Appendectomy: Single-Incision Laparoscopic Surgery Technique

Reshma Brahmbhatt

Mike K. Liang

DEFINITION

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) appendectomy is defined as laparoscopic removal of the appendix using a single skin incision. The entire procedure, including an intracorporeal appendectomy, is performed laparoscopically. This is in contrast to other methods of single-incision appendectomy, which use a single port/incision for dissection but then proceed to pull the appendix out of the incision and essentially perform an open appendectomy. The addition of an additional port distant from the single incision (usually the suprapubic region) is called a SILS plus one (SILS +1) appendectomy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for acute appendicitis in the healthy adult patient includes gastroenteritis, colitis, cystitis/pyelonephritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and diverticulitis.

Female patients have an expanded differential diagnosis, which can include pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian pathology, ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis, and mittelschmerz.

Pediatric patients can have acute mesenteric adenitis, especially following an upper respiratory tract illness, that can mimic acute appendicitis.

Immunosuppressed patients may have opportunistic infections that present in a similar fashion to acute appendicitis, and consideration should be given to a full infectious workup.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

For patients to undergo SILS appendectomy, they must be candidates for traditional laparoscopic appendectomy. Patients with previous midline abdominal surgery or large ventral hernias may present a relative contraindication to SILS appendectomy due to adhesions and potential difficulty with abdominal entry. A thorough history and physical examination is necessary to carefully select patients for SILS appendectomy. Pediatric, elderly, and pregnant patients are appropriate for SILS appendectomy.1 Absolute and relative contraindications to SILS appendectomy are listed in Table 1.

A thorough history should be performed, including location and duration of symptoms, previous history of similar episodes, and detailed past medical and surgical history. A short (1 to 2 days) history of nausea/vomiting, anorexia, fevers, and periumbilical or right lower quadrant pain in a previously healthy patient is suspicious for acute appendicitis. A longer (5 to 7 days) history of nausea/vomiting, malaise, fevers, and right lower quadrant pain may be consistent with perforated appendicitis and abscess formation.

A complete physical examination should be performed. Particular attention should be paid to the patient’s vital signs and abdominal examination. The patient will often be ill appearing and prefer to lie still.

Classic abdominal findings of appendicitis include tenderness in the right lower quadrant with localized guarding and rebound. The abdomen is often soft with minimal to no distention.

Female patients of childbearing age should undergo a bimanual vaginal examination to evaluate for gynecologic conditions, such as pelvic inflammatory disease or adnexal abnormalities, which may mimic appendicitis.

Atypical presentations of acute appendicitis can include suprapubic pain, right flank pain, and right upper quadrant pain, depending on where the appendix may be located.

Anatomic variations may cause pain in the right flank (retrocecal appendix) or even the absence of abdominal pain (pelvic-lying appendix). Right-sided pain on rectal examination may point toward an appendix hanging in the pelvis.

It is also important to note that with very early appendicitis, the patient will often have mild (or even absent) signs and symptoms. These clinical variations should be kept in mind while evaluating the patient for acute appendicitis.

Table 1: Absolute and Relative Contraindications to Single-Incision Laparoscopic Surgery Appendectomy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard laboratory studies ordered in the evaluation of acute appendicitis include a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel or electrolytes, and urinalysis and urine pregnancy test.

An elevated white blood cell count suggests an inflammatory response such as appendicitis.

Electrolyte derangements due to dehydration or vomiting should be corrected prior to surgical management.

A urinalysis may show a urinary tract infection or cystitis to be the source of the patient’s symptoms rather than appendicitis; however, identifying leukocytes in the urine is not uncommon with acute appendicitis.

A positive urine pregnancy test should prompt further evaluation of another diagnosis (such as ruptured ectopic pregnancy) and will affect the medications and anesthesia used during the procedure.

Clinical scoring systems, such as the Alvarado score or the appendicitis inflammatory response score use various laboratory and clinical findings to assess a patient’s likelihood of having acute appendicitis.2, 3

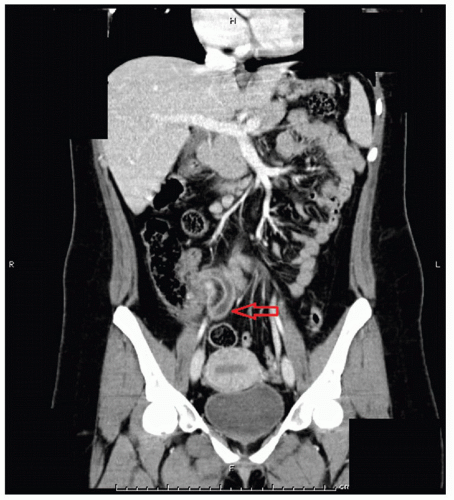

Computed tomography (CT) is the most ordered radiologic study in the evaluation of acute appendicitis. The scan should be ordered as a CT abdomen/pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral or rectal contrast.

CT findings consistent with appendicitis include appendiceal dilation, failure of appendiceal opacification with oral or rectal contrast, presence of a fecalith, periappendiceal fat stranding and enhancement, and pelvic free fluid. CT is excellent in visualizing perforated appendicitis with an abscess and should be considered in any patient where the diagnosis of complicated appendicitis is entertained. Additionally, CT can provide information on other intraabdominal and pelvic structures/pathology (FIG 1).

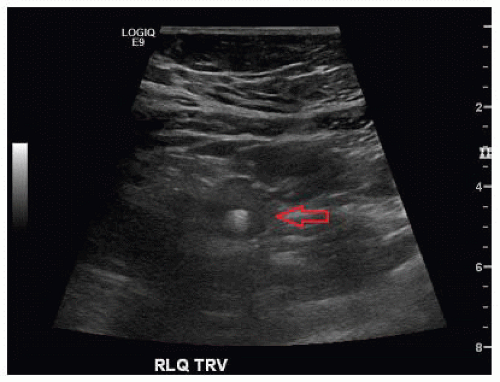

Transabdominal ultrasonography can be used to evaluate for appendicitis as a nonradiating alternative to CT scans. Findings consistent with appendicitis include a thickened appendiceal wall, appendiceal dilation, identification of a fecalith, periappendiceal fluid, and a “target sign.” Limitations to ultrasonography include operator dependence and difficulty in appendiceal visualization in patients with higher body mass index (BMI) (FIG 2). Ultrasonography is most often used in children and pregnant patients. Focused magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used in specific cases as an alternative to CT scan and ultrasound. Pregnant women and children may benefit from this nonradiating imaging modality, but MRI may not be as readily available as ultrasound and CT scan in all centers. The need for MRI should be evaluated on a caseby-case basis.

Women of childbearing age may require evaluation of their adnexal structures via CT scan or transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasonography to rule out differential diagnoses.

In adult male patients with a classic presentation of appendicitis, radiologic studies are not necessarily indicated and are used only at the discretion of the surgeon.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative antibiotics, with gram-negative and anaerobic coverage, should be administered before the incision is made.

A Foley catheter should be placed to ensure bladder decompression.

Patients with large midline laparotomy scars or periumbilical hernia repairs may have significant adhesions or prosthetic material at the level of the umbilicus, making safe abdominal entry potentially difficult. The surgeon should use his or her discretion at proceeding with a SILS appendectomy in these particular patients and should have a low threshold for adding additional ports (SILS +1 appendectomy) for improved exposure and visualization.

Positioning

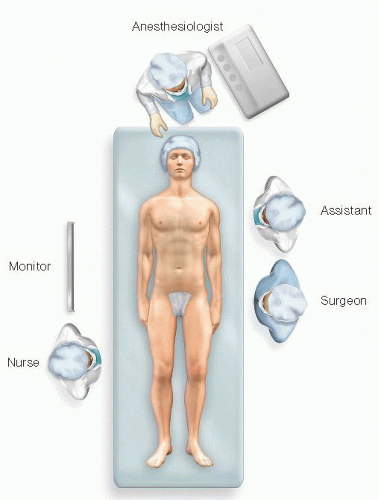

SILS appendectomy is performed from the left side of the patient, similar to traditional laparoscopic appendectomy. The patient should be positioned in a supine position, with the left arm tucked to provide adequate space for the surgeon and the assistant (FIG 3).

The patient’s abdomen should be prepped and draped from the xiphoid to the pubis, allowing for possible conversion to a traditional laparoscopic or open appendectomy if indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree