36 Antidepressants

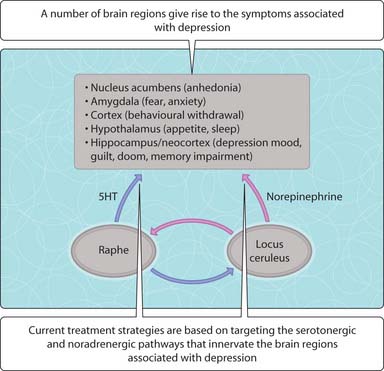

Clinical manifestation of depression is one of misery, a loss of enjoyment or participation in activities, sleep disturbances, loss of appetite and anxiety. The patient is pessimistic, lacks, self confidence, feels hopelessness, and may have suicidal tendencies. The intensity of these symptoms is increased in severe depression and the patient may suffer from hallucinations or become delusional. In less severe depression, the symptoms may be of a lesser intensity and are best described as neurotic (e.g. obsessional symptoms). In mania, subjects may exhibit hyperexcitable states, the seeming opposite of depression. Hence, affective disorders may be classified as either unipolar (mania or depression) or bipolar (both). The historical observation that patients treated with reserpine, which depletes sympathetic neurons of norepinephrine stores, suffered induced depression while patients treated with the antituberculosis drug isoniazid (shown to inhibit monoamine oxidase (MAO)) experienced relieved depression formed the rationale for developing drugs that elevate biogenic amines (serotonin, norepinephrine) within the CNS to treat depression. A complex interaction between several brain regions, serotonergic and noradrenergic nerves is implicated in depression (Fig. 3.36.1). Clinical benefits take weeks to manifest for a range of antidepressants indicating that a resetting of the activity of these neural circuits is required, rather than simply elevating neurotransmitter levels at synapses.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

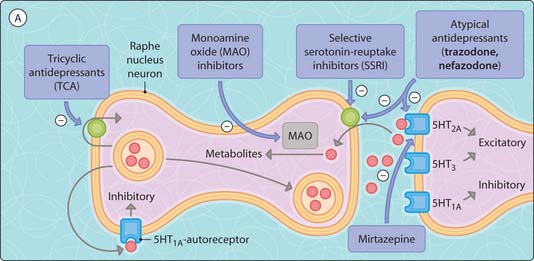

MAO metabolizes the biogenic amines and occurs in two isoforms, both metabolizing dopamine. MAOA metabolizes serotonin and norepinephrine outside storage vesicles, thus increasing the building blocks for new neurotransmitter synthesis into synaptic vesicles (Fig. 3.36.2). MAOB is selective for phenylethylamine.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree