Anorectal Disorders

Michael R.B. Keighley

Fissure in Ano

The principal clinical presentation of fissure in ano is intense anal pain during defecation, often associated with a small amount of bright red bleeding noticed on the toilet paper. There may be perianal swelling from a skin tag and discharge of mucus. There is often a sensation of tearing during defecation, and there may be a dull ache in the perineum 3 to 4 hours after bowel evacuation.

Women are more commonly affected than men, in a ratio of approximately 58% to 42%, respectively. Most patients are in the third decade of life, but fissure can occur at any age and is well recognized as a cause of pain and constipation in children. Fissure may be exacerbated by a recent episode of constipation and straining. It commonly occurs in women after vaginal delivery. It may occur as a complication of severe diarrhea.

Inspection of the perineum reveals a small, shallow anal ulcer with a sentinel pile and edema, usually in the posterior aspect of the anal margin, particularly in men. Fissures occur anteriorly in 40% of women.

Causes

The causes of fissure in ano are unknown. Primary fissure is often associated with alteration in bowel habit, particularly an episode of constipation. Postpartum fissure may be a result of tearing of the anterior aspect of the anal canal during childbirth. Local trauma is believed to be responsible for the initial skin defect that leads to a boat-shaped ulcer, resulting in chronic symptoms.

Primary fissure in ano may be acute. If healing does not occur, the fissure becomes chronic, in which case the ulcer enlarges in

size. There is edema around the fissure associated with an anal skin tag. In 10% of chronic fissures, there is a low intersphincteric anal fistula communicating between the base of the fissure and the dentate line.

size. There is edema around the fissure associated with an anal skin tag. In 10% of chronic fissures, there is a low intersphincteric anal fistula communicating between the base of the fissure and the dentate line.

Anal fissure is associated with increased resting anal canal pressures. Motility studies reveal ultraslow waves indicative of increased internal anal sphincter activity. Some data suggest that anal fissure is associated with a local reduction in blood flow. Healing of anal fissures is associated with a return to normal anal canal pressures with normal blood flow measurements.

Secondary fissure in ano may occur as a complication of Crohn’s disease, anal tuberculosis, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Occasionally, fissure in ano may complicate a previous operation on the anal canal. Fissures complicating Crohn’s disease and tuberculosis are often painless. By contrast, anal fissures and ulcers complicating AIDS are often intensely painful and are associated with incontinence and local sepsis.

Diagnosis of anal fissure can usually be achieved by inspection. Gentle parting of the buttocks reveals an edematous skin tag and a shallow anal ulcer, usually situated posteriorly in men but anteriorly in women. There is puckering of the perianal skin as a result of intense spasm of the anal sphincters. Digital examination is often impossible and should not be attempted in patients with severe pain, because the diagnosis can be made by inspection. In patients with chronic anal fissure, digital examination and proctoscopy are often well tolerated. The fissure has edematous margins and is boat shaped, with the transverse fibers of the internal anal sphincter seen at the base of the fissure.

Sigmoidoscopy should be performed in patients who can tolerate a rectal examination to exclude a primary cause for fissure in ano and any rectal pathology.

Nonspecific Medical Therapy

Up to 70% of chronic anal fissures will heal by conservative therapy alone. If patients have a history of chronic constipation, treatment should include a bulk laxative, such as methylcellulose or psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid, with a mild laxative, such as bisacodyl or docusate sodium. Patients should be told to avoid straining and be instructed in basic anal hygiene.

Application of local nonsteroidal preparations to control pain may be helpful. Local anesthetic agents may be effective, particularly for acute anal fissure. Steroid preparations may be used to reduce inflammation. A wide variety of commercially available ointments and suppositories exist, which consist of local anesthetic and steroid preparations. The cumulative relapse rate after these forms of medical treatment for chronic anal fissure is, 50% at 12 months.

Specific First-Line Therapy: Nitric Oxide Donors or Calcium Channel Blockade

No patient in the United Kingdom today is treated by sphincterotomy for anal fissure unless at least first line, and in some cases, second-line treatment is used because of the fear of bowel incontinence with sphincterotomy.

The most widely used first-line therapy is with nitric oxide donors, usually glyceryl trinitrate cream, but other formulations of topical nitrates give identical results. The cream is applied, where possible, over the fissure after defecation and at night initially, increasing the applications to four times a day if symptoms do not rapidly improve. The principle complication is headache, occurring in 30% to 40%, but if treatment can be tolerated, there is tachyphylaxis in most people such that the headaches do not persist for more than 5 to 6 days. Nitric oxide donors are not tolerated in 20% to 30% because of persistent headache. If patients are able to persist with therapy for 4 weeks, there is complete alleviation of anal pain in 60% to 70%, but in 10% to 20% there may be a relapse of the anal fissure during the next 3 months. Thus, healing is achieved in 45% to 60% of patients in 3 months. For those who relapse a repeat treatment course achieves healing in a further 20% to 30%, overall healing is 60% to 80%.

If patients have a persistent anal fissure and symptoms or cannot tolerate nitric oxide donors the alternative first-line therapy is the use of diltiazem, a calcium channel blocker. Diltiazem cream is used topically over the fissure twice daily initially but up to four applications a day if needed. The preparation is more expensive, but there are virtually no side effects. The outcome in terms of resolution of pain is comparable to those achieved with topical nitrates; pain free at 4 weeks 60% to 70%, with healing at 3 months of 40% to 60%. For those who relapse a repeat course achieves healing in 20% to 30%, overall healing is 60% to 80%.

Specific Second-Line Therapy: Botulinum Toxin

When first-line therapy fails, injection of Botulinum toxin into the intersphincteric plane away from the fissure, usually at 3 and 9 o’clock, with a dose varying from 2.5 to 20 units at each site achieves healing in 40% to 60%. Complications include transient incontinence, hematoma, or sepsis, but these are unusual. For refractory cases, repeat injection can be used. Since transient incontinence is now recognized, patients must be warned about this.

Surgical Principals

Patients with anal fissure can be treated surgically during an office visit or in an outpatient surgical unit, but an operation should not be advised until specific first- or second-line treatment has been vigorously pursued. The purpose of surgical treatment is to reduce excessive activity in the internal anal sphincter. In the past this was attempted by anal dilatation, but now only sphincterotomy is used and only after very thorough counseling about the risks of impaired continence.

Anal dilation results in disruption of the fibers of the internal and external anal sphincters. Unfortunately, anal dilatation is associated with a variable risk of bowel incontinence depending on risk factors, but incontinence to flatus is common and may be permanent. For this reason, anal dilatation is no longer advised for the treatment of anal fissure and will, therefore, not be described.

The alternative is internal anal sphincterotomy, which results in division of a part of the internal sphincter, but leaves the external sphincter intact. Sphincterotomy may be performed as a subcutaneous, blind technique or may be performed as an open operation. All patients having sphincterotomy must be warned that there is a risk of temporary or even permanent bowel incontinence following treatment. Preoperative bowel preparation with a disposable enema is usually advised. Postoperatively, the patient should be prescribed adequate analgesics and local anesthetic creams, as well as a mild laxative to avoid postoperative constipation. Patients should be warned that there is a 3% risk of postoperative bleeding, and that local pain may continue for 2 to 3 weeks. Flatus incontinence and soiling is usually transient, lasting only 2 to 3 months, but may occur in 20% to 40% of patients. Long-standing incontinence and soiling may complicate internal sphincterotomy and is not confined to patients in whom a part of the external sphincter has been

inadvertently divided. It can occur when the internal anal sphincter alone has been divided.

inadvertently divided. It can occur when the internal anal sphincter alone has been divided.

Closed Lateral Subcutaneous Internal Sphincterotomy

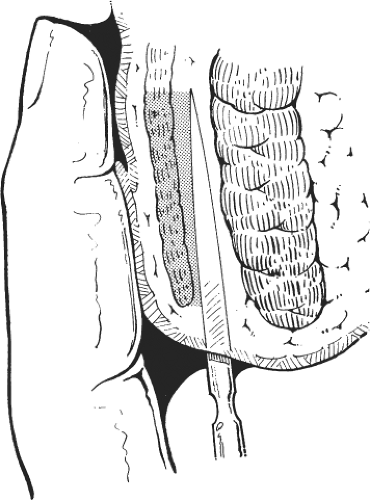

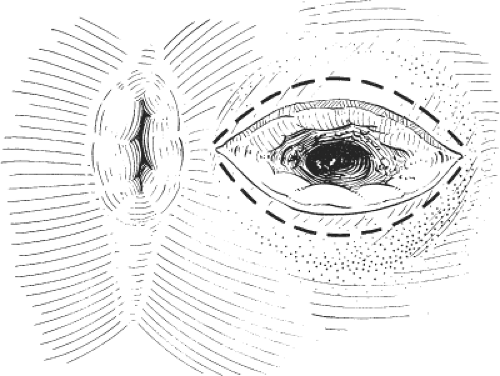

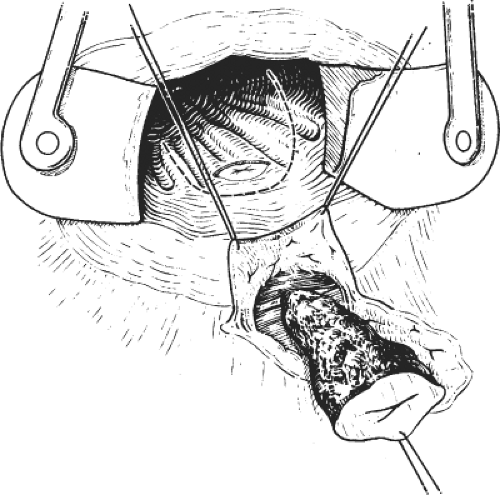

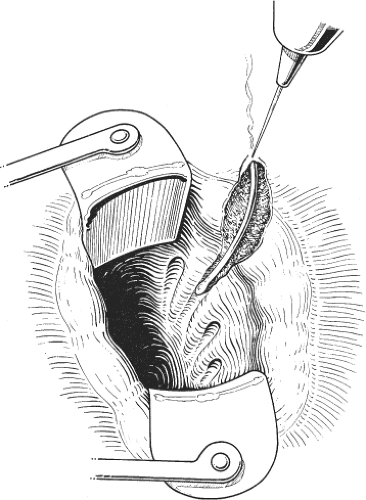

This procedure may be performed with local or general anesthesia. The intersphincteric groove is identified. Twenty milliliters of a local anesthetic with a weak adrenaline solution is infiltrated in the submucosal and the intersphincteric planes. A fine cataract blade is inserted in the intersphincteric groove with the blade lying parallel to the circular fibers of the internal sphincter. The cataract blade is then rotated, so that the blade faces the lumen of the anal canal. With the surgeon’s index finger in the anal canal, the cataract blade is advanced toward the index finger so as to divide the internal sphincter, but not the anal mucosa (Fig. 1). A small tampon is placed in the anal canal to prevent hematoma.

Open Internal Sphincterotomy

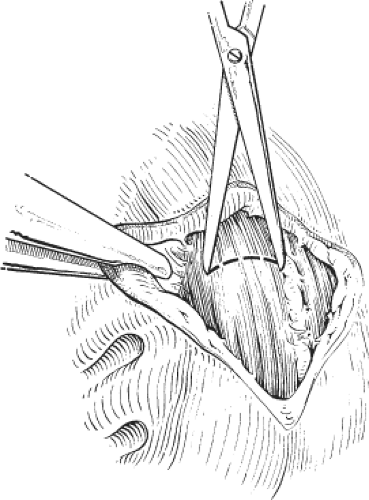

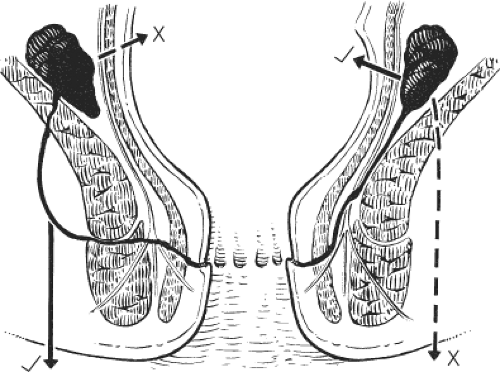

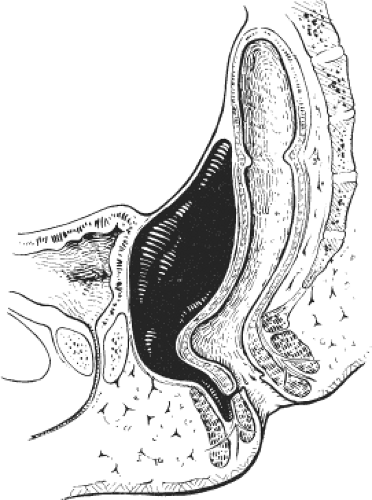

This is the author’s preferred surgical procedure. The patient may be placed in the prone jackknife or the lithotomy position, depending on the surgeon’s preference. The lateral aspects of the submucosal and intersphincteric planes are infiltrated with a local anesthetic and a weak adrenaline solution. An anal speculum is inserted to expose the lateral aspect of the anal canal. A circumanal incision is made just inside the anal canal and below the dentate line for a length of approximately 1.0 to 1.5 cm. Scissors are used to develop the submucosal plane so that the anal mucosa can be lifted from the internal sphincter and to develop the intersphincteric plane so that there can be no damage to the external sphincter. Once the lower fibers of the internal sphincter have been clearly separated from other structures, internal sphincterotomy consists of dividing the internal sphincter with scissors for a length of <2 cm (Fig. 2). The results of the closed and open sphincterotomy are comparable. Complete relief of pain and healing of the fissure is recorded in 70% to 90% of patients. It is hardly ever necessary to contemplate a second sphincterotomy for patients with persistent symptoms and in any event this would not be advised on account of the very high risk of permanent incontinence with a second sphincterotomy.

We never advocate posterior sphincterotomy or excision of the anal fissure, sometimes termed fissurectomy, because these operations may be complicated by a gutter deformity in the anal canal and thus result in soiling and impaired continence.

Anorectal Abscess

Anorectal sepsis usually presents with anal pain, swelling, and fever. There may be associated swelling and discharge around or within the anal canal. Approximately 30% of patients give a history of a previous episode of anorectal sepsis that has spontaneously discharged or required surgical drainage. Constitutional symptoms are common, and swelling is obvious in patients with ischiorectal abscess, because large volumes of pus under tension give rise to fever, malaise, anorexia, and weight loss. By contrast, swelling may not be evident in patients with intersphincteric and submucous abscesses; similarly, patients with supralevator abscess may have no swelling but have constitutional symptoms. In secondary anorectal sepsis, there may be a history of AIDS, pelvic inflammatory disease, Crohn’s disease, malignancy, or previous anal surgery.

Causes

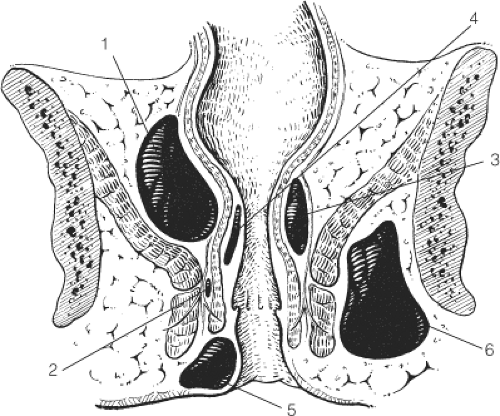

Anorectal sepsis arises from an infection in an anal gland or as a skin infection. Acute infection of an anal gland results in a chronic

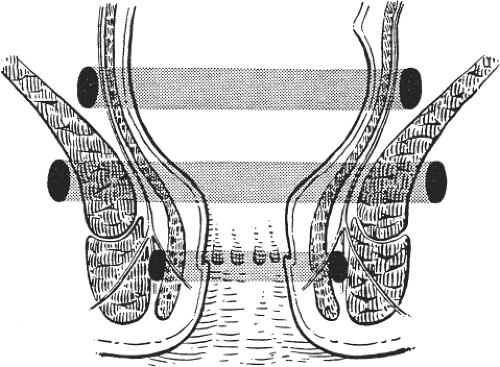

intersphincteric collection of pus that spreads upward in the intersphincteric plane causing a supralevator abscess, or downward in the intersphincteric plane causing a perianal abscess. Alternatively, pus may spread through the external sphincter and result in an ischiorectal abscess or may spread through the internal sphincter and result in submucous abscess. Occasionally, as a result of surgical intervention, pus may spread through the levators and cause supralevator collections of pus (Fig. 3).

intersphincteric collection of pus that spreads upward in the intersphincteric plane causing a supralevator abscess, or downward in the intersphincteric plane causing a perianal abscess. Alternatively, pus may spread through the external sphincter and result in an ischiorectal abscess or may spread through the internal sphincter and result in submucous abscess. Occasionally, as a result of surgical intervention, pus may spread through the levators and cause supralevator collections of pus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Suprasphincteric abscess. (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

Anorectal sepsis from an infection of an anal gland originates from intestinal organisms; thus, the predominant organisms recovered from culture are Escherichia coli and other Gram-negative aerobic bacteria or anaerobic organisms from the large bowel, particularly Bacteroides species.

Some perianal abscesses arise from an infection in the skin and are merely a manifestation of a boil, furuncle, or carbuncle around the anal canal. True skin infections are almost always staphylococcal in origin and are not associated with an internal communication with the anal canal. Thus, culture of pus is helpful in establishing whether an anorectal abscess may have a coexisting anal fistula. Anorectal abscess with intestinal organisms is associated with an underlying anal fistula in 70% of patients. A fistulous communication with the anal canal virtually never occurs in patients with staphylococcal anorectal sepsis.

Fig. 4. Classification of anorectal sepsis. (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

The five classic sites of anorectal sepsis are (in order of frequency): (a) perianal (60%), (b) ischiorectal (20%), (c) intersphincteric (5%), (d) supralevator (4%), and (e) submucosal (1%) (Fig. 4). Supralevator abscesses may occur as a result of upward spread in the intersphincteric space or as a result of over enthusiastic surgical intervention to drain an ischiorectal abscess, creating a track through the levators. Anterior supralevator abscesses are more common in women and posterior supralevator abscesses are more common in men. Supralevator abscess may occur as a result of disease in the pelvis, such as appendicitis, gynecologic sepsis, colorectal cancer, diverticular disease, or Crohn’s disease, or as a result of trauma to the large bowel.

Spread of anorectal sepsis may also occur circumferentially in the three spaces surrounding the anal canal: supralevator space, ischiorectal fossa, and intersphincteric space (Fig. 5).

Diagnosis of anorectal sepsis is usually obvious clinically by a large, painful, red swelling over the buttock (ischiorectal abscess) or a small, well-circumscribed, red, tender fluctuant swelling near the anal margin (perianal abscess). Inspection may fail to reveal

intersphincteric sepsis or supralevator abscess. The presence of pus may be confirmed by needle aspiration, but in patients who do not have an obvious collection in the ischiorectal fossa or the perianal region, diagnosis may require examination under anesthesia, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or anal ultrasonography. In our experience, anal ultrasonography is helpful in identifying intersphincteric and submucous collections, but it is incapable of imaging sepsis in the supralevator space or in the ischiorectal fossa. MRI has become the investigation of choice for obscure and complex anorectal sepsis.

intersphincteric sepsis or supralevator abscess. The presence of pus may be confirmed by needle aspiration, but in patients who do not have an obvious collection in the ischiorectal fossa or the perianal region, diagnosis may require examination under anesthesia, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or anal ultrasonography. In our experience, anal ultrasonography is helpful in identifying intersphincteric and submucous collections, but it is incapable of imaging sepsis in the supralevator space or in the ischiorectal fossa. MRI has become the investigation of choice for obscure and complex anorectal sepsis.

Proctosigmoidoscopy should be performed to exclude sepsis from a primary cause, such as AIDS, pelvic sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease (particularly Crohn’s disease), anal malignancy, and sepsis resulting from previous anal surgery.

Conservative Therapy

Conservative treatment is never advised for treatment of anorectal sepsis. The practice of prescribing antimicrobial agents in the hope of resolving infection around the anal canal should be discouraged. Antibiotic therapy simply delays adequate surgical drainage. Delay in drainage results in chronic infection and destruction of tissue, particularly if there is synergistic gangrene and necrotizing fasciitis. Delay is often complicated by extensive fibrosis and long-term impairment of function, with incontinence and stricture.

Our preference is early surgical drainage in almost all instances, except possibly in patients with hematological disorders associated with neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. The principles of drainage are accurate localization and complete drainage. Careful examination under anesthesia is essential to define the site of infection. Pus is sent for immediate culture, and patients are carefully followed to identify recurrent sepsis or an underlying anal fistula. We do not attempt to identify an underlying anal fistula at the time of primary drainage, because we believe that an attempt to identify and treat the underlying fistula may result in anal destruction and compromise continence. Thus, our policy is careful follow-up and reinvestigation only if there is clinical evidence of underlying fistula. Postoperatively, patients are given analgesics and a mild laxative to prevent postoperative constipation. Careful follow-up is necessary, because there is a 30% risk of recurrence of sepsis and a 40% risk of subsequent anal fistula. In some patients, there may be evidence of underlying inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic sepsis, or sexually transmitted disease, which may become evident only during follow-up.

Drainage of Perianal Abscess

A small perianal abscess is incised using a cruciate or saucer-shaped incision so that pus can be adequately drained. A drainage tube is not inserted. The procedure may be performed in the physician’s office under caudal or general anesthesia (Fig. 6).

Ischiorectal Abscess

A cruciate incision is made to the site of maximum swelling, pus is allowed to drain, and a finger is gently inserted into the ischiorectal fossa to break down any loculi. It is essential to check that there has been no posterior circumferential spread to the opposite side. A drain is not usually left in situ unless the ischiorectal abscess is bilateral or chronic. These operations are much better performed with the patient under general anesthesia. Great care must be taken not to damage the levator plate, which will convert an ischiorectal abscess into ones with a supralevator extension (Fig. 7).

Drainage of Intersphincteric Abscess

These abscesses are difficult to identify and to localize, and examination with the patient anesthetized is essential. A small incision is made transversely just inside the anal canal and below the dentate line. The intersphincteric space is identified and, with

scissor dissection, the plane between the internal and external sphincters is exposed. If the intersphincteric abscess is well localized, the internal sphincter is divided and the abscess is drained. A small mushroom catheter is left in situ and sutured into position. Failure to insert a mushroom catheter results in contraction of the sphincter muscles because of postoperative pain and impaired drainage, causing recurrent sepsis.

scissor dissection, the plane between the internal and external sphincters is exposed. If the intersphincteric abscess is well localized, the internal sphincter is divided and the abscess is drained. A small mushroom catheter is left in situ and sutured into position. Failure to insert a mushroom catheter results in contraction of the sphincter muscles because of postoperative pain and impaired drainage, causing recurrent sepsis.

Drainage of Supralevator Abscess

Posterior supralevator abscesses are drained in the manner described for drainage of intersphincteric abscess. The intersphincteric plane is opened posteriorly. It is exposed inside and beyond the puborectalis sling so that the supralevator abscess in the postanal space can be adequately drained. It is essential to suture a mushroom catheter into position. Failure to do so results in recurrent sepsis because of contraction of the puborectalis and sphincters.

Anterior supralevator abscesses are also drained with the patient under general anesthesia using the intersphincteric plane through a transverse anal incision anteriorly. Anterior supralevator abscesses tend to be much more superficial. Again, it is essential to leave a mushroom catheter in situ. Failure to do so results in a high incidence of recurrent sepsis (Fig. 8).

Drainage of Submucous Abscess

With the patient anesthetized, the abscesses are drained using an anal speculum. Drainage involves opening the mucosa above the swelling so that pus can be discharged. It is often wise to combine the operation with internal sphincterotomy to reduce anal spasm postoperatively to facilitate efficient drainage, which might otherwise lead to a high incidence of persistent sepsis.

Anorectal Fistulae

Anorectal fistulae present with purulent discharge around the anus and from within the anal canal. Discharge is associated with impaired anal hygiene and soiling. There may be a history of recurrent episodes of anorectal sepsis that have required surgical drainage or that have spontaneously ruptured. In some patients, there may be a history of sexually transmitted disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or malignancy. It is important to exclude rectal malignancy, skin cancer, and a growth complicating long-standing anorectal fistula. Inspection in most cases reveals an external opening around the anal canal but, particularly in patients with intersphincteric fistulae, there may be no apparent external opening.

Causes

Most anorectal fistulae are secondary to cryptoglandular infection caused by enteric bacteria. The anal glands lie in the intersphincteric space, and their ducts enter the anal canal to discharge at the dentate line. The acini ramify in the intersphincteric space and some penetrate the internal sphincter muscle and the external sphincter. Pus spreads in the intersphincteric space upward, downward, or laterally and results in an abscess, commonly in the perianal region or in the ischiorectal fossa. These abscesses are treated by drainage or by spontaneous discharge. Once the anorectal sepsis has drained, there is a potential communication from the perianal region to the anal canal at the dentate line. Continued communication between the two epithelial surfaces results in anorectal fistulae. For many patients, drainage is delayed, or surgical treatment complicates the course of the fistula and results in circumferential spread, if there has been delay, or in high blind tracks if there has been aggressive and inexperienced surgical intervention.

Although most anorectal fistulae are primarily caused by anoglandular infections, a few are secondary to other diseases. Congenital fistulae may occur and may be associated with inclusion dermoids. Chronic pelvic sepsis may result in fistulae if there is an infective process that drains through the levator plate to the perineum from diverticular disease, Crohn’s disease, large-bowel malignancy, or irradiation injury. Secondary fistulae are common in Crohn’s disease and are common manifestations, but secondary fistulae should not be regarded as specific, because 7% of patients with ulcerative colitis also develop perianal fistulae. Anorectal fistulae may occasionally complicate tuberculosis, actinomycosis, anal fissure, rectal carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and foreign bodies around the anal canal.

Anorectal fistulae are categorized as primary or secondary. Primary fistulae are further classified by (a) the course of the primary track, which is usually subdivided into intersphincteric, transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphincteric; (b) whether there are high blind tracks; and (c) whether there is any evidence of circumferential involvement. Thus, a three-dimensional drawing of the perineum and the anorectum in the coronal and sagittal planes with the smooth and circular muscular sphincter apparatus displayed is necessary to thoroughly identify the course of an anorectal fistula. It must be evident from this complicated classification that treatment of such anorectal fistulae must be directed on an individual basis to the particular anatomic distribution of the track, the presence of high blind extensions, and circumferential spread (Fig. 5).

Accurate diagnosis of the site, extent, and complexity of the fistula is essential for a successful treatment. Preoperative diagnosis includes careful anal inspection and digital examination, particularly to identify areas of induration and external openings that may discharge pus during rectal examination; proctoscopy to identify the internal

opening and any associated anal papillae or skin tags; and proctosigmoidoscopy to exclude primary colorectal disorders, particularly Crohn’s disease.

opening and any associated anal papillae or skin tags; and proctosigmoidoscopy to exclude primary colorectal disorders, particularly Crohn’s disease.

Fig. 9. Retrograde probing of an anal fistula. (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

Anorectal ultrasound may be helpful in delineating the course of intersphincteric fistulae, but the focal length of the 7-MHz probe is not sufficiently deep to image beyond the external sphincter or puborectalis. MRI is regarded as the investigation of choice for the delineation of anorectal fistulae, particularly in complex transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphincteric fistulae.

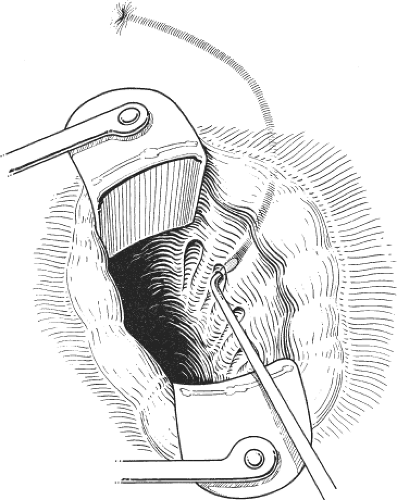

It is essential that all patients with anorectal fistulae be examined carefully under anesthesia. The fistula track should be identifiable by a combination of palpation for induration and gentle probing of the fistula track. Often, a combination of external and internal probing is necessary to identify the track (Fig. 9). Injection of methyl blue may be helpful but is rather messy, and povidone-iodine is preferred if the technique is to be used. Fistulography may sometimes help delineate the course of a complex anorectal fistula.

There are a wide variety of techniques for the treatment of anorectal fistulae. We prefer fistulotomy, or “lay open” for low-lying tracks that do not traverse skeletal muscle and seton fistulotomy for almost all other fistula tracks that involve the sphincters or puborectalis. Occasionally, fistulectomy (excision of the fistula track) with an anorectal advancement flap is advised for specialized fistulae, particularly extrasphincteric and rectovaginal fistulae where sphincter function is to be preserved but there is a high rate of recurrent sepsis. Other methods include the fibrin plug, which preserves sphincter function and needs to be sutured into position or otherwise it is likely to migrate and fall out. Early results using the fibrin plug appear to be promising but the same could have been said about methods using glue, thus only time will tell whether the claims made by the manufacturers of the anal plug will prove to be comparable or superior to conventional therapy. Consequently, the results of randomized controlled trials will be needed before the role of the anal plug will be known.

Preoperative bowel preparation with a phosphate enema may be used in complex fistulae. Postoperative management requires the provision of adequate analgesics and laxatives to prevent postoperative constipation. Rigorous follow-up is essential for these patients, as there is a 10% to 20% risk of subsequent anorectal sepsis complicated by recurrent anorectal fistulae. Follow-up is particularly important for patients with a seton as these frequently require to be changed. Follow-up is also essential to identify any evidence of underlying disease, particularly in patients with complex anorectal fistulae.

Fistulotomy (Lay Open)

The principle of fistulotomy is the identification of the fistula track so that the track can be laid open. Clearly, this method of treatment is inappropriate for patients with extrasphincteric and suprasphincteric fistulae, because the fistula track lies outside the sphincter mechanisms, and any lay-open procedure divides the striated sphincter complex and renders the patient incontinent, usually from a rigid gutter causing soiling. Fistulotomy is thus appropriate only for simple intersphincteric fistulae and low transsphincteric fistulae.

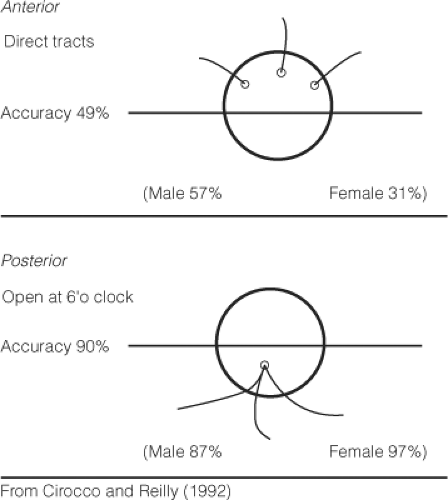

The first and most important maneuver is the demonstration of the primary fistula track. Probing is thus used to define the course of the track and should also identify high blind tracks. If the external opening is located obliquely from the internal opening, there will be some element of circumferential involvement. The course of simple fistulae usually obeys the Goodsall’s rule (Fig. 10). Thus, an external opening lying posterior to the horizontal plane is likely to open into the anal canal at the midline posteriorly, whereas an external opening lying anterior to the horizontal line is more likely to run directly into the anal canal. A malleable fistula probe is gently passed through the fistula track. By use of diathermy, the perianal skin and anal epithelium are divided. The internal sphincter, if involved, is identified and divided. If there is striated muscle superficial to the fistula track, this may be divided provided it consists of only a few fibers. However, if a substantial amount of striated muscle is encountered superficial to the fistula track, division of the muscle is not advisable and a seton is inserted. If a high blind track is found, the track should be loosely curetted and adequately drained through the fistulotomy incision. Provided the fistula track can be safely laid open, any bleeding from the edges should be secured by cautery and gauze dressing applied.

Patients may have more than a single external opening. Multiple anterior openings usually have separate internal openings, which should be dealt with in the same manner by defining all fistula tracks and opening them, provided that this does not involve division of a large amount of striated muscle (Fig. 11). For multiple posterior anal fistulae, the tracks usually open at the same site in the midline posteriorly. Furthermore, under these circumstances, there may be a small supralevator collection in the postanal space. Again, each fistula track is opened, provided that

this does not involve the division of a large amount of striated muscle. The internal opening is then further explored in the intersphincteric plane to ensure that there is no supralevator component. Any redundant skin is excised, and an antiseptic dressing is applied.

this does not involve the division of a large amount of striated muscle. The internal opening is then further explored in the intersphincteric plane to ensure that there is no supralevator component. Any redundant skin is excised, and an antiseptic dressing is applied.

Seton Fistulotomy

The principle of seton fistulotomy is that any striated muscle lying superficial to the fistula track is encircled by a length of soft rubber or latex tubing, or by using a Prolene or silk tie. The seton is tied loosely and left in situ. Over the following weeks, the striated muscle is slowly divided by the presence of the seton. However, because the process of striated muscle division is relatively slow, the muscle does not therefore spring apart, leaving a defect (gutter), but heals behind the process of division. Consequently, fibrous tissue is laid down in the bed of the fistula as it is slowly divided. This process avoids the gutter deformity, which is usually associated with soiling and minimizes the risks of impaired continence. The problem with this technique is that treatment may take a number of weeks and follow-up is essential. On the other hand, preservation of continence is much better than with fistulotomy, especially for mid or high transsphincteric fistula.

Fig. 11. Laying open of a low-lying transsphincteric fistula. (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

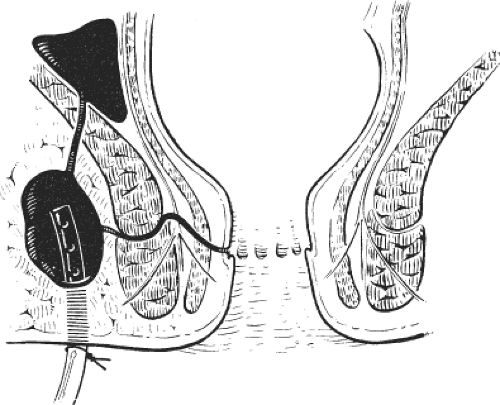

The fistula track is identified by using a probe, as described in the previous section. The perianal skin and the skin of the anal canal are divided. The internal sphincter is also divided, but the striated muscle lying superficial to the fistula track is preserved. Thus, a substantial amount of the fistula is laid open. A vascular rubber sling (sloop) is threaded through the eye of the fistula probe and is delivered around the striated muscle as a seton, but other materials may be used (e.g., latex and Teflon). The seton is tied with multiple knots, and the end is sutured beyond the last knot so that it cannot become untied with patient movement during follow-up (Fig. 12). Usually, the patient can be discharged on the same day. Arrangements for follow-up should be made.

At the first follow-up, the seton usually remains in situ but has already partially divided the striated muscle superficial to the fistula track. A simple method of tightening the seton is by the application of rubber bands beyond the first knot. Commonly, five or six bands should be applied to ensure that the seton snuggly surrounds the residual striated muscle. Alternatively, the seton is replaced and retied. A second follow-up in 1 week should then be scheduled. At the second visit, the seton has usually completely divided the striated muscle and has fallen out. If, on the other hand, it has not fallen out, the seton is replaced and follow-up continues until the track has been divided. Thus, the fistula track is slowly divided during a period of 1 to 6 weeks. The technique is remarkably successful at preserving sphincter function and avoiding the development of a gutter deformity. Careful follow-up is essential to detect recurrent fistula. Careful attention to the wound is also essential to ensure that it does not become infected, and that there is no bridging over the fistulotomy site during healing.

Fistulectomy and Anorectal Advancement Flap

Although anorectal advancement with excision of the track should preserve continence and avoid soiling, despite spectacular results reported by some, in this author’s experience, sepsis and recurrent fistula are common. In future, the anal plug may replace this technique.

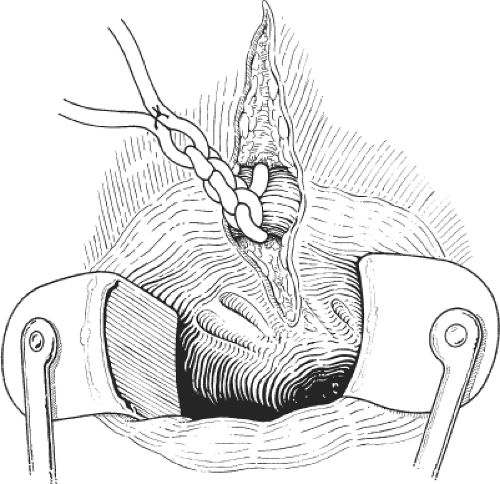

The first part of the operation involves fistulectomy, that is, excision of the fistula track. This can be technically difficult and involves careful dissection using a fine scalpel or diathermy point around the fistula track through to its internal opening. Side tracks must be similarly excised. In complex fistulae, three or four separate fistula tracks will need to be cored out. The defect in the external sphincter may require closure, and some form of drainage procedure is usually needed. The next step is to close the internal opening, usually with an anorectal advancement flap.

The anorectal advancement flap is simply a way of closing the internal opening of the excised transsphincteric fistula. A wide-based curvilinear flap, consisting of mucosa, submucosa, and rectal wall is advanced from above so as to close the internal component of the fistula without tension, while draining any coexisting sepsis. The technique is fully described and illustrated later in the section on “Rectovaginal Fistula.” However, in anorectal fistula, unlike rectovaginal fistula, there is an external perineal orifice that should be thoroughly drained (Fig. 13).

Complete Lay Open and Repair

Extrasphincteric and suprasphincteric fistulae may be treated by total fistulotomy (if setons are not used) while ensuring that the divided and striated muscle is marked so that it can be identified at a later date. Once all of the infection has been cleared, a standard sphincter repair is then performed. The alternative is to perform the reconstruction at the time of the primary lay-open procedure. The problem with sphincter repair under these circumstances is that the primary sphincter repair may break down because of coexisting sepsis. We therefore do not advise the technique in the majority of cases and believe that it has been superseded by fistulectomy and advancement flap closure or the anal plug.