Overview

Assessment of the workplace is central to the practice of occupational medicine

‘Risk assessment’ involves identifying hazards and gauging the likelihood of harm, so as to plan risk control measures

Controls follow a hierarchy of effectiveness, with avoidance and substitution (most dependable) at one extreme and measures that rely on employees’ compliance (least dependable) at the other

Sometimes, sophisticated environmental measurements and formal research are needed to identify new hazards or to assess risks

However, simple common sense observations, systematically made and recorded, can go along way towards preventing ill health at work

Understanding of the workplace is as central to the practice of occupational medicine as clinical assessment of the individual patient. It is an essential step in the control of occupational hazards. Moreover, by visiting a place of work, a doctor can appreciate the demands of a job, and thus give better advice on fitness for employment and/or modifications that may assist work after illness (see Chapter 7). Investigations may be prompted in various circumstances (Box 3.1).

Hazard and Risk

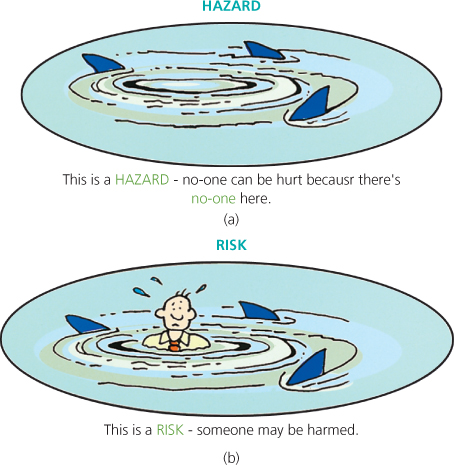

Managing occupational risks to health requires identification of the ‘hazards’ in a workplace, and then assessment of the ‘risks’ that they pose (Figure 3.1). A hazardous agent or circumstance has the potential to harm (a hazard of water is drowning); ‘risk’ is the likelihood that the hazard will be realized (nil in a thimbleful of water, high in the open sea). Risk depends on the nature and extent of exposure to the hazardous agent or situation. The art of risk assessment (which is a legal requirement in many circumstances—see Chapter 5) is to identify and characterize material risks to health that may require control. In doing this, account must be taken of the seriousness of potential outcomes as well as their likelihood (a low chance of death would merit more attention than a high probability of light bruising). Identification of hazards may be assisted by manufacturers’ safety data sheets, but assessment of risk requires an understanding of how work is conducted and of levels of exposure.

Figure 3.1 Hazards and risks. a) A hazard is a potential adverse effect of an agent or circumstance. Risk is the probability that harm will occur. Risk assessment involves identifying hazards and characterizing the associated risks. b) After listing the hazards, it is important to consider who might be exposed and in which job(s); how likely this is under the prevailing circumstances of the work (including any precautions followed); and the magnitude of expected exposures and their likely impact on health (the risks to health). (See also HSE 2006.).

Inspecting the Workplace

One method of assessment is direct inspection of the workplace. Inspections often take the form of a structured ‘walk-through’ survey.

Planning a Walk-Through Survey

Industrial processes are complex, and hazards are plentiful. How should a survey be conducted? The arrangements and context are important. The initial visit should be by appointment (an unannounced snap inspection may be revealing, but is practicable only for a health and safety professional who has an established relationship of trust with the employer). Arrangements should be checked beforehand, as pre-planning saves time.

The survey should be structured, but the precise way it is organized is less important. At least three approaches are commonly adopted:

- Following a process from start to finish—from raw materials in to finished goods going out. What hazards occur at each stage? What are the risks? How should the risks be controlled? Do the controls actually work? This process-focused assessment aids basic understanding of the work and its requirements.

- Auditing a single category of activity or hazard (such as dusty or noisy procedures or manual handling)—wherever it occurs within the organization. Does the control policy work every where, or are there special problems or poor compliance (higher risks) in certain groups of workers or sites? This audit trail or hazard-focused assessment is useful for introducing and monitoring new policies.

- Detailed inspection site by site (Box 03.0002)—What are the hazards in this particular site? How are the potential risks controlled? The inspection moves on only when the geographical unit of interest has been thoroughly inspected. This site-focused approach is appreciated by shop stewards and workers’ representatives with local ownership of the problem. They may accompany the inspection and often provide insight into working practices and problems not apparent during the visit.

- be accompanied by someone with responsibilities for safety

- see someone who can explain the process

- have a chance to see representative activities

What to Cover in a Walk-Through Survey

The aim is to determine whether risks are acceptable, taking into account both the likelihood of an adverse outcome and its seriousness; or whether further control measures are required, and, if so, what these should be (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Simple Checklist of Control Measures

| Option | Key questions to ask | Possible controls* |

| Avoidance or substitution | Does the material need to be used at all or will a less noxious material do the job? | Try using a safer material if one exists |

| Material modification | Can the physical or chemical nature of the material be altered? | Can it be obtained as a granule or paste rather than powder? Can it be used wet? |

| Process modification | Can equipment, layout, or procedure be adapted to reduce risk? | Can it be enclosed? Can dust be extracted? If material is poured, tipped, or sieved, can the drop height be lowered? |

| Work methods | Can safer ways be found to conduct the work? Can it be supervised or monitored? Do workers comply with methods? | Avoid dry sweeping (it creates dust clouds). Be careful with spills. Segregate the work; conduct it out of hours |

| Personal protective equipment | Have all other options been considered first? Is it adequate for purpose? Will workers wear it? | Provision of mask, visor, respirator, or breathing apparatus suitable for intended use |

* A dust hazard is used as an example (see also Aw et al., 2006).

Health and safety professionals use checklists to ensure that all the major types of hazard are considered and to ensure that the control options to reduce risks are fully explored. They seek to verify that these options have been considered in an orderly hierarchy:

- Since prevention is better than cure, can the hazard be avoided altogether? Or can a safer alternative be used (substituted) instead?

- Otherwise, can the process or materials be modified to minimize the problem at source? Can the process be enclosed? Or operated remotely? Can fumes be extracted close to the point at which they are generated (local exhaust ventilation)?

- Have these ideas been reviewed before issuing ear defenders, face masks or other control measures that rely on workers’ compliance (‘Do not smoke,’ ‘Do not chewy our fingernails,’ ‘Lift as I tell you to’)?

- A realistic strategy should always place more reliance on control of risk at source than on employees’ personal behaviour and discipline.

What the Survey May Find

The purpose of the walk-through survey is to be constructively critical. When good practices are discovered these should be warmly acknowledged. Faulty practices arise from ignorance as often as from cutting corners.

We have visited workplaces where expensive equipment, provided to extract noxious fumes from the worker’s breathing zone, was switched off because of the draught, or directed over an ashtray to extract cigarette smoke rather than the fumes, or obstructed by bags of components and Christmas decorations.

Local exhaust ventilation may be visibly ineffective –the fan may be broken, the tubing disconnected, the direction of air flow across rather than away from the worker’s breathing zone; protective gloves may have holes or be internally contaminated; the rubber seals of ear defenders may be perished with age. Poor house keeping may cause health risks (Figures 3.2–3.6). There may be no audit to check that items of control equipment are maintained and effective. Simple common-sense observations, systematically made and recorded, will go a long way towards preventing ill health at work.

Figure 3.2 Workplace inspection aids understanding of the job demands and risks. This stonemason is exposed to hand-transmitted vibration, noise and silicaceous dust.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree