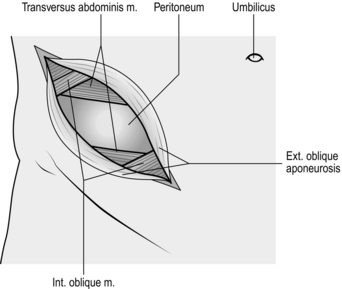

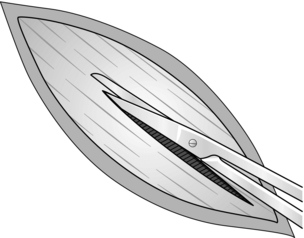

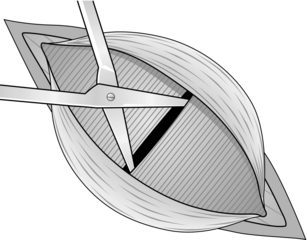

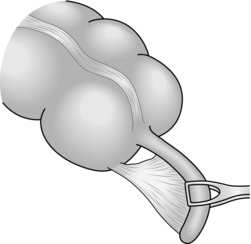

7 1. Acute appendicitis is essentially a clinical diagnosis. A detailed history and careful examination of the patient carry more weight in making the diagnosis than embarking on radiological investigations, although these investigations can be useful to rule out alternative diagnoses. 2. Although appendicectomy is still the most common reason for laparotomy, remember the following: 3. Tend to treat conservatively a patient with symptoms for 5 or more days in whom you find a mass in the right iliac fossa. Give a 7-day course of intravenous antibiotics such as co-amoxiclav and metronidazole, withhold oral feeding and replace fluid intravenously. Mark the extent of the mass on the abdominal wall. Perform an ultrasound or CT scan to exclude the presence of a large abscess that can be drained percutaneously. Carefully monitor the patient and perform an operation only if: 4. Some surgeons carry out diagnostic laparoscopy whenever they suspect appendicitis, proceeding to laparoscopic appendicectomy if the diagnosis is confirmed. 5. Avoid removing a normal appendix incidentally during other operations, such as cholecystectomy. It is a possible cause of complications such as wound infection and subsequent adhesive intestinal obstruction. 1. Wound infection is the most common complication following operation for acute appendicitis, so routinely give 500 mg of metronidazole and a broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g. co-amoxiclav) intravenously at induction of anaesthesia. 2. In patients with clinically severe acute appendicitis who are demonstrating signs of systemic sepsis, commence intravenous metronidazole and a broad-spectrum antibiotic as soon as the decision to operate is made. 3. Patients who have a perforated appendix require a full 5-day course of broad-spectrum antibiotic and metronidazole. 1. As a routine employ a Lanz incision in a skin crease. This modification of the gridiron incision transversely crosses McBurney’s point – the junction of the middle and outer thirds of a line joining the anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus. The incision starts 2 cm below and medial to the right anterior, superior iliac spine and extends medially for 5–7 cm. It may be possible to site it lower in a young girl so that the scar lies below the waistline of a bikini. 2. Alternatively, use the traditional gridiron incision, 5–8 cm long, in line with the external oblique fibres if you anticipate the need to extend the exposure (Fig. 7.1). The incision crosses McBurney’s point at right-angles to the spino-umbilical line, one-third above, two-thirds below. If necessary, the external oblique muscle and aponeurosis can be split in both directions and the internal oblique and transversus muscles can be cut to convert the incision into a right-sided Rutherford Morrison incision. 3. If appendicitis is one of a number of likely diagnoses, opt for a lower midline incision. 1. Incise the skin cleanly with the belly of the knife. Divide the subcutaneous fat, Scarpa’s fascia and subjacent areolar tissue to expose the glistening fibres of the external oblique aponeurosis. In the gridiron approach these fibres run parallel to the skin incision. 2. Stop the bleeding. Incise the external oblique aponeurosis in the line of its fibres. Start with a scalpel, then use the partly closed blades of Mayo’s scissors (Fig. 7.2) while your assistant retracts the skin edges. 3. Retract the external oblique aponeurosis to display the fibres of the internal oblique muscle, which run at right-angles. Split internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, using Mayo’s straight scissors (Fig. 7.3). Open the blades in the line of the fibres and use both index fingers to widen the split. Provided the scissors are not thrust in violently, the transversalis fascia and peritoneum are pushed away unopened. 4. Stop the bleeding. Have the muscles retracted firmly to display the fused transversalis fascia and peritoneum. 5. Pick up a fold of peritoneum with toothed dissecting forceps and grasp the tented portion with artery forceps. Release the dissecting forceps and take a fresh grasp to ensure that only the peritoneum is held. Make a small incision through the peritoneum with a knife. Allow air to enter the peritoneal cavity, so that the viscera fall away. Use scissors to enlarge the hole in the line of the skin incision. Now protect the wound edges with swabs or skin towels. 1. Look. Is there any free fluid or pus? If so, take a specimen for microscopy and culture. 2. Find the caecum, identify a taenia and follow it distally to the base of the appendix. Insert a finger and lift out the appendix by pushing from within, not by pulling from without. 3. If the appendix is not evident, push your index finger posteriorly until it comes to lie on the peritoneum over the psoas muscle. Then, maintaining contact with the posterior peritoneum, draw your finger to the right until it can go no further. The caecum should now lie between the ‘hook’ of your finger and the right limit of the iliac fossa, and may be gently pushed out onto the surface. In some cases you may need to mobilize the caecum by incising the parietal peritoneum in the paracolic gutter, in order to raise the caecum on its mesentery, especially if the appendix is adherent retro-caecally. If the caecum is not evident, remember that it sometimes lies quite high, under the right lobe of the liver. 4. Confirm the diagnosis: the appendix, or more usually its tip, is swollen, congested, inflamed, even gangrenous, often with fibrin deposition, turbid fluid or frank pus. 1. Mobilize the appendix from base to tip by gently moving or peeling away adherent structures. Remember that the artery enters from the medial aspect. If the tip is adherent, improve the view. Do not dissect blindly. If necessary, extend the incision. Apply Babcock’s tissue forceps to enclose, but not grasp, an uninflamed portion of the appendix, to hold it so you can view the mesentery against the light and identify the artery. 2. Pass one blade of the artery forceps through the mesoappendix and clamp the vessels (Fig. 7.4). If it is thickened, take the mesoappendix in two bites. Divide the mesoappendix distal to the clamp and ligate the vessel gently but firmly with 2/0 Vicryl or similar material, ignoring the slight back bleeding from the distal cut end. 3. Crush the base of the appendix with a haemostat then replace the clamp 0.5 cm distal to the crushed segment. Ligate the crushed segment with 2/0 Vicryl. Apply a haemostat to the ligature ends after trimming them. 4. Cut off the appendix just distal to the haemostat. 5. There is no need to invaginate the appendix stump by use of a purse-string suture, nor should the appendix stump be diathermized.

Appendix and abdominal abscess

OPEN APPENDICECTOMY

Appraise

Young children and the elderly may have atypical presentations of appendicitis and also have a higher mortality and morbidity from this condition.1

Young children and the elderly may have atypical presentations of appendicitis and also have a higher mortality and morbidity from this condition.1

Female patients may have a gynaecological cause for pain and tenderness in the right iliac fossa rather than appendicitis. Order a pelvic ultrasound scan and consider carrying out a diagnostic laparoscopy in such cases.

Female patients may have a gynaecological cause for pain and tenderness in the right iliac fossa rather than appendicitis. Order a pelvic ultrasound scan and consider carrying out a diagnostic laparoscopy in such cases.

There is good evidence that in female patients, appendicitis, even when perforated, does not adversely affect fertility, so you need not perform a mandatory appendicectomy in equivocal cases.2

There is good evidence that in female patients, appendicitis, even when perforated, does not adversely affect fertility, so you need not perform a mandatory appendicectomy in equivocal cases.2

Although elderly patients do develop appendicitis, consider other pathology such as perforating carcinoma of the caecum and diverticulitis, which may mimic its presenting features. In case of doubt, use a midline incision so you can carry out a full examination of the peritoneal cavity.

Although elderly patients do develop appendicitis, consider other pathology such as perforating carcinoma of the caecum and diverticulitis, which may mimic its presenting features. In case of doubt, use a midline incision so you can carry out a full examination of the peritoneal cavity.

Computed tomography (CT) is the most sensitive imaging technique for diagnosing appendicitis.3 In view of the radiation dose, reserve this investigation for those in whom a negative laparotomy represents an unjustifiable risk.

Computed tomography (CT) is the most sensitive imaging technique for diagnosing appendicitis.3 In view of the radiation dose, reserve this investigation for those in whom a negative laparotomy represents an unjustifiable risk.

PREPARE

Access

Opening the abdomen

Assess

Action