Ampullectomy and Transduodenal Sphincteroplasty

Bharath D. Nath

Tara S. Kent

DEFINITION

Ampullectomy and transduodenal sphincteroplasty are defined as operative approaches to the resection of lesions of the ampulla of Vater and the palliative or therapeutic reconstruction of the sphincter of Oddi, respectively, performed via a duodenotomy to facilitate exposure of the ampulla within the duodenal lumen. Operation on the sphincter of Oddi consists of reconstruction of the lumen orifices of the pancreatic and/or biliary tree, which may include the following:

Incision of the sphincter alone, without reconstruction (sphincterotomy)

Incision of the sphincter and reapproximation of the duct to the duodenal mucosa (sphincteroplasty)

Incision of the sphincter, division of the septum between the pancreatic and common bile ducts, and their reapproximation with suture (septoplasty)

These operations may be employed for the treatment of benign, functional, and premalignant disorders of the ampulla and sphincter complex. Though both ampullectomy and transduodenal sphincteroplasty may be incorporated as separate components of the same procedure, they effectively serve as the extirpative and the reconstructive phase, respectively, of an operation on the ampulla of Vater.

The standard of care for malignant tumors of the ampulla or periampullary duodenum (as well as the head of the pancreas and distal bile duct) is a pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Ampullectomy is a more limited operation with comparably less morbidity that thus has theoretical benefit for patients with benign or premalignant lesions of the ampulla of Vater.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Transduodenal sphincteroplasty/ampullectomy (TSA) may be considered one of several treatment options for the patient with a mass or functional lesion at the ampulla of Vater. However, the caveat is that TSA is only indicated for a small minority of patients with ampullary lesions and careful consideration of the differential diagnosis is crucial, as it will often lead to other management strategies.

The indications for transduodenal sphincteroplasty include the following:

Impacted common bile stones that are not amenable to extraction by endoscopic means or a “top-down” common bile duct (CBD) exploration

Therapy for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction leading to ongoing injury to the liver and/or pancreas that is refractory to endoscopic management

Management of benign ampullary adenomas

Pancreas divisum

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients may come to clinical attention due to obstructive symptoms of the pancreatic or common bile ducts and may initially present with symptoms of biliary or pancreatic obstruction, such as dark urine, jaundice, steatorrhea, abdominal pain, pruritus, cholangitis, or pancreatitis. Occasionally, melena or iron deficiency anemia may lead to the diagnosis.

The majority of ampullary adenomas are sporadic; however, a significant second group of patients are those with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome.1

Up to 90% of patients with FAP will develop duodenal adenomas, and ampullary adenocarcinoma is the leading cause of death in FAP patients who have undergone prophylactic colectomy.1,2

Whether sporadic or associated with a polyposis syndrome, adenomas at the ampulla are considered precancerous lesions warranting resection.

Various series have documented 25% to greater than 50% of adenomas contain occult malignant foci.1, 2, 3

Adenomas have a 30% transformation rate to carcinoma.4

In several published series, sampling error results in a falsely negative preoperative biopsy in 25% to 30% of cases harboring malignant disease.2,5

As patients with benign ampullary lesions are now often initially managed with endoscopic resection, candidates for surgical ampullectomy comprise a very small group of patients who are neither candidates for endoscopic resection nor for pancreaticoduodenectomy.6 Additionally, patients in whom endoscopic resection has been incomplete or unsuccessful for technically limitations (such as prior Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) may fall into this group.

In one series of 157 patients with ampullary lesions, the presence of jaundice, steatorrhea, dark urine, or pruritus was associated with malignancy, whereas when the presenting symptom was gastrointestinal (GI) bleed, the diagnosis was more commonly benign.7 Notably, patients with obstructive symptoms are highly unlikely to be candidates for ampullectomy because of the association with malignancy.

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) is a well-characterized syndrome that in turn may be due to mechanical causes (e.g., fibrosis) or functional (e.g., dysmotility in the biliary tree, persistent spasm of the sphincter due to neurohormonal dysfunction).

SOD often presents with recurrent biliary-type pain after a cholecystectomy. Other causes of biliary pain, such as retained CBD stone, pancreatitis, and cholangitis, are typically ruled out by extensive workup before the diagnosis of SOD is made.

Additionally, SOD may occur in the setting of a prior Roux-en-Y gastric bypass performed for morbid obesity.8

Patients who have undergone a prior gastric bypass operation or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy for any other indication may have anatomy that renders endoscopic management of ampullary lesions, retained CBD stone, or SOD unfavorable, necessitating a transduodenal approach.

Patients with pancreas divisum are thought to have pancreatitis secondary to minor papillary insufficiency. This group of patients should initially be managed conservatively, and replacement of pancreatic enzymes alone may decrease symptoms. Endoscopic therapy with minor papillotomy or surgical minor papillary sphincteroplasty is the next option.9

A final category of patients who may require surgical intervention on the ampulla include those who have sustained a posterior duodenal perforation as a complication of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography. Most often, these injuries should be managed nonoperatively; however, when the injury is immediately recognized, emergent transduodenal sphincteroplasty may be considered in carefully selected patients.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

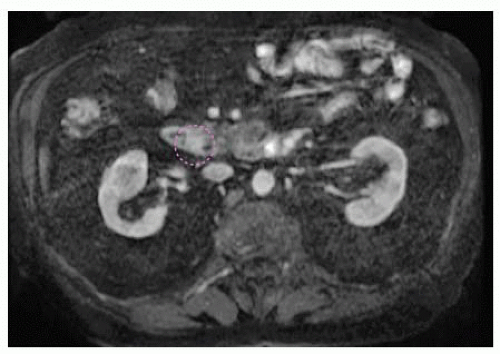

Noninvasive imaging modalities may include magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and computed tomography (CT) with pancreatobiliary contrast protocols (FIG 1).

Invasive modalities include endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERCP) or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and are part of the initial workup for lesions of the ampulla.

Imaging modalities can provide information on extent of local disease including depth of invasion, if applicable. CT scans are the usual initial diagnostic imaging studies performed, due to ready availability and ease of interpretation.

CT scan has use for the detection of nodal disease or distant metastases, whereas EUS has a great deal of use in the detection of depth of invasion of ampullary adenoma and hence has a role in the workup of disease amenable to local resection (FIG 2). This point is not without controversy, as others have argued that CT scan is not superior to EUS in terms of nodal staging.

When stricture at the ampulla is suspected, ERCP can be used to clarify the extension of the stricture into the pancreatic parenchyma or the distal CBD; this information is critical for operative planning.

FIG 1 • MRCP image demonstrating a 1.3-cm adenoma at the ampulla of Vater. The ampullary adenoma is outlined in a dashed purple line in this image.

For strictures that extend beyond the ampulla itself, the operation of choice would be a pancreaticoduodenectomy or CBD reconstruction, that is, hepaticojejunostomy depending on the etiology.

ERCP, hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, and MRCP with secretin stimulation or sphincter manometry may be used to make the diagnosis of SOD.

Patients with delayed excretion of contrast after ERCP (>45 minutes), CBD dilatation greater than 1.2 cm, and elevated alkaline phosphatase or serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) (greater than two times the upper limit of normal) have excellent response to endoscopic sphincterotomy alone without other diagnostic maneuvers.

Patients who meet some but not all of these criteria benefit from further diagnostic testing with manometry, and those patients in whom manometry is abnormal may benefit from sphincterotomy.

Patient with biliary pain but without any of the aforementioned abnormalities may undergo manometry but have generally lower rates of success following sphincterotomy even in the presence of abnormal manometry.

Although this has not been validated prospectively, one small study suggested that HIDA scan with morphine as an adjunct has the advantage of a noninvasive test that, when positive, correlates well with a positive surgical outcome.10

MRCP with secretin stimulation is another modality that has been used to demonstrate SOD dysfunction in patients with prior Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity.8

Sphincter manometry is performed via a miniaturized pressure catheter that is placed in the sphincter of Oddi using a side-viewing endoscope. Four categories of manometric abnormalities are defined and include the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree