LaMoreaux, et al., 2001; Jensen, Chen, Brugger, 2003; Ostelo, Devo, Stratford, 2008; Sloman, Wruble, Rosen, et al., 2006). For example, a clinical reduction of 2 points on the 0 to 10 NRS may have clinical relevance for someone with mild pain but is of little or no relevance to someone with severe pain (Cepeda, Aficano, Polo, 2003). Specifically, a 2-point reduction in pain intensity from 4 to 2 on a 0 to 10 NRS (a 50% reduction) is likely to be meaningful to a patient with mild pain, but a 2-point reduction from 10 to 8 (a 20% reduction) may not be meaningful and may provide “only some relief” to a patient with severe pain.

Assessment Tools

Tools for Initial Pain Assessment

Tools for Initial Overall Pain Assessment

Initial Pain Assessment Tool

Brief Pain Inventory

Pain Intensity Rating Scales

Criteria for Selecting Pain Rating Scales for Use in Daily Clinical Practice

Visual Analogue Scale

Recommended Pain Intensity Rating Scales

*Courtesy of Pain-Management Committee, St. Francis Medical Center, Honolulu, NY.

†Compiled by Josephine Musto, St. Vincent’s Hospital and Medical Center, New York, NY. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 60–65. St. Louis, Mosby. These scales are in the public domain. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

Principles of Using Pain Rating Scales

Teaching Patients and Families How to Use a Pain Rating Scale

Setting the Comfort-Function Goal

Research Related to Setting Comfort-Function Goals

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assessment Tools

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue