Appendectomy: Open Technique

James Suliburk

David Berger

DEFINITION

Open appendectomy is defined as removal of the appendix via an incision in the abdominal wall without use of a camera. Prior to laparoscopy, it was the most commonly performed emergency general surgery operation in the United States.

Open appendectomy has been replaced in frequency by laparoscopic appendectomy as the most common emergency general surgery operation performed.

Laparoscopic appendectomy is not always possible, and an open approach may be preferred in patients who have had extensive abdominal or pelvic surgery. Additionally, it may be necessary to convert to an open technique from an initial laparoscopic approach due to technical or anatomic reasons. Open appendectomy can also be the preferred approach in patients who are pregnant in which the gravid uterus precludes laparoscopy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Patients presenting with appendicitis may have any number of conditions mimicking the classic right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain of appendicitis. Conditions that have to be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis can be broken down in categories, including the following:

Gastrointestinal: gastroenteritis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, Meckel’s diverticulum, intussusception, cholecystitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, perforated cancers, and perforated peptic ulcers

Gynecologic: ectopic pregnancy, salpingitis, endometriosis, ovarian torsion, tuboovarian abscess

Urologic: urinary tract infection, nephrolithiasis

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients most commonly present with appendicitis between the ages of 10 and 40 years. Approximately 75% of patients will present with pain of less than 24 hours duration. Classically, the pain is described as starting at the umbilicus and then migrating over several hours’ time to the RLQ as the stimulus changes from the visceral to somatic nerves. However, this classic migration is not always present, and nearly 40% of patients will have atypical pain, with only vague abdominal pain or even flank pain.

Atypical pain can frequently be caused by subtle variation in the appendix location with right upper quadrant pain being caused by an anteriorly located appendix on a high-riding cecum, tenesmus triggered by an inflamed appendix tip in the pelvis, and flank pain triggered by a retrocecal appendix.

Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are classically associated with appendicitis but are variably present. Of these, the sequence of having anorexia and/or abdominal pain preceding vomiting is more consistent with appendicitis. When vomiting is the first symptom elicited, the diagnosis of appendicitis is questionable. Diarrhea is fairly nonspecific.

Physical exam findings consistent with appendicitis are dependent on the location of the appendix. Because the appendix may be located anywhere on the cecum, signs are extremely variable. Classic RLQ point tenderness at McBurney point is present in the normal anterior location of the appendix. Rovsing’s sign (RLQ pain when left lower quadrant is pressed) may also be present.

When the appendix is located in a retrocecal position, a positive psoas sign (pain with extension of the right thigh with the patient lying on the left side) can be elicited. When the inflamed appendix is in the pelvis, the classic obturator sign (pain with internal rotation of the flexed thigh in the supine position) may be positive.

Additional tests for subtle peritoneal irritation, including gently shaking the hospital stretcher or having the patient walk, cough, or jump to determine if this exacerbates pain, are nonspecific for appendicitis and simply indicate peritoneal irritation.

Diffuse peritonitis is consistent with ruptured appendicitis and intraabdominal sepsis. These patients usually present with temperature greater than 39°C and tachycardia.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Laboratory studies and radiologic studies can be complementary to history and physical exam in establishing the diagnosis. A mild leukocytosis is generally present. Occasionally, a “left shift” with normal leukocyte count is seen. Fewer than 5% of patients presenting with acute appendicitis will have both a normal white blood cell (WBC) count and no shift.

Urinary analysis may show a few white or red cells but should not reflect bacteriuria.

Serum chemistry testing for amylase and lipase and liver function tests are useful in cases where the history of presentation and physical exam findings are not classic and there is an atypical presentation.

Imaging studies have come to the forefront of appendicitis diagnosis in recent years. Computed tomography (CT) enhanced with intravenous (IV) and enteral contrast is the gold standard for evaluation of appendicitis. Case series differ slightly in their reports, but a reasonable estimation is that CT is 90% sensitive and 95% specific for detection of appendicitis.

Widespread use of CT has been shown to reduce the incidence of negative appendectomy.1 Furthermore, findings of phlegmon or abscess on CT may prompt the surgeon to undertake an alternate approach in treating complex cases of appendicitis with percutaneous drainage and IV antibiotic therapy as the first step of therapy in order to minimize morbidity to the patient.

Ultrasound remains an imaging modality that is operator dependent. In skilled centers, it can be especially helpful in pediatric patients and in early pregnancy.

Plain abdominal radiographs should not be considered routine or mandatory in the specific evaluation of appendicitis but can be used as an initial test in patients presenting with diffuse peritonitis and signs of intraabdominal sepsis.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The bulk of surgical treatment should be discussed in the “Techniques” section. Here, consider indications and other more general concerns, such as discussed in the following sections.

Preoperative Planning

Patients should receive adequate preoperative fluid resuscitation prior to operation in order to restore urine output. This is especially important for patients who show systemic signs of inflammation (systemic inflammatory response syndrome [SIRS]: fever, tachycardia, increased respiratory rate, WBC count ≥12,000/mm3 or ≤4,000/mm3, or >10% bands).

Evidence-based studies clearly indicate that as soon as the decision to operate on the patient is made, IV antibiotics covering facultative, gram-negative, and anaerobic flora should be promptly administered in an effort to reduce surgical site infection (SSI).2 If simple (nonruptured) appendicitis is encountered at operation, there is no benefit in administration of postoperative antibiotics.

Positioning

The patient is positioned on a supine position with the arms extended or tucked depending on surgeon preference. A Foley catheter can be inserted at the surgeon’s discretion.

TECHNIQUES

OPEN APPENDECTOMY FOR PRIMARY TREATMENT OF APPENDICITIS

First Step—Skin Incision

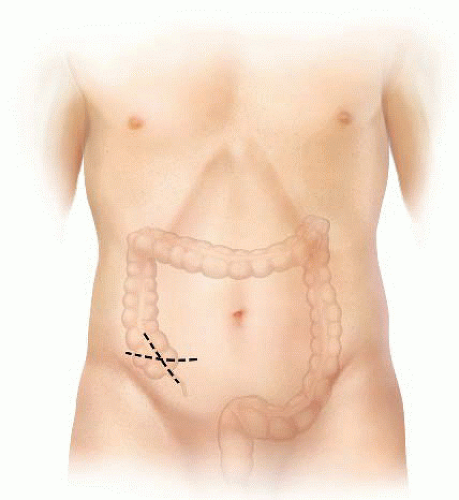

A McBurney (oblique) or Rocky Davis (transverse) incision is made in the RLQ, slightly superior to the point of maximal tenderness found during preoperative exam, and centered on the midclavicular line (FIG 1).

Second Step—Abdominal Wall

There are three muscle layers in the lateral abdominal wall. As these are encountered when entering the abdomen, these are the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transversus abdominis muscles.

Each muscle aponeurosis is cut in the direction of the muscle fibers.

A muscle-splitting technique is used to spread apart each muscle layer along the orientation of the muscle fibers (FIG 2) until the peritoneum is reached.

The peritoneum is then grasped with forceps in order to assure no bowel is adherent and is incised with scissors to enter the abdominal cavity (FIG 3).

An appropriate retractor is placed to enhance operative exposure. This can be either a Balfour or a Bookwalter retractor.

Third Step—Exposure of the Appendix

After the peritoneum is entered, the cecum is identified. Sponge sticks can be helpful to sweep the small bowel in a lateral to medial direction in order to expose the cecum.

FIG 1 • Incision placement. A Rocky Davis (transverse) or McBurney (oblique) incision is used. The midpoint of the incision should be centered over the maximal point of tenderness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access