2 An integrative model of hypnotherapy in clinical practice

INTRODUCTION

Significant shifts in healthcare over the past 20 years have led to the development of more integrative models of healthcare in an effort to deliver patient-centred care. This has occurred alongside a demand from patients for greater information about their conventional care and a rising expectation that complementary therapies will form part of these models of care. Additionally, attitudes among the medical establishment have changed from dismissal of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to demands for greater regulation and evidence of safety and efficacy, in support for further integration (Molassiotis et al 2005). However, this is not the view of all medical practitioners and there is still a concerted on-going campaign against CAM, which Walach (2009) suggests might be due, in part, to the fact that CAM has grown stronger than its proponents realize.

Access to CAM varies within healthcare settings, with the greatest increase being in the field of cancer and palliative care. Corner and Harewood (2004) support this view, suggesting that the use of CAM in this group may be higher than in the general population. When reviewing the literature, a variety of reasons are given for the increasing use of CAM among patients who have cancer. Their use can be placed on a continuum. At one end, their use is a purely pleasurable intervention, while at the other end, they have an enhancing affect on the patient’s quality of life. Their role may be to complement or counteract the side effects of conventional cancer treatments. Cassileth (1998) suggests that CAM has a variety of uses which range from support for patients’ psychological needs, to dissatisfaction with the medical system and/or as a result of a poor relationship with their physicians.

While acknowledging that the use of CAM in healthcare settings, and by the general population, is a way of helping individuals to manage their own self-care and symptom control, it is important to develop models of care which ensure that therapies are safe, appropriate and aim to avoid harm. Tavares (2006) suggests that there are three main elements that need to be considered when integrating complementary therapies into supportive and palliative care and these are: accountability, evidence-based care and the multidisciplinary approach.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Over the past 12 years, government strategies which aim to ensure that quality of care becomes the driving force for the development of health services in England have been central to many reports (DoH 1997, 1998, 2008, NICE 2004). Clinical governance frameworks also provide health service organizations with clear directives on what constitutes commitment to quality and the safeguarding of standards (DoH 1999). However, Peters (2009) suggests that the government is now seeking ways of delivering compassion in the NHS. This follows on from the NHS Review (DoH 2008: 11) in which Lord Darzi states that the NHS ‘provides round the clock, compassionate care and comfort … [that] … should be as safe and effective as possible, with patients treated with compassion, dignity and respect’.

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Evidence-based care has been described by Sackett (1996) as the conscientious, judicious and explicit use of current best evidence when making decisions about the care of individual patients. The need for evidence-based integrative medicine is one of great concern (Dooley 2009). Stone (2002) believes that because of the absence of a credible research base within CAM it has been used as a political stick to hamper attempts at integration. Hypnotherapy practitioners need to integrate the best available evidence into their clinical practice so as to ensure safety and efficacy while ensuring they also do no harm (see Ch. 4).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

Integrated care involves a patient-centred holistic approach, which aims to meet the needs of each individual patient. This approach involves all health professionals and therapists working together, in partnership with patients, to maximize their potential for health and well-being. Tavares (2006) suggests that the delivery of integrated care demands a willingness to collaborate, from both conventional and complementary therapy professionals. Whether hypnotherapy is being offered within healthcare or in a private setting, the therapist should link with the patient’s multidisciplinary team by communicating his/her role in supporting the patient and expected outcomes, as a contribution to the patient’s overall care.

In the past, these interventions may have been offered by a range of separate healthcare professionals, or indeed, interventions such as hypnotherapy were not offered at all. Dixon (2009) comments that what is emerging in general practice is akin to Lord Darzi’s polyclinic plan. The plan suggests that the future GP will offer a much more integrative approach. This will include a whole person approach, for the GP to be an expert in helping patients to help themselves to improve personal health, and to be able to discuss the widest range of safe and effective treatment options, which may include CAM. He further adds that the GPs could have some skills in CAM offering them as part of their work. This view, already practiced by some, would fit in with the integrative model of holistic care (IMHC), which is discussed below.

However, the concept of ‘integrated medicine’ has been criticized by Ernst (2009). He suggests that it is a superfluous term which implies that conventional medicine ignores holistic care. Integrated care is argued to be a ‘whole’ person approach (Dixon 2009) which extends beyond the biomedical model of disease to encompass health and well-being (Rees & Weil 2001). It is a positive approach that considers the causes (e.g. smoking, obesity and lack of exercise) and causes at a personal, social and spiritual level (e.g. stress, low self-esteem and negative messages). Medical care has been criticized as having become so industrialized that it has narrowed its vision to ‘fixing’ the human machine and then treating the side-effects of the technology, rather than being interested in health and healing (Barraclough 2007, WHO 1998). Some patients expect to receive the ‘magic bullet’ which perpetuates the ‘cure me, but don’t ask me to consider changing my lifestyle’. The integrated approach must start before conception and in early childhood to empower communities, families and individuals to engage and take charge of their own health and well-being. For example, in smoking cessation, hypnotherapy cannot stop someone from smoking. However, it can open the door to explore an understanding of why the person smokes and what resources can help them change (see Ch. 10). It is also about working with families, friends, in the wider community and in the workplace.

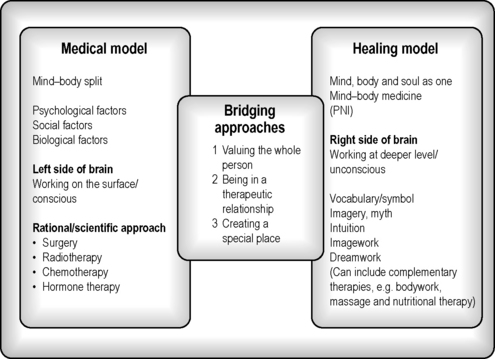

THE INTEGRATIVE MODEL OF HOLISTIC CARE

In order to support patients, hypnotherapists need to have a way of working which helps them to provide safe holistic care. This can include working with an integrative model that is complementary to the patient’s medical care (Cawthorn 2006). The integrative model of holistic care (IMHC) attempts to do this (Fig. 2.1). The model draws on work undertaken in the field of oncology and palliative care by Kearney (1997, 2000) and has been adapted by Cawthorn and Mackereth (2005), Cawthorn (2006) and Molassiotis et al (2005) in an attempt to conceptualize how CAM can be better integrated in different areas of healthcare practice. This approach to care aims to work with the whole person, mind, body and soul, in supporting them through the unique response to their illness. It involves using mind–body medicine, alongside their medical programme, to facilitate personal growth and self-healing.

The IHMC has the following three aspects:

THE HEALING MODEL

The healing aspect of the model is represented on the right hand side of Figure 2.1. Working in this domain lends itself to the use of hypnotherapy as the therapist works with the unconscious, using intuition, symbol, imagery and myth, which can include the use of imagework and dreamwork (Kearney 2000). It also links in with the state of trance which CAM practitioners can access as part of the therapeutic approach. Working in this way links in with research from the emerging field of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI). There is now a substantial amount of evidence into the mind (psychology), the brain (neurology) and the body’s natural defences (immunology), to suggest that the mind and body communicate with each other (Ader 1996) (see Ch. 6). This has been made possible through a rapid advance in the scientific understanding of the immune system over the past 30 years. The concept that every thought, idea and belief is part of the mind–body pathways raises interesting questions into the role of these in maintaining health and fighting disease.

THE MEDICAL MODEL

This is illustrated on the left hand side of Figure 2.1. Kearney (2000) contrasts the approach of the medical model, where the emphasis is placed on the conscious mind. Cunningham (2000) reminds us that the medical model with its mind–body split and care, often ignores the more emotional and existential aspects relating to a diagnosis of cancer or any other life-threatening or life-limiting illness. Medicine has been criticized for its paternalism, which, while well meaning, can be experienced as disempowering, preventing an individual taking responsibility and ownership of their bodies, lives, families and communities (Illich 1979).

The adoption of an integrative model has benefits for both patients and practitioners and many doctors are now looking to offer an integrated approach which recognizes the whole person, not just their medical needs (Dixon 2009). This requires greater communication from all practitioners involved in the patient’s care. A hypnotherapist needs to have an awareness of the diagnosis and treatments which a patient may be undertaking, even though they may not be directly involved with these. Communication can be in many forms, from letters, accessing patient’s notes, being involved in ward rounds, or through adoption of patient-held records.