7 Anxiety and panic states

the CALM model

INTRODUCTION

It is impossible to live even an ordinary life without experiencing some form of stress. Major life events such as loss of a loved one, have been claimed to significantly affect health and well-being (Freeman 2001). Holmes and Rahe (1967) have categorized life events on the basis of the amount of life adjustment needed. Other authors have advocated that more commonplace stresses such as examinations, family arguments, transport difficulties and unexpected bills have a much larger summative impact on psychological states, outlook and well-being (Lazarus & Folkman 1989). Coe (1999) has identified different models, which attempt to explain the relationship between stress, immunity and disease:

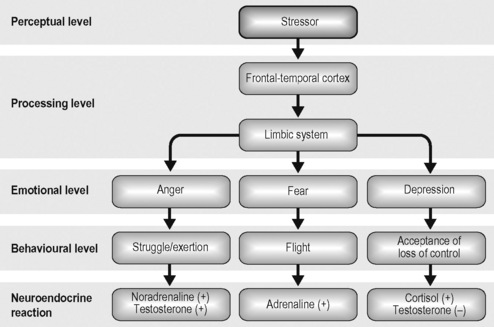

It is important for the therapist to have an understanding of the processes that are there to protect an individual physically (e.g. to run away from an imminent threat). In terms of responding physically to stress, the most direct brain pathway is the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) axis. This pathway functions by activating the ANS. It does this by using informational substances, neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, which communicate directly with the immune system triggering changes at tissue and cellular level. The second and less direct brain pathway is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This pathway triggers the endocrine system to release hormones as informational substances. These in turn modulate both physiology and immunity. Henry (1986) attempted to define three types of physiological reactions linked to an emotional experience to articulate how they influence behaviour (Fig. 7.1).

The connections between the emotional state, disease processes and experience have been, and continue to be, explored in the emerging science of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI). This is the seminal work of Ader and Cohen (1975) and Ader (1982). This theory centres on a 2-way relationship between the immune system and the central nervous system (Rabin et al 1989, Lloyd 1990). Chemical as well as hormonal changes play a key part in the process of responding to stress. Aside from adrenaline and noradrenaline, cortisol is also produced. This steroid is necessary for raising glucose levels, and has anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory properties, needed in fight-or-flight situations. However, chronically elevated cortisol is associated with an increased risk of depression, diabetes and cancer (Sterling & Eyer 1992). It is inevitable that many patients living with these conditions will have frequent and sometimes lengthy contact with health professionals and services. Importantly for this chapter, these patients will be subject to numerous medical investigations, procedures and treatments.

Even in healthy individuals, researchers have identified immunological effects of stress. Medical students have reported more illness associated with examinations than at any other time during their training (Glaser et al 1987). Participants were found to show reductions in natural killer cells, thought to be integral in defence against viral infections and neoplastic growth, during examination periods (Kiecolt-Glaser 1984).

As therapists, our work is important not only for helping with acute stressors, but also assisting patients, and sometimes their carers, to manage chronic stress. There have been numerous studies that have examined psychoneuroimmunological outcomes of therapeutic interventions such as behavioural therapy, guided imagery, massage and progressive muscle relaxation (Groer & Ohnesorge 1993, Groer et al 1994, McCain et al 1994) (see Ch. 6). It can be concluded that interventions to affect emotional states can influence physiological states, which in turn can have immunological effects.

In this chapter we will overview various stress-related concepts and explore hypnotherapy and other strategies in acute situations, not only to assist the patients to master their stress, but also to learn techniques that can help in the longer term. Critics of hypnotherapy and other complementary therapies have labelled reported positive outcomes as being merely a demonstration of the placebo effect. We would argue that it is vital to see ‘placebo’ as a valuable therapeutic effect rather than an unimportant artefact to be quickly dismissed. Indeed, Benson (1996) has suggested that the act of physically taking or receiving even a ‘placebo’ intervention can trigger ‘remembered wellness’. This process involves harnessing the patient’s belief system, giving them the confidence to access a memory of being in good health or a time without symptoms. Benson believes that techniques that promote relaxation can be a good opportunity to access this innate resource since it provides a time to quieten the mind and assist the body in its own healing.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

PANIC

Panic is an extreme form of anxiety with marked ANS arousal (Box 7.1) leading to a need to remove oneself from the situation, i.e. ‘run away’. Ignoring emerging feelings of panic does not help overcome it. The reactions are there to trigger the person to avoid harm. It is advisable to teach the patient to recognize his/her own panic responses and implement an intervention(s) suitable for him/her. It is important to acknowledge that the body cannot maintain a permanent state of panic.

PHOBIA

This term is often used too glibly, with <4% of the population at risk from phobic reactions. Phobias have been classically defined by Choy et al (2007: 267) as ‘characterized by an excessive, irrational fear of a specific object or situation, which is avoided at all cost or endured with great distress’. In terms of medical procedures, such as cannulation, it would be expected that the patient would quickly progress from a panic state to hyperventilating that would ultimately lead to a vasovagal reaction (Deacon & Abramowitz 2006).

WORKING WITH ANXIETY, PANIC AND PHOBIA STATES

It is very important to acknowledge that medical procedures can be extremely frightening for patients and their carers. Being cannulated repeatedly for blood sampling and/or for the administration of chemotherapy, particularly if unsuccessful can begin to become a feared event. Having your face covered in plaster or being clamped into position for radiotherapy (Fig. 7.2), even for short periods of time, can feel like being trapped. At the heart of the issue is feeling helpless and for some patients being reminded of previous episodes in their life when under threat or even being physically abused or raped.

A key to working with anxiety states is the construct of locus of control, first described by Rotter (1975). This has been measured using three subscales: external and internal loci of control and fatalism. Scores that are high on external locus are interpreted as the individual believing they have no or little control over their situation. Individuals scoring high on the internal locus of control subscale are described as having a sense of control and self-determination. It is important for therapists to recognize that individuals differ on how they personally control life situations, although certain psychosocial reactions, such as depression and anxiety are commonly reported among people living with life-threatening illness (Arias Bal et al 1991, Livneh & Antonak 1997). Interventions that can help to mitigate or alleviate acute stress can therefore be pivotal in assisting patients to maximize well-being, despite living with chronic and enduring illness. The interventions can also break the chains that lead some patients to develop anticipatory anxiety, panic states and phobic reactions. There are a number of possible co-factors that have been identified as contributing to this chain of events (Box 7.2). It is important for therapists/health professionals to be aware of these and assess patients exhibiting anxiety for risk.

Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) theoretical formulation differentiates between problem-focussed coping (i.e. strategies to alter stressful situations) and emotion-focussed coping (i.e. strategies to regulate feelings). For therapists and health professionals, there is a need to address both the problem and the reaction. For example, the problem might be venous access. Fear and anxiety will exacerbate this situation, with patients expressing the desire to escape and even withdraw from treatment as an ‘in the moment’ reaction. Sedating a patient may address the problem of the procedure, but not the feeling. In a study by Buelow (1991) investigating coping strategies, participant’s depressions and feelings of uncertainty about the future, lead them to express preference for emotion-focussed strategies. Ignoring the emotional needs by using sedation alone, we are not meeting the whole person in their distress. The cycle repeats itself with every stressful procedure, so reinforcing the inability of the patient to have any measure of control.

There are a number of risks and concerns when working with patients experiencing anxiety, panic and phobia states (Box 7.3). Aside from risks to the patient there are also repercussions for carers who can feel overwhelmed by seeing loved ones in so much distress. For staff repeatedly seeing acutely ill patients and their carers anxious and frightened contributes to ‘burnout’ (Iskihan et al 2004). Lacovides et al (2000) suggest that practitioners working in stressful clinical areas can acquire higher anxiety levels, performance disorders, and even symptomatology. Ethically, as well as economically, sedation presents problems, with a sedated patient less able to consent and needing greater recovery time, often requiring admission to hospital.