Anticoagulants and Antiplatelets

Stacy Elder

Outline

• Anticoagulants

• Antiplatelets

• Summary Table: Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Dosing in Obesity

Anticoagulants serve as important therapeutic agents for a variety of disease states including prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE), primary and secondary prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, and secondary prevention following an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Like many agents, most of the anticoagulants were originally studied in populations that included a minimal number of obese patients. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) published the 9th edition of the Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines in 2012, with only one recommendation for specific alteration to drug dosing in obesity.1 Nonetheless, due to a variety of physiologic procoagulant and atherothrombotic effects induced by obesity, it is a risk factor for ACS, stroke, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, as well as VTE, thus prompting an increasing number of publications on dosing of anticoagulants in obese patients.2-6

The dosing strategies for anticoagulants often depend on indication, but both standard and weight-based dosing strategies necessitate additional considerations for obese patients.7 Absorption, distribution, and metabolism of anticoagulants may be altered by obesity.7 Standard dosing regimens, studied in primarily nonobese populations, present a concern as they may undertreat obese patients. However, weight-based dosing regimens studied in a primarily nonobese population present an equal concern with high total body weight (TBW) drug doses leading to the potential for excessive anticoagulation in obese patients. Thus, this section will aim to discuss the literature available for anticoagulant dosing strategies for VTE prophylaxis, therapeutic anticoagulation, and ACS secondary prevention in obese patients.

Unfractionated Heparin

VTE Prophylaxis Dosing

Several studies have shown that VTE events are more common in obese patients.6,8,9 Perhaps most compelling is the large-scale study utilizing the National Hospital Discharge Survey, which reported that among obese hospitalized patients, 0.76% were diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism (PE) and 2.02% were diagnosed with a deep venous thromboembolism (DVT).6 In comparison, 0.34% of nonobese hospitalized patients were diagnosed with a PE (RR 2.50, 95% CI 2.49 to 2.51), and 0.8% were diagnosed with a DVT (RR 2.21, 95% CI 2.20 to 2.31).6 Obese patients also were found to have a higher recurrence rate of VTE than nonobese patients.9 Among obese patients, bariatric surgery presents a uniquely high-risk population of surgical inpatients, and the rise in data supporting bariatric surgery outcomes has spurred recent publication of numerous dosing studies for VTE prophylaxis, primarily low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), in this population.

Although unfractionated heparin (UFH) has been largely replaced by LMWH or oral anticoagulants in many disease states, it is still used frequently for VTE prophylaxis.10 The standard dose of UFH for VTE prophylaxis is a fixed dose of 5,000 units two to three times daily administered subcutaneously.1,11 However, it is common practice to prescribe higher doses of heparin for prophylaxis in patients weighing >100 kg or body mass index (BMI) ≥40 kg/m2. Although this is not strongly supported by literature, there is one retrospective study in a general population of Obese Class III (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) inpatients that specifically addresses high-dose thromboprophylaxis, defined as either UFH 7,500 units subcutaneously three times daily or enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously twice daily.12 The institution implemented standard order sets that recommended these high-dose prophylactic regimens in patients who weighed >100 kg and had a BMI ≥40 kg/m2.12 Of the patients who met these criteria and received high-dose prophylaxis, 0.77% developed a VTE inpatient, compared to 1.48% of those who received standard dose prophylaxis (or 0.52, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.00).12 No increase in bleeding was noted in the high-dose prophylaxis group; however, only 42.1% of patients recommended for high-dose prophylaxis were ordered one of these regimens by the prescriber.12 Noncompliance with suggested dosing of VTE prophylaxis in obese patients was noted in another study, and it is hypothesized to occur secondary to ambiguity regarding optimal dosing in this population.13

Bariatric Surgery UFH Dosing VTE Prophylaxis—In addition to controversy over ideal dosing of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in obese patients, it has been hypothesized that excess adipose tissue may influence absorption of subcutaneous UFH injections.10,14 As an alternative to subcutaneous UFH administration in bariatric surgery patients, several research groups studied the efficacy and safety of continuous intravenous (IV) UFH as VTE prophylaxis.15,16 These small-scale studies demonstrated low or no VTE events and few bleeding complications but significantly increased administration complexity to run a continuous infusion, sometimes requiring an extra admission day and consistent monitoring.15,16 More recently, a direct comparison of UFH to LMWH was conducted, showing overall superiority of utilizing LMWH either before and after bariatric surgery, or following bariatric surgery with UFH utilized prior to the surgery.17 The data, along with increasing data on optimal dosing of LMWH (see section on LMWH), have led to a majority of patients receiving LMWH as perioperative VTE prophylaxis for bariatric surgery.

Therapeutic UFH Dosing

Decreasing the initial time to therapeutic IV UFH dosing is associated with decreased recurrence of VTE.18,19 In nonobese patients, a study by Raschke and colleagues showed that a weight-based dosing regimen is more likely to achieve therapeutic activated prothrombin times (aPTTs) at 24 hours than a standard regimen, demonstrating a correlation between weight and UFH requirements.18 Heparin has a volume of distribution (Vd) similar to blood volume. Obese patients have additional adipose tissue compared to nonobese patients, which requires additional blood supply but significantly less blood volume than required for lean tissues.20

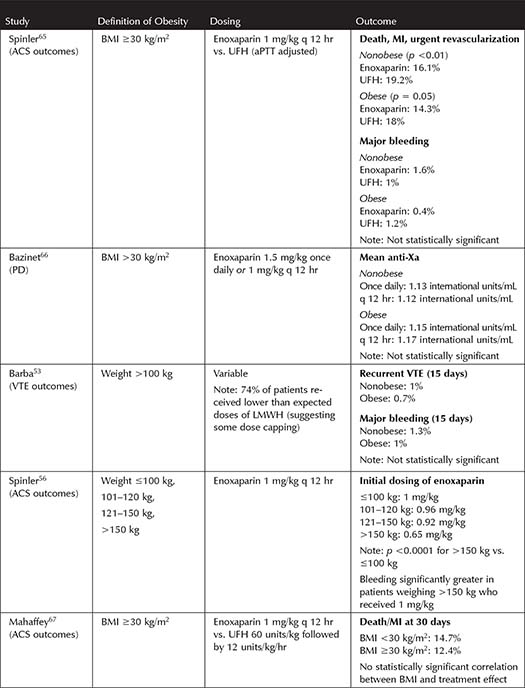

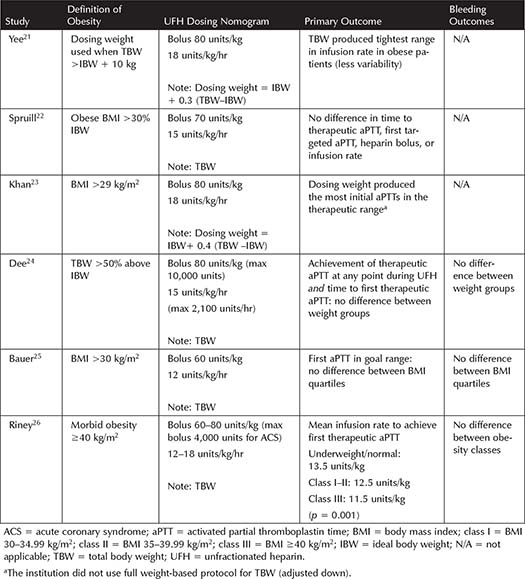

Several trials, with varying definitions of obesity, have been published suggesting that modified dosing regimens may be necessary to rapidly achieve a therapeutic aPTT on UFH, without risking excessive anticoagulation (see Table 3-1). Overall, utilizing TBW for dosing therapeutic UFH was not found to cause more bleeding, but in practice the infusion rate is often capped or decreased in obese patients.21-26 This practice is not unreasonable given that studies have shown a potential increase in supratherapeutic aPTT, decreased UFH requirements to achieve therapeutic aPTT with increasing BMI, and no consistent benefit of giving uncapped, full dose UFH based on TBW.22-26

Helpful Tips

•Absorption of subcutaneous UFH is likely decreased in patients with excess adipose tissue.

•When deciding on a dose of UFH for prophylaxis, consider the indication, weight, and BMI.

Summary

•Although it is a common practice, minimal literature exists to support increased dosing of UFH for VTE prophylaxis in obese patients.

•One study found improved rates of VTE without increased bleeding in patients who weighed >100 kg and had a BMI ≥40 kg/m2 who received either enoxaparin 40 units subcutaneously twice daily or UFH 7,500 units subcutaneously three times daily for VTE prophylaxis.

•Data suggest that continuous UFH infusion resulted in low or no VTE events and few bleeding complications but significantly increased administration complexity; therefore, VTE prophylaxis for bariatric surgery has largely been replaced by LMWH.

•It is reasonable to utilize TBW for dosing and to apply an adjusted regimen (i.e., lower boluses and infusion doses in units/kg) or dose capping for initial anticoagulation strategies for therapeutic UFH.

Low Molecular Weight Heparin

VTE Prophylaxis Dosing

Although VTE prophylaxis with UFH or LMWH has historically been a fixed dose for all patients, a growing body of literature suggests that VTE prophylaxis in obese patients should be weight-based.27-46 Most literature supporting weight-based dosing of LMWH for VTE prophylaxis has targeted outcomes of achieving a goal anti-Xa level. The optimal anti-Xa level for decreasing VTE events has not been clearly supported by robust literature and is primarily based on expert opinion.27,28 Anti-Xa is typically measured as a peak (4 to 6 hours after the dose), but more recent literature suggests that low trough anti-Xa levels (<0.1 international units/mL) were associated with increased VTE, leading to more confusion about optimal targets and use of anti-Xa levels.40 In the absence of strong supporting literature, anti-Xa levels of 0.2 to 0.5 international units/mL are typically considered the goal for VTE prophylaxis. Dosing of enoxaparin for VTE prophylaxis in obese patients has been published primarily in three patient populations: medical, surgical/trauma, and bariatric surgery.

Table 3-1. Studies Incorporating Unfractionated Heparin Dosing in Obesity

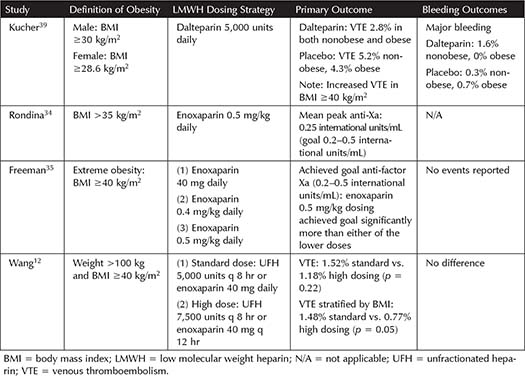

Medical Patients—Although obese medical patients may not have the same degree of risk factors as obese surgery or trauma patients, they are still at increased risk of VTE compared to nonobese patients.1-3,5,6 Most studies have sought to optimize dosing to target a goal anti-Xa level and have shown that a variety of increased, weight-based dosing strategies are more successful than standard dosing (see Table 3-2). Pharmacodynamic (PD) studies suggest that enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg daily achieves target anti-Xa levels more often than fixed dose or lower doses of enoxaparin in medical patients.34,35 Wang and colleagues published one of the most robust trials to assess clinical outcomes for pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis dosing in obese patients.12 The study implemented increased doses of either UFH or enoxaparin but showed a nearly 50% decrease in VTE when administered to patients weighing >100 kg with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2.12 Based on these PD and clinical outcomes trials, it is reasonable to consider an increase in dose of VTE prophylaxis for obese medical inpatients.

Table 3-2. Studies Incorporating Low Molecular Weight Heparin Dosing for Prophylaxis in Obese Medicine Patients

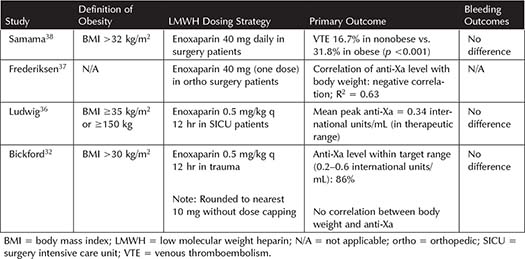

Nonbariatric Surgery/Trauma Patients—Surgical and trauma patients are at an increased risk of VTE.27,28 Often this patient population requires higher doses of enoxaparin to achieve anti-Xa levels >0.2 international units/mL, which is thought to be due to a variety of factors including hypermetabolic state and peripheral edema resulting in decreased subcutaneous drug absorption.41,42 Table 3-3 summarizes the PD and clinical outcome studies for LMWH dosing in obese trauma and nonbariatric surgery patients. PD studies confirm the need for increased doses of enoxaparin to achieve target anti-Xa levels reliably in obese surgery and trauma patients.32,36,37 Enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg every 12 hours was found to attain higher anti-Xa levels and maintain the target range compared to lower doses.32,36,37 Although no differences in bleeding were noted, the numbers of patients enrolled in these studies were small; thus, they were not powered to assess this outcome.32,36,37 The only trial assessing a clinical outcome in nonbariatric surgery patients indicated that enoxaparin 40 mg daily was not adequate in those with a BMI >32 kg/m2, as the rate of VTE was nearly doubled in the obese population compared to the nonobese.38 Currently available data indicate that increased dosing of enoxaparin may be reasonable for VTE prophylaxis in obese trauma and surgery patients, but no data exist on specific strategies for optimizing dosing of LMWH in this population.

Table 3-3. Studies Incorporating LMWH Dosing for Prophylaxis in Obese Nonbariatric Surgery and Trauma Patients

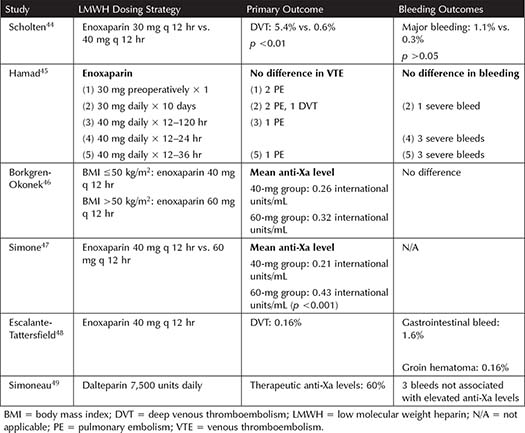

Bariatric Surgery Patients—When compared to UFH, LMWH was found to be superior for prevention of VTE in bariatric surgery patients, with no difference in bleeding outcomes.17 Table 3-4 summarizes the literature from several studies for LMWH in bariatric surgery patients. A study by Scholten and colleagues found that enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily decreased DVT in comparison to 30 mg twice daily, with no major difference in bleeding.44 Several studies have evaluated average anti-Xa levels achieved with varying doses of enoxaparin. A study of enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily compared to 60 mg twice daily achieved average anti-Xa levels of 0.21 international units/mL compared to 0.43 international units/mL, suggesting that enoxaparin 60 mg may be more likely to achieve anti-Xa targets for prophylaxis.47 A separate study assessed these same doses, but specifying the dose for patients with a BMI <50 kg/m2 (enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily) or ≥50 kg/m2 (enoxaparin 60 mg twice daily).46 Interestingly, in the patients with a higher BMI, receiving more enoxaparin, the mean anti-Xa was not significantly different than the patients in the lower BMI group receiving the lower dose of enoxaparin.46 One study utilizing an increased dose of dalteparin (7,500 units daily) found that only 60% of patients achieved a therapeutic anti-Xa, and that increasing weight correlated with decreasing anti-Xa levels on this dose of dalteparin.49 A systematic review and meta-analysis, including some of these trials, did not find a difference between weight-based and standard dosing of LMWH (and UFH), as VTE rates among patients who received weight-based dosing (0.54%, 95% CI: 0.2% to 1%) were not significantly less than standard dosing (2%, 95% CI: 0.1% to 6.4%).43

Table 3-4. Studies Incorporating Low Molecular Weight Heparin Dosing for Prophylaxis in Bariatric Surgery Patients

Summary

•Together, these studies assessing PD and clinical outcomes suggest that the standard fixed dosing of LMWH may not provide optimal VTE prophylaxis in obese patients.

•Medical Patients—Enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously every 12 hours should be considered if a patient weighs >100 kg and has a BMI ≥40 kg/m2.12 Alternatively, 0.5 mg/kg daily can be considered for patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2; however, this dose was found only to improve achievement of therapeutic anti-Xa levels and has not been proven to impact clinical outcomes.34,35

•Nonbariatric Surgery/Trauma Patients—Enoxaparin 40 mg daily is not sufficient for VTE prophylaxis. Enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg twice daily may be a reasonable dose, but data suggesting the efficacy of this dose are based on achievement of therapeutic anti-Xa levels and further studies to determine clinical impact.

•Bariatric Surgery Patients—LMWH is the preferred medication for VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery; however, many increased dosing strategies have been employed and found variable effects on anti-Xa and clinical outcomes.

Therapeutic LMWH Dosing

Therapeutic dosing of LMWH is weight based, and studies have historically not included dose capping for obese patients. LMWHs are fully absorbed from subcutaneous tissue, albeit more slowly with increased adipose tissue, and primarily distributed in the intravascular space.50,51 These properties have led some to hypothesize that dose capping or reduced dosing for obese patients may be appropriate, given decreased vascularization of adipose tissue as compared to lean tissue.52, In practice, lower-than-standard dosing has been utilized in obese patients, given a fear of overanticoagulation with standard dosing based on TBW.52-56 The need for studies to clarify the benefits and risks of dose reduction or capping in obese patients has driven several publications that have attempted to further elucidate optimal LMWH dosing.

In addition to questions regarding dosing of LMWH in obese patients, there is ambiguity regarding utility of anti-Xa levels for monitoring the degree of anticoagulation. As with prophylactic LMWH, anti-Xa levels can be monitored, but a strongly validated therapeutic range for anti-Xa levels in any disease state is lacking.30 A review suggested target anti-Xa peak (4 hours after dose) range for twice daily dosing of enoxaparin for VTE is 0.6 to 1 international units/mL.30 For once-daily dosing in VTE, a target range of 1 to 2 international units/mL has been suggested.30 In ACS, a peak level of 0.5 to 1.2 international units/mL has been suggested based on prior editions of the ACCP guidelines; however, the authors of this review suggest that anti-Xa monitoring is not necessary for patients weighing up to 190 kg and potentially for larger patients.30 The most recent version of the guidelines no longer addresses monitoring anti-Xa levels in obese patients anticoagulated with LMWH for any indication.57

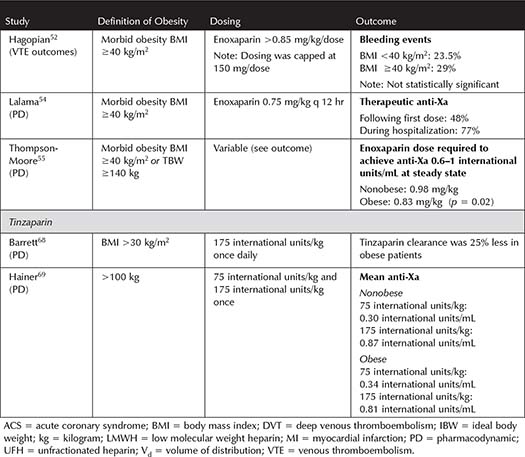

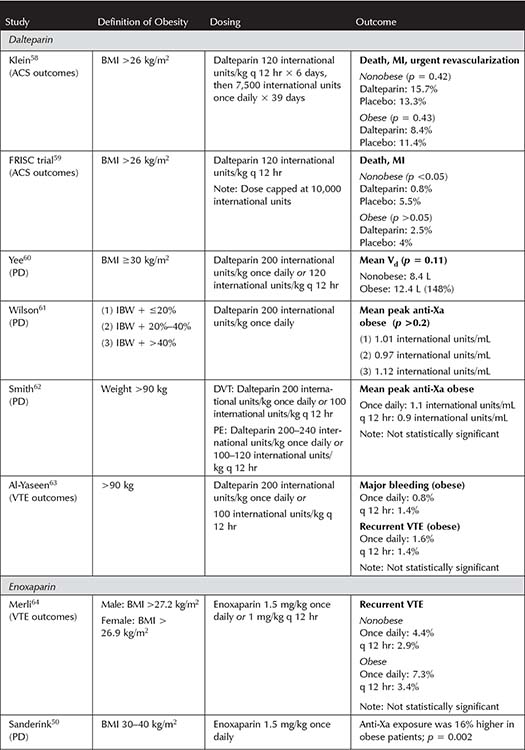

Therapeutic LMWH Dosing in VTE—In 2009, a review of literature on LMWH dosing in obesity and renal impairment summarized the data available for both prophylactic and therapeutic dosing, making evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice.30 Nutescu et al. recommended dosing LMWH based on TBW with no dose capping for VTE. They also suggested dalteparin and tinzaparin may be dosed once daily, but that enoxaparin may best be dosed twice daily based on a trend toward increased recurrence of VTE with once-daily dosing in one study.30 Since that time, a few new studies have added to the evolving body of literature on LMWH dosing in obese patients with VTE or ACS. Applicable studies to date can be reviewed in Table 3-5.50,52-56,58-69

For enoxaparin, two additional PD studies have been published since the 2009 review of LMWH dosing in obesity.54,55 Both studies describe the potential need for decreased doses of enoxaparin in this population. One study found that a reduced dose of enoxaparin (0.75 mg/kg every 12 hours) achieved therapeutic (0.6 to 1 international units/mL) anti-Xa levels in 48% of patients after the first dose, with 16% subtherapeutic after the first dose.54 The only dose adjustments needed were decreases secondary to supratherapeutic anti-Xa levels.54 The average dose of enoxaparin needed to achieve a therapeutic anti-Xa was 0.71 mg/kg, similar to another case series at the time, prompting the authors to conclude that dosing enoxaparin at 0.75 mg/kg every 12 hours without dose capping is appropriate in patients with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2.54,70 However, this study only included 31 patients and utilized anti-Xa as a surrogate endpoint for clinical outcomes.54 Similarly, a study published in early 2015 found that the dose of enoxaparin needed to achieve therapeutic steady-state anti-Xa levels (0.6 to 1 international units/mL) in patients with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2 or weighing >140 kg was 0.83 mg/kg every 12 hours.55 Receiving >0.95 mg/kg every 12 hours was associated with higher rates of supratherapeutic anti-Xa levels but no difference in subtherapeutic levels, bleeding, or recurrent thrombosis.55 Authors concluded that it would be reasonable to initiate enoxaparin therapy at a lower starting dose than 1 mg/kg every 12 hours and monitor anti-Xa levels.55 Notably, this study was not powered to detect differences in clinical outcomes, and no thrombotic events occurred in the follow-up period.55

Table 3-5. Studies Incorporating Therapeutic Low Molecular Weight Heparin Dosing for Venous Thromboembolism in Obesity

Hagopian et al. retrospectively analyzed rates of bleeding in morbidly obese patients, particularly those weighing >150 kg, receiving standard dosing of enoxaparin at their institution.52 The final analysis included 100 morbidly obese patients and 200 control group patients. The largest patient included in the study was 175.5 kg, but no patients received more than 150 mg enoxaparin/dose, and anti-Xa levels were not monitored regularly. Similar to the recent PD studies, the initial and final enoxaparin doses were significantly lower in the morbidly obese population.54,55 Bleeding events up to 24 hours after the last dose of enoxaparin were similar between the morbidly obese cases and the control patients (29% versus 23.5%, p = 0.30). The number of thromboembolic events was very low but not different between cases and controls.52 Further literature is needed to determine the efficacy of enoxaparin for prevention of thrombotic events when capped at 150 mg/dose, particularly in patients larger than 175 kg.

Summary

•Previous clinical practice recommendations suggest dosing all LMWHs using TBW for treatment of VTE.30 Since then, small studies targeting therapeutic anti-Xa levels for enoxaparin have indicated that reduced starting doses (<1 mg/kg every 12 hours or capped doses) would be better.52,54,55

•It is reasonable to dose LMWH based on TBW in obese patients, with consideration of dose reduction in patients at high risk of bleeding, if anti-Xa levels are monitored.

Therapeutic LMWH Dosing in ACS—In contrast to VTE, dose capping is standard for LMWH in ACS.30,71,72 In patients with ST-elevation ACS, enoxaparin should be dosed as a 30-mg IV bolus followed by 1 mg/kg every 12 hours, capped at 100 mg (or 0.75 mg/kg every 12 hours capped at 75 mg for patients >75 years old) for the first two doses.71 Dalteparin should be dosed 120 international units/kg every 12 hours based on TBW, capped at 10,000 international units for non-Q-wave ACS and unstable angina.72 Nutescu et al. confirmed the need for dose capping with LMWH in ACS in their 2009 review, and since then two analyses have been published on the implications of weight on treatment effects of enoxaparin.56,67 In a retrospective cohort study of patients from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines) database, authors sought to understand dosing of enoxaparin in practice and effects of BMI on bleeding risk with standard dosing.56 The median initial dose of enoxaparin significantly decreased in patients weighing >150 kg compared to those weighing <100 kg (0.65 mg/kg versus 1 mg/kg, p <0.0001).56 Of the patients weighing >150 kg, 80% received a dose reduction for the initial dose of enoxaparin.56 Interestingly, when patients weighing >150 kg received the recommended dose of enoxaparin (1 mg/kg), a significantly higher risk of bleeding was observed compared to those who received a lower dose (adjusted 2.42), potentially justifying the decrease in initial dose that was observed in clinical practice.56

Similarly, the SYNERGY (Superior Yield of the New Strategy of Enoxaparin, Revascularization, and Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors) database allowed for analysis of the relationship between BMI and enoxaparin dosing in a large, non-ST elevation ACS population.67 Increasing BMI was associated with better 1-year mortality up to 30 kg/m2, but higher BMI was no longer statistically significant for an association. Thirteen percent of obese patients received <1 mg/kg of enoxaparin, indicating dose capping or reduction during the study, although this was not part of the study protocol. There was no difference in 30-day death or MI, or bleeding in relation to BMI, indicating that there was no significant interaction between treatment effect with enoxaparin (or UFH, the comparator drug in the original study). Thus, this study concluded that obesity itself, with enoxaparin dosing reduced in some patients, was not a risk factor for worse bleeding or ischemic outcomes following non-ST elevation ACS, and in fact it may be associated with better outcomes.67

Helpful Tips

•When dosing LMWH, consider indication, weight, BMI, and renal function.

•Minimal evidence exists to support the clinical relevance of this outcome, and anti-Xa monitoring is not routinely suggested in obese patients.

Summary

•The prescribing information for enoxaparin and dalteparin contains maximum recommended doses in ACS.71,72

•Studies conducted in the setting of modern therapies (clopidogrel, common revascularization) indicate that dose capping is common practice and likely does not adversely affect ischemic or bleeding outcomes, and in fact it may improve these outcomes in ACS.

Subcutaneous Xa Inhibitor

Fondaparinux

Fondaparinux is a subcutaneous Xa inhibitor that is indicated for prevention and treatment of VTE. Similar to LMWHs, fondaparinux has a small Vd and primarily remains in the intravascular space.73 Fondaparinux is 100% bioavailable via the subcutaneous route, and the half-life is 14 to 20 hours, allowing for once-daily dosing for both treatment and prophylaxis.73 It is also structurally dissimilar to any of the heparin products, making it a therapeutic option for patients with a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

For VTE Prophylaxis—Although utilizing standard doses of fondaparinux in obese patients is a concern based on drug distribution and fear of inadequate achievement of concentrations, studies of VTE prophylaxis in orthopedic surgery patients also found that plasma clearance was increased by 9% for every 10-kg increase in weight.74 In a meta-analysis of four studies of fondaparinux compared to enoxaparin in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery, the effect of BMI on clinical outcomes with fondaparinux was not extensively studied.75 However, there was no difference in overall benefit of fondaparinux compared to enoxaparin when stratified by BMI greater than or less than 30 kg/m2.75 Although an overall increase in bleeding was noted with fondaparinux, no data are available regarding potential correlation with BMI.75

A retrospective study of morbidly obese (BMI >40 kg/m2) inpatients receiving fondaparinux 2.5 mg daily for VTE prophylaxis sought to determine what percentage achieved therapeutic anti-Xa levels (0.3 to 0.5 international units/mL) at steady state.76 Forty-five patients were included, with a mean weight of 142 kg and a mean BMI of 51.2 kg/m2. The average anti-Xa at steady state was 0.34 international unit/mL, and more anti-Xa values were subtherapeutic (47%) than supratherapeutic (11%) or within the therapeutic range (43%). Renal function, gender, BMI, and number of fondaparinux doses (before collection of anti-Xa sample) correlated with anti-Xa. No significant differences in VTE or bleeding were noted in this small population. Although this study concluded that the standard dose of fondaparinux often resulted in anti-Xa levels below goal, the correlation of anti-Xa levels and clinical outcomes is unclear; thus no recommendations can be made for dose adjustments in obesity at this time.76

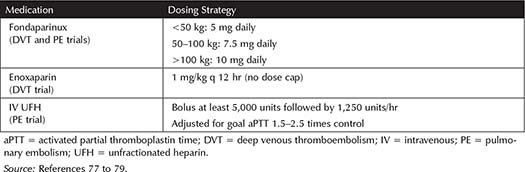

For VTE Treatment—The Matisse trials compared fondaparinux to enoxaparin for treatment of DVT and IV UFH for treatment of PE without weight restrictions.77,78 Fondaparinux was found to be noninferior to enoxaparin and UFH in the total population of the respective trials.77,78 An analysis of the obese patients in these studies sought to identify any effects of weight on outcomes.79 See Table 3-6 for dosing utilized for each medication in the Matisse studies.

Table 3-6. Matisse Trials Medication Dosing

Of the 4,418 patients in the Matisse trials, 496 weighed >100 kg, and 1,216 had a BMI >30 kg/m2.79 No differences were noted in rate of recurrent VTE at 3 months or major bleeding during the study period when comparing patients who weighed >100 kg to those weighing <100 kg. Similarly, when comparing patients with a BMI >30 kg/m2 to those with a BMI ≤30 kg/m2, there were no differences in VTE or major bleeding. The total dose of enoxaparin administered to patients in the study (in mg/kg) was not available for comparison. Regardless, noninferiority of fondaparinux when compared to enoxaparin or IV UFH for treatment of DVT or PE, respectively, was confirmed in all weight and BMI groups.79

Helpful Tips

•Fondaparinux is a potential anticoagulation option in patients with HIT.

•Renal function should be considered when dosing fondaparinux.

•Inpatients receiving standard dosing of fondaparinux (2.5 mg) for VTE prophylaxis often had anti-Xa levels below goal; however, more information is needed to determine the clinical utility of goal anti-Xa levels and any potential fondaparinux dose adjustments.

•For VTE treatment, weight-based dosing adjustments for fondaparinux (see Table 3-6) resulted in similar protection against recurrent VTE without increasing major bleeding in both obese and nonobese patients.

Intravenous Direct Thrombin Inhibitors

Bivalirudin

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree