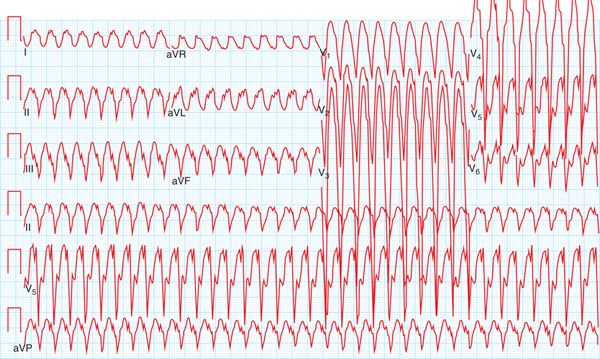

FIGURE 54-1 Patient’s presenting VT upon arrival of EMS, recorded at 260 ms.

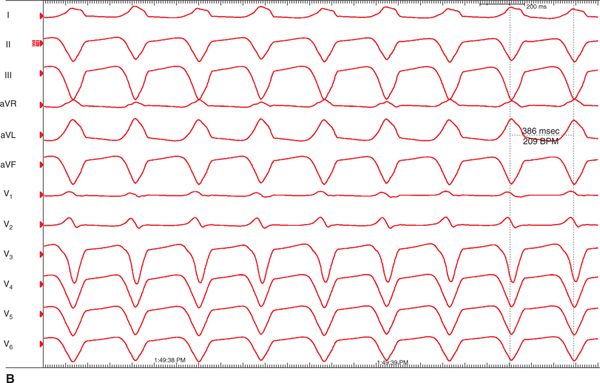

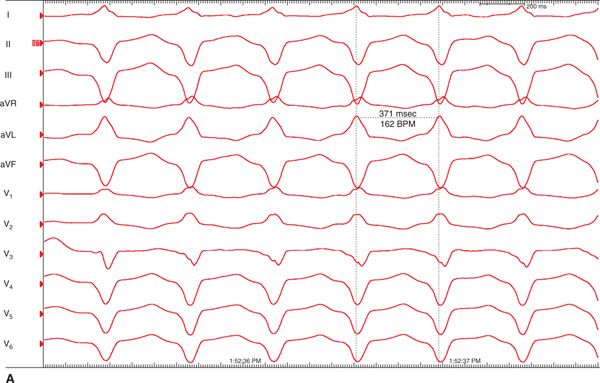

FIGURE 54-2 Ventricular tachycardia recurred in the emergency department, recorded on 12-lead ECG, revealed LBBB, superior axis morphology.

FIGURE 54-3 T-wave inversions in leads V1 to V4, a major diagnostic criterion for ARVD/C.

FIGURE 54-4 Cardiac MRI notes a dilated RV with akinesis of the base of the RV. Outpouching of the angle of the RV (denoted by arrow) is a classic MRI finding in ARVD/C.

FIGURE 54-5 During electrophysiology study and ablation two VTs were noted: (A) LBBB superior and (B) LBBB, indeterminate axis.

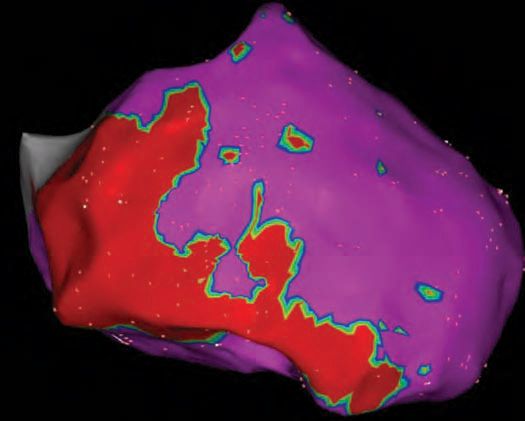

FIGURE 54-6 Epicardial three-dimensional voltage mapping created on a CARTO system demonstrating significant RV scar from the anterior to inferior RV extending from base to apex. Late potentials were also clearly present on the epicardial sites of scar.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ARVD/C

ARVD/C is an inherited cardiomyopathy characterized by fibrofatty replacement of the myocardium, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and ventricular dysfunction (right > left ventricle). The disease has a prevalence estimated 1 per 5000, though some reports estimate the real prevalence could be as high as 1 in 1000 due to under-recognition. Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the first manifestation in up to 50% of cases.1

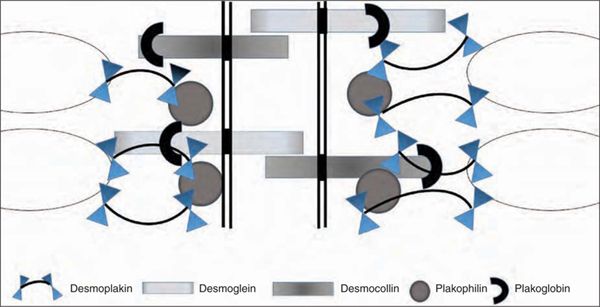

Subsequent to the discovery of pathogenic mutations in the desmosomal genes (Table 54-1) in families with ARVD/C, the disruption of the desmosomal structure as the key factor in many cases leading to ARVD/C development has been widely accepted in the field.2,3 The desmosomes not only provide structural attachment among cells, they also mediate intracellular signal transduction pathways as part of the intercalated disc4 (Figure 54-7). The specific mechanism by which the mutations in these genes may translate into the variety of disease expression seen clinically, however, has been the subject of many hypotheses.

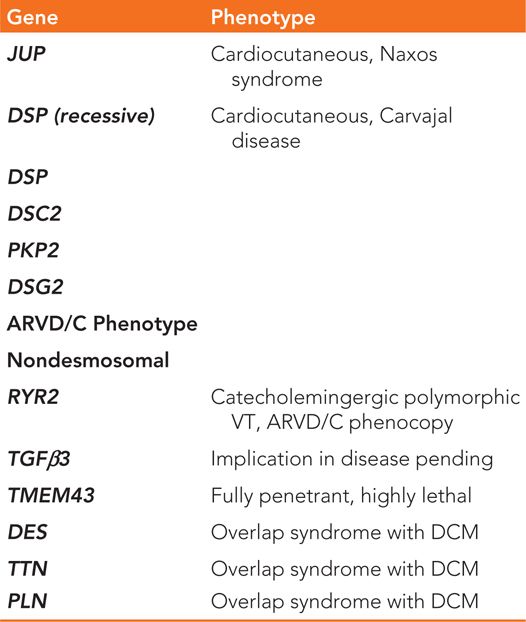

TABLE 54-1 Genes Currently Associated with ARVD/C

FIGURE 54-7 Schematic representation of the structure of the cardiac desmosome and intercalated disc. The desmosome links in the intermediate filament of the heart muscle (oval) and is embedded in the cell membrane (vertical line).

Proposed mechanisms include that desmosomal mutations disrupt a triad between gap junction, voltage-gated sodium channel complex, and desmosomes, or intercalated disc.5 It is thought that the desmosomal proteins may have two roles: signal molecules that may promote cardiac myocyte apoptosis and also structural connections in the gap junction.6 Disruption of the desmosomes leaves the cardiomyocytes unable to handle mechanical stress, which leads to the cells being ripped apart and cell death.7 Evidence in mouse models and new clinical evidence from patient data have indicated that strenuous exercise in ARVD/C patients may play a pivotal role in advancing disease as mechanical stress of stretch in the heart disrupts these weakened connections.8,9

DIAGNOSIS

An ARVD/C diagnosis is made by meeting a set of major and minor diagnostic criteria (Table 54-2). There is no gold-standard test or criterion in the diagnostic criteria that is pathognomonic for ARVD/C, and a diagnosis of ARVD/C should not be made based on a single clinical test. The first diagnostic criteria for ARVD/C were published in 1994.10 Over time, however, they were shown to lack sensitivity for the identification of early/mild disease, and they did not include the newly discovered utility of genetic testing for ARVD/C. Revised diagnostic criteria were proposed by a working task force in 2010.11 In the revised criteria, a definite diagnosis of ARVD/C is fulfilled by two major or one major and two minor criteria, or four minor criteria. An important specification is that criterion must be from separate categories. A borderline diagnosis is made by one major and one minor, or three minor criteria, and a possible diagnosis by one major or two minor criteria.

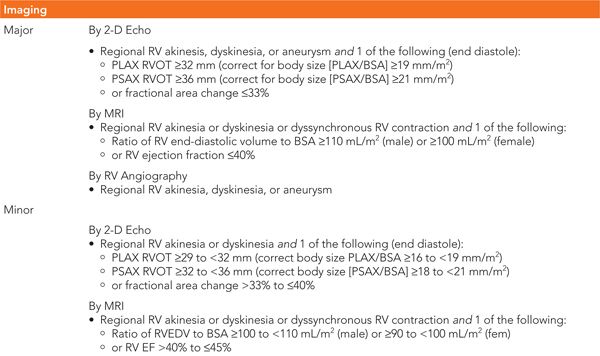

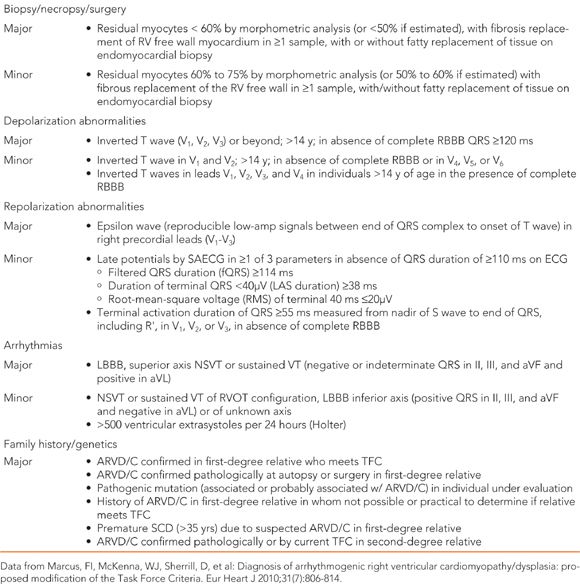

TABLE 54-2 Revised 2010 Task Force Criteria for Diagnosis of ARVD/C

The diagnostic criteria are based on assessment of the extent of ventricular structural alterations and dysfunction, tissue characterization on biopsy, repolarization and depolarization abnormalities on ECG and signal averaged ECG (SAECG), arrhythmias and ventricular ectopy, and family history and genetic criteria. Recommended noninvasive testing when evaluating for ARVD/C includes 12-lead ECG, SAECG, echocardiogram, cardiac MRI, exercise stress testing, and ambulatory ECG monitoring (24-hour Holter monitoring). Cardiac MRI has a much higher specificity and sensitivity for diagnosis than echocardiogram, especially in detecting early disease.11 The revised diagnostic criteria remain limited in that it does not include those with left sided dominant disease. Left dominant disease in ARVD/C (LDAC) can be differentiated from DCM by a marked electrical instability that exceeds the degree of dysfunction. Up to one-third of genotyped individuals with an LDAC presentation had an identifiable pathogenic desmosomal mutation.12

Microscopic evaluation of samples at necropsy, surgery, or biopsy may reveal interstitial and replacement fibrosis and fatty infiltration. Pure fat infiltration of the RV is reported in >50% of normal hearts in elderly patients.13 Furthermore, those with exclusively fatty infiltration of the RV on autopsy were older, lacked any family history of sudden cardiac death (SCD), and died during nonstrenuous activities. These studies have led to the conclusion that fibrofatty histology and not solely adipose replacement is associated with ARVD/C.14 Autopsies and endomyocardial biopsy as part of a diagnosis of ARVD/C should be evaluated carefully.

Family history is an important component of evaluation for ARVD/C. First-degree relatives of an individual diagnosed with ARVD/C are at 50% risk also to inherit the genetic predisposition to ARVD/C. A negative family history does not exclude the possibility of ARVD/C. Up to 50% of ARVD/C index cases have no family history of SCD or cardiomyopathy. Families should also be cautioned regarding the high variable expressivity of ARVD/C. Even within the same family and same known pathogenic mutation, severity of disease and type of presentation may vary greatly.1

Differential diagnosis in ARVD/C includes idiopathic premature ventricular contractions or ventricular tachycardia, myocarditis, and cardiac sarcoidosis. Patients presenting with ventricular arrhythmias should be first evaluated for more common idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) ectopy or VT.1 Misdiagnosis is common in ARVD/C. Most commonly, over-read and over-reliance on cardiac MRI is part of the error.15 There are also other diseases that may mimic ARVD/C. Many patients who present with right-sided cardiac sarcoidosis meet diagnostic criteria for ARVD/C. This can be differentiated in the involvement of the septum in the disease, presence of high-grade atrioventricular conduction block on ECG at presentation, which is unusual in ARVD/C, and rapid progression of disease.16,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree