Anatomy of the Kidneys, Ureter, and Bladder

Richard L. Drake

Jennifer M. McBride

Kidneys

The kidneys are located in the retroperitoneal connective tissue of the posterior abdominal wall. They develop as pelvic organs that ascend to their final position in the abdomen. The kidneys are bean-shaped structures with a reddish-brown coloration and are approximately 11 to 12 cm long, 5.0 to 7.5 cm wide, and 2.5 to 3.0 cm thick. The left kidney is usually somewhat longer and narrower than the right kidney. Their location in the posterior abdominal wall is usually between the upper border of T-12 and L-2. However, the right kidney is usually slightly lower than the left kidney because of the presence of the liver.

Relationships and Fascias

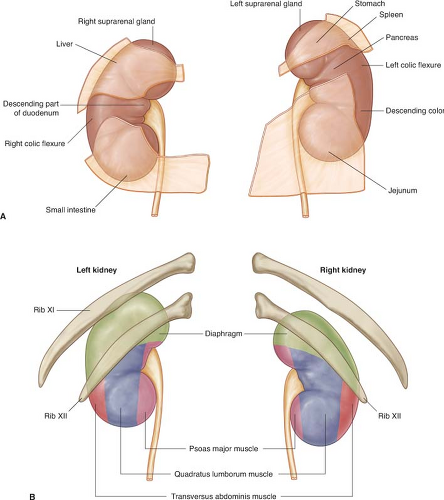

The location of the kidneys against the posterior abdominal wall provides development of unique relationships with numerous other structures. Structures anterior to the right kidney are the suprarenal gland, the liver, the second part of the duodenum, the right colic flexure, and the small intestine (Fig. 1A). Structures posterior to the right kidney include the diaphragm, the costodiaphragmatic recess, the 12th rib, the psoas major muscle, the quadratus lumborum muscle, the transversus abdominis muscle, and the subcostal, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves (Fig. 1B). Structures anterior to the left kidney include the suprarenal gland, the spleen, the stomach, the body (or tail) of the pancreas, the left colic flexure, and the small intestine (Fig. 1A). The listed structures lie directly against the fascias covering the kidney without any intervening tissues except for the liver, the stomach, the spleen, and the small intestine, which are covered with peritoneum. The structures listed as posterior to the right kidney are also posterior to the left kidney, with the addition of the 11th rib because of the higher position of the left kidney (Fig. 1B). Thus, numerous structures must be considered in any surgical approach to the kidneys.

The fascias covering the kidneys are unique. Enclosing the renal parenchyma is a fibrous tissue called the renal capsule. This layer of tissue is lightly bound to the kidneys and can be removed easily except in certain disease processes. Immediately adjacent to the renal capsule is the perinephric (perirenal) layer of fat (Fig. 2). This layer covers the kidneys and the ureter and is called the adipose capsule. Continuing outward is a membranous condensation of the extraperitoneal connective tissue called the renal (Gerota) fascia (Fig. 2). This specialized membrane separates the perirenal fat from the adipose tissue covering the posterior abdominal wall and must be incised in any operation, whether an anterior or posterior approach is used. The renal fascia consists of anterior and posterior layers that surround the kidneys and the suprarenal gland, usually sending an intervening septum between the two structures. Moving laterally, the anterior and posterior layers may fuse and become continuous with the transversalis fascia. Medially, the posterior layer fuses with the fascia covering the psoas muscle, and the anterior layer may fuse with the sheaths of the blood vessels in the area or cross to the opposite side and fuse with the anterior layer from that side (Fig. 2). Superiorly, the anterior and posterior layers fuse after passing over the suprarenal gland and, inferiorly, the layers also fuse, except where the ureter passes through these tissues. Because of the opening around the ureter, infections around the kidneys may descend into the pelvis and vice versa. Finally, outside the renal fascia is the paranephric (pararenal) fat (Fig. 2). This is a layer of adipose tissue on the posterior abdominal wall and is usually in a posterolateral position.

Structure

The renal parenchyma consists of the outer cortex and the inner medulla (Fig. 3). The cortex is an outer, pale, continuous broad band of tissue. It is a dense, homogeneous tissue and consists of renal corpuscles and convoluted portions of renal tubules. The medulla is an inner layer of discontinuous tissue caused by the inward projections of cortical tissue called the renal columns. The medulla is darker brown than the cortex and is composed of the renal pyramids. The renal pyramids appear to have longitudinal striations, which extend into the cortex as medullary rays. Each pyramid contains the descending and ascending limbs of the renal tubules and the collecting tubules. The apex of each pyramid is called a renal papilla, and it projects into a minor calyx, which is a subdivision of the renal pelvis.

The medial margin of each kidney is occupied by the hilum. The hilum expands into a central cavity called the renal sinus and is the site of entrance or exit for blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. It transmits, from anterior to posterior, the renal vein, the anterior branch of the renal artery, the ureter, and the posterior branch of the renal artery. It also contains fat and the renal pelvis. The renal pelvis is the expanded upper end of the ureter. It divides into two or three major calyces that further subdivide into many minor calyces. Each minor calyx is indented by a renal papilla. The renal pelvis continues inferiorly and tapers to a narrow tube that becomes the ureter. The ureteropelvic junction is rather indefinite but is usually referred to as located opposite the lower pole of the kidneys.

Vascular Supply and Lymphatics

The kidneys are supplied by the renal arteries, which arise from the lateral aspect of

the aorta just inferior to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery (usually between L-1 and L-2). On occasion, the right renal artery may arise a little higher than the left and has a unique pathway to the right kidney in that it passes posterior to the inferior vena cava as it crosses the posterior abdominal wall. As each renal artery approaches the renal pelvis, it divides into anterior and posterior branches that pass on either side of the renal pelvis and major calyces (Fig. 3). This provides a somewhat bloodless horizontal plane through the kidney because the anterior branch supplies the anterior half of the organ, and the posterior branch supplies the posterior half of the organ. Additional accessory renal arteries may be found entering the hilum or extrahilar regions. Generally, the accessory arteries do not anastomose with the major renal arteries and may arise from the aorta, the renal artery, or from a different vessel.

the aorta just inferior to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery (usually between L-1 and L-2). On occasion, the right renal artery may arise a little higher than the left and has a unique pathway to the right kidney in that it passes posterior to the inferior vena cava as it crosses the posterior abdominal wall. As each renal artery approaches the renal pelvis, it divides into anterior and posterior branches that pass on either side of the renal pelvis and major calyces (Fig. 3). This provides a somewhat bloodless horizontal plane through the kidney because the anterior branch supplies the anterior half of the organ, and the posterior branch supplies the posterior half of the organ. Additional accessory renal arteries may be found entering the hilum or extrahilar regions. Generally, the accessory arteries do not anastomose with the major renal arteries and may arise from the aorta, the renal artery, or from a different vessel.

The venous drainage of the kidneys consists of anastomosing channels forming a

single renal vein that exits at the hilum. Most tributaries of the renal vein pass anterior to the renal pelvis, but on occasion one may pass posterior to this structure. After exiting the hilum, the left renal vein passes anterior to the aorta and posterior to the superior mesenteric artery as it approaches the inferior vena cava. The right renal vein has a short, direct path to the inferior vena cava and enters this vessel at approximately the same level as the left renal vein.

single renal vein that exits at the hilum. Most tributaries of the renal vein pass anterior to the renal pelvis, but on occasion one may pass posterior to this structure. After exiting the hilum, the left renal vein passes anterior to the aorta and posterior to the superior mesenteric artery as it approaches the inferior vena cava. The right renal vein has a short, direct path to the inferior vena cava and enters this vessel at approximately the same level as the left renal vein.

Fig. 4. The path of the ureter as it passes down the posterior abdominal wall toward the bladder. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM, Tibbitts R, Richardson PE. Gray’s Atlas of Anatomy. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone [Elsevier], 2008, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|