AMBULATORY CARE

Megan Kaun, PharmD, BCPS, BCACP, and Michelle Serres, PharmD, BC-ADM, BCACP

CASE

K.C. is a student preparing to start her ambulatory care rotation in an internal medicine outpatient clinic. She is asked to work up the patients that will be seen that day using the chart in the electronic medical record. She writes down most of the information for each patient using a form to organize the information. She feels confident and is able to present the patient information to the preceptor before the patient arrives. The preceptor notifies K.C. that he is running behind and would like her to begin talking with the first patient about his medications and measure his blood pressure. K.C. suddenly becomes very nervous and is uncertain how to talk with the patient or what to discuss.

WHY IT’S ESSENTIAL

Ambulatory care rotations are one of the four rotation types required by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). Ambulatory care rotations may include a variety of experiences and settings, but all have the common goal of direct patient care in an outpatient environment. Common examples of ambulatory care rotations include physician’s offices, anticoagulation clinics, and medication therapy management (MTM) clinics. Ambulatory care rotations may also take place in community pharmacy settings. In this situation, the focus of the rotation is not the dispensing services but rather the clinical interventions made. Skills developed during an ambulatory care rotation emphasize drug knowledge, pharmacotherapeutic plan development, and communication skills with patients and other healthcare team members.

ARRIVING PREPARED

As with all rotations, the preceptor should be contacted well in advance of the rotation to inquire about expectations and preparations. Ambulatory care settings may vary greatly from one rotation to the next, so it is advisable to not make assumptions about how to prepare, what to bring, hours, and expectations of the rotation.

You should ask the preceptor the following questions in your initial communication:

- When and where should I arrive on the first day?

- Are there any restrictions regarding parking?

- How can I best prepare for this rotation?

- Is there anything specific you would like me to bring?

In addition, it is safe to assume the following apply to all ambulatory care rotations:

- Dress professionally, wearing a white coat and nametag identification.

- Bring your favorite drug information reference.

- Bring a notebook, pens, and calculator.

- Bring your lunch on the first day, as you may not have options to obtain lunch throughout the day.

- Review guidelines or references specific to that rotation (for examples, see the Suggested Reading section at the end of this chapter).

Ambulatory care has a primary focus on patient interactions. On this type of rotation, you will be expected to communicate directly with patients, either in person or on the phone. This process can be quite intimidating the first time you try it. You will encounter patients with diverse backgrounds, diverse personalities, and differing levels of health literacy. You must enter the rotation with an open mind and expect that you will need to call on your highest level of communication skills.

QUICK TIP

If patient communication is new or uncomfortable to you, consider practicing with friends or family as if they were your patients. Ask them for feedback on how they felt you were able to ask and answer different questions and provide information.

Depending on the type of rotation, you will likely be asked to work up the patient prior to his or her arrival. Having a systematic process for this workup will help efficiency and accuracy. Areas to consider when working up a patient of any type include the following:

- Is this a new or returning patient to pharmacy services?

Identify what service the referring practitioner would like you to provide, such as

Identify what service the referring practitioner would like you to provide, such as

- Diabetes management

- Medication reconciliation

- Hypertension management

If returning, what was accomplished at the last visit or interaction?

If returning, what was accomplished at the last visit or interaction?

If new, what was discussed at the last practitioner appointment or what led to the referral?

If new, what was discussed at the last practitioner appointment or what led to the referral?

- Gather basic information, such as

Patient age, height, and weight

Patient age, height, and weight

Past medical history

Past medical history

Current medication list

Current medication list

Applicable laboratory work (and dates of laboratory work)

Applicable laboratory work (and dates of laboratory work)

- Review common medication administration techniques you may need to teach to patients, such as

Insulin or low-molecular-weight heparin injection technique

Insulin or low-molecular-weight heparin injection technique

Inhaler use

Inhaler use

Glucometer use

Glucometer use

Home blood pressure monitor use

Home blood pressure monitor use

- Identify information important to standards of care

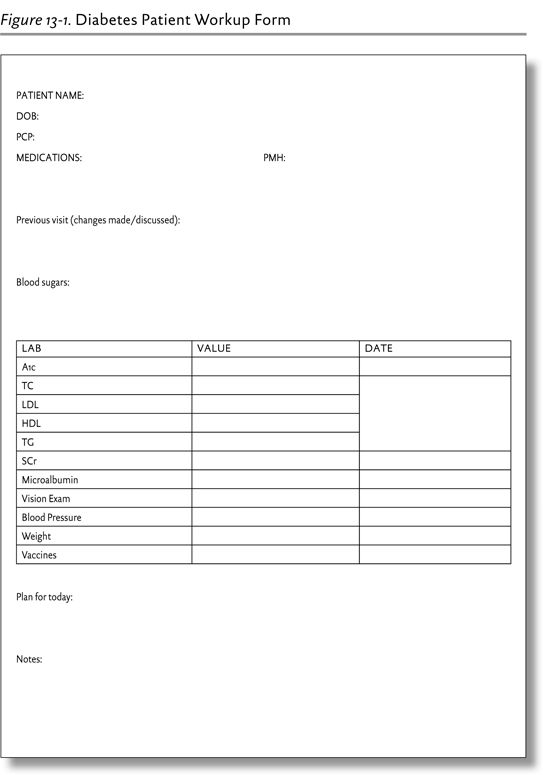

Having a patient workup form can be very helpful in this process. Figure 13-1 is an example of a workup form that could be used in a diabetes clinic. Your preceptor may provide a workup form for his or her specific clinic, or you may develop a form of your own.

CASE QUESTION

K.C. was very uncomfortable for her first direct patient care experience. Name one technique that she could have used before seeing her first patient that may have improved her comfort level.

As previously mentioned, each ambulatory care rotation is quite different. You should prepare accordingly for each specialty type, including reviewing class notes, textbook chapters, and guidelines for the most common disease states you expect to encounter. Some settings may be family based or internal medicine based, whereas others specialize in one particular disease state. The family medicine-based specialty areas you may encounter include diabetes, anticoagulation, lipids, hypertension, and smoking cessation. In an internal medicine or family medicine setting, you may be able to focus on the following disease states:

- Outpatient infectious disease

Urinary tract infections

Urinary tract infections

Upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, and otitis media

Upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, and otitis media

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia

- Thyroid dysfunction

- Depression and anxiety

- Pain management

- Asthma

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Tobacco addiction/smoking cessation

- Anticoagulation

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

For a specialized clinic, you should read textbook chapters, notes, and guidelines for that particular disease state. Guidelines are listed in the Suggested Reading section at the end of this chapter.

A TYPICAL DAY

A typical day in an ambulatory care rotation will vary greatly depending on the specific rotation you are completing. At some sites you may see patients every day of the week, whereas at others you may see patients less frequently but have more time to perform patient workups, documentation, and presentations or projects. Below is an example of a typical day you may face when on this type of rotation.

The morning may start with working up patients prior to their arrival. At some sites, you may do this ahead of time for all patients, whereas at others you may work up each patient just before he or she arrives. Usually your preceptor will have you verbally present the patient’s workup at some point prior to meeting with or calling to speak to the patient. Successful presentation of a patient should usually include the following:

- Patient’s name

- Age

- Reason for appointment

- Pertinent medical history

- Pertinent social history

- Complete medication list

- Actions completed at last patient visit

- Any recommendations you have regarding the patient’s therapy

Additionally, your preceptor may want you to come up with a plan for the appointment. For this, you should discuss the areas you think need to be addressed with the patient and all of the points you would like to see covered. See Chapter 6 for a full discussion of case presentations.

After presenting the case, it is time to meet with the patient. At some sites, this may be face to face, whereas at others, it may be over the phone. The purpose of the visit is both to gather additional information from the patient and to provide the patient with information. Exactly what is discussed and how it is done varies among sites. Typically, you or your preceptor will begin by asking questions to gather information and create a plan that will be delivered to the patient. It is important to keep accurate notes of what patients and practitioners say during the visit so that it can be included in the documentation.

After the patient’s appointment concludes, it is time to document. Documentation is vital to create continuity of patient care and also may be required to justify pharmacist billing. Although this is most commonly completed using some type of SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, and plan) note, documentation can take many forms. Typically, you will write up your note and the preceptor will review it. Once finalized, the documentation is usually added to the patient’s record.

In addition to the core areas of direct patient care just discussed, your day may also include a variety of activities, including topic discussions, responses to drug information questions, creating patient or healthcare team education materials, presentations, or spending time with other members of the healthcare team, such as physicians, nurses, social workers, educators, and psychologists.

IDENTIFYING DRUG-RELATED PROBLEMS

Drug-related problems (DRPs) are the undesirable events that occur outside of the desirable pharmacological response to a medication (or the potential for such events). Identification of DRPs is an essential skill on most rotation types and is put to particularly good use at ambulatory care sites. Identifying DRPs is a challenging skill that takes many years to refine. Having a systematic process will be very helpful, especially early in your career. DRPs are traditionally broken down into nine major categories (see Tables 13-1 and 13-2). Using these lists will help you to maximize your ability to properly identify DRPs when applied consistently to each patient situation. All of these DRPs are used throughout the ambulatory care setting and must be evaluated for each patient seen.

TABLE 13-1. TYPES OF DRUG-RELATED PROBLEMS

TYPE OF DRP | EXAMPLE |

A problem of the patient is not being treated or is not maximally being treated. a. Missed medical problem b. Suboptimal therapeutic approach c. Suboptimal drug selection d. Medication duplication | Hyperlipidemia is noted by lab data, but the patient is not receiving a lipid-lowering drug. A patient with heart failure is taking furosemide and digoxin but not an ACE-I. A patient is taking HTN medications and BP is better than before but still elevated, yet no additional adjustment in therapy is being made. A patient with diabetes and HTN is taking a beta-blocker instead of an ACE-I. A patient with normal renal function is receiving furosemide for HTN rather than HCTZ. A patient with HTN is taking HCTZ and chlorthalidone. |

A drug a patient is receiving is a. Not indicated b. Contraindicated | A patient diagnosed with anemia due to chronic illness is being treated with iron sulfate. A patient is receiving digoxin for no apparent reason. A patient with heart failure is prescribed cilostazol. |