Anatomy of the Colon and Rectum

Richard L. Drake

Jennifer M. McBride

Introduction

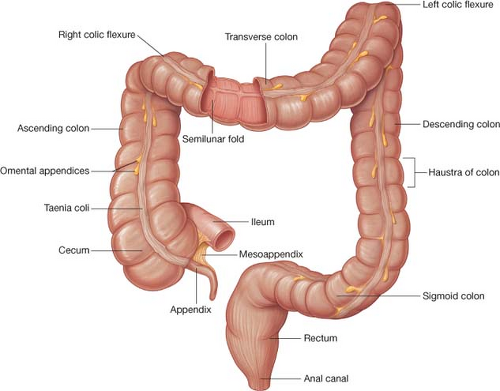

The large intestine extends from the ileocecal valve to the anus and consists of the cecum, the appendix, the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colons, the rectum and the anal canal (Fig. 1). Functionally, the large intestine is involved in the conversion of the liquid contents of the ileum into semisolid feces. Throughout its length, there is an alternating pattern of fixed and mobile components. The cecum and the transverse and sigmoid colons possess considerable mobility, whereas the ascending and descending colons are fixed to the posterior abdominal wall. The rectum is relatively immobile with its upper third covered by peritoneum on the anterior and lateral surfaces, the middle third covered only on the anterior surface, and the lower third has no covering of peritoneum. The general characteristics of the colon are its large caliber; the presence of pendant-shaped bodies of fat enclosed by peritoneum, called omental appendices (appendices epiploicae); and the longitudinal muscle in its walls, which forms three narrow, ribbon-like bands called taeniae coli. The locations of the taeniae are useful landmarks and are specific in relation to the position of the colon itself. The posterior taenia, or tenia omental, is found on the posterolateral border of

the ascending and descending colons and the anterior border of the transverse colon. The anterior taenia, or tenia libera, is visible on the exposed or antimesenteric border of the cecum and the ascending, descending, and sigmoid colons, but it is located on the inferior surface of the transverse colon and covered by the attachment of the greater omentum. The lateral taenia, or tenia mesocolica, is located on the posteromedial side of the cecum and the ascending, descending, and sigmoid colons, and on the posterior border of the transverse colon at the attachment of the transverse mesocolon. Between the taeniae coli the colon is sacculated, forming the haustra of colon.

the ascending and descending colons and the anterior border of the transverse colon. The anterior taenia, or tenia libera, is visible on the exposed or antimesenteric border of the cecum and the ascending, descending, and sigmoid colons, but it is located on the inferior surface of the transverse colon and covered by the attachment of the greater omentum. The lateral taenia, or tenia mesocolica, is located on the posteromedial side of the cecum and the ascending, descending, and sigmoid colons, and on the posterior border of the transverse colon at the attachment of the transverse mesocolon. Between the taeniae coli the colon is sacculated, forming the haustra of colon.

Cecum and Appendix

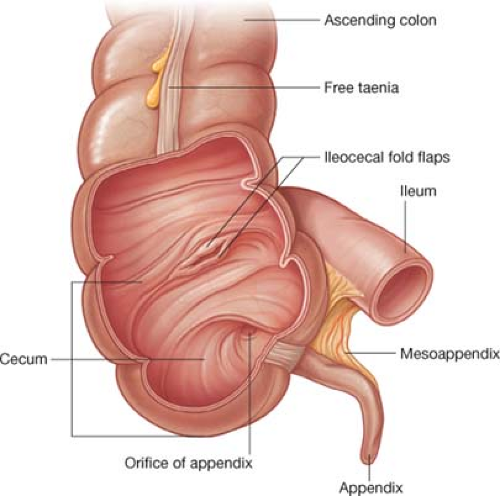

The cecum is the saccular commencement of the colon. It is located in the right iliac fossa, where it lies on the iliacus muscle cranial to the lateral half of the inguinal ligament. At times, it may cross the pelvic brim to lie in the true pelvis. Anteriorly, it usually is in contact with the anterior abdominal wall. Superiorly, it is continuous with the ascending colon, and at some point along its medial border, the ileum enters it at the ileocecal ostium. This opening is surrounded by two flaps that protrude into the lumen and contain circular muscle derived partly from the ileal musculature and partly from the cecal musculature (Fig. 2). This structure is referred to as the ileocecal valve, but it is questionable whether the valve acts as a functional sphincter. The cecum has no mesentery, even though it is referred to as being an intraperitoneal structure in most individuals, because it has a considerable amount of mobility.

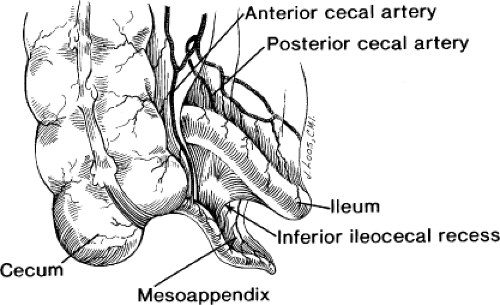

The vermiform appendix takes origin from the posteromedial border of the cecum and can be located by following the anterior taenia to its junction with the other two taeniae (Fig. 1). Its size is variable, 5 to 10 mm in diameter and 8 to 10 cm in length; in most people, it is found in a retrocecal position. The attachment of the appendix is extended along the inferior border of the terminal portion of the ileum by its own mesentery, the mesoappendix (Fig. 3). The appendicular artery and vein are found in this mesentery. The appendix is involved in the formation of several recesses in association with the cecum (Fig. 3). The superior ileocecal recess (fossa of Luschka) lies anterior to the terminal ileum. It is formed by a peritoneal fold, the superior ileocecal or vascular fold, which extends from the mesentery of the terminal ileum, and, after crossing the ileum, it attaches to the lowest part of the colon and cecum. This fold contains the anterior cecal artery. Similarly, the inferior ileocecal recess lies between the mesoappendix and a fold of peritoneum referred to as the inferior ileocecal fold or the bloodless fold of Treves (Fig. 3). This fold extends from the antimesenteric border of the terminal ileum to the base of the appendix or the anterior surface of the mesoappendix, or to both areas. The fold contains no sizable blood vessels. The surface projection of the base of the appendix lies at the junction of the lateral and middle third of a line joining the anterior superior iliac spine with the umbilicus, known as McBurney point. Patients who have acute appendicitis often describe a localized pain near this point.

Ascending Colon

The ascending colon begins at the superior end of the cecum (Fig. 1). This part of the colon has no mesentery and is relatively fixed to the posterior abdominal wall. The upper part of the ascending colon is covered anteriorly by coils of small intestine, but the lower part may come into direct contact with the anterior abdominal wall. Posteriorly, the ascending colon is related to the lower pole of the right kidney and lies on the iliacus muscle and the aponeurotic origin of the transversus abdominis muscle. The kidney and branches of the lumbar plexus separate the ascending colon from the quadratus lumborum muscle.

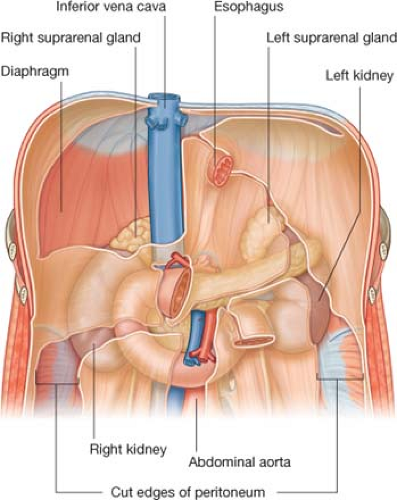

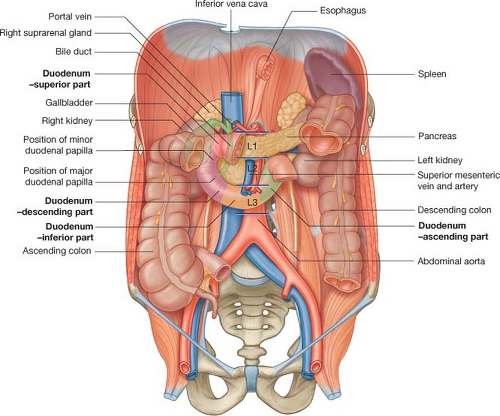

Anterior to the right kidney and immediately inferior to the right lobe of the liver, the ascending colon makes a sharp bend to the left, forming the right colic (hepatic) flexure (Fig. 4). Structures posterior to this flexure include the descending or second part of the duodenum, which is covered by a layer of parietal peritoneum, and the renal, or Gerota, fascia surrounding the right kidney, since the posterior aspect of the hepatic flexure is not covered by peritoneum (Figs. 5 and 6).

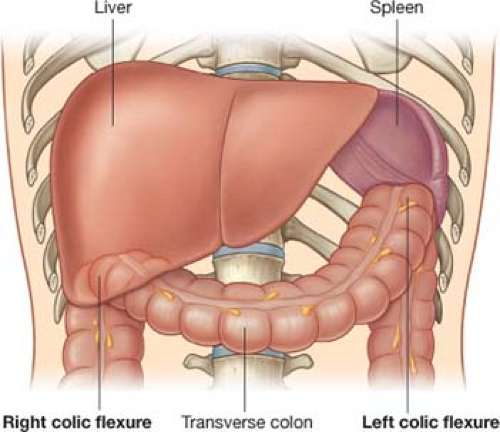

Fig. 4. Right and left colic flexures. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone (Elsevier); 2010.) |

Fig. 5. Structures posterior to the right and left colic flexures. (From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone (Elsevier); 2010.) |

Lateral to the ascending colon is the right paracolic sulcus, or gutter. This depression is formed by a reflection of the peritoneum after it crosses the ascending colon and before it continues onto the posterior abdominal wall. Material can move along this gutter from the appendix to the hepatorenal recess or from the liver into the pelvis. In addition, surgeons can incise the peritoneum along this border, the “white fascial line of Toldt,” to mobilize the ascending colon. The blood vessels and lymphatics lie in the retroperitoneal connective tissue on the medial or posteromedial side of the ascending colon, which, during development, composed the mesentery of the ascending colon. Thus, by mobilizing the ascending colon on this lateral avascular border and raising it toward the midline, the retroperitoneal connective tissue containing the blood vessels and lymphatics can be lifted intact.

Transverse Colon

The transverse colon begins at the right colic flexure (Fig. 1) and passes to the left side, where it ends at the left colic or splenic flexure (Fig. 4). It is intraperitoneal and is suspended from the posterior abdominal wall by the transverse mesocolon. Although its posterior relationships can vary because of its mobility, the transverse colon is usually anterior to the hilus of the right kidney, the descending (second) part of the duodenum, and the head of the pancreas (Fig. 5). Its cranial surface is in contact with the liver, the gallbladder, the greater curvature of the stomach, and the spleen (Fig. 4). Its caudal surface is in contact with the small intestine, and its anterior surface contacts the anterior layers of the greater omentum and the abdominal wall.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree