The developmental abnormalities characteristic of any one trisomic state must be determined by the extra dosage of the particular genes on the additional chromosome. Knowledge of the specific relationship between the extra chromosome and the consequent developmental abnormality has been limited to date. Current research, however, is beginning to localize specific genes on the extra chromosome that are responsible for specific aspects of the abnormal phenotype, through direct or indirect modulation of patterning events during early development (see Chapter 14). The principles of gene dosage and the likely role of imbalance for individual genes that underlie specific developmental aspects of the phenotype apply to all aneuploid conditions; these are illustrated here in the context of Down syndrome, whereas the other conditions are summarized in Table 6-2.

Down Syndrome

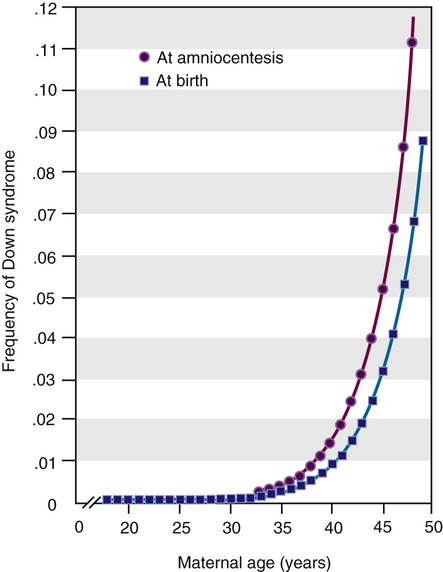

Down syndrome is by far the most common and best known of the chromosome disorders and is the single most common genetic cause of moderate intellectual disability. Approximately 1 child in 850 is born with Down syndrome (see Table 5-2), and among liveborn children or fetuses of mothers 35 years of age or older, the incidence of trisomy 21 is far higher (Fig. 6-1).

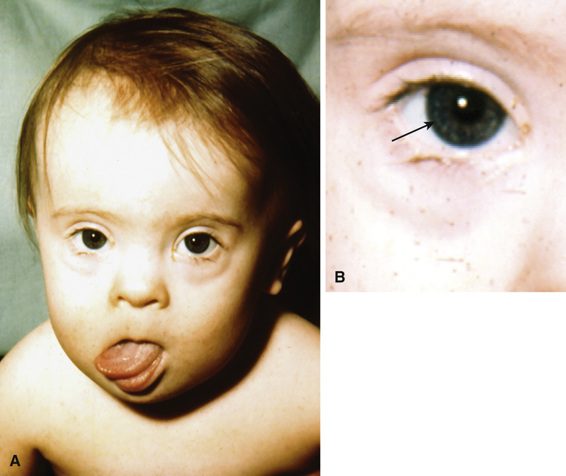

Down syndrome can usually be diagnosed at birth or shortly thereafter by its dysmorphic features, which vary among patients but nevertheless produce a distinctive phenotype (Fig. 6-2). Hypotonia may be the first abnormality noticed in the newborn. In addition to characteristic dysmorphic facial features (see Fig. 6-2), the patients are short in stature and have brachycephaly with a flat occiput. The neck is short, with loose skin on the nape. The hands are short and broad, often with a single transverse palmar crease (“simian crease”) and incurved fifth digits (termed clinodactyly).

A major cause for concern in Down syndrome is intellectual disability. Even though in early infancy the child may not seem delayed in development, the delay is usually obvious by the end of the first year. Although the extent of intellectual disability varies among patients from moderate to mild, many children with Down syndrome develop into interactive and even self-reliant persons, and many attend local schools.

There is a high degree of variability in the phenotype of Down syndrome individuals; specific abnormalities are detected in almost all patients, but others are seen only in a subset of cases. Congenital heart disease is present in at least one third of all liveborn Down syndrome infants. Certain malformations, such as duodenal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, are much more common in Down syndrome than in other disorders.

Only approximately 20% to 25% of trisomy 21 conceptuses survive to birth (see Table 5-2). Among Down syndrome conceptuses, those least likely to survive are those with congenital heart disease; approximately one fourth of the liveborn infants with heart defects die before their first birthday. There is a fifteen fold increase in the risk for leukemia among Down syndrome patients who survive the neonatal period. Premature dementia, associated with the neuropathological findings characteristic of Alzheimer disease (cortical atrophy, ventricular dilatation, and neurofibrillar tangles), affects nearly all Down syndrome patients, several decades earlier than the typical age at onset of Alzheimer disease in the general population.

As a general principle, it is important to think of this constellation of clinical findings, their variation, and likely outcomes in terms of gene imbalance—the relative overabundance of specific gene products; their impact on various critical pathways in particular tissues and cell types, both early in development and throughout life; and the particular alleles present in a particular patient’s genome, both for genes on the trisomic chromosome and for the many other genes inherited from his or her parents.

The Chromosomes in Down Syndrome

The clinical diagnosis of Down syndrome usually presents no particular difficulty. Nevertheless, karyotyping is necessary for confirmation and to provide a basis for genetic counseling. Although the specific abnormal karyotype responsible for Down syndrome usually has little effect on the phenotype of the patient, it is essential for determining the recurrence risk.

Trisomy 21.

In at least 95% of all patients, the Down syndrome karyotype has 47 chromosomes, with an extra copy of chromosome 21 (see Fig. 5-9). This trisomy results from meiotic nondisjunction of the chromosome 21 pair. As noted earlier, the risk for having a child with trisomy 21 increases with maternal age, especially after the age of 30 years (see Fig. 6-1). The meiotic error responsible for the trisomy usually occurs during maternal meiosis (approximately 90% of cases), predominantly in meiosis I, but approximately 10% of cases occur in paternal meiosis, often in meiosis II. Typical trisomy 21 is a sporadic event, and thus recurrences are infrequent, as will be discussed further later.

Approximately 2% of Down syndrome patients are mosaic for two cell populations—one with a normal karyotype and one with a trisomy 21 karyotype. The phenotype may be milder than that of typical trisomy 21, but there is wide variability in phenotypes among mosaic patients, presumably reflecting the variable proportion of trisomy 21 cells in the embryo during early development.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree