Antiepileptics

David E. Zimmerman

Outline

•Introduction

•Phenytoin

•Valproic Acid

•Phenobarbital

•Carbamazepine

•Levetiracetam

•Lacosamide

•Conclusion

•Sample Calculation: Phenytoin for Loading Dose

•Summary Table: Antiepileptic Agents

Antiepileptic medications like phenobarbital and phenytoin have been used for decades while a plethora of new agents have come to the market in the past 20 years. Some antiepileptic medications have a narrow therapeutic index or nonlinear pharmacokinetics (PK) that require therapeutic drug monitoring. Phenytoin and valproic acid (VPA), for example, exhibit nonlinear PK that can make dosing challenging. Some antiepileptic agents are metabolized, inhibited, or induce the cytochrome (CYP) P450 isoenzymes, leaving the potential for drug interactions to occur. The International League Against Epilepsy released a special report regarding requirements for therapeutic monitoring. Unfortunately, no guidance was given to the use of these antiepileptic medications in obese patients.1 This chapter will focus on the current knowledge that exists for dosing phenytoin, VPA, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, levetiracetam, and lacosamide in obese patients.

Phenytoin

Phenytoin is used for partial and generalized seizures and is one of the first-line therapies for status epilepticus.2 It demonstrates nonlinear (Michaelis-Menten) PK and is ~90% protein bound, mainly to albumin. Hypoalbuminemia and uremia can cause an altered free fraction, leading to possible toxicity if the dose is not corrected. Some institutions have free phenytoin levels to aid in assessing patients with these factors.2 The normal therapeutic range of total phenytoin is defined as 10 to 20 mg/L.

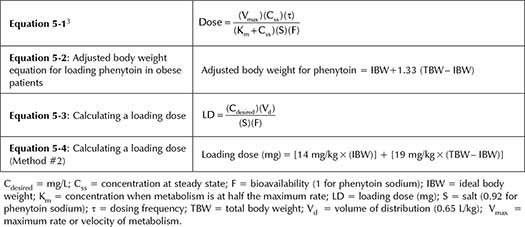

Equation 5-1, Table 5-1 shows the maintenance dosing equation based on the Ludden method.3 There are several PK parameters that need to be understood specifically when managing phenytoin. These include Vmax, which is the maximum rate or velocity of metabolism, and Km, which is the concentration at which metabolism is occurring at half the maximum rate.3 Normal population estimates for adults is a Vmax of 7 mg/kg/day and Km of 4.3 mg/L (some texts recommend using 5.8 mg/L for geriatrics >59 years old).3 Please note these are population parameters and can vary greatly among individual patients. It is also important to remember which formulation of phenytoin you are using as there are two salt (S) forms that exist. The intravenous (IV) and extended-release formulation of phenytoin contains sodium, and they have an S correction factor of 0.92. The chewable tablets and oral suspension are formulated as just phenytoin and have an S = 1. The population estimate for the volume of distribution (Vd) is 0.65 L/kg. (See Table 5-1.)

Special Note: Fosphenytoin is a prodrug of phenytoin and will be combined into the below discussion.

Table 5-1. Phenytoin Equations

Calculating a Loading Dose

The best evidence for calculating a loading dose of phenytoin in obese subjects comes from a study by Abernethy and Greenblatt.4 They investigated the PK effects of a single IV dose of 300 mg phenytoin over 10 minutes in 14 obese individuals (mean weight of 124 kg) and 10 control patients (mean weight of 67 kg). When adjusted based on percentage of ideal body weight (IBW), they found that phenytoin distributed greater into adipose tissue by a factor of 1.33, and thus a correction should be used (Equation 5-2, Table 5-1). To explain this, recall that clearance (Cl) = k × Vd, where k is an elimination rate constant and inversely proportional to half-life (t½). It may be easier to think of the equation as Cl = Vd/t½. In the above study, there was not a statistical difference in total mean Cl. There was, however, a significant increase in mean elimination half-life with 19.9 versus 12 hours in the obese and control groups, respectively (p <0.025). Because the half-life was increased but Cl was not changed significantly, Vd must then have been affected. This was the case as the total Vd was greater in the obese group compared to the control group (82.2 versus 40.2 L, respectively; p <0.001). Thus, an adjusted body weight is used for the dosing weight (Equation 5-2, Table 5-1) for patients who are >125% of their IBW. Equation 5-3, Table 5-1 can then be used to determine a specific dose based on a desired concentration. An additional and somewhat simpler method is to use Equation 5-4, Table 5-1, which is based on the traditional loading dose of 14 mg/kg but adjusts for the additional distribution.4 No specific dosage cap is recommended when calculating a loading dose. Therefore, clinical judgment should always be used, and remember that subsequent smaller doses can always be given if needed. (See Table 5-1.)

Maintenance Dosing

The prescribing information for phenytoin recommends an initial oral daily dose of 300 mg and then adjust per level.2 Pharmacokinetic texts will recommend two options to calculate a maintenance regimen in the general population: an empiric 5 to 7 mg/kg/day or by using Equation 5-1, Table 5-1 and include population parameters. It is unclear if a conventional dose of 300 mg/day will lead to subtherapeutic levels in obese patients. It is also important to remember that maintenance dosing relies on overall Cl.

Although investigating the effects of several parameters in a large group of adults on 300 mg/day of phenytoin, Houghton showed a minimal negative correlation (R2 = 0.08 for men and 0.13 for women) of weight on serum phenytoin levels (as weight increased, serum levels decreased).5 The poor correlation suggests other parameters—such as hepatic function, drug interactions, genetics, albumin, or other factors that were not included—may influence the PK model. A limitation of the study is that the authors evaluated all adults regardless of weight status. Kuranari and colleagues reported a case of a 19-year-old patient with a body weight of 93 kg (BMI 36.3 kg/m2) with normal renal and hepatic function and maintained on phenobarbital, phenytoin, VPA, and carbamazepine.6 Although there are interactions among these agents, the doses were kept the same throughout, serving as a potential control for this confounder. Over a 46-day period, the patient had a 7.5% weight reduction (7 kg) from baseline with no dose changes in the antiepileptic medications. Levels were taken at five different times during this period. VPA and phenytoin levels were closely associated with a change in Cl with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.62 and 0.64, respectively. This is based on the assumption that a decrease in weight (predominantly excess adipose tissue), and by connection Vd, were responsible for the decrease in Cl. If true, this would indicate that total body weight (TBW) would be a better predictor for Cl of phenytoin and VPA. Interestingly, carbamazepine and phenobarbital’s levels and Cl were not affected by a decrease in weight.

Lastly, there have been case reports of obese patients maintained on high doses of phenytoin. A male patient weighing 173 kg with a BMI of 54.5 kg/m2 was maintained on monotherapy of oral phenytoin 1,000 mg daily.7 The patient had serum phenytoin drug levels of 11.5 mcg/mL and 11.3 mcg/mL 6 months later. A second male patient weighing 135.5 kg, with a BMI of 41.6 kg/m2, was on a similar daily maintenance dose of 1,000 mg orally while on concurrent phenobarbital. In both of these cases, doses were increased over time and based on drug levels. Because of contradictory evidence (Level II and III evidence in nonobese individuals) that obesity has any effect on Cl (i.e., maintenance dosing), clinicians should use IBW.

Helpful Tips

•Phenytoin demonstrates nonlinear PK. As a result, small changes in doses can result in large increases in phenytoin levels.

•More frequent monitoring may be necessary for obese patients.

•If you are concerned that your IV loading dose was not enough, wait until at least 2 hours after the infusion is completed to draw a level.

•Make sure to assess for hypoalbuminemia as it can increase the free fraction.

•Phenytoin can induce, act as a substrate, and alter protein binding of many medications. Always evaluate drug interactions when initiating or discontinuing therapy.

Summary

•Loading dose (patient not previously on phenytoin/fosphenytoin): Adjusted dosing body weight using Method #1 (Equations 5-2 and 5-3, Table 5-1) or Method #2 (Equation 5-4, Table 5-1).

•For maintenance dosing: Either use IBW in weight-based regimens (Equation 5-1, Table 5-1) or conventional dosing of 300 mg/day should be used. Provide therapeutic drug monitoring of phenytoin levels and assess for efficacy and adverse events.

Valproic Acid

VPA is one of several options to be used as a first-line antiepileptic for generalized and partial seizures. VPA is also used as a mood stabilizer and for migraine prophylaxis. In patients with normal body weight, the Vd is estimated to be 0.12 to 0.16 L/kg; thus, it is a rather hydrophilic drug.8 The half-life of VPA is approximately 12 to 15 hours in normal body weight adults. A total therapeutic concentration is defined as 50 to 100 mg/L, although levels up to 120 mg/L have been recommended for mood stabilization.1,8 VPA is approximately 90% to 95% protein bound to albumin; and it follows nonlinear PK similar to phenytoin.8 At higher concentrations, protein binding becomes saturated and can lead to a higher free concentration (i.e., free fraction). Additionally, a higher free fraction has been seen in hospitalized patients, possibly due to a change in albumin.9

Dosing Weight

One would assume, due to the hydrophilic nature of VPA, that IBW would be a better predictor. But as discussed previously in the phenytoin section above, Kuranari and colleagues demonstrated that a decrease in weight led to a decrease in VPA Cl, leading one to think that TBW would be a better predictor of Cl.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree